JODY’S TRUE STORY OF “LET BROCK BYE”

THAT WAS THE YEAR THAT WAS! EVEN THOUGH IT WAS 1977, THEY ARE STILL LETTING GUYS BY IN 2023

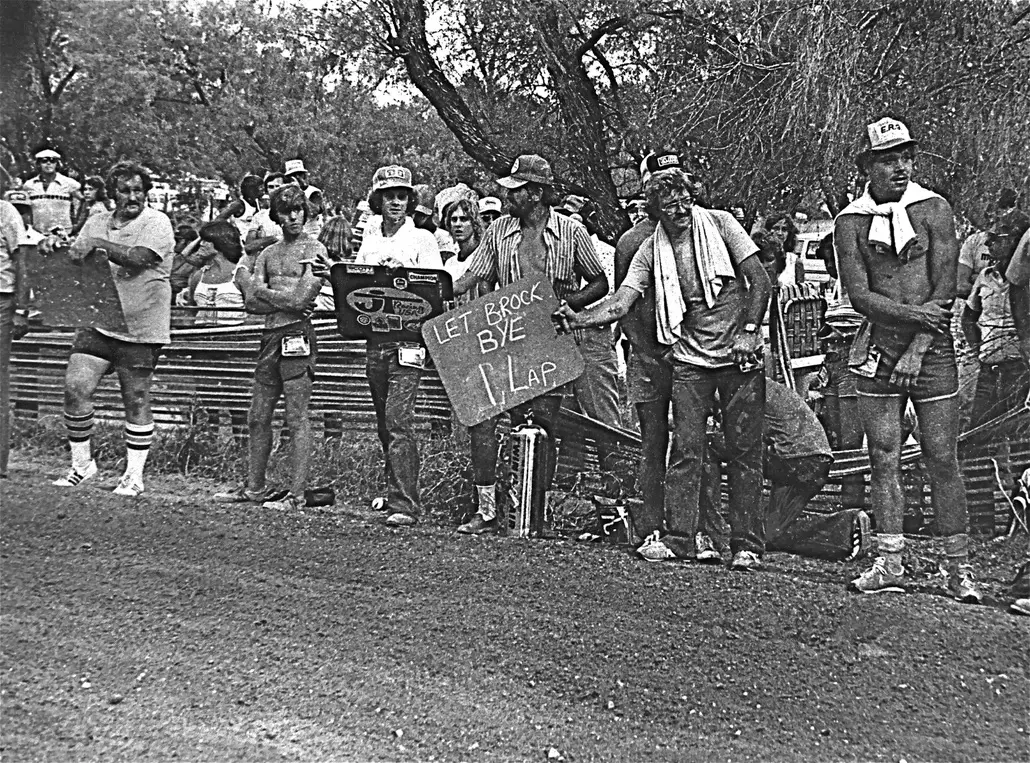

Visible in Jody’s famous photo are Bevo Forti (far left), Dave Osterman (JT pitboard), Don Westfall (beard), Keith McCarty and Leon Wolek (ERG/Gookinaide hat).

Visible in Jody’s famous photo are Bevo Forti (far left), Dave Osterman (JT pitboard), Don Westfall (beard), Keith McCarty and Leon Wolek (ERG/Gookinaide hat).

By Jody Weisel

Forty-sixr years ago, American motocross’s hippie years were about to end. I remember it like it was yesterday. Oh, air-cooled engines, twin-shocks, 428 chains and my long locks would hang on for a few more years, but the camaraderie of the formative years (1968-1976), a time that I like to think of as innocent and spiritual, was about to hit the bridge abutment of commercial prostitution. The head-on impact was so sudden that the old era’s epitaph could be written in just three words — “Let Brock Bye.”

