HOW TO WIN A 24-HOUR ENDURANCE RACE BY JOSH MOSIMAN

HOW TO WIN A 24-HOUR ENDURANCE RACE BY JOSH MOSIMAN

The word “team” is defined as, “A group of players forming one side in a competitive game or sport.” The 3 Brothers-sponsored 24-Hours of Glen Helen endurance race is a team event with classes for all ages and skill levels, but it mostly consists of big-bike riders. The Amateur classes allow for six riders and two bikes per team (one bike to be in impound at all times). For the Pro class, only four riders and one bike are allowed for the entire 24-hour race. The basic strategy in the Pro class is to build a bike capable of surviving 24 continuous hours of abuse, get four riders who ride fast enough to have a shot at winning but are smart enough to conserve the bike without wrecking it, and to find a pit crew willing to work around the clock to see the wild adventure through.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT RIDERS FOR SUCH A GRUELING UNDERTAKING WAS IMPORTANT. I WANTED RIDERS WHO WERE FAST BUT ALSO SMART. OBVIOUSLY, ZAC COMMANS HAD BEEN MY FIRST CHOICE, WHICH WAS GREAT BECAUSE HE GOT MITCH PAYTON ON BOARD.

I wanted to race the 24-Hours of Glen Helen and had enlisted my friend Zac Commans to race the 10-Hours of Glen Helen with me earlier in the year as an exploratory fact-finding mission. We enjoyed it and decided to tackle the much longer 24-Hours of Glen Helen. Originally, when the plan for this race was forming, my friend Zac Commans had mentioned that Mitch Payton might want to be a part of the effort. Mitch is a very busy man, but Zac thought that he could help us with advice, suspension and maybe an exhaust system. But, Mitch was in for a lot more than that. Mitch bought us a brand-new 2020 Honda CRF450X. He commissioned Jim “Bones” Bacon, who consults with Pro Circuit, to give us the special off-road suspension settings that he developed with the Johnny Campbell Racing (JCR) Honda team and Pro Circuit’s Luke Boyk. Mitch then convinced his main R&D technician and former Factory Honda mechanic for Justin Barcia, Mike Tomlin (better known as “Schnikey”), to be our head mechanic and spend lots of time after hours at the Pro Circuit shop building the bike.

Mitch still wasn’t done yet. Mitch got his friend Johnny Campbell, owner of the JCR Honda off-road team and an 11-time Baja 1000 Champion, to give us advice on long-distance cross-country racing. After all, Johnny developed the CRF450X model with Honda, and he knows it better than anyone. Mitch also bought helmet lights for the riders and the headlights for the bike, and he spent late nights at the shop going above and beyond for our team to ensure we were as prepared as possible.

Mitch and Zac Commans have known each other since Zac was a young minicycle rider training with Adam Cianciarulo and his dad Alan. Similar to me, Zac raced AMA Pro for a few years until deciding to forgo the 2018 season and go to college instead. Mitch and Zac are still good friends, and Mitch was excited to be part of the team when Zac told him that he’d be shaking off the rust for the 24-Hours of Glen Helen.

What most motocross fans don’t know about Mitch Payton is that he has a soft spot for this race and for off-road racing in general. Why? Mitch grew up as a desert racer and has put teams together to race the 24 Hours multiple times. Surprisingly, even with great riders on its team, Pro Circuit has never won the race before.

