JODY’S TEST RIDER CHRONICLES: MY LIFE AS AN MXA TEST RIDER

The first motocross boom was fueled by the children of the men who fought in World War II. Jody’s father flew 25 missions over Germany in a B-17.

BY JODY WEISEL

I don’t suppose that there is anything especially unique about me that would lead to my Darwinian selection as a motorcycle test rider, except for one thing! By an accident of birth and serendipitous timing, I was born into a glorious age of excess, rebellion and, most of all, the formative birth of risk sports. Thanks to genes and modern medical advances, I have managed to live in the limelight longer than my test rider brethren from the same era.

You’ve probably heard the term “baby boom” before, but never knew where the phrase came from. 77 years ago, American sweethearts put their lives on hold for four long years (from 1941 to 1945) to rid the world of evil. The gals, barely out of bobby sox, kept the home fires burning, while their guys slogged their way across Iwo Jima, Anzio and thousands of filthy little battlefields without names. As for my father, he flew a Boeing B-17 out of Ridgewell, England, to bomb ball bearing factories, ship yards and munitions dumps in Germany. Once the WWII signing ceremonies on the deck of the Mighty Mo concluded, eight million fighting men came flooding back to the heartland…home to their personal Rosie the Riveters.

Nine months later, the “Baby Boom” started. During the first 12 months after the war, kids were popping out at the rate of 338,000 a month, and doctors delivered 3.4 million children in 1946. By 1947 that number had increased by one million babies more. And, from 1954 on, four million little boomers appeared in swaddling cloth each year—peaking at 4.3 million in 1957. At my house, my brother came first, born exactly nine months to the day from when my B-17 pilot dad came home after VJ day.

