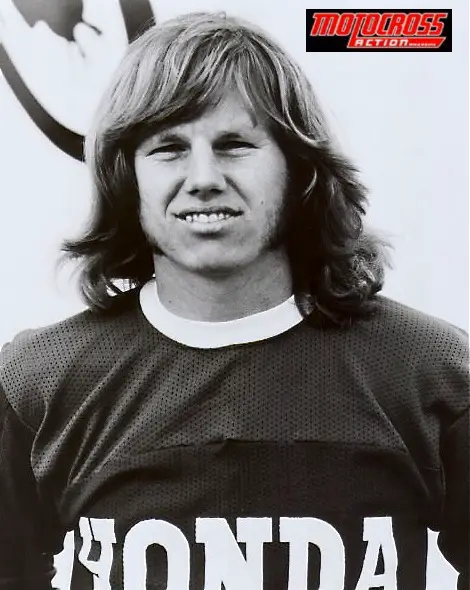

GODSPEED! RICH EIERSTEDT (1954-2010):

By Jody Weisel

It isn’t always easy being a friend and over my 35-year-friendship with Rich Eierstedt I don’t think I ever fully understood him. Maybe I wasn’t equipped to handle the devils that seemed to beset this wonderfully nice and caring person.

My first experiences with Rich Eierstedt (pronounced Air-Stett) were way back in the day. Rich had been hand-picked from the pack at Saddleback Park to join Marty Smith, Bruce McDougal, Gaylon Mosier, Rex Staten, Marty Tripes, Gary Jones and DeWayne Jones on the first official Honda motocross team. He was one of the first generation of rock star motocross riders and was perfectly suited to the role. Rich was handsome, always smiling and had an effortless riding style that made you think he wasn’t going fast—but he was.

Rich was what the motocross explosion of the 1970s was all about. His first bike was a Rupp minibike in 1964. He went through a series of roach bikes that he either bought with part-time job money or his parents got for him. He started racing on a Greeves Challenger that had been Jim Wilson’s practice bike. He did so well that he was moved to the Pro class within his first five races. The crux moment for Rich was when he won a Penton 125 as a prize at a race series. He sold the Penton and used the money to buy a Maico. The rest is history. Eierstedt and close friend Gaylon Mosier owned SoCal on those Maicos. They did so well that both of them got the call to join Team Honda in 1973.

I always used to kid Rich about his Norwegian last name and given that my German last name is equally hard to pronounce…he would always take great pleasure in saying that his name was just like the kid’s song “Old MacDonald’s Farm.” Then, he would sing, “Ee-i-ee-i-oh!” No one could forget after that to spell Rich’s last name you started with an e, then an i and then another e.

During his career on Team Honda, Team Bultaco, Team Harley-Davidson and Team Can-Am, Rich won two 500cc Supercrosses (Houston and Pontiac in 1976), finished third in the 1975 AMA Supercross Championship and had top ten finishes in the AMA Nationals in 1976 (Honda), 1977 (Bultaco) and 1978 (Can-Am)?and the Supercross series in 1975 and 1978. Rich was most famous as a Trans-AMA Support class hired gun. He would go on win the 250cc Trans-AMA Support class in 1973 and 1976.

Then, mysteriously, Rich walked away from Team Can-Am midway through second half of the 1979 season. Rich is one of only a handful of pro racers to give up a factory ride in the middle of a race series. Rich had a secret…not a secret from his family or soon-to-be ex-wife, but a secret from the motocross world—he was an alcoholic.

Rich’s personal problems off the track had sapped his energy for professional motocross racing. Rich was mostly gone from the motocross scene for the next 17 years. We kept in touch, but keeping in touch with Rich was always a touch-and-go affair. When Rich drank, he gave it the same effort that he did on the race track?100 percent. And when he drank he was moody, difficult and totally obsessed. It was sad to see and I am ashamed to say that except for the occasional phone call from 1979 until 1994, I considered Rich Eierstedt to be a lost cause.

Amazingly in 1994, right after Rich had turned 40-years-old, he called and we talked for a long time. My advice was far from sage, but I told him that the best times of his life were on a motorcycle…and that if he wanted to race I would give him bikes, parts, gear and my full support. He surprised me by showing up at the Mammoth Mountain Vet weekend on a borrowed bike and winning. From that moment on, through a serious of ups-and-downs, I tried to keep Rich on the straight and narrow. I’m not an alcohol therapist, and, in truth, Rich didn’t need one because in 1994, when he made his return to the sport that he loved as a child, he was working as a counselor at an alcohol treatment facility. Rich knew alcoholism from both sides. I wanted to help my old friend in the only way I knew?the motocross way. I told him that as long as he called me every Friday and showed up to race on the weekends I would do everything I could to give him an outlet to burn off energy and exorcise the demons.

