1992 YAMAHA WR500: HOW THE “AIR HAMMER” BECAME THE “MAYTAG”

THE NEW BIKE, CALLED THE YAMAHA WR500, WAS AN AMALGAMATION OF YZ250 AND YZ490 PARTS. IT WAS BOTH AN OLD BIKE AND A NEW BIKE AT THE SAME TIME.

BY JODY WEISEL

Today, 500cc two-stroke motocross bikes are looked back on, mostly by people who never raced them in anger, with rose-colored glasses. That rosy vision is clouded by a veil of gauze. The 500’s aura wasn’t based on brand participation, fan approval or a strong following of local 500 racers. What gave the 500s the aura that surrounds them today was their exclusivity. What exclusivity? Of all the men who have ever raced 500cc two-strokes, only a few ever rode them to 85 percent of their potential, which paradoxically means the 500cc two-strokes were popular because so few could ride them. It was a man’s machine. The 125 class was for schoolboys. The 250 class was for paperboys. And the 500 class was for men.

But, by 1985, men were in short supply, and just as rapidly 500cc motocross bikes began to disappear from the showroom floors. Suzuki was first. Suzuki won its one and only 500cc National Championship in 1979. After that high point, Suzuki continued to contest the class until 1983 (with Alan King, Kent Howerton, Marty Smith and 1979 Champ Danny LaPorte). In 1983, Suzuki upped the displacement of the RM465 from 464cc to 492cc and renamed it the RM500, but by 1984 the Suzuki sales department said that there weren’t enough sales to justify continuing to produce the bike. The AMA 500 Nationals would continue for nine more years without any Suzukis on the track.

In 1989 the venerable Yamaha YZ490 (and we say “venerable,” because it saw very few significant changes after its introduction in 1982 when it replaced the YZ465) was dropped from the Yamaha product portfolio. With Pierre Karsmakers (1973), Jim Weinert (1975), Rick Burgett (1978) and Broc Glover (1981/’83/’85), Yamaha won six AMA 500 National Championships. Glover’s three 500 Championships were all the more amazing because he piloted the antiquated, air-cooled Yamaha YZ490 against the incredible $50,000 works Honda RC500s of Chuck Sun, Danny LaPorte, Rick Johnson, Magoo Chandler and David Bailey. Jeff Stanton was the last Yamaha factory rider to race the YZ490 in 1988, but its last win was under Broc Glover back in 1985.

THE POPULARITY OF 500cc MOTOCROSS BIKES WAS TAKING A SUDDEN NOSEDIVE WITH CONSUMERS. DEALERS COULDN’T GIVE THEM AWAY. AT THE DARKEST MOMENT, YAMAHA RODE IN ON A WHITE

HORSE TO SAVE THE CLASS.

The YZ490 wasn’t on the showroom floors by 1989 (although leftovers were). Only Kawasaki and Honda were carrying the Open-class torch, aided by a smattering of KTMs and ATKs. With 500cc bike sales in the tank and the 500 Nationals degenerating into a two-brand class, the popularity of 500cc motocross bikes was taking a sudden nosedive with consumers. Dealers couldn’t give them away, and most Japanese production lines were only producing the bare minimum to meet the declining demand. At the darkest moment, Yamaha rode in on a white horse to save the class, the 500cc two-stroke breed, and the careers of Damon Bradshaw and Doug Dubach—although neither Damon nor Doug were too keen to ride their galloping white steeds into the fray.

Back at Yamaha headquarters, the Yamaha execs decided to take another shot at building a 500cc two-stroke. But, not surprisingly, they didn’t want to invest a lot of money in the project—money on a project that many in the company said would fail within a year. The Yamaha race team built two prototypes of a YZ490 engine shoehorned into a YZ250 chassis. The prototypes worked and, best of all, didn’t require a lot of R&D—just a few mods to cure the YZ490 engine’s pinging problems. The new bike, called the Yamaha WR500, was an amalgamation of YZ250 and YZ490 parts. It was both an old bike and a new bike at the same time (the engine had already achieved museum status, while the frame was based on the latest YZ250 model). When it hit the showrooms in April of 1991, Yamaha billed the WR500 as a 1992 model, even though it was six months too early to be a 1992 and six months too late to be a 1991. MXA called it the 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500. Yamaha ballyhooed the WR500 for months leading up to its release, ginning up demand for what became a mixture of fantasy, fallacy and fact.