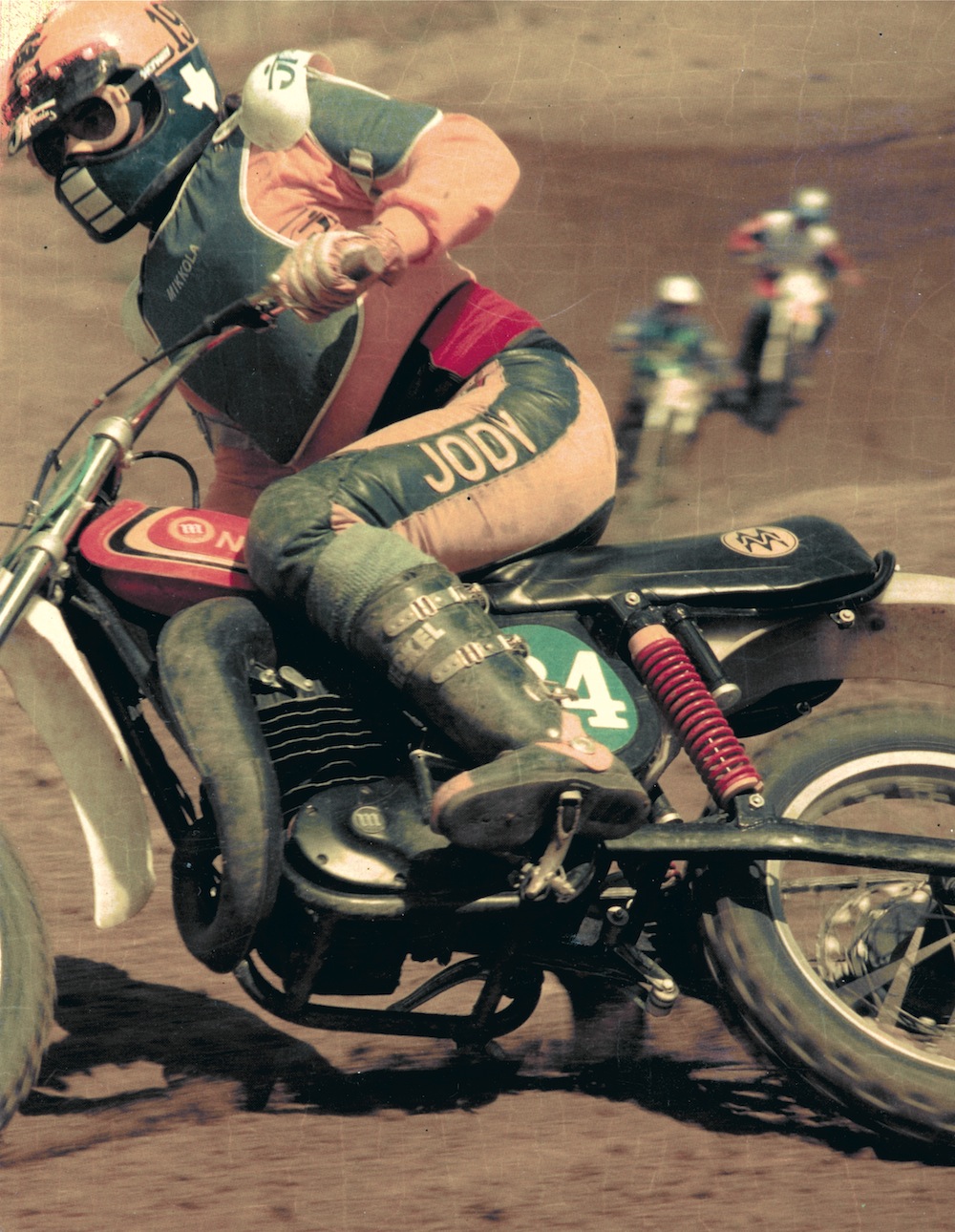

There was nothing cooler in 1974 than riding a Maico. It was the ultimate in German worksmanship, and status came with Maico ownership. Jody hammers a Lake Whitney berm.

There was nothing cooler in 1974 than riding a Maico. It was the ultimate in German worksmanship, and status came with Maico ownership. Jody hammers a Lake Whitney berm.

You might think that I would be a little jealous of my brother, having to wait to make my debut at Letterman General Hospital, just below the Golden Gate Bridge, 19 months later. Not so. That year-and-a-half of waiting made all the difference in the world. In all candor, had I been born first, there would have been little chance of me becoming a motocross racer. My older, and only, brother, missed the cusp of what was to be the brave new world of the 1960s. Although less than two years older than me, he grew up as a hot rodder. He was a juvenile delinquent with a ducktail hairdo (what we younger kids called a JD with a DA). He loved all things Elvis, wore black leather jackets, and thought that the twang of Duane Eddy was the sound of the future. But his Blackboard Jungle generation was not mine. I came to adolescence with the Beatles, hippies, microbuses, long hair, Weathermen, Kent State, Selma, Da Nang, Yasgur’s farm, 13th Floor Elevators, surfing and motocross.future.But his Blackboard Jungle generation was not mine. I came to adolescence with the Beatles, hippies, microbuses, long hair, Weathermen, Kent State, Selma, Da Nang, Yasgur’s farm, 13th Floor Elevators, surfing and motocross.

MOTOCROSS IN THE LATE ’60s WAS NOTHING LIKE IT IS TODAY. THERE WEREN’T ANY JAPANESE MOTOCROSS BIKES. ONLY GROWN MEN RACED MOTORCYCLES. KIDS DIDN’T (AND IF A KID TRIED, HE GREW UP FAST).

To honor his father’s service, Jody’s Varga VG-21 carries the “Triangle L” insignia that was on his father’s B-17 back in 1944.

Motocross in the late ’60s was nothing like it is today. It wasn’t mainstream. There wasn’t a race track in every town. There weren’t any Japanese motocross bikes. The minicycle hadn’t been invented (thus, minicycle fathers had yet to plague the planet). Two-strokes were in their infancy. We wore leather pants and open face helmets. Only grown men raced motorcycles, kids didn’t (and if a kid tried, he grew up fast).

Teenagers in the Sixties went looking for thrills. Bred on stick-and-ball sports, they rebelled by seeking out a new genre of sport — one that had never been popular with kids before — the risk sport.

THANKS TO ADOLF HITLER’S EVIL PLANS, I WAS IN THE RIGHT SPOT AT THE RIGHT TIME. RISK SPORTS NEED YOUNG PEOPLE TO THRIVE. THE BABY BOOM WAS A BONANZA FOR MOTORCYCLE SALES.

By late 1975 the motocross world was in transition. It was the end of the line for Old World bikes like CZ, even one with a center-port kit. Jody’s leather pants, Heckel boots and socks over the boots were out of place with his new generation Bell Moto-Star helmet.

By late 1975 the motocross world was in transition. It was the end of the line for Old World bikes like CZ, even one with a center-port kit. Jody’s leather pants, Heckel boots and socks over the boots were out of place with his new generation Bell Moto-Star helmet.

