BEST OF JODY’S BOX: THE CADILLAC OF MOTORCYCLES

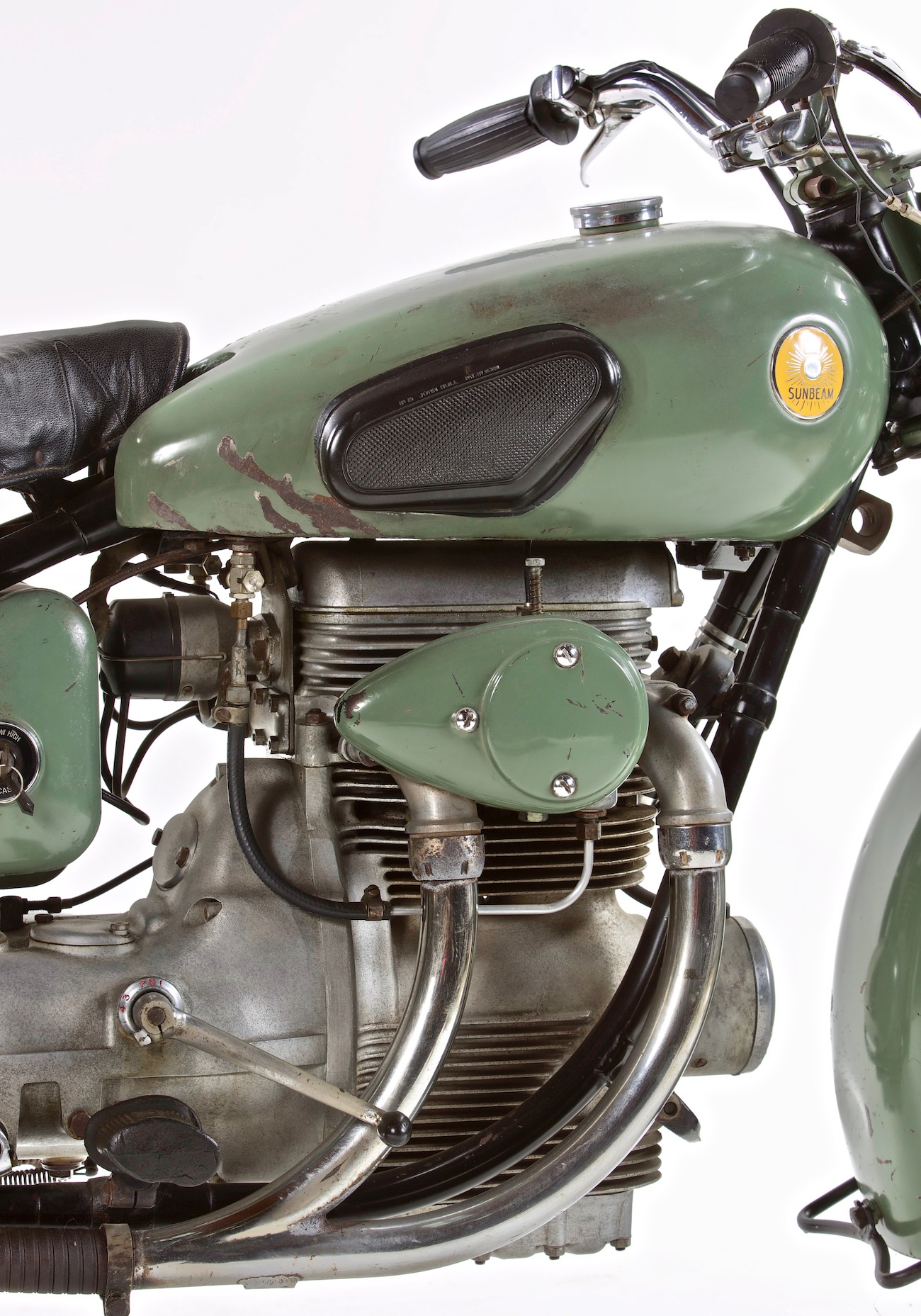

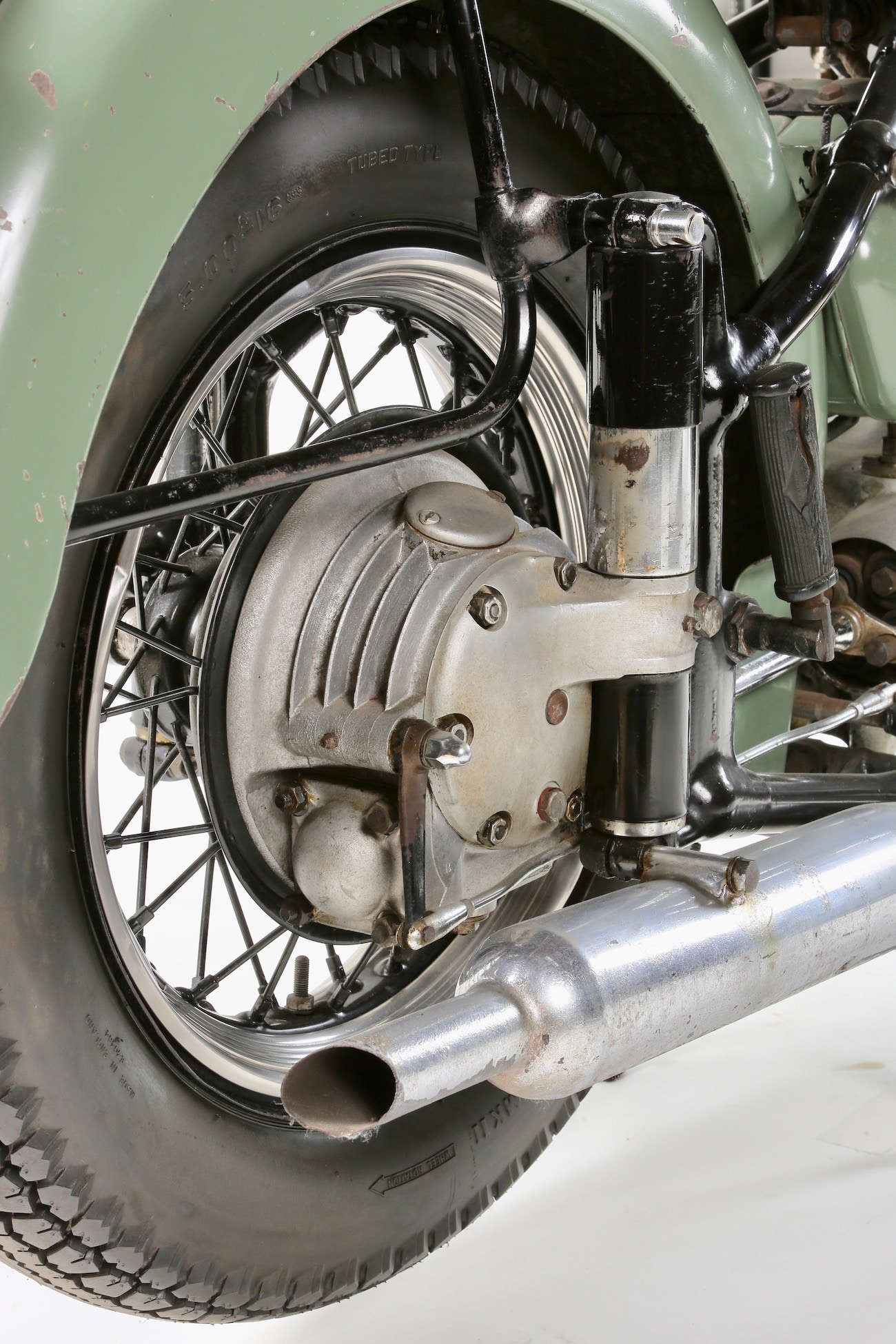

This is my father’s motorcycle. He left it to me when he died. It is in unrestored, original condition. It is a 1953 Sunbeam S7 Deluxe. I still own it, but it sits in a museum. The color is called “Mist Green.” I visit it every now and then. It’s a 500cc, shaft-drive, inline twin with plunger rear suspension. In 1953 the Sunbeam S7 Deluxe was the most expensive bike made.