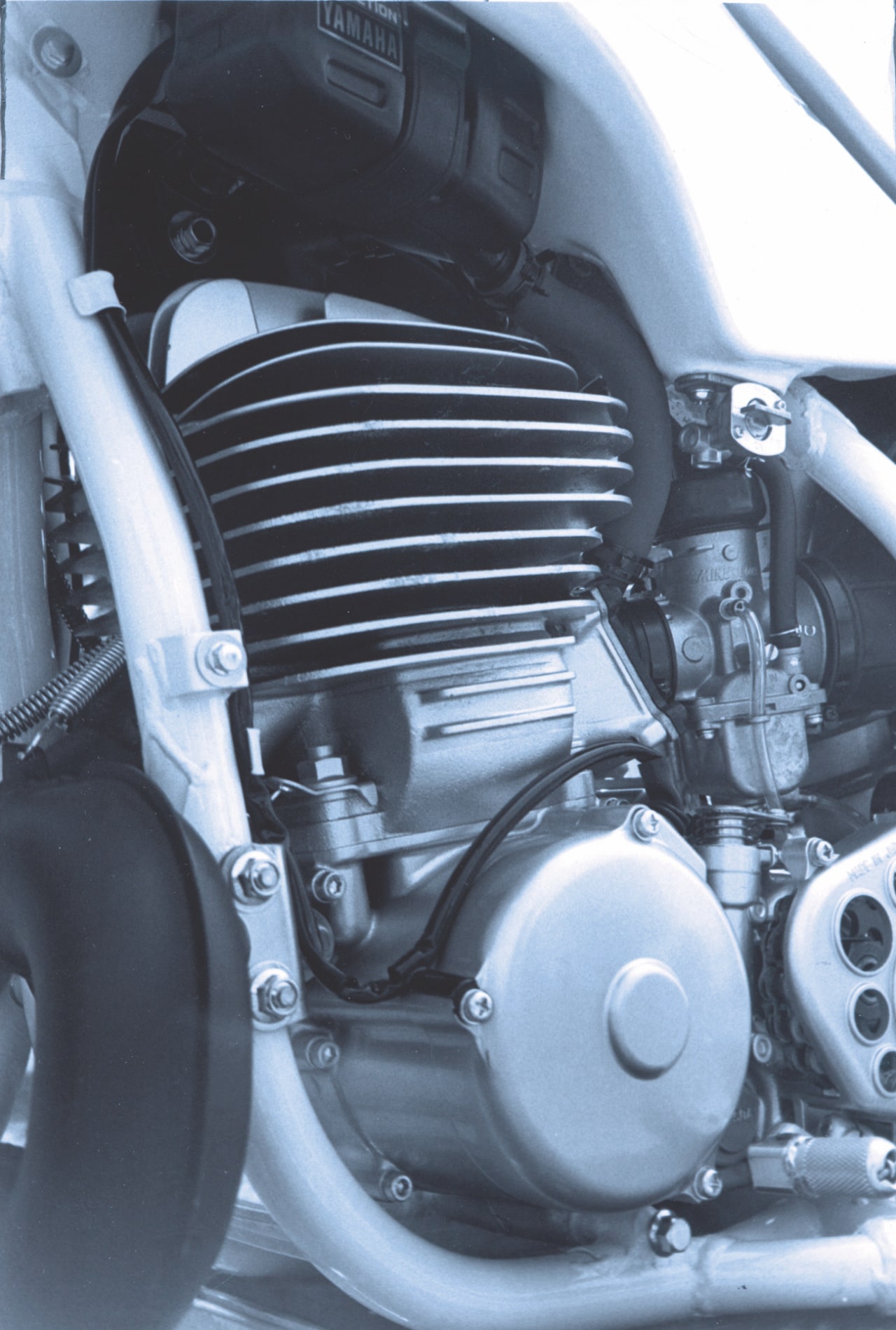

The YZ490 engine, which was mellowed out to become the WR500 engine, was easily identifiable by its black boost bottle.

The YZ490 engine, which was mellowed out to become the WR500 engine, was easily identifiable by its black boost bottle.

First off, although Yamaha called it a 1992 model, there was very little on the WR500 that recommended it as a 1992 model. Most MXA test riders called the WR500 a “Japanese ATK.” The ATK connection comes largely because ATK was making a killing selling air-cooled, Rotax-powered two-strokes to off-road and woods riders who were reluctant to accept water-cooled bikes. It is no secret that Yamaha was embarrassed by the fact that ATK was able to sell air-cooled off-road bikes during the same period that the YZ490 was dying on the showroom floors (1988–’89). Yamaha did not appreciate the 1991-1/2 WR500 being compared to an ATK, but it was an accurate observation. Because of ATK’s success in the off-road market, the WR500 was not designed to be a motocross bike; instead, it was aimed at the conscientious objectors who rode off-road bikes and eschewed the complexity of radiators, hoses and pumps. It was officially an off-road bike, not a motocross bike, and the WR label, which stood for “Wide Ratio,” was tacked on to bring that point home. Paradoxically, there was nothing “wide ratio” about the WR gearbox. In fact, it was the exact same transmission that came in the 1988 YZ490, but with a 15-tooth countershaft sprocket and 50-tooth rear cog instead of the YZ490’s 14/49 gearing.

“PEOPLE THOUGHT THAT I WAS DOING PROTOTYPE TESTING ON THE 1991-1/2 WR500, BUT THAT WASN’T TRUE. NO ONE FROM THE SECOND FLOOR (REFERRING TO THE YAMAHA EXECUTIVES) KNEW ANYTHING ABOUT IT.” —DOUG DUBACH

Compared to the previous YZ490 the WR500 was a better bike, but in the interim between them the WR500 became antiquated.

Compared to the previous YZ490 the WR500 was a better bike, but in the interim between them the WR500 became antiquated.