The central character of motocross’s change of life was Bob Hannah. Hannah, who would go on to become the biggest name in American motocross history, was an unlikely hero. Yet, he became grander than everyone who came before or after. The shaggy-haired 20-year-old wandered the pits with a slouching manner, but a powerful presence. He wasn’t all business; he didn’t ride dirty; he wasn’t poetry in motion. In truth, he worshiped at the altar of John Wayne more than Roger DeCoster. He reveled in practical jokes, was quick to laugh, and would do anything for a friend. Yet, he was a juggernaut on the track. He rode with an inner anger that oozed to the surface and was fueled by personal insecurities. Bob Hannah was both a paradox and a palindrome. Rough around the edges in language and manners, he was blessed with sharp business acumen — sharp enough to change the balance of power in motocross from the factory to the rider.

When Hannah went out in practice, the other riders would gather to watch him ride. His style was more eclectic than polished, but the kid had a grip of steel. Half the time he was flapping along behind his bike like a flag in a stiff breeze. His greatest strength as a rider, apart from his tremendous desire to go fast, was his unwillingness to let go of the handlebars no matter how dire the situation.

Hannah’s silencer fell off at Plymouth and jammed into his tire. The drag caused his bike to seize.

FOR HANNAH, THE 1976 VICTORY WAS MORE THAN JUST A TROPHY FOR HIS MANTLE: IT WAS CLASS WARFARE. HANNAH VIEWED THE WORLD AS A BATTLE BETWEEN THE HAVES AND THE HAVE-NOTS.

In 1977, Hannah wasn’t a veteran of the National circuit. He had pocketed only one complete season in 1976 (and two exploratory 125 Nationals in 1975). But, his star had risen quickly, built on the ashes of the former boy wonder of the 125 class, Marty Smith. In 1976, Hannah had focused his fury on Smith in the way that a cat paws at catnip. The Hurricane, as Hannah was nicknamed, had won five of eight 125 Nationals in 1976 to take the title by 87 points over San Diego surfer Marty Smith, the 1974 and 1975 Champion. For Hannah, the 1976 victory was more than just a trophy for his mantle: it was class warfare. Bob saw Marty Smith as the squeaky clean, middle-class teen idol and himself as the scruffy, working-class desert rat. Hannah viewed the world as a battle between the haves and the have-nots.

For the 1977 season, it is often said that Hannah had bitten off more than he could chew. Instead of the Hurricane just trying to back up his 1976 AMA 125 National Championship, Yamaha had him contesting all four title chases. Hannah split his time between the 125 Nationals, 250 Nationals, 500 Nationals and 250 Supercross series. Believe it or not, if it hadn’t been for scheduling conflicts, Hannah might well have pulled off the quadruple. In the end, the AMA feared a Hannah sweep of every Championship so much that they stopped holding single-class Nationals — choosing to combine them on the same day. It was a blatant anti-Hannah move by the AMA, but perhaps the greatest compliment that a sanctioning body could pay a rider.

In the 1977 250 Supercross Championship, Bob won six of ten events and clinched the title in late November at Anaheim Stadium. In the 1977 AMA 250 National Championships, Tony DiStefano won his third straight 250 title, but Hannah did manage to win the Herman, Nebraska, round (and finish seventh overall in the standings). In the 1977 AMA 500 National Championships, Hannah won the Charlotte, North Carolina, round and finished second overall behind archenemy Marty Smith for the title.

Bob had set out to race ten Supercrosses, seven 250 Nationals, six 500 Nationals and six 125 Nationals in a single year. There was only one date conflict (Hangtown was a combined 125/250 National), but all the rest of the races were single displacement Nationals with support classes. Eventually, the stress of trying to win all the classes was brought to a halt by the reality of the enormity of the task at hand. And while Hannah did manage to pull off winning a 125, 250 and 500 National, plus a 250 Supercross in the same season, Team Yamaha finally chose to have Bob focus on the 125 chase for 1977. And what a 125 National Championship series it turned out to be. There were three distinct battle plans at work during the 1977 series — each manned by riders who would go on to greater things in the coming years.