Although risk sports weren’t invented by the Flower Power Generation, what was new was the fervor with which young people sought out adventure. Prior to the Sixties, risk sports were reserved for adults: Maury Rose was 41 when he won the Indy 500 in 1947, Sir Edmund Hillary was 33 when he scaled Mt. Everest in 1953, and Ernest Hemmingway was 34 when he wrote his 1932 bullfighting manifesto “Death in the Afternoon.” And that about covered the gamut of risk sports before the Sixties…race car driving, mountain climbing and bullfighting.

For comparison, I was 16 when I first paddled out to ride the giants at Lunada Bay (at the time the only ridable big wave on the West Coast). I was only a little older when my dad bought me a Puch dirt bike, and not much more than 18 years old when I took the controls of an airplane for the first time. I wasn’t unusual — just a small part of a big movement that has led to a wholesale change in the way sports are looked at and played.

Thanks to Adolf Hitler’s evil plans and my dad’s years away fighting the Big One, I was in the moment; in the right spot at the right time; lucky to be part of the baby boom. Risk sports need young people to thrive. The baby boom was a bonanza for motorcycle sales.

The baby boomers were at the pointy end of the motocross spear. I was never the fastest guy (and what speed I had dissipates as I get older), but I managed to win races and make a name for myself in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Never deluded about my racing prowess (except for its 56-year duration), my window of opportunity was largely a result of being in on the ground floor. In short, I got here because I got there first.

I WAS REALISTIC ABOUT MY CHANCES OF MAKING A LIVING AS A PRO RACER, BY 1973 I HAD REACHED THE “PETER PRINCIPLE” (AND MY INNER VOICE WAS TELLING ME, “YOU AIN’T GOT IT KID!”)

This is how you turned a Montesa back in the day —pitch it into the turn, let the rear end step out and drag your inside footpeg to control the slide.

Unlike a lot of my competitors, I was realistic about my chances of making a living as a Pro racer (in truth, making a living racing motocross wasn’t a career choice in 1968). To my way of thinking, by 1973 I had reached the “Peter Principle” (in that I had risen as high as I could with what speed I had, and to spend more time chasing it would only reveal my incompetence). That is a major epiphany for any Pro athlete. It is your inner voice telling you, “You ain’t got it kid!” But what to do about it? No words of wisdom from my inner voice were forthcoming. Every athlete, in every sport, must answer this question at some point.

Luckily, I wasn’t hurting for options. All my eggs weren’t in one basket. I had gone to college throughout my racing career and would eventually work my way through the Bachelors, Masters and Doctor of Philosophy regime. I was destined to become a college professor, but fate intervened. Just like today, magazines and media outlets needed someone to ride the bikes for their test photos. Marvin Foster, an exec at Hodaka Motorcycles in Athena, Oregon, suggested me to Cycle News as an experienced motocross racer who was a good test rider. Cycle News‘ Richard Creed, one of the world’s greatest motocross photographers, called me and asked if I would test bikes for them.

It was a lark. It gave me a chance to thrash someone else’s bikes for a change. But, I didn’t like what the Cycle News editors wrote about the bikes that I rode for them. They never rode them themselves, they just asked me questions. I gave them what I thought were insightful answers, and they wrote fairy tales that had nothing to do with what I said. It was frustrating that they sugar-coated everything I said.

I HAD FOUND THE GOLDEN FLEECE; I WAS RACING, BUT GETTING PAID WHETHER I WON OR LOST. IT WAS THE PERFECT COP-OUT.

The look was what attracted young kids to come from behind the snow fence that held the spectators back to join the fun on the track.

The solution came to me during a tedious college lecture on gerontology. Why not just write the test reports myself and cut out the middleman? After all, they were watering everything I told them down anyway. Surprisingly, Richard Creed thought it was a great idea. I suppose in retrospect it was a sweet deal for them, since I was doing their job for free.

But free was not the case for long. This was the formative age of Japanese motorcycles, and the Japanese are nothing if not thorough. They wanted to know everything there was to know about American motocrossers, and there were plenty of test riding opportunities. I had found the Golden Fleece; I was racing, but getting paid whether I won or lost (and I could justify losing by the fact that I was riding a bike that I wasn’t familiar with). It was the perfect cop-out. Subsequent to the day I quit racing Hodakas, I never rode the same bike for longer than one month. More often than not, I raced a different bike in every moto. I tested parts for lots of companies — shocks, tires, reed valves, carbs and anything that could be bolted on a bike.