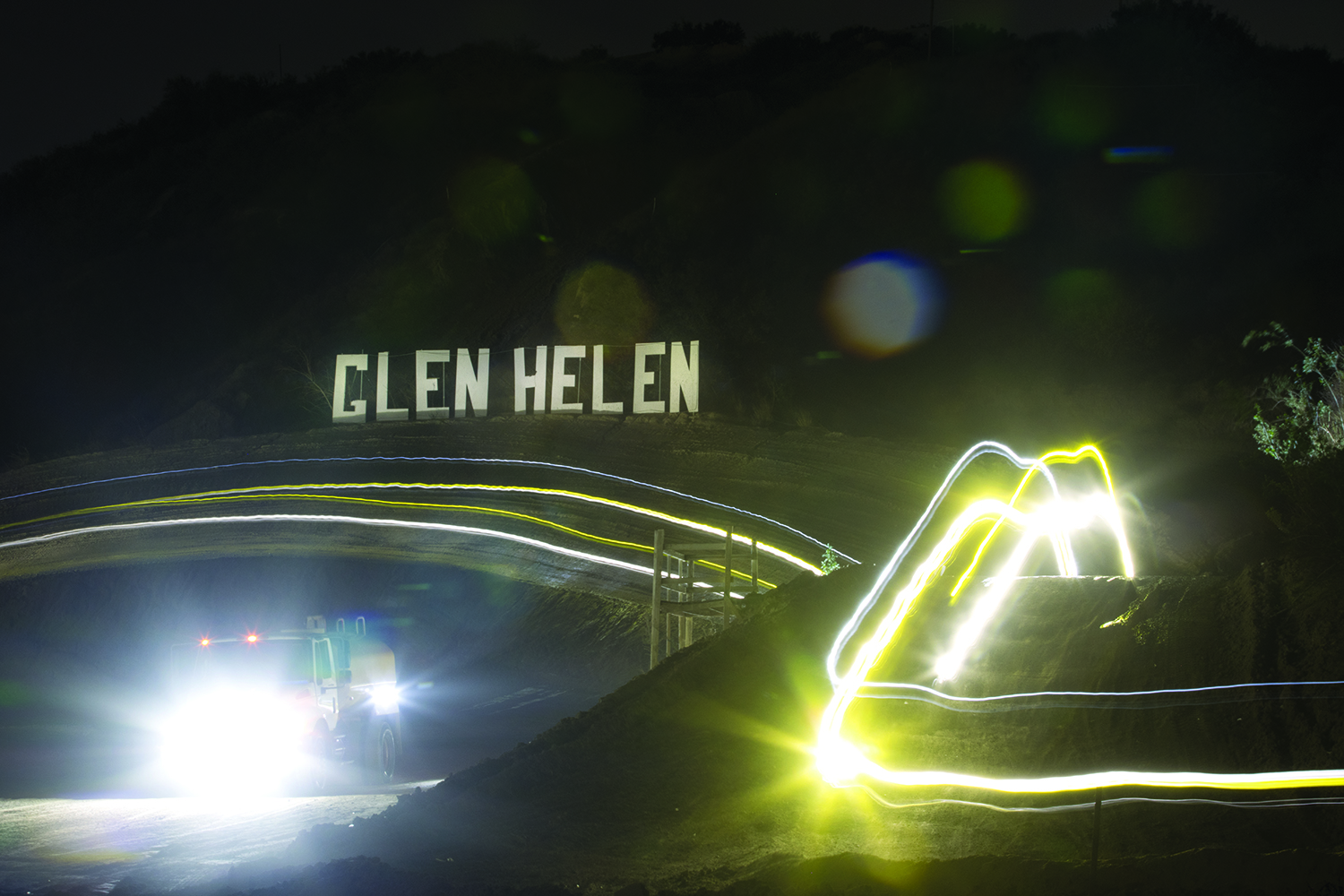

THE 24-HOUR COURSE WAS LAID OUT ON PORTIONS OF GLEN HELEN THAT I HAD NEVER SEEN BEFORE—AND I TEST AND RACE THERE A COUPLE TIMES A WEEK.

As for the rest of the crew, I already mentioned that Bones dialed in our suspension, but I didn’t tell you that he was actually the crew chief for the team and split his time between Pro Circuit’s race shop and Glen Helen Raceway testing the bike with us. Bones and Mitch were both vocal in our late-night strategy meetings at the shop and developed a checklist of spare parts and accessories we would need for the race and for our pit area. Beyond Mitch and Bones, we had Schnikey as our head mechanic. My former AMA National race mechanic, Averi “Avo” Lison, took a week off work to fly down from Wyoming to help. Another former factory Honda mechanic, Jason “Gothic Jay” Haines, joined the pit crew as well.