TEAM SUZUKI’S DANNY LAPORTE HAD CHAMPIONSHIP SPEED, BUT WAS PARADOXICALLY HAMPERED IN THE TITLE CHASE BY THE FACT THAT HE HAD A DECENT POINTS LEAD BY THE END OF THE FIRST TWO ROUNDS.

Broc won the 1977 125cc title because he won one more race than Danny LaPorte, but the deciding race he won was the San Antonio race that Bob Hannah took a dive in.

First, there was Bob Hannah. Hannah was riding with more than his usual derring-do. Next came Broc Glover, Hannah’s Yamaha teammate, but by no means his friend. Broc was in his first year at Team Yamaha. He couldn’t afford to ride with Hannah’s blitzkrieg style. He wanted to keep his job, and failure to finish would be the kiss of death. Finally, Team Suzuki’s Danny LaPorte had Championship speed, but was paradoxically hampered in the title chase by the fact that he had a decent points lead by the end of the first two rounds. From race three on, Danny tried to ride cautiously — willing to give up points as long as he had them to give. But not willing to crash in defense of points.

The 1977 AMA 125 National Championship series was six races long. Here is how it played out.

PLYMOUTH, CALIFORNIA:

Bob Hannah had a do-or-die approach to every race he entered, and his maniacal riding style was made all the more furious by the fact that he only earned three points at the opening round in Plymouth, California (the original Hangtown track). Yamaha had been scared out of running their water-cooled engines (by the claiming rule) and chose to go with a non-water-cooled version of the OW27 works bike. In moto one, Hannah was leading when his muffler fell off and wedged into his rear tire. The drag predictably led to a seized engine that Bob miraculously nursed home to 17th. In moto two, Bob’s chain guide broke and he threw his chain. Danny LaPorte went 1-1 at Plymouth, and privateers Pat Richter, Gary Ogden and Steve Wise kept all the other factory riders at bay. Hangtown gave LaPorte a massive lead over Glover (8th) and Hannah (17th).

KEITHSBURG, ILLINOIS:

The Keithsburg race was held at Sandy Oaks Raceway; a sand track that proved to be one of the roughest and toughest tracks of the year. On the whooped-out track, Bob Hannah owned the day. LaPorte would go 2-4 for second, while Broc Glover went 8-2 for third. Danny’s second place in the first moto came at the expense of 500cc rider Jimmy Weinert, who was racing his first-ever 125 National at Keithsburg. The Jammer was running second until his experimental KX125 ran out of gas. Weinert didn’t start the second moto because Kawasaki didn’t have a big enough gas tank capacity to get him to the checkered flag. LaPorte stretched his lead on Glover at round two, and while he lost ten points to Hannah, Danny still had 37 points in hand over the Hurricane.

MIDLAND, MICHIGAN:

Midland was another sandy track, and it was also a coup for the Yamaha duo of Hannah (1-2) and Glover (5-1). Jimmy Weinert was back with a bigger gas tank and took his KX125 to third overall (2-4) in front of Danny LaPorte’s 4-3. LaPorte’s results may seem decent, but in fact he had a devastating day. It was a day that would haunt him by season’s end. In the second moto, Danny was running second behind Broc Glover when a spectator darted across the track and hooked Danny’s brake cable. Danny kept his bike upright, but his drum brake cable was bowed out. Hannah quickly caught up to Danny and a battle royale ensued. Unfortunately for Danny, at the very end of the moto, the brake cable flexed inward, caught on the front knobs and threw Danny over the bars. Hannah was gone and so was second place. Danny remounted in time to keep third, but those two lost points would be telling in San Antonio.

BOB WENT TO THE STARTING LINE OF THE FIRST MOTO WITHOUT A CLEAR PICTURE IN HIS HEAD OF WHERE THE TRACK WENT. IN THE END, BOB WENT RIGHT WHEN THE TRACK WENT LEFT.

Team Yamaha moved every rider out of their respective classes and put them in the 125

class in San Antonio. Rick Burgett, Bob Hannah, team manager Kenny Clark, Broc Glover,

Mike Bell and Pierre Karsmakers were all there.