In 1975, Cycle News editor Richard Creed called and said that they needed people who actually raced motocross on their staff. I agreed to join them, but only if they let me follow the complete Trans-AMA Series before reporting to work. They said okay and picked up the tab for the greatest ten weeks in my young life. I didn’t stay at Cycle News for very long, but I had fun. Within my first year, I had offers to work as a test editor at Cycle, Cycle World, Cycle Guide, Popular Cycling, Dirt Bike and a very small magazine called Motocross Action.

No suspense. I chose Motocross Action because it was about what I did. No fluff. No headlights. No speedometers. No posers (at least back in the day). It was all about motocross and only about motocross. I was no spring chicken at this point. I had started racing motocross in 1968 on a Sachs, spent several years campaigning Hodakas and CZs, did two years of test rider gigs, worked at Cycle News from 1975 to 1976, and went to work at MXA on January 3, 1977. I’ll do the math for you — I’ve been at MXA for 47 years. It’s a record of some kind for something that nobody keeps records of.

I USED TO TEST BY RIDING AS FAST AS I COULD. EVENTUALLY, I CRASHED OR THE BIKE BROKE. NO BIG DEAL; BREAKING AND CRASHING WERE AN EVERYDAY PART OF LIFE WITH THE MACHINERY OF THE 1970s.

In his young days Jody had a single-minded approach to test riding—it involved crashing a lot. This not how you test motocross bikes, this is how you test knee ligaments.

To this day, I still race every weekend. And just like five decades ago, I never race the same bike for longer than one month. And more often than not, I race a different bike in every moto. In the last 50 years I have ridden virtually every motocross bike made, including most of the worthwhile works bikes and more roaches than a case of Raid could kill. The list is impressive (not in small part because it dates back to the early 1970s).

In the 1970s, production bikes didn’t have very many tuning possibilities. There were no clickers on the shocks or forks, and you just rode them as they came out of the crate. I used to test a CZ, Bultaco, Maico, BSA, Ossa, Montesa or Carabela by riding it as fast as I could. If that didn’t tell me anything, I rode it faster. Eventually, I rode it so hard that I crashed or it broke. No big deal; breaking and crashing were an everyday part of life with the agricultural machinery of the 1970s.

I might have kept on with my flat-out approach to testing except for a run-in with Jeff Smith. I raced the two-time 500 World Champion at Saddleback in the Vet Master class, and when I passed him on the first lap I felt like I had reached the pinnacle of my racing life. It didn’t last long. A lap later, the BSA factory rider, 13 years my elder, wound it up and went by me at twice my speed. He disappeared from my view in short order. After the race, Jeff sat me down and said, “Jody, don’t try to go so fast. Take your time and build your speed. You have to slow down to go really fast.”

I absorbed Jeff’s comments and realized that what counts in a test rider is the ability to have a deft touch, to feel the bike and to eliminate himself from the equation. As a strict science, the only way to test motorcycles is as blindly as possible and with as much paperwork as humanly feasible. Shrugs, grunts and “it’s okay” comments are not acceptable. Engineers (and those writing consumer reports) need hard facts, spiced with words that have meaning. It’s not just the quality of the test rider that builds better motorcycles, or gives buyers a fighting chance at selecting the best one, but the rigorous examination that the test rider undergoes after spending time on a new bike.

Flat-out speed in a test rider only makes him valuable as a race team test rider, where he is working on settings for the select and chosen few. The average rider isn’t fast and if forced to race Roczen’s, Tomac’s or Barcia’s bike would realize that what these men do and the machines they do it on have nothing in common with the rest of us. The worst test rider for a production motorcycle is a fast AMA Pro who still thinks he’s fast. A test rider has to think about, not just the performance of the machine, but the end user as well.

THE THEORY THAT DRIVES THE MEEK, WHO INHERIT MANY TEST POSITIONS AT MAGAZINES, IS THAT IF THEY DON’T SAY ANYTHING BAD, THEN NOBODY WILL BE OFFENDED.

They don’t all make it through every test. Jody contemplates shooting the 1979 Yamaha YZ125F to put it out of its misery at Saddleback. A blown main bearing was the culprit this time, but it has been everything from broken frames to exploded hubs.