Choosing the right riders for such a grueling undertaking was important. I wanted riders who were fast but also smart. Obviously, Zac Commans had been my first choice, which was great because he got Mitch Payton on board. Carlen Gardner was my next choice, because he has raced the AMA Supercross series for the BWR Honda team and understands how a team works. The fourth choice was Preston Campbell. You may have never heard of him, but he is a successful Hare and Hound off-road racer and brings with him a wealth of off-road racing know how. And, as the son of Johnny Campbell, he wanted very much to win the 24-Hours of Glen Helen to uphold family honor.

The decision to race a Honda came as a result of Mitch’s friendship with Johnny Campbell and Pro Circuit’s support of his factory JCR Honda team. Pro Circuit already does the suspension and engines for Johnny’s team, and Mitch was excited to build his own bike from the ground up. The CRF450X version was chosen instead of the CRF450 because it’s more of an off-road machine. It has a six-speed transmission, more flexible chassis and stronger electrical output for the headlight. If we were racing a Grand Prix-style event with a shorter duration, we would have chosen the CRF450 because it produces more power out of the box and is more “racy” with a stiffer chassis and sharper handling. But, with 24 hours of riding to do, we chose the bike that offered the most forgiving ride—something I appreciated at 5:00 a.m. Sunday morning when I put in my fifth stint.

When it came to preparing the bike for the race, we had a wealth of knowledge to pull from. Johnny Campbell is a living legend in off-road racing, and his son Preston really stepped up to the plate and used his personal racing experience and knowledge of the Honda to help us dial it in. Preston has grown up around his dad, and he has been part of a lot of cool projects, so for this race, we relied heavily on Preston to help us prepare and get through the 24 hours while his dad was getting ready to race an off-road truck at the Baja 1000.

With just under two weeks to go, we got the team together at the Pro Circuit shop to go over the strategy, combine our resources and talk over any last-minute details that we needed to tighten up before the big race. We met at Pro Circuit after hours. Mitch, Bones and Schnikey were there. Zac came straight from his job in Riverside. I came straight from Jody’s house after spending the day testing at Glen Helen. Preston came after spending the day working for the Honda media department at Cahuilla Creek Motocross Park, and Carlen drove for three and a half hours to get from his hometown of Paso Robles to the Pro Circuit shop in Corona.

Sitting down in the meeting room at Pro Circuit and listening to Mitch and Bones talk over the details, I came to understand more about my friend Zac Commans. Zac has spent a lot of time with Mitch and Bones over the years, racing and testing bikes for Pro Circuit. Undoubtedly, their personalities have rubbed off on Zac, and now I have more perspective on him. Zac is analytical, and he wanted to have every detail marked down on his notepad. Mitch and Bones were similar and seemed to enjoy plotting each aspect of how the pit area would operate, how many spare parts we would need and who would do what when the time came for action.

The 24-Hour course was laid out on portions of Glen Helen that I had never seen before—and I test and race there a couple times a week. We utilized everything the facility had to offer—the AMA National track, the mountain ridges, the ultra-tight single-track, the dry and rocky creek beds, the REM track, portions of the Stadiumcross track, the Lucas Oil off-road truck track and some really tough sand washes. To best prepare the bike for what we would encounter, Mitch ported the head with the same specs he uses on the CRF450. We elected to run a modified CRF450 camshaft with the matching springs and finger-followers. We used one of Colton Udall’s Champion Adventures smog-pump block-off kits to shave 2 pounds of California emissions equipment off. And, of course, we used a Pro Circuit Ti-6 Pro exhaust to finish boosting the power. Mitch kept the compression ratio at the stock specs because he wanted the mods to be simple and the loads on the engine light. The CRF450X starts out down on power when compared to the CRF450, so he recouped some of the ponies, but he didn’t want to sacrifice reliability.

