THE MXA WRECKING CREW VERSUS THE “GOLF OF OFF-ROAD RIDING”

THE MXA WRECKING CREW VERSUS THE “GOLF OF OFF-ROAD RIDING”

BY JOSH MOSIMAN

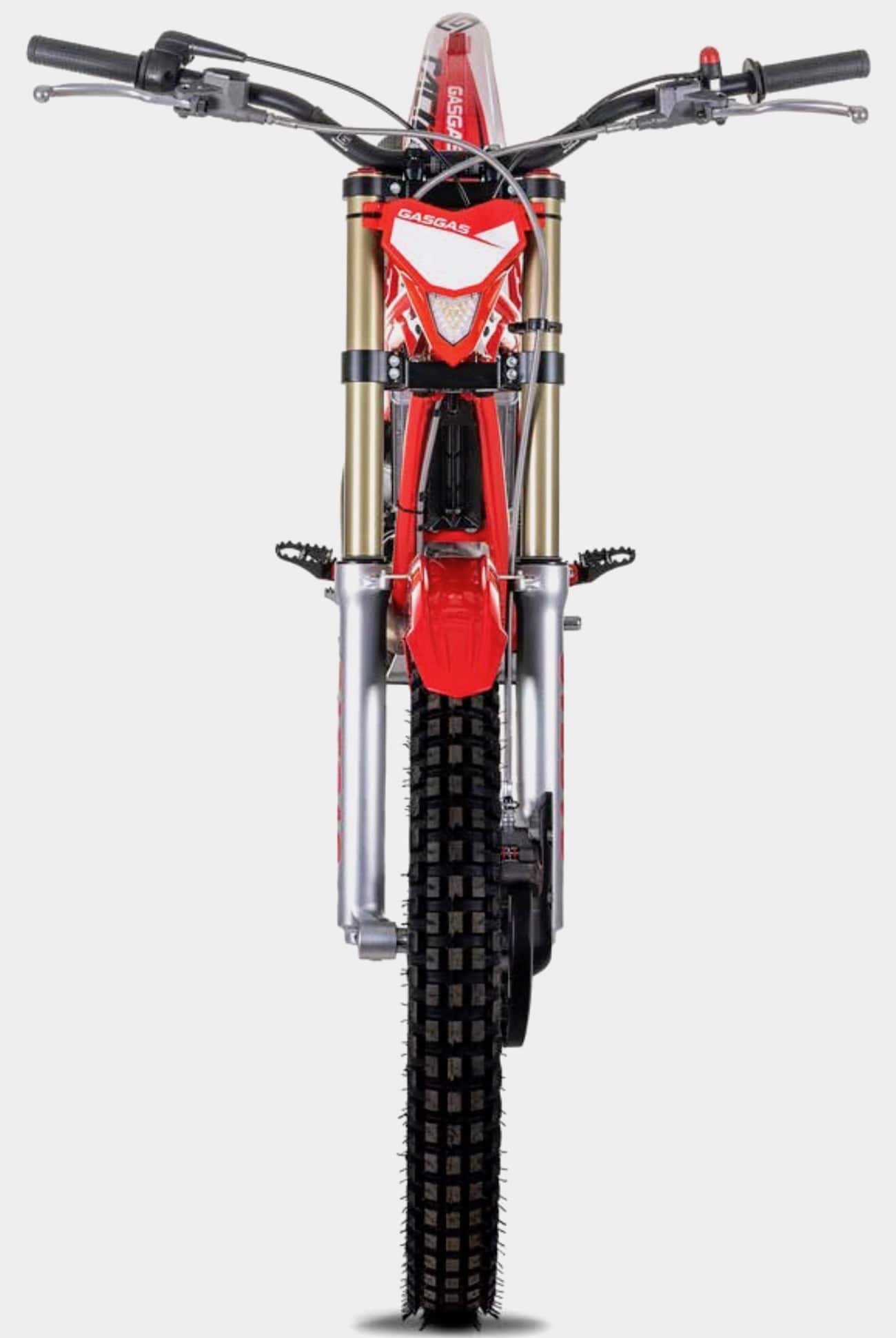

Motocross has been good to me. I’ve traveled the world, worked my way up through the Pro ranks, raced Supercross, earned an AMA National number and gotten the best rides of my life as an MXA editor. What I like best about being at MXA is never knowing what you are going to do next. It’s a great job for an adrenaline junkie—and the MXA wrecking crew, which includes a large cast of crazies, likes to maximize the thrills whenever we get the opportunity to do “something cool.” So, when GasGas asked if MXA would like to go riding with 10-time AMA National Trials Champion Geoff Aaron, Daryl Ecklund and I jumped at the chance—and Dennis Stapleton came along to laugh at us. Not only would we get to ride with an American trials icon, we would get to do it on the first motorcycle out of the new GasGas/KTM/Husqvarna conglomerate—the Gas Gas TXT 250. Now that is “something cool.” Not only were we hot to trot, but we both wanted to be the best first-time trials riders that Geoff had ever seen. Daryl and I always aspire to outdo each other, even if there is no trophy at stake.

The sport of trials riding developed in the early days of motorcycling when riders and manufacturers competed in “reliability trials” to show off how well their machines performed over multiple days in rough terrain. The most famous of these was the Scottish Six-Day Trials. Started in 1910, it was a combination of rough moorland, rocky goat tracks, steep trails and public roads in the best (and worst) weather the Highlands of Scotland could throw at the riders. Trials was never meant to be a race. Instead, it’s a challenge where man and machine work together to traverse otherwise unridable obstacles. Trials riding demands a skillful and precise style. You can’t get away with twisting the throttle and closing your eyes in this sport. In many ways, trials riding is paradoxical to motocross.

Riding with 10-time National Trials Champion Geoff Aaron was a blast. He showed us the ropes and accelerated our learning curve.

Riding with 10-time National Trials Champion Geoff Aaron was a blast. He showed us the ropes and accelerated our learning curve.