For 12 years, MXA supported Rich Eierstedt’s racing. We used him as a test rider and included him in on every thing we did and every race we went to (we even took him to Sweden for the Swedish-American Vet Series with Thorlief Hansen, Gary Jones, Lars Larsson and Alan Olson). Rich was still immensely talented and just as friendly, smiling and easy going as when he was 17. But he could also be petulant, moody, dark and paranoid. For such and easy-going guy, he was incredibly hard on himself. If he didn’t get the holeshot, he was angry. If he got second overall, he was livid. If he had problems on the track, it was always somebody else’s fault. Rich was, for the whole 35 years that I knew him, a confusing juxtaposition of man/child.

But, through it all, he was still an alcoholic?whether he drank or not..he knew that he would always be haunted by a desire to bury his pain. Over time, at almost regular intervals, Rich fell off the wagon. Often he had reasons that were understandable, like the suicide of this father and later the death of his mother. And sometimes, he would, for no obvious reason, just turn into a liquor store parking lot and buy a bottle.

I could always tell when Rich was drinking because he wouldn’t call me on Friday. Weeks would pass and then finally the phone would ring and it would be Rich. He would be apologetic, remorseful and claim that he was never going to take another drink. And he was true to his word (for the next eight or nine months). When he came to the track for the first time after a bender, he looked like a hollow, weak and used-up person. It was frightful what drink does to the human body and spirit. It wasn’t my job to judge his actions, but to support him in the one activity that he loved. I was mystified why the friendship of an active group of racers and an arena to display his ample talents wasn’t enough for Rich, but it wasn’t. And, although it is hard to put these events out of my mind, I have always preferred to remember the good times that Rich and I had.

The last time Rich raced was a very weird experience for me. I came in from the first moto and Rich, who had been next to me on the starting line, was gone. He had pulled off the track in the middle of the race, got undressed and drove away (just like he had in 1979). I asked his friend Brian Martin, who had known Rich since high school, where Rich went. Brian said, “He pulled off the track because he was running third and claimed that he wasn’t going to ride like that. He got in his truck and stormed off.”

That was the end of it. Oh, I’d got an occasional email from Rich. I always gave him tickets for the AMA Nationals and the USGP and even saw him once this past year when he rode out to the track on his Harley to watch us race.

I waited for that Friday phone call for the last four years. it never came. Instead, the phone rang this morning and it was Phil Alderton. Phil was in Ohio, where he is busy preparing his Honda of Troy race team for the coming season, but had been Rich’s roommate for the last two years. Phil said, “I have some bad news to tell you. Rich died last night. His brother Jeff found him on the couch this morning in the same position that he left him last night. His heart must have given out.”

With that news, my heart has given out also.

During his time as an MXA test rider, Rich raced everything from an XR650 to a YZ125 (43).

JODY’S NOTE: For those who believe that my memorial to Rich Eierstedt is too harsh. I would like to include a story that Rich wrote to me in October of 1995. I questioned him on whether he wanted to reveal to the public, that saw him as a motocross hero, that he was an alcoholic. Rich was emphatic that I not only I read his story, but that I get it published in Motocross Journal. I did…and Rich was very proud of it because he felt that telling the story of the effects of his alcoholism just might help another person avoid what he had gone through. I am positive that Rich would feel even more so after his death. Here is Rich’s story in his own word.

THE TRUE STORY OF RICH EIERSTEDT BY RICH EIERSTEDT: THE 17 YEARS THAT GOT AWAY

“The drive was half over before I realized it. It was the summer of 1994 and I was headed up Highway 395 towards Mammoth Mountain. It was hard for me to believe that it had been 17 hears since I had raced at the Mammoth Mountain Motocross.

“In a way, it had been the beginning of my decline as a motocross racer (and as a person). In 1977 I went up there to race, but rather than hang out with my buddies, I decided to stay in my motel room, watch TV and drink. I was bored, and watching The Love Boat, Fantasy Island and the bottom of a pint of brandy seemed like a good way to pass the time. By the time practice rolled around the next morning, I was hung over and fuzzy. Somehow I won the first moto, even though I got a flat tire late in the race. My chances of winning overall were ruined in a first-turn pile-up at the start of the second moto. Working my way back up towards the front was good enough for me to get fourth overall and make enough money to pay for the week I had spent on the mountain. Alcohol dehydrates the body, but I had learned not only to function that way, but also to like the empty feeling it gave you. That night I got drunk again.