WHEN FRIDAY EVENING CAME, I WAS WORN OUT. I TOLD MY TEAMMATES THAT I FELT LIKE I HAD ALREADY RACED 24 HOURS. I WASN’T THE ONLY ONE FEELING THIS WAY.

Joe Lloyd from the JCR Speed Shop removed the stock headlight, built a custom bracket and installed a Baja Designs XL80 light into a custom mount he built to bring the light as close to the steering stem as possible. His mount helped centralize mass and limit the amount of weight swinging with the handlebar. Joe also removed the stock CRF450X ECU to perform electrical surgery so he could install a CRF450 black box with the Johnny Campbell spec settings that Preston has been racing with at the National Hare and Hound events. Both of these services are available from the JCR Speed Shop.

Besides the Pro Circuit and JCR mods, we trusted Twin Air filters to keep dirt and dust out of the engine. Many off-road riders use stock air filters for endurance races because they’re thicker. They restrict airflow but block more dirt; however, Mitch and Schnikey chose to use Twin Air filters instead, and we just made sure they had plenty of filter oil (and Mitch’s game plan was to the change air filters every four hours). Next, we used a full Hinson billetproof clutch that included the clutch cover, basket, inner hub, pressure plate, clutch plates and springs. We bolted on a Scotts steering stabilizer with a BRP top triple clamp, and an Anti-Gravity 8-cell AG-801 battery to make sure the electric starter and our lights kept working day and night. We installed a Works Connection clutch assembly, oversized IMS gas tank, and a BRP chain guide and rear brake rotor guard. We switched to a heavy-duty D.I.D rivet link chain, Renthal handlebars, Dunlop MX52 tires with bib mousses, Acerbis hand guards and the stock Honda skid plate. We ran pump gas, because Mitch hadn’t raised the compression.

Being the world-class mechanic he is, Schnikey had a few tricks up his sleeve to add some durability to the bike. To protect against roost, trees, bushes and crash damage, Schnikey doubled up the stock radiator hoses, added a brake snake and helped Norm Bigelow weld some gussets to the chain guide mount to increase its strength. He wire-tied the nut at the bottom of the clutch cable, wire-tied the front brake rotor guard, secured the radiator cap with a pin and, while he was at it, polished the axles to make sure they wouldn’t hang up when changing the wheels. He also chamfered the stock front and rear brake pads to speed up the process of changing wheels. Next, Schnikey added plastic screens onto the radiator guards to keep sticks, rocks, dirt and mud from puncturing or clogging up the radiators, and he added another screen on the backside of the stock front number plate where the stock headlight would typically be to protect the wires that were exposed for the first part of the race.

My favorite trick was when Schnikey drilled tiny holes in the tabs that held on the radiator guards and pushed small pins through the holes to keep them secure. This way, if the radiator shrouds ripped off, our radiator guards would still be there to protect the radiator. Last, Preston Campbell spray-painted the front fender with a matte finish black, and the front fender graphics from Throttle Syndicate were matte as well to prevent glaring from the headlight.

When Friday evening came and all of the prep work was done, I was worn out. I told my teammates that I felt like I had already raced 24 hours. I wasn’t the only one feeling this way. The week of the race was jam-packed for everyone; we each had full days of work on our plate, and we spent our evenings and every moment after our day jobs prepping for the race. Tuesday, we all met at Glen Helen at 4:00 p.m. and stayed until 8:00 p.m. testing the bike and the headlight. Wednesday night, I was at Pro Circuit until 8:30 p.m. putting on graphics, new tires on our spare wheels, air filters onto extra cages and, at the end of the night, we practiced pit stops. Then, on Thursday, we were all back to our regular work grind and spent that evening packing our personal vehicles with food and supplies.

Friday morning, I drove the Pro Circuit box van out to Glen Helen to meet Bones, who already had our spot at the end of the pit road saved. Mitch and Bones wanted to be at the end of pit lane for two reasons. One, if anything happened to the bike, then our water boys, who were stationed at the beginning of the pit lane, could radio our pit crew to mention any potential problems. Two, being at the end meant that after we left our pit, we could get on the gas right away and not have to keep riding at the 15-mile-per-hour limit.