Many fans of the sport ask us why KTM would buy a 60-percent share of Black Toro Capitol, the owners of the Spanish GasGas motorcycle brand, when they already control the off-road market with KTM and Husqvarna, especially given that KTM’s plans included platform-sharing the KTM chassis, suspension and engine among its now three brands. But, the icing on the GasGas acquisition wasn’t cloned motocross bikes, cross-country bikes or enduro bikes; it was the only off-road bike that KTM didn’t have—a trials bike.

Trials bikes aren’t made to jump big doubles, hammer through the whoops, hit 70 miles per hour on the way to the Talladega first turn or launch off the gate with 39 other trials bikes fighting for the first corner. Nope! Trials bikes have been bred over the last 110 years to explore terrain that you wouldn’t be able to access on a typical motocross bike. They’re small, low and ultra-light, with super grippy tires, engines that maximize torque over horsepower, and handling that is more shopping cart than high-speed racer. They are designed to go slow—incredibly slow—right up to the moment when they need an explosive burst of torque to clear a boulder or launch off a waterfall.

Heading south through the SoCal landscape, I didn’t know what to expect from our first ride on the Gas Gas TXT 250. Daryl Ecklund had more experience than I did on trials bikes, but that was years ago, before he focused on being a motocross racer. Our Pro from Dover, Geoff Aaron, came with us to ease the shell shock of “plonking,” which is a classic trials word, along at just a hair above minimum chain-snatch speed. Once we were in the boulder field, I hopped on the GasGas TXT 250 and started playing around on the small rocks. I was having fun trying to figure the machine and the sport out. It looks so easy, and it should have been made that much easier by having Geoff demonstrate each technique to us, but that didn’t really help. He made everything look effortless. I made everything look dangerous and sometimes painful.

TRIALS BIKES AREN’T MADE TO JUMP BIG DOUBLES, HAMMER THROUGH THE WHOOPS OR LAUNCH OFF THE GATE WITH 39 OTHER TRIALS BIKES

FIGHTING FOR THE FIRST CORNER. NOPE! THEY ARE DESIGNED

TO GO SLOW—INCREDIBLY SLOW.