I have written lots of scorched earth bike test. Not surprisingly, most test riders have decided that it isn’t worth the risk to write bad things, so they shy away from saying factual things about bad bikes. Not MXA. We called a garbage scow a “garbage scow” when it deserves it. On the other hand, a rave review means that the test rider believes that the factory is on the right track and wants the engineers (or the consumer) to know how much they like the way the bike performs. Sometimes, bikes that aren’t all that special get praised, but at least you have to admire the test rider’s misplaced passion.

If an engineer makes a really good product, he doesn’t want his bike’s superiority to be diluted by a less-than-stellar competitor getting a good review by a timid test rider or one who is paid by his competition. And, surprisingly, if the engineer is part of a project that makes a bad product, he doesn’t want the powers-that-be back at the factory to believe what they read in the “speak-no-evil” test as blanket approval of the bike — and a reason to cut funding for a new version

“I DON’T CARE IF YOU’RE RIGHT OR WRONG, AS LONG AS YOU ARE ALWAYS RIGHT OR ALWAYS WRONG. BUT YOU CAN’T BE A GOOD TEST RIDER IF YOU ARE ONLY RIGHT HALF THE TIME.” ED SCHEIDLER.

Even with its soft rear suspension, vicious understeer and Spanish reliability, Jody loved his 1977 wrinkle-fin Montesa 250VB. He called it “a guilty pleasure.”

I’m not the world’s greatest test rider. I’m not the worst either, but I can tell you the names of all the bad test riders on three sheets of paper (single-spaced and double-sided), and even the ones who sell out for a side gig from a manufacturer. Meanwhile, the names of the good test riders would fit on a postage stamp. I pride myself on being consistent. I know what makes a good motorcycle, and I can identify those traits every time I ride a bike (I’ve had 50 years of practice to get it right). Consistency is very important — but that consistency can only be proven via experience.

One day, when I was testing YZs with Yamaha’s most famous test engineer, Ed Scheidler, he told me something profound about being a test rider. “I don’t care if you’re right or wrong, as long as you are always right or always wrong. But you can’t be a good test rider if you are only right half the time.”

Ed and I didn’t always see eye-to-eye on testing. He would often send me out to test a part, only to find me back in the pits 15 seconds later, claiming that the mod was no good. “How do you know if it was better or worse? You didn’t even do a full lap?” he’d bellow as I climbed off the bike.

“I don’t need a full lap when it’s so far off. In fact, I wanted to turn around on my way through the pits, but I gave you one corner out of courtesy,” I replied.

“Just put your seat in the saddle and do what I tell you,” he’d snap back.

“DYNOS CONFIRM WHEN THE ENGINE BUILDER IS ON THE RIGHT TRACK, EXCEPT FOR WHEN HE IS ON THE WRONG TRACK.”

Every MXA test rider has been hurt at some point in his career. One word of advice; if you are going to crash like this, you might want to wear a chest protector and ditch the French-made Techno helmet.

MXA dynos all of its test bikes, sometimes we report the numbers and sometimes we don’t. Why and why not? A dyno number doesn’t tell you anything of importance, you still have to ride the bike—and lots of dyno queens are flat-out roaches. However, there are two kinds of dynos at a test rider’s beck and call and only one requires strapping a bike to a machine. Mitch Payton once told me that, “Dynos confirm when the engine builder is on the right track, except for when he is on the wrong track.”

The “human dyno” is Ed Scheidler’s seat in the saddle example. If you ride enough different bikes, and you have ridden the model that came before the one you’re testing (and the one that came before it, ad infinitum), you eventually hone your senses to feel fast from slow (or more accurately faster from slower). But this is pseudo science. As much as I trust senses that have done nothing but accelerate and decelerate for over 50 years, I know that they can be fooled, much like your depth perception in Knott’s Berry Farm’s tilted house. Cross referencing, by going back and forth between bikes, is a must.

You would think that a guy who raced some of the most famous vintage bikes of today, back when they were new, would be into vintage racing, but Jody says that he didn’t want to race his 1974 Super Combat In 1975, so why would he want to race it in 2024.

Conversely, the “dirt dyno” has been my mainstay for all these decades. Unlike most test riders, I prefer to test by racing. Why? Because only in a race will I push to the limits of my now meager speed. Only at a race will I hit bumps that could be avoided on a practice day. Only at a race will I ask more of myself and thus more of the machine than I would on a Tuesday. For most of the ’70s and ’80s, I tested at the famous Saddleback Park. I rode there thousands of times and, because of that, I could accurately predict my lap times without a stop watch. I knew to the millisecond if the bike I was testing was laying down tracks or just laying down and dying.