Saturday morning was race day. It was go time. The race was set to start at 10:00 a.m. The pre-race morning hours went by quickly. I was the first rider in our lineup, but my start wasn’t great. Thirty minutes before the race would begin, during the riders’ meeting, it was announced that we would do a Le Mans-style start where the riders had to stand in front of the bike with their backs to the green flag. We were allowed to have a pit crew member hold the bike and yell for us to go when the green flag fell. We’d jump on, start the bike and race to the first turn. I practiced this technique three times before heading to the line, and I felt good! But, my adrenaline was pumping for the race. I fumbled getting on the bike and came off the start in fourth place. Luckily, I made quick passes and moved into second before heading into the tight single-track sections.

After battling back and forth for the lead on the first lap, I eventually took over first position. Our team held the lead for the first three hours of the race, only dropping back to second for a few laps and then getting back into first. The lead yo-yoed throughout the day, but we were able to maintain it as other teams had bike issues. Eventually, bike issues struck us, too, but with our team of mechanics on standby, Mitch had no plans to let us be beaten in the pit area. Our first major issue began during my second stint at five hours into the race. I hit false neutrals a handful of times. When I pitted, I told Mitch and Schnikey about it, but they said not to stress over it. Carlen Gardner, who was second in the team lineup, went out for his hour-and-15-minute stint and he hit neutral also. Zac Commans was next, and when he came off the track, his news was more gruesome. He couldn’t get the bike into fourth gear and was having to shift from third up to fifth on the fast straights. The bike continued to get worse for Preston Campbell, who was fourth in the lineup, and when he handed the bike back to me, he was frantically trying to warn me about it before I took off.

I tried to double shift from third to fifth as Zac had done on the fast straights, but I didn’t like it. The tranny was rough, and the bike would chug in fifth. By the time it got going fast enough, I was into the braking bumps of the next corner. I decided to stay in third gear and manage it down the fast parts of the course. I stayed below the rev limiter and tried to make up for any lost time by setting up early and carrying extra momentum through the corners.

“HOW IS IT?” HE ASKED. I YELLED BACK WHILE STILL MOVING, “IT’S GOOD; IT’S PERFECT; IT’S GOOD!” AMAZINGLY, OUR LAP TIMES HADN’T FALLEN OFF WHEN WE COULD ONLY GO AS HIGH AS THIRD GEAR.

After the first lap of my third session on the bike (my first session in the dark), Preston met me at the beginning of the pit area after I went through the tight, low-speed finish line chicane. He stood there in the dark at 7:15 p.m. with his big hands and lanky fingers motioning for me to stop. My ultra-bright lights lit him up like a Christmas tree, and I could see the intensity in his eyes. I slowed but didn’t come to a stop.

“How is it?” he asked. I yelled back while still moving, “It’s good; it’s perfect; it’s good!” Amazingly, our lap times hadn’t fallen off when we could only go as high as third. When I rode by our pit area, I got the loudest cheers of the whole race. Everyone was pumped to hear the bike was still clicking off laps, but the race was far from over.

Each rider was advised of the best way to save the transmission and traded information about the rapidly deteriorating track conditions. Around 10:45 p.m. our second mechanical issue reared its ugly head while Preston was in the saddle. The headlight was flickering. It was still working, but barely. In the pit, Schnikey changed the battery and put on a new headlight. That fixed it, but after one lap the issue came back with the second headlight. On the next lap, Preston pulled in and Schnikey found a loose wire behind the light and fixed it. At this point, Preston had stopped in the pits twice, and he only had two more laps left in his originally planned four-lap stint. But, with the light working and Preston’s lap times really fast, we kept him on the track for an extra lap to try to squeeze some more speed out of him. Since the bike had been refueled during each of his extra pit stops, the bike was okay to go for an extra lap.