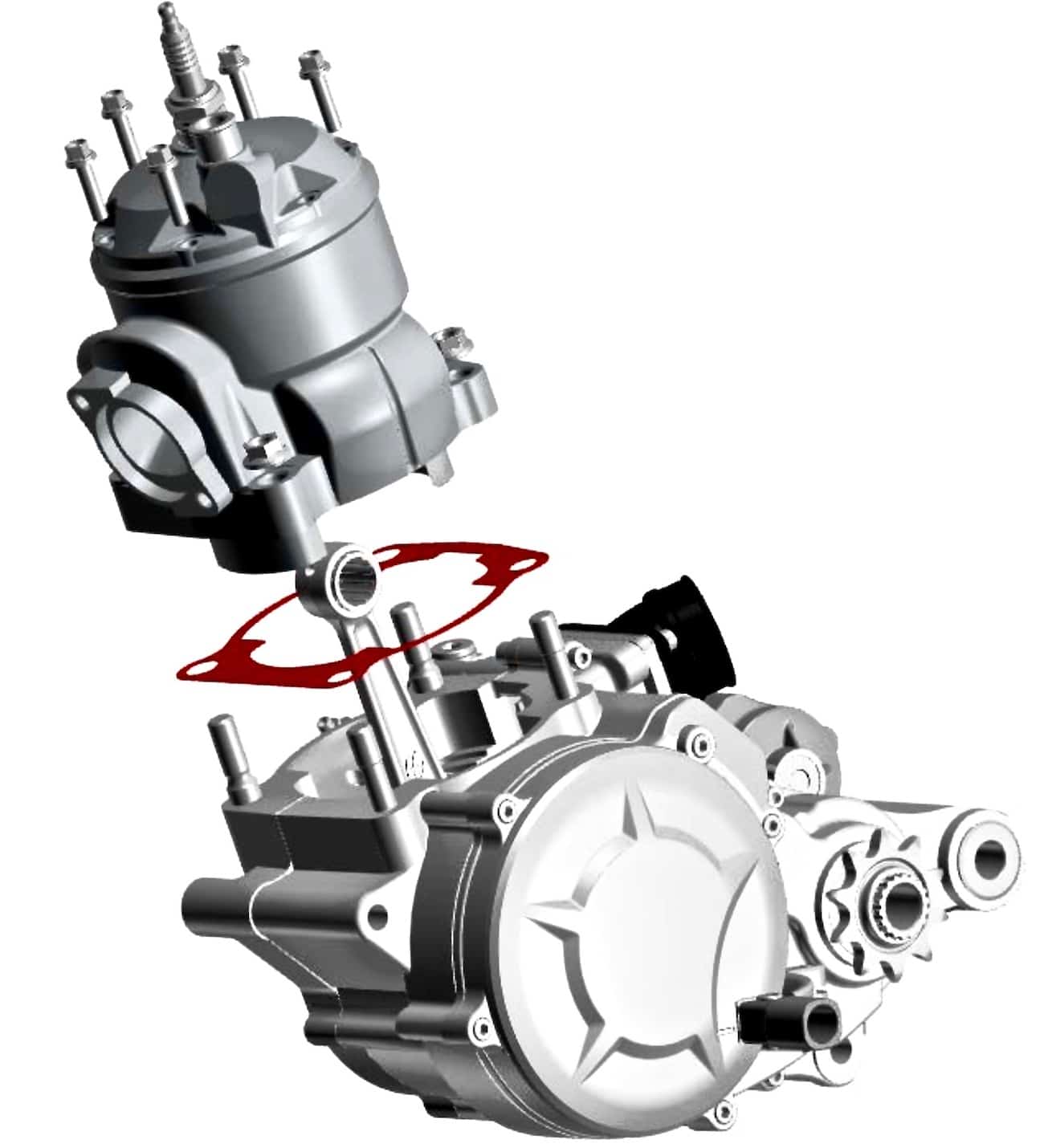

With the ultra-heavy flywheel on the GasGas TXT two-stroke, the engine’s power delivery came on smoothly and revved longer than on a motocross bike. Geoff explained, and then showed us, how the heavy flywheel helped him keep up momentum over big obstacles. At the bottom of a steep boulder about the size of the Rock of Gibraltar, Geoff would rev the engine high into the rpm range, release the clutch and launch forward, only to let off the gas and coast over the top. The extra weight on the flywheel gave the engine a tractor-like effect that kept the rear wheel chugging, even after the throttle was closed. To maintain traction on rocks, GasGas uses a tubeless rear tire that allows for incredibly low tire pressures without fear of getting a flat. The special sticky tires helped the bike grip far beyond where a typical motocross tire would lose traction. I had to trust that the tires would stick. Experience had taught me that dirt bike tires spin, but dirt bike tires don’t have the rubber durometer of an eraser.