But bikes can’t always be tested on MXA’s turf. Bikes don’t always come to meet-and-greet us on our home turf. MXA has tested bikes in Holland, France, Japan, Germany, Sweden, Austria, Italy, Canada, Mexico, England and Finland. With no dirt dyno and no Dynojet, the human senses are all we have to rely on — that and each other. Although I started out as a Lone Ranger in the early ’70s, over the years I was aided, supported and often guided by MXA’s cadre of test riders: Pete Maly, Ketchup Cox, Clark Jones, Bill Keefe, Lance Moorewood, Larry Brooks, David Gerig, Ed Arnet, Zapata Espinoza, Gary Jones, Alan Olson, Willy Musgrave, Tim Olson, John Minert, John Basher, Dennis Stapleton, Josh Mosiman and Daryl Ecklund.

IF I COULD ONLY PICK ONE BIKE TO RACE, IT WOULD BE THE 1981 MAICO 490. IT CORNERED LIKE A 125, RAN LIKE THE SUPER CHIEF, AND OOZED COTTAGE INDUSTRY CHARM.

Jody on his favorite bike of all-time —the 1981 Maico 490 Mega 2.

People often ask me what my favorite bike is (or was). I hem and haw for a minute before admitting that I do have favorite bikes—bikes that after I tested them, after they faded into obscurity and after they were obsolete, I still remembered them fondly. They would not be every one’s favorites—but, they were mine. If I could only pick one bike to race (in its time), it would have to be the 1981 Maico 490 Mega 2. It needed shock help, relaced wheels and arc’ed brakes, but this bike was luscious to ride. It cornered like a 125, ran like the Super Chief, and oozed cottage industry charm.

You have to go way back to have raced in rubber tank commander goggles—never mind the sideburns and Hallman GP chest protector.

I loved the late ’60s and early ’70s Hodaka Super Rats. They sold for peanuts, ran like a clock and could be rebuilt in 20 minutes. This bike was the linchpin of the dirt bike craze in the USA. In 1978, in their dying days, Hodaka offered me the chance to prototype a motocross version of the Hodaka 250ED. The budget was miniscule, but the finished project was pretty good (although it used a potpourri of parts from other brands and aftermarket companies). Unfortunately, once I finished the test cycles, Hodaka asked me to send the Thunderdog back to Athena for analysis. It has never been seen since.

Horst Leitner’s KTM 125 no-link prototype.

Another bike that I was lucky enough to ride before it disappeared was Horst Leitner’s KTM single-shock, no-link, prototype. In 1989, the then-KTM management asked the ATK inventor to build them the bike of the future. In his Laguna Beach factory, Horst designed a super radical KTM prototype. It used a no-link rear shock, single-sided radiator, exhaust pipe that exited downward behind the engine, and a three-tube hanger-frame. Although the project was supposed to be a secret, Horst let the MXA wrecking crew race the bike at Perris Raceway before crating it up for the trip to the Austrian R&D department. Good thing he did, because the bike disappeared, never to see the light of day again until in 2019 when an Austrian engineer realized that he had the one-off machine in his garage.