“I woke up the next morning in jail in the town of Bishop, California. I don’t know how I got there.

“So, as I drove up to Mammoth Mountain 17 years later (in 1994), these thoughts came flowing back. I was now 40 years old and I had been sober for two years. You do the math. To me, my life was just starting. I felt like I was 18 years old again and had something to prove.

“For many people, of which I am one, alcohol is like climbing into a boxing ring with a smarter, stronger, younger opponent. You survive the first few rounds, occasionally getting in a few licks, and your ego tells you that you can go another round with the bottle. You keep answering the next bell and the next. You are losing. Losing big. But it doesn’t matter.

“Alcohol beat me. I kept on losing. The first things I lost were the material things I had gained from being a factory rider: First, the condo, then the apartments and finally the tax shelters. It wasn’t long before it was all gone: the job, the wife and lastly, the home. I had gone from the pinnacle of motocross to the bottom of the social ladder. I had hit rock bottom. At least I thought I was on the bottom; I wasn’t even close.

“In October 1992, I lost my freedom! Four months in jail. After having already spent 30 days in a hospital and a month at the Betty Ford Clinic, I believed I was immune to being confined. I was wrong! It took jail for this hard-headed Norwegian motorcycle racer to see the light.

“Jail broke me! It was the worst thing that ever happened to me, but it was there I found the best thing to come along in my life: God.

“I’m sure you’ve all read books or seen movies about people finding God in prison. Whether it was Malcolm X, Charles Colson or the Birdman of Alcatraz, I always felt that finding religion in jail was just a ploy criminals used to trick society and the justice system into believing that they were rehabilitated. I was wrong. While lying in my cell reading a novel one day, a feeling came over me that I cannot describe—except that I knew that from that moment everything was going to be okay.

“A month later I got out of jail. I was 38 years old, living with my parents and on welfare. It was not a pretty sight. I had nowhere to go but up. At five foot ten inches and 195 pounds, I fell back on what I knew had worked in my youth. I decided to get back in shape. Since my driver’s license had been taken away by the California Department of Motor Vehicles, I dug an old ten-speed out of my garage and started riding. I couldn’t afford a gym so I did pushups and sit-ups. I started to feel healthy. The effects of 15 years of alcohol were finally beginning to leave my cells.

“All this time I had a recurring dream about the first turn at Mammoth Mountain; high on a pine-covered hill, with the pits in the background way below me, I saw myself in first place. It wasn’t a dream that I was in a position to do anything about, and when I finally felt that I was fit enough to ride a motorcycle again, I didn’t have one. Back in 1979 I had walked away from the sport. I had a factory Can-Am ride, all the bikes I wanted, a box van, a mechanic and the applause of thousands of cheering fans. I took it all for granted. So, in 1994 I called my former factory mechanic and friend Wayne Mooridian, who owns a hop-up company called P.E.P., and asked him if he could lend me a motorcycle. Wayne had one. It was nine-years-old and hadn’t been raced in that many years. It looked like a new bike to me! Mammoth was coming up so I took the old bike out to Perris Raceway and won the first three races I entered. At Perris I ran into Team Kawasaki Manager Roy Turner who used to be my mechanic at Team Honda back in the 1970s. Roy offered to lend me a bike for Mammoth, even after I explained to him where I’d been for the last 15 years. Next, I called John Gregory at JT Racing. He set me up with new riding gear. I couldn’t believe it, all these guys that I had left behind on my trip to the depths were there for me when I returned to the surface.

“My quest was the Over-40 Mammoth Championships. Much like the PGA Senior Golf Tour, the International Old Timers’ Club hosts a World Championship race at Mammoth each year. For me it would be a homecoming—back to the place where I had suffered my biggest defeat 17 years earlier. I had gotten my driver’s license back and my dad gave me an old Ford Courier pickup truck. I loaded my new Kawasaki and riding gear and headed up Highway 395. It was a 350-mile drive with a big hill at the end—the little truck didn’t make it! It took a day to get the Ford fixed and I missed the last practice day before the race. As my little truck and I chugged into the pits and weaved our way through the box vans, motorhomes and big rigs, I was pretty sure that I was the only rider there on welfare!

“There were four motos over the two-day Over-40 Mammoth Championships. By the end of the weekend, I had won three motos and placed second in the other and was awarded the Old Timer’s World Championship. What I remember most was that as I made that turn high on a pine-covered hill with the pits in the background—I was in first place.

“I am one lucky alcoholic!”

Comments are closed.