The 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 engine was basically the same engine that first surfaced eight years earlier on the YZ490; however, the air-cooled, boost-bottled, five-speed, 498cc engine in the WR500 was not the same YZ490 engine that a decade of motocross racers grew to hate. The old YZ490 engine was one of the few big bores that lacked bottom end. It compounded its poor bottom end by hitting hard in the midrange and zinging off into a high-revving top end. The complete powerband was the opposite of the much-sought-after, torquey, tractor-like Open bikes that consumers were yearning for. To make matters worse, the old engine pinged (detonated) whenever there was a headwind.

Conversely, the 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 engine was mellow, torquey and blessed with a pleasant grunt from low to mid. The old YZ490 powerband had been replaced with a kinder and gentler powerband. Because the cylinder head’s squish was reshaped by changing the 22-degree squish band to a more gradual 20 degrees, the WR500 engine didn’t ping as badly as it had in its YZ490 guise. Helping out was new jetting, which felt rich, but any attempt to lean it out brought back the death rattle. The big 40mm Mikuni was dropped for a smaller 38mm VM38SS Mikuni. The little carb was a big improvement, especially in starting, low-end throttle response and midrange power. The ignition featured a lighting coil (35-watt), less advance (1.7mm from 2.0mm) and the same flywheel as the 490. Compression was dropped from 6.9:1 to 6.64:1 to aid in getting rid of the pinging. Also, there was a new, stiffer lower engine mount to try to reduce vibration and, of course, new head stays to align with the taller YZ490 head.

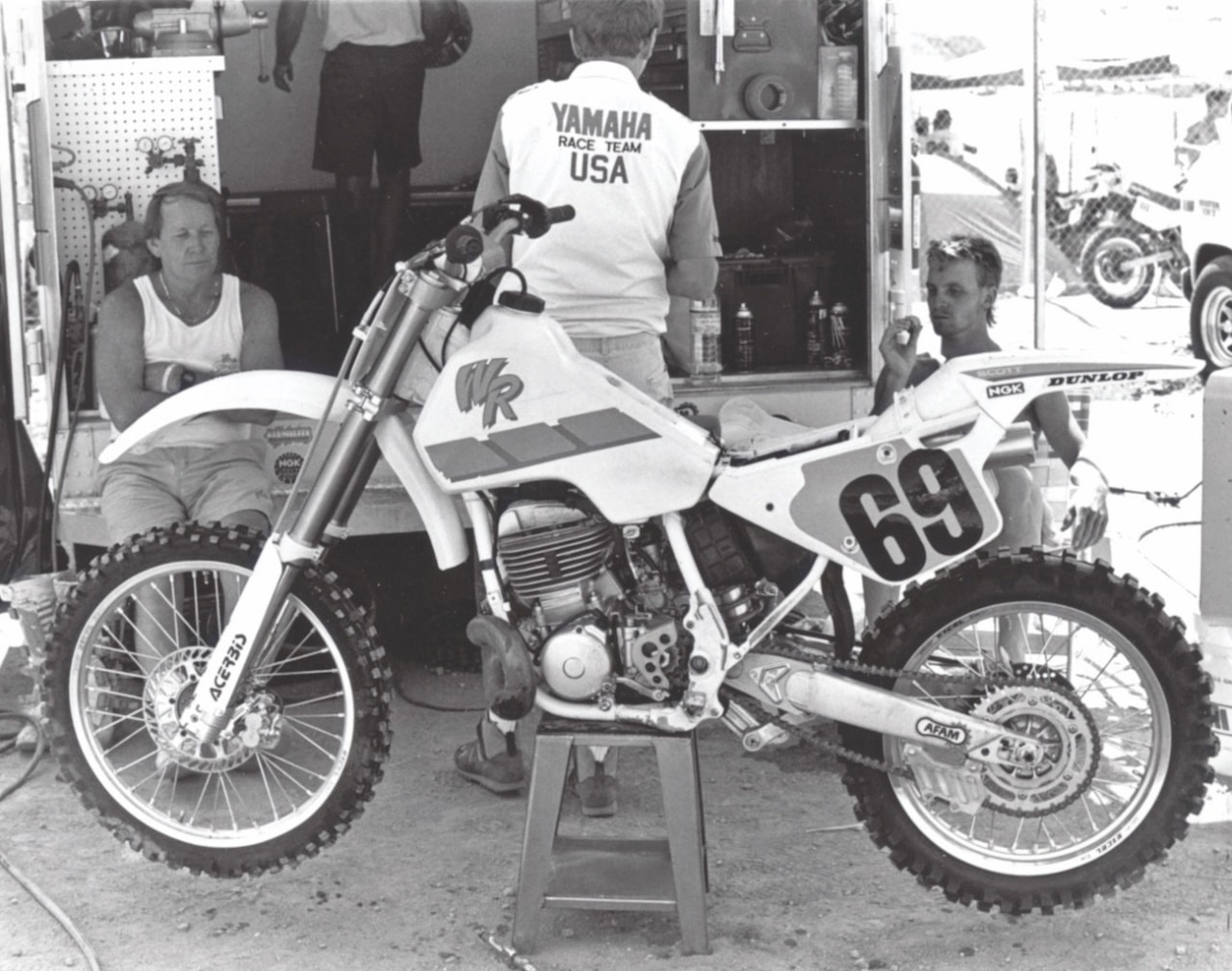

Damon Bradshaw (right) and his WR500 at the 1991 USGP.