RIO BRAVO, TEXAS:

Shocker! Hannah didn’t win. Broc Glover was perfect in the Houston suburbs and easily won both motos. Local Texas hero Steve Wise was equally good with a 2-2 day. Danny LaPorte was a safe and sane third overall with a 4-4. As for the Hurricane, he struggled to a 5-5 day. Why? Bob had engine trouble in the morning and completely missed practice. He spent all of practice watching his engine being rebuilt. Bob went to the starting line of the first moto without a clear picture in his head of where the track went. In the end, Bob went right when the track went left and he collided with another rider. He remounted in tenth and worked his way back to fifth by moto’s end.

Glover’s easy day was aided in the second moto when Danny LaPorte and Japanese Suzuki teammate Koji Masuda crashed into each other off the start. LaPorte charged through the pack to get back to fourth (he even passed Bob Hannah). Hannah wasn’t as lucky. He fell down after an altercation with Jimmy Weinert and ended up tailing Glover, Wise, Weinert and LaPorte home.

ST. JOSEPH, MISSOURI:

LaPorte’s conservative strategy was failing him, as was Bob Hannah’s total war approach to the series. At St. Joe’s Hannah took both moto wins (he raced like he had no choice but to win), while Glover went 3-2 for second in front of Warren Reid (5-3), Danny LaPorte (4-4) and a new kid, Mark Barnett (2-8). With one round left, LaPorte’s massive early lead had been whittled down to ten points over Glover and 17 points in front of Hannah. Bob had won three of the five 125 Nationals to this point, but mechanical issues had cost him any chance of winning the title with only San Antonio left on the calendar.

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS:

For me, getting to fly from SoCal to San Antonio was a homecoming. I had graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School in San Antonio and, at that time, my parents still lived in the Alamo City. I got to sleep in my old bedroom and get up and go to the races just like when I was a kid. I’m not going to lie to you, I had my favorites going into the San Antonio race. I had been buddies with Texan Steve Wise since the early days at Lockhart, Lake Whitney, Mosier Valley and Forest Glades. During the 1977 season I had hung with Pat Richter throughout the 125 Nationals and always liked Danny LaPorte as a person (and still do).

IT SHOULD BE NOTED THAT AT THIS POINT IN HIS CAREER, BROC GLOVER WASN’T THE POMPOUS HORSE’S PATOOT HE WOULD BECOME ONCE HE ACHIEVED STARDOM.

Hannah hated what he had to do in San Antonio and says that he walked into the Yamaha offices on Monday morning he demanded the Championship bonus.

It should be noted that at this point in his career, Broc Glover wasn’t the pompous horse’s patoot he would become once he achieved stardom. Broc was still a naive San Diego kid, happy to be on a works bike and enjoying life. He wasn’t snide, overtly smug or egotistical…yet. I say those terrible things about Broc because that is what he became in the ’80s. Today, much old and wiser, Broc’s personality is now closer to the 17-year-old Broc than the 24-year old “Golden Boy” that he believed himself to be at the height of his Yamaha stardom. In short, I was rooting for Danny LaPorte. There was no need to root for Bob Hannah — he didn’t need my support or anyone else. He was a force of nature.