The objective in trials riding is to navigate through difficult sections without touching your foot to the ground. As soon as your foot touches one time, practically all credibility is lost. Geoff explained trials competitions by saying, “It’s the golf of motorcycle racing.”

A trials course is laid out similarly to a big mountain bike loop in the woods. The riders (you can’t really call them racers) follow the cross-country course until they arrive at a “test section.” It is marked off, often in a serpentine pattern, through very difficult terrain that is highlighted by steep climbs or boulders. The test sections are new to the riders, but once at the test section they are allowed to walk the course before they make their run. There is a judge stationed at each test section to count how many times your foot touches the ground, which is called a “dab.” The judge at each test section marks down how many dabs you had to do to make it through the section. The rider with the fewest dabs over all the sections is the winner. The rider can have his mechanic or coach walk the section with him, much like a caddy in golf. In golf, caddies are there for support and to make suggestions about which club might be best for each hole.

In Pro trials events, a mechanic (caddy, tender, helper, coach) dresses in matching gear and follows his rider around the course on a matching trials bike; the only parts of the course the caddy doesn’t actually ride are the test sections. In a way, professional trials is a team sport, with the rider and his helper planning the strategy together. Unlike the brutal, lonely, man-against-man nature of motocross, trials riding demands a calculated and skillful technique, but it is every bit as challenging as motocross. Comparing motocross and trials is like comparing hockey and golf.

Many years ago, the sport of trials was about riding the motorcycle through the test sections with careful line selection and a constant, albeit slow, forward momentum. All that changed when BMX-bred riders entered the sport and introduced bunny hopping. Instead of riding a section in a continuous flow, bunny hopping allowed the riders to stop and bunny hop to the left, to the right and straight up onto the rocks and logs. For me, hopping on the trials bike from a dead stop was the most difficult thing to master. As a motocross racer, I was always tempted to blast through the section and hit the rocks wide open.

Geoff Aaron made it look so easy that we actually lost confidence in ourselves. Josh Mosiman doubts himself at the crux moment.

Geoff Aaron made it look so easy that we actually lost confidence in ourselves. Josh Mosiman doubts himself at the crux moment.

Jody, who had some trials experience on Honda’s short-lived TL125 trials bike back in 1973–’74, warned me not to race from test section to test section, because a trials bike’s geometry is very steep, which causes a lot of head shake at speed. Still, I had to try it. Frankly, it wasn’t as bad as I expected. The top three gears in the six-speed transmission of the GasGas TXT 250 are used for transferring from section to section, while the bottom three are used primarily in the technical sections. The steep head angle is necessary for ultra-sharp turning, and the absence of a seat forces you to stand up. It’s an understatement to say the bikes aren’t comfortable for long treks; however, they are specially designed to operate with precision in the most difficult spots.

During our day with Geoff, we ran through a series of test sections. The first section was extremely fun. It was a little trail through a dry creek bed. The section was about 200 feet long, and it was tough! Daryl and I made our way through it, and after our first few runs, we agreed we would have done better on our normal dirt bikes. But, with Geoff’s help, we started to adopt the correct way to ride a trials bike. Our natural inclination, whenever we got into a harry situation, was to pin it. It was really funny to watch us on trials bikes, because “pinning it” is totally opposite from what you’re supposed to do. Instead of picking our way gracefully through the tough parts of the section, we would panic, hammer the throttle and try to wheelie out of it. In motocross, that’s the normal and correct reaction; but in trials, it doesn’t work, and we only got away with it on the easy stuff.

INSTEAD OF PICKING OUR WAY GRACEFULLY THROUGH THE TOUGH PARTS OF THE SECTION, WE WOULD PANIC, HAMMER THE THROTTLE AND TRY TO WHEELIE OUT OF IT. IN MOTOCROSS, THAT’S THE NORMAL AND CORRECT REACTION. BUT IN TRIALS, IT DOESN’T WORK.