Damon Bradshaw (right) and his WR500 at the 1991 USGP.

To help sell the 1991-1/2 WR500 to the general public, Yamaha decided that since the 1991 AMA National schedule was 12 races long, with six 250 Nationals and six 500 Nationals and 125 Nationals at every round, they would have factory riders Damon Bradshaw and Doug Dubach race the first six 250 Nationals and then switch to the six 500 Nationals (that didn’t start until late August). It was marketing 101. They had two available factory riders and a brand-new bike that needed publicity. It was a marketing man’s dream come true for the WR500. Doug and Damon came out of the 1991 AMA 250 Nationals in third and sixth respectively but had mixed feelings about racing the unproven WR500 in the 500 Nationals. The year before the WR500 was introduced, Doug Dubach wanted to race all three Pro classes at Mammoth Mountain. Mammoth was a one-off race that took place during a break in the AMA schedule. Doug wanted to win the combined 125/250/500 overall title at the Mammoth Mountain Motocross but needed an Open-class bike to get the job done. Doug had raced a Yamaha YZ490 at three of the four 1987 500 Nationals and knew that he didn’t want to race Mammoth on the discontinued YZ490. So, mechanic Steve Butler built Doug a special YZ250 with a YZ490 engine wedged in it.

Doug remembers the bike: “Steve used my old YZ250 Supercross frame and Jeff Stanton’s 1987 works YZ490 engine. Steve built it on his own time. It had nothing to do with the WR500 project, because we didn’t even know that Yamaha had that design on the drawing boards. I actually won the combined Mammoth crown by passing Johnny O’Mara in the last turn. And that was the last time I ever raced that bike. People thought that I was doing prototype testing on the 1991-1/2 WR500, but that wasn’t true. No one from the second floor (referring to the Yamaha executives) knew anything about it.

“Many fans think that the WR500 was a USA-only driven project, but Yamaha Japan did all the testing. I was testing for the Yamaha YZ group, and I never saw the WR500 until it was done. Then one day, when Damon and I were doing Supercross testing, Keith McCarty told us that the plans were changed and that we were going to race the WR500 in the 500 Nationals. I didn’t really care, because I had that Mammoth race under my belt and was comfortable with the YZ250/YZ490 hybrid idea, but Damon wasn’t happy about it. He didn’t want to do it, but our Yamaha contracts were for the 12 AMA Nationals, so he didn’t really have a choice.

“Once Keith made it clear that we were going to be on the WR500, we pressed to make sure that we got the good parts. I had raced the 1989 500 Nationals, along with Micky Dymond and Steve Lamson, on an Ohlins-kitted Yamaha YZ360, so the WR500 didn’t seem like a big deal.”

“WE HAD TO RACE WITH THE 3.43-GALLON WR500 FUEL TANK FOR MARKETING PURPOSES. YAMAHA DID TESTS WHERE THEY MEASURED THE FUEL WITH A BEAKER TO FIND THE MINIMUM AMOUNT OF GAS WE WOULD NEED FOR

A 45-MINUTE MOTO. WE RAN THOSE GIANT TANKS ABOUT 2/3 FULL.” —DOUG DUBACH

Bradshaw’s and Dubach’s works WR500s got the good parts (works Kayaba suspension, billet triple clamps and magnesium hubs and parts) and a few tricks that no one ever saw. Doug explained, “When the first few WR500s came to the USA, the team started making parts for our race bikes. Steve Butler’s 1990 Mammoth Mountain bike had used a “real” YZ250 frame, but the bikes we raced in the 1991 AMA 500 Nationals had production WR500 frames. They had to be modified to work in motocross. The works WR500s that we raced had CNC-machined engine cases that moved the engine up to get the countershaft sprocket closer to the swingarm pivot. Because the head angle on the WR500 was 1 degree slacker than a YZ250 frame (28.1 degrees instead of 27.5 degrees), Yamaha machined adjustable steering head races that allowed us to change the angle of the forks. The WR500 was a very tall bike. The team lowered it with a shorter shock and by sliding the forks up in the triple clamps (Damon went up higher than I did). We even went so far as to put thinner rubber pads under the gas tank to move it down a little.

“The clutch suffered from ‘creep’ on the starting line. I complained about the WR500 moving even though the clutch was pulled in. Yamaha came up with a better all-around clutch and a new push-rod lever that was longer. Bob Oliver ported the cylinder, milled the base by 1mm, lowered the intake ports and polished the transfer ports. Although it was possible to run a YZ250 gas tank and radiator wings on the WR500 frame without much trouble, we had to race with the 3.43-gallon WR500 fuel tank for marketing purposes. Yamaha did tests where they measured the fuel with a beaker to find the minimum amount of gas that we would need for a 45-minute moto. We ran those giant tanks about 2/3 full.