After WWII, Sunbeam S7s were built by BSA. My brother only rode the S7 one time, and he crashed it, denting the front fork leg. My brother was never allowed to ride it again. After my father’s death, I thought about restoring the S7, but vintage guru Tom White told me that it was more valuable with its original patina. Production on the Sunbeam S7 ended in 1957.

My racing hero BSA icon Feets Minert fixed the Sunbeam’s fork leg for me. After all, it was a BSA fork. A Sunbeam S7 cost twice as much as a comparable BSA model.

I started my long, yet unfinished, motorcycle education with the Sunbeam. I was on the ramp when my father’s KC97 taxied in from a month in England. My mom, brother and I were there to see him land. He didn’t come straight over to us, but instead spent some time with the crew as they unloaded their gear. Then, out of the crowd of airmen came my father riding the mint green Sunbeam S7. He bought it while in England, and when his TDY was over, he loaded it in the belly of his plane and brought it home.

I was a little kid, maybe six years old, but I remember that bike being the most majestic thing I had ever seen. My father was an U.S. Air Force pilot who had flown 25 missions over Germany in a B17 in World War II and lived the hunting, fishing, fast-driving lifestyle that made pilots the manliest of men, but I never really saw him like that until he tooled that Sunbeam across the tarmac.

History unravels like the inner workings of a Swiss watch—one gear turns another, and through countless revolutions the hands of time change. Prior to the arrival of the Sunbeam, the hands on my clock were stuck on Tinker Toys, but once set in motion by this mechanical British marvel, the alarm was set to go off on my motorcycle future. I had never been moved by my father’s Indians or Harleys. In the mind of a preschooler, they were loud, smelly and old-fashioned artifacts. The Sunbeam S7 was a watermark machine for me, and my dad took great joy in letting me sit on the gas tank while he gave me rides on the local roads.

BACK THEN, PARENTS WERE ALLOWED TO SPANK THEIR KIDS AND ENDANGER THEIR LIVES IF THEY SO WISHED. THERE WAS NO NANNY GOVERNMENT TELLING MY FATHER WHAT HE COULD DO WITH HIS KID. ONLY MY MOTHER COULD DO THAT, AND SHE PUT A STOP TO MY GREATEST THRILL.

Of course, there was nothing I could do about my motorcycle future at 6, except sit happily on the gas tank and laugh hilariously as we whistled through the corners at breakneck speeds—neither one of us wearing helmets, and just my tiny hands hanging on to the handlebars. Back then, parents were allowed to spank their kids and endanger their lives if they so wished. There was no nanny government telling my father what he could do with his kid.

Only my mother could do that, and she put a stop to my greatest prepubescent thrill after my father tipped over at 3 mph while pulling into the driveway, spilling me unceremoniously on the lawn.

There were no minicycles made in the 1950s, so I made do with Schwinns and the odd smattering of lawnmower-powered bikes, always favoring Tecumseh over Briggs & Stratton. Then, one day when I was old enough, my father rolled a used Benelli 125 up the driveway (it was marketed as a Riverside 125). It wasn’t much of a machine. It had a stamped steel frame, flared fenders and a two-stroke engine that looked like a pine cone sitting on top of a chrome watermelon. I rode it everywhere in our small town—through every field, backyard, trail, street or sidewalk that looked like there was adventure at the other end.

When it came time to race in 1968, I bought a used Sachs 125 for $300. I was a terror on that thing, missed shifts and all. That got me a shop deal to race the greatest motocross bike of all time—the Hodaka Ace 100. The Super Rat got me a distributor deal, a small modicum of fame and, like the pinion gears in a watch, that time, slowly but surely, became today. I owe it all to my father’s brilliance in buying what he called the “the Cadillac of motorcycles.”

Comments are closed.