For me, the hardest part of the race was waking up from my sleep at 10:30 p.m. and again at 4:00 a.m. to put my gear back on and go ride. Our race strategy called for a little over three hours between sessions. I took time to eat, take my gear off and lie down to try to sleep; however, I only slept for an hour each time because I had to be awake and ready to ride one hour before my scheduled session. That way, if Preston, who was right before me in the lineup, had an issue or injury, I could jump on the bike. The 10 minutes after being awakened were the roughest of the night. Bones had built a campfire next to our pit to keep us warm, and our pit crew was still going strong and cheering for us each lap. That helped me wake up. We had a long list of people who helped us throughout the 24-hour adventure, but Mitch, Schnikey, Averi, Craig, Gothic Jay, John, Nathan and Tyler made up the list of people who didn’t sleep at all.

John Parkinson of PanicRev ministries was our fuel and our lap-time logistics guy. Any time I wanted to know where we were at in the race, I could ask him. He knew how big our lead was, and he had each rider’s lap time marked down on a large whiteboard. With our fastest laps being around the 16-minute, 30-second marks early in the race, we were able to log consistent 17- and 18-minute lap times throughout the night and into the next day, only slowing down to 19- and 20-minute lap times a handful of times, even with our stops in the pits.

Nathan and Tyler were the water boys, and they helped a lot throughout the race. With radios at the beginning of pit lane, they let the pit crew know whenever we entered the pits; they also had water bottles with rubber tubing as straws. This way, we could have a fresh water bottle to drink as we rode through the 30-second-long pit lane. My teammates chose to fill up their USWE hydration packs with water also, but I used my USWE pack to carry a spare battery for my Task Racing helmet light. This way I wasn’t carrying extra weight on the track. If the lap times had been longer, I might have brought water with me, but with an average of 17-minute lap times, one bottle a lap was plenty.

I HAD RACED SUPERCROSS AT NIGHT BUT UNDER BRIGHT STADIUM LIGHTS. NIGHTTIME RIDING AT GLEN HELEN IS SURREAL. IT IS PITCH BLACK, BROKEN ONLY BY YOUR HEADLIGHT DARTING ACROSS THE GROUND.

The night portion of the race was a unique experience. I had raced Supercross at night under bright stadium lights, but nighttime riding at Glen Helen is surreal. It is pitch black, broken only by your headlight darting across the ground. As soon as the sun sank behind Mt. Saint Helen, it felt like midnight—and it continued to feel like midnight until I was riding my fifth and final stint. Throughout the night, Schnikey made sure that our pit crew, those who were awake, were cheering for us each lap. I got on the bike at 5:22 a.m. just as a glint of the sun coming up in the east illuminated the horizon. The sunrise was a beautiful sight and something I had spent most of the night wishing to see. My first lap in the dark was slow, but I woke up as the sun rose and picked up the pace. It was a magical time to ride and something I will never forget.

In the end, I was thankful for how well-prepared we were and I took back my nagging comments about Zac’s notetaking. It took a big effort from every team member to get ready for the 24-hour adventure, but in the end, it paid off. Our bike held up, even after having transmission issues. Our pit crew never wavered, and our riders were smooth and fast. Mitch couldn’t have been happier for the riders, and when Preston Campbell crossed the finish line at 10:05 a.m. on Sunday morning, exactly 24 hours later, Mitch and the whole crew were at the finish line with cheers, high fives and hugs. We had raced for 712 miles and taken the overall victory with an almost two-lap lead.

Mitch, Bones, Schnikey and Gothic Jay dedicated the race to their friend Dave Chase, who passed away in 2009 after working at both Pro Circuit and factory Honda. It was Dave who originally convinced Mitch and the rest of the Pro Circuit shop to race the 24-Hours of Glen Helen in the years prior. Preston, Carlen, Zac and I were proud to bring the long-awaited victory to Pro Circuit—and we now know exactly how to win a 24-hour race.

Comments are closed.