Note the rubber dampers between the cylinder fins to lessen ringing. The WR500 engine best trait was that it didn’t ping as bad as the YZ490 version.

Note the rubber dampers between the cylinder fins to lessen ringing. The WR500 engine best trait was that it didn’t ping as bad as the YZ490 version.

“The first 500 National was in Millville in late August. We went there early to make sure that everything was taken care of, but that week my best friend, Paul Donnelly, was killed in a riding accident. I had lived with him before he got married. I got the bad news on Wednesday, flew home on Thursday to be at his wake on Friday and flew back Saturday. It was a less-than-happy start to the 1991 500 Nationals. I don’t even remember the race.

As the series progressed, the WR500 proved to be much better than the YZ490 that I had raced before. I truly believed that we could come away with at least one overall win. I did fairly well in the 1989 AMA 500 Nationals when I competed on a YZ360, so I felt that if I could ride the same bike with a 490 engine, I would have an even better chance of winning. I don’t think the WR500 was anywhere near as advanced as the water-cooled, power valve-equipped works bikes of Bayle, Stanton, Ward and Lechien, but Damon was a very consistent third in five of the six races, won a moto at Broome-Tioga and ended the series in third overall. I just missed the top 10 in points, even though I missed the race after Paul died and had to skip Budds Creek to test in Japan.

“My favorite thing about the WR500 was that the chassis was mellow and handled fairly well. As with all Open-class bikes, it was too fast for my tastes, especially after it was worked on. We started with the basic engine specs that Jeff Stanton had used when he raced the YZ490 in 1987, and the race team handed the engine and pipe work over to Pro Circuit. I wanted the engine tamed some. I had two practice bikes and my race bike. From the time the 1991 Supercross series ended until the 500 Nationals started, I only rode those WR500s. And, when that final 500 National was over on October 13, 1991, I never saw my WR500 again. My practice bikes went back into Yamaha’s loan pool, and the race bikes were parted out to get the works stuff back. As with all works bikes from the past, it is still possible for an enterprising collector to gather up enough exotic parts to build a replica. The WR500 was not a sales success, but on lots of levels it was quite a unique machine, and Yamaha deserves credit for trying to do something about declining 500cc sales numbers.”

THE YAMAHA YZ490 WAS DERISIVELY CALLED THE “AIR HAMMER” BECAUSE OF THE STRANGE NOISES EMANATING FROM THE AIR-COOLED ENGINE. WHEN THE 490 ENGINE CAME BACK IN THE 1992 YAMAHA WR500, IT WAS CALLED THE “MAYTAG” BECAUSE IT VIBRATED SO MUCH.