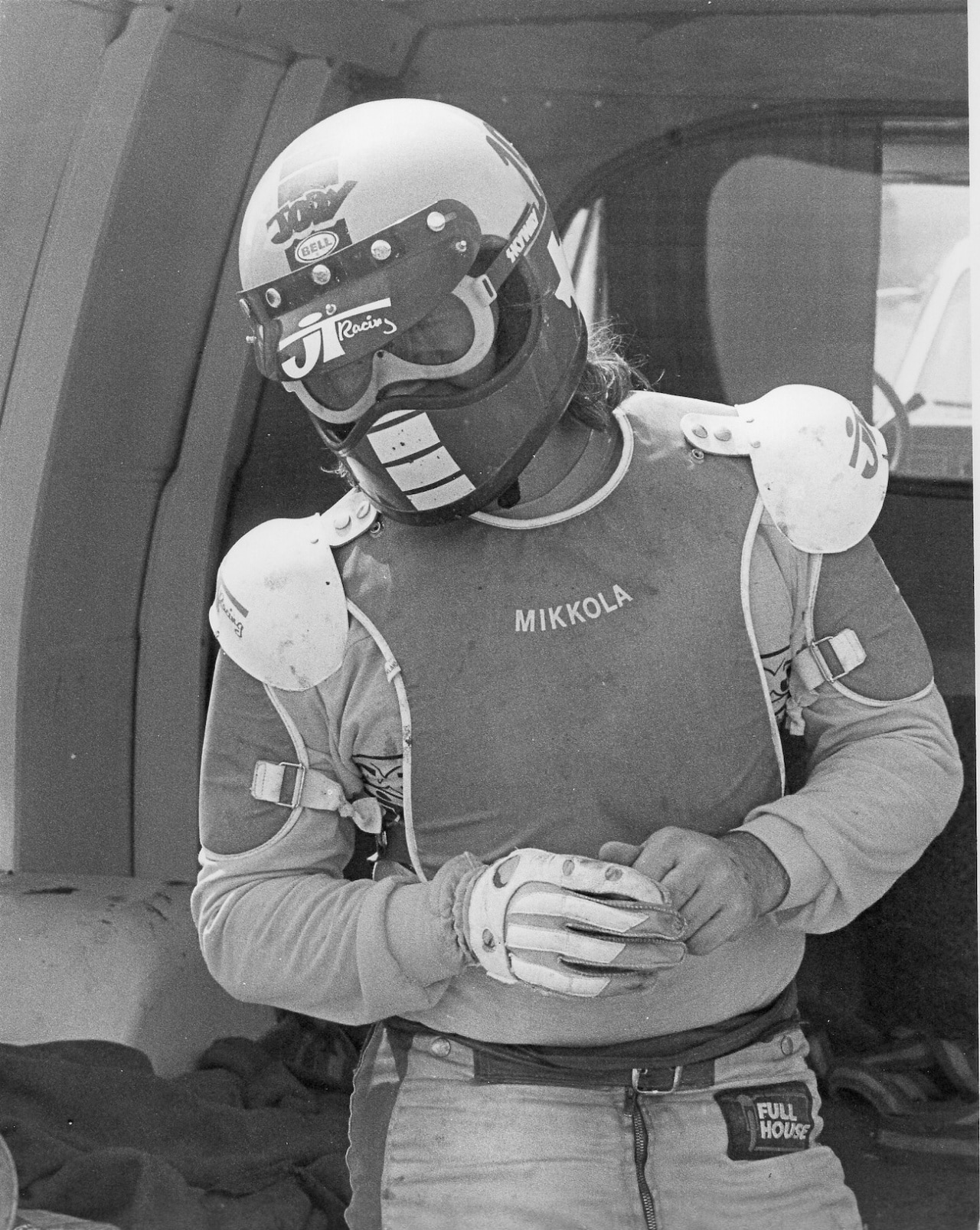

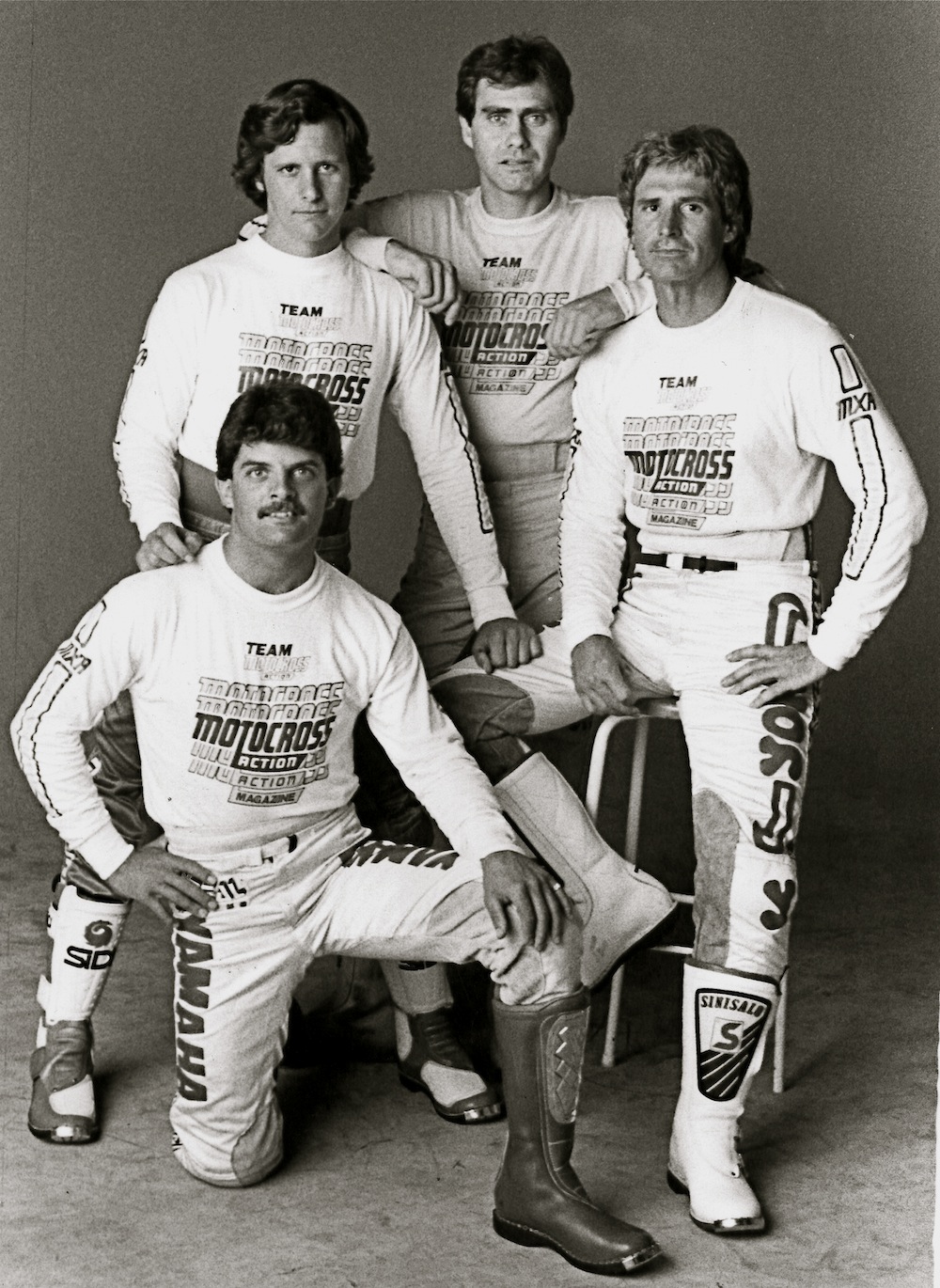

The MXA wrecking crew circa 1985. (Front row) Lance Moorewoodand Jody Weisel. (Back row) David Gerig, Gary Jonesl.

I’m older now than I was when Hodaka exec Marv Foster recommended me as a test rider so many decades ago. I like to think that I’m wiser, although I must admit that most of the know-how in my vast reservoir of worthless knowledge was achieved through osmosis. When I first started racing, I reveled in my ignorance. Not knowing what was going on was bliss, because there was nothing I could do about it anyway. My MX IQ increased as a direct result of the sheer number of bikes I rode, tech briefings I attended and smart people I associated with.

Jody, last weekend at Glen Helen. He has piled up thousands of motos since 1968.

As a matter of political correctness, I’d love to claim that the years spent working on my Bachelors, Masters and PhD. were the keys to my success, and that every aspiring motorcycle test rider would do well to hit the books, stay in school and get a degree (or three). Perhaps in the world of Air Force test pilots, an engineering degree is a must, but for a motorcycle test rider, nothing beats an educated derriere — Ed Scheidler’s “seat in the saddle.”

The measure of a test rider isn’t defined by the coolness factor of being the first to ride a new bike, nor the fact that so few people are chosen to do the job (and some that do should be fired immediately). In function, test riders are worker ants who do their jobs virtually alone, on empty tracks with no one around to admire their handiwork. It is a job, not an adventure. When a test rider does his job right, either in the employ of a manufacturer or as the ombudsman of the consumer, he is an anonymous public servant. If he is honest, he serves the public by telling people something that they can’t find out for themselves — except at great cost. Circumstances beyond my control nominated me for the job. I can only hope that I was good at it.

Every man who races a motorcycle is a test rider. You have it in your power to make your motorcycle better or worse — all you have to do is put your seat in the saddle and make some adjustments (and if you start today, you’ll have been testing motocross bikes for as long as I have by 2073). Mark that date on your calendar.

Comments are closed.