In motocross and Supercross, I always focused on squeezing with my legs to grip the bike and lean with it going into corners. But, in trials, Geoff taught us to do the exact opposite. We needed to let the bike do what it wanted and keep our body’s weight centered over it, without gripping the bike. Weighing only 148 pounds with Velcro-like tires and soft suspension, the TXT250 was capable of maintaining traction in places I never dreamed of. But, it only worked when my body stayed centered and balanced. On a motocross bike, I rely on forward momentum to keep me from falling over. But the slow pace of trials riding requires a different set of physics. My body weight was used for balance, while the bike moved in any direction it needed to keep traction. Once Geoff convinced me to stop gripping with my legs and let the bike do what it wanted, I was much smoother.

The bike is capable of scaling massive rock faces and stopping on a dime, but only if the rider is willing to make it happen. It takes serious commitment—think of it like the first time you try a big double on a motocross track. You are nervous but excited. After conquering some small rock faces, Daryl and I wanted to climb something that we could be proud of. Geoff Aaron picked out a gnarly 4-foot-tall rock with vertical sides and a gradual slope on the backside. It was perfect, just enough to intimidate us but still within our minimal capabilities.

After spending a few minutes looking at the rock and talking to Geoff about the proper tactics to scale it, Daryl went first. I was thrilled when he made it up and over the boulder on the first try. It was awesome to see, but his next few tries didn’t go as well. In his worst attempt, he cased the top of the boulder and fell backwards off the rock, while the GasGas landed on its revved-up rear wheel and did a backflip, just missing Daryl as he scrambled away from it.

THE BIKE IS CAPABLE OF SCALING MASSIVE ROCK FACES AND STOPPING ON A DIME, BUT ONLY IF THE RIDER IS WILLING TO MAKE IT HAPPEN. IT TAKES SERIOUS COMMITMENT—THINK OF IT LIKE THE FIRST TIME YOU TRY A BIG DOUBLE ON A MOTOCROSS TRACK.

Now it was my turn. It was a crash course in rock-wall climbing. When I finally mustered up the courage, I hit the face of the rock with my rear wheel and tried to bounce the bike up and over the boulder. It didn’t work. Right at the apex, my feet flew off the pegs, and I bailed off the bike to avoid having both of us fall backwards to the ground. After a couple attempts with the same outcome, Geoff told me to stop trying to use the rear wheel for thrust and instead bounce my front tire on the rock face and then let that bounce me up and over it. I struggled to wrap my mind around that idea. I’m used to wheeling over bumps or using acceleration from the rear wheel to get my front tire over the top of a step-up.

I had never intentionally slammed into a vertical jump front wheel first. He even showed me how to do it as though it were as easy as pie. But, I couldn’t make it over the rock wall, and I couldn’t stop trying. I felt that if I stopped, I wouldn’t get the courage to try it again. Geoff decided that it was in GasGas’ and my best interest to stand at the top of the rock to try to catch the bike if I ditched it again. At least that way it wouldn’t land on me as I lay on the ground. Finally, I made it up and over the rock. It felt good! But, I dabbed my foot once on the top edge of the boulder. I felt that dabbing my foot when I finally made it over the rock was better than dabbing my head on the ground the five times I failed to make it.

Geoff Aaron has been a GasGas-sponsored trials rider since 2000, and he worked for the company when it was bought by KTM in 2019. He’s happy to stick with GasGas for the next chapter.

Geoff Aaron has been a GasGas-sponsored trials rider since 2000, and he worked for the company when it was bought by KTM in 2019. He’s happy to stick with GasGas for the next chapter.

Once I made it over the boulder, I was inspired. I started looking for more boulders, and every day after MXA’s experience with Geoff Aaron, I took the GasGas into the hills to see what kind of trouble I could get into. My mind was officially changed. Now that I had faced my biggest demon, in the shape of a boulder, I could see the fun that trials had to offer. I learned a few techniques that could transfer over to motocross. Riding trials takes laser focus, exacting precision, perfect balance and the utmost confidence. Improving in each of those areas pays big dividends in motocross, no matter your skill level or age. The biggest plus was that I could amuse myself for hours within a relatively small area. If you have a backyard, I can almost guarantee you have enough room to practice trials riding. Whisper quiet, trails bikes are neighbor-friendly. The low-horsepower engines are stealthy, and the bikes barely kick up any dust. Oh yeah, the skill that came in most handy during my first day riding trials was the ability to land on my feet.

Comments are closed.