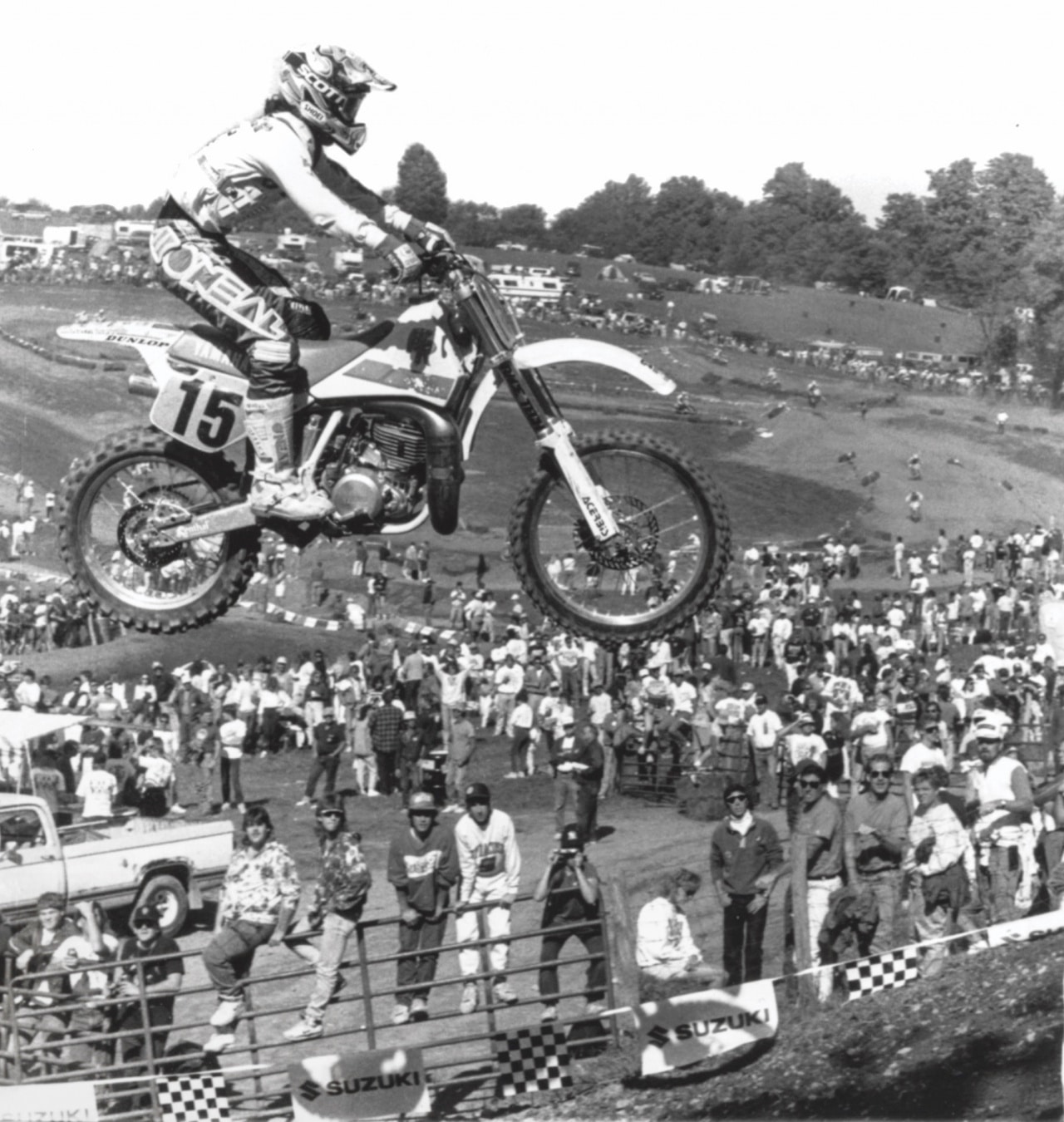

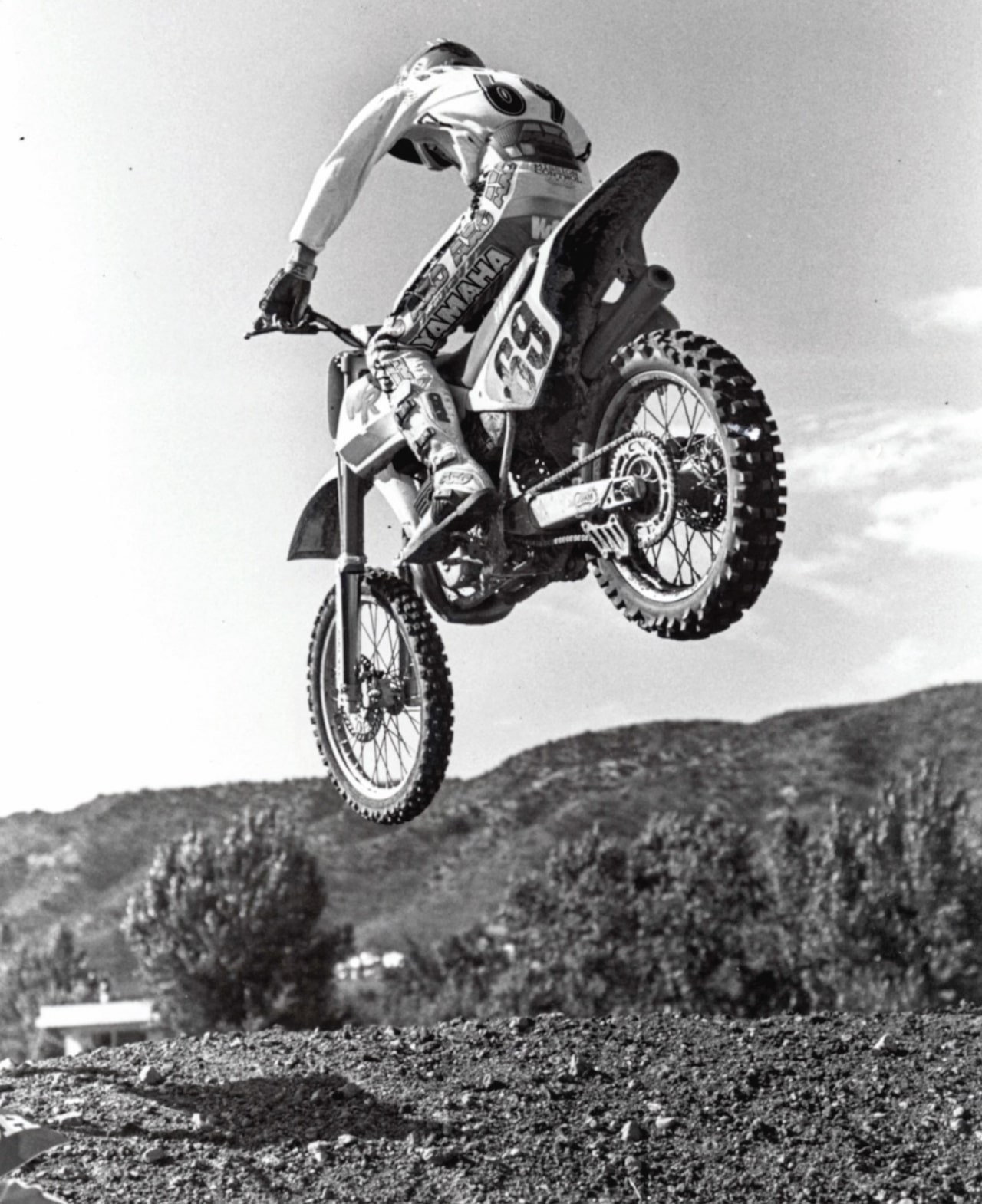

Doug Dubach (15) sailing his WR500 during the 1991 AMA 500 Nationals.

Doug Dubach (15) sailing his WR500 during the 1991 AMA 500 Nationals.

HERE ARE SOME WR500 FACTS

(1) The Yamaha YZ490 was derisively called the “Air Hammer” because of the strange noises emanating from the air-cooled engine. When the 490 engine came back in the 1992 Yamaha WR500, with rubber dampers between the cylinder fins, it was called the “Maytag” because it vibrated so much.

(2) Only 1000 WR500s were made, and they languished on the showroom floors for two model years (1992-1993). Sales of the WR500, which was introduced to pick up lagging demand, turned out to be a mere drop in the bucket compared to YZ490 sales in 1985.

(3) We use the word “shoehorn” to describe installing the YZ490 engine into the YZ250 frame, but, in truth, it slips right in once you make new front motor mounts and head stays.

(4) Yamaha kicked the head angle out on the WR500 1 degree to give the WR500 improved high-speed stability. Overall, the Yamaha WR500 was a steady, stable and predictable handler. It lacked the quickness of a motocross bike, but could hold a line at speed and could negotiate tracks that weren’t too tight.

(5) The WR500 weighed 20 pounds more than the YZ250 and had an 8mm-longer swingarm, but the shock linkage was straight off the YZ250. Back in 1991, MXA swapped out the WR500 shock for the better-damped YZ250 shock.

The stock Kayaba forks mimicked the 1991 KX250 forks.

The stock Kayaba forks mimicked the 1991 KX250 forks.

(6) The 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 frame was the first-ever Yamaha with a completely removable subframe. The workmanship was cobby, but the system worked well. As an added and useless bonus, the left-side tube on the subframe that could previously be removed by itself was still a separate piece on the WR500.

(7) The displacement of the production WR500 was actually 493cc, but if you bored it one-over, it would jump up to 499cc. Two-over made it a 510cc displacement.

(8) The WR500 plastic was identical to the 1991–1992 WR250 parts. Model nomenclature for the 1992 is WR500ZD, and for the 1993 it is WR500ZE.

(9) The stock 1991-1/2 WR500 weighed 238 pounds. Damon Bradshaw’s WR500 went through AMA Tech at 225.5 pounds (which at the time was almost the AMA minimum weight).

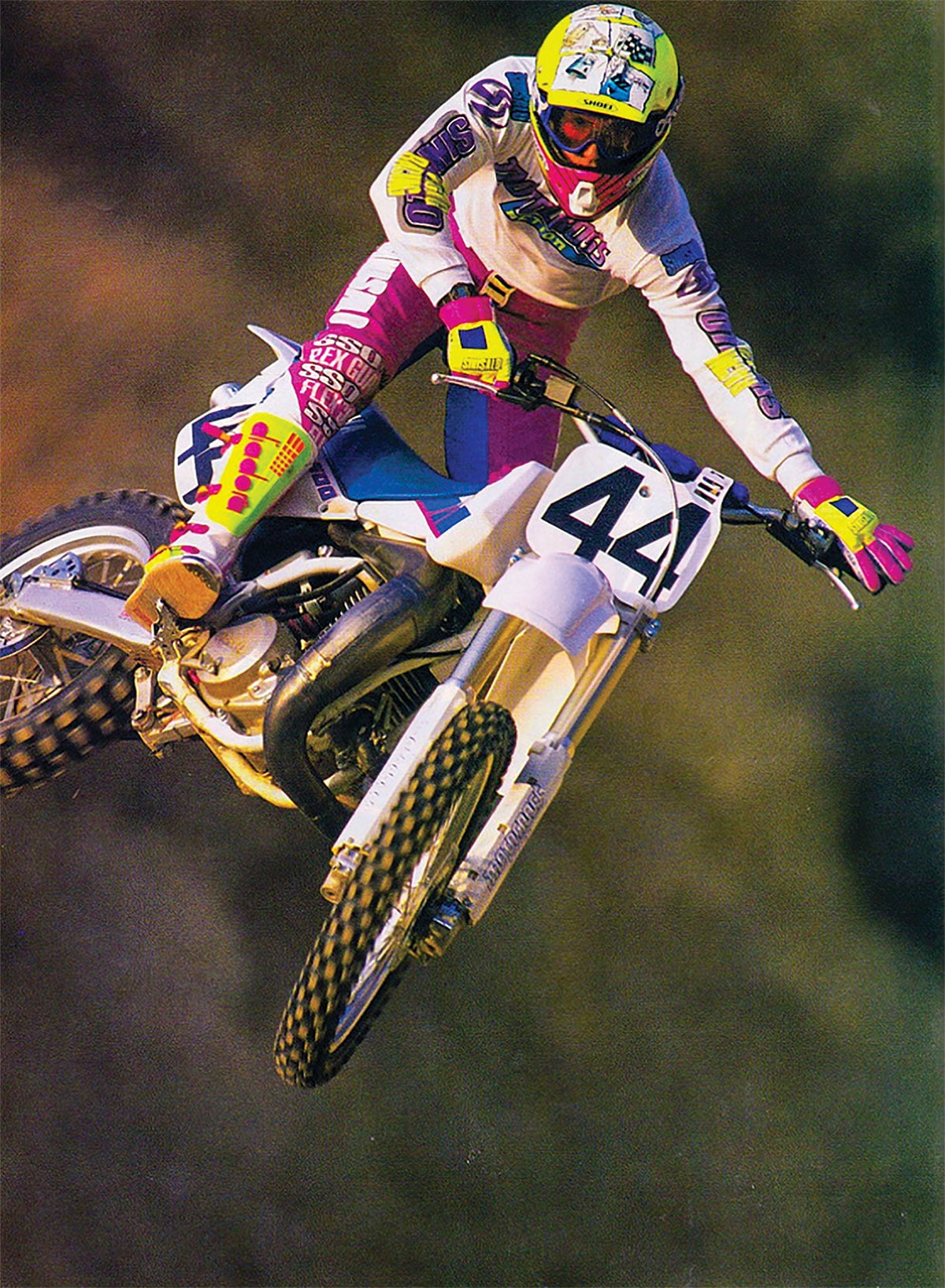

The 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 was whippable.

The 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 was whippable.

(10) Kayaba supplied the front forks for the WR500, but they were not the same forks that came on the 1991 YZ250. Instead, they were a close relative to the 1991 Kawasaki KX250 Kayabas. That’s a good thing, because it meant that with some minor re-valving they could be made to work as well as the KX250’s award-winning forks. In stock trim, the WR500 fork and shock had lighter spring rates than the much-lighter YZ250. The fork spring rate was 0.39 kg/mm, while the shock spring was 4.8 kg/mm. It offered 11.8 inches of front travel and 12.2 inches in the rear. Low-speed damping was exceptionally light, which allowed the WR500 to pick its way through rocks and tight trails, but allowed it to settle deep into its usable travel on a motocross track. To get the forks to ride high enough in their stroke to absorb bumps and jumps required stiffer spring rates and heavier damping.

(11) Since the WR500 wasn’t built from the ground up, development wasn’t started until 1990. Several of the four stages of development (blueprints, proof of concept prototype, pre-pro and production) could be skipped over. By using an existing engine and chassis, the 1991-1/2 WR500 went straight to the pre-production stage (pre-pro). If Yamaha had started from scratch, R&D time would have taken as many as four years.

Jim Holley confirms the ground clearance specs on his WR500 race bike.

Jim Holley confirms the ground clearance specs on his WR500 race bike.

The inherent problem with the 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 had little to do with whether it was a viable off-road motorcycle. It was more that it was built well outside of its time window. It was five years too late. By 1991, it was horse-and-buggy technology trying to compete against the technologically advanced CR500 and KX500. Five years earlier, the WR500 would have been a very good replacement for the aging YZ490. It’s no secret that the YZ490 could have been so much better. The fact that it pinged throughout its lifespan made it a recurring joke in the Open class. It lacked a power valve, even though Yamaha had pioneered power valves. It lacked water cooling. It lacked sleekness. It lacked a classic Open-bike powerband, preferring to be revved more than torqued. It resisted any jetting changes. It had a drum rear brake, and since its introduction as a 1982 model, it had seen only a handful of positive changes.

THE INHERENT PROBLEM WITH THE 1991-1/2 YAMAHA WR500 HAD LITTLE TO DO WITH WHETHER IT WAS A VIABLE OFF-ROAD MOTORCYCLE. IT WAS MORE THAT IT WAS BUILT WELL OUTSIDE OF ITS TIME

WINDOW. IT WAS FIVE YEARS TOO LATE.

Yet, the WR500, which underwent little more than a cut-and-paste R&D program, solved most of those problems without the high-powered budget constraints of the typical new model. The WR500 solved the pinging problem with a lightly milled head. The ponderous YZ490 issue was eliminated by using an up-to-date YZ250 chassis. The powerband was moved down with a new pipe and porting. The weak drum rear brake benefited from the YZ250 frame’s stock rear disc. Yamaha’s benign neglect and do-nothing approach to the YZ490 was in sharp contrast to its do-something approach on the WR500. Yamaha’s engineers and the guys on the “second floor” should have implemented the WR500 strategy way before they did. Sadly, the WR500’s steps forward were too late to erase the YZ490’s “Air Hammer” reputation.

In MXA’s 1991-1/2 Yamaha WR500 test, our final words were, “Anyone who was interested in becoming a serious, hardcore, gung-ho, Open-class motocross racer wouldn’t be satisfied with the multi-purpose WR500. They’d be much better off on one of the purpose-built 500cc motocross bikes. On the other hand, if you are looking for a bike to go trail riding on during holidays, ride in the occasional enduro, and still be able to show up at a local motocross and spin some laps, then the WR500 might work for you.” It wasn’t too little too late; it was just too late.

Comments are closed.