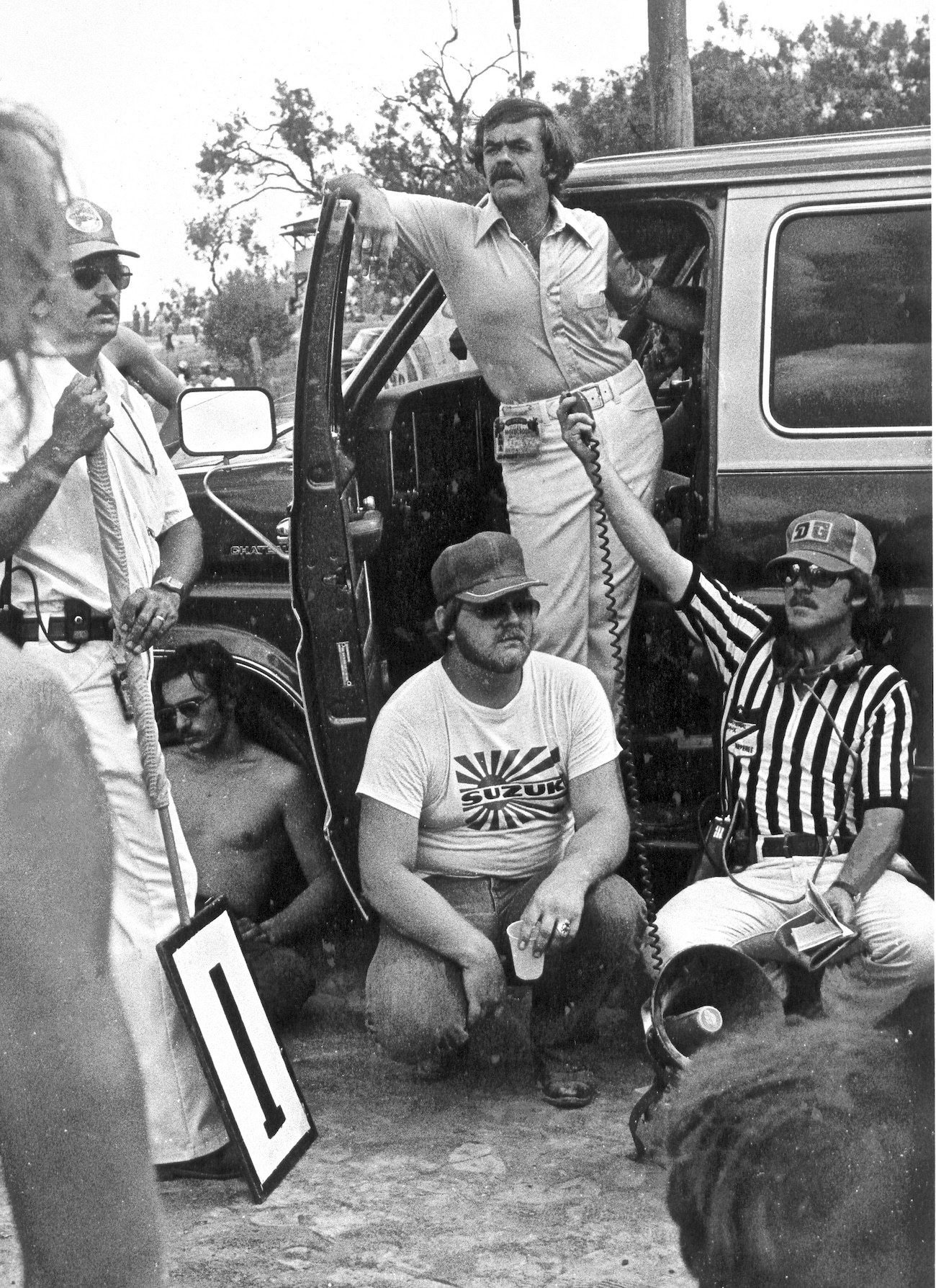

San Antonio’s Cyclerama track was a pile on the day of the National. The pits were located in what looked like an abandoned quarter-mile oval track and it was a very muggy and hot August 14th. Typical weather for South Texas in late summer. There was, to quote Sherlock Holmes, “foul play afoot” in San Antonio. Instead of the normal two factory Yamaha riders in the 125 class, Yamaha team manager Kenny Clark had drafted Pierre Karsmakers, Rick Burgett and Mike Bell to get in the way of Danny LaPorte. AMA referee Mike DiPrete took one look at the entry list, flew to San Antonio and called a riders meeting to admonish the riders about interfering with others riders on the track…and as he spoke he looked directly at Karsmakers, Bell and Burgett.

Big-bike specialists Karsmakers and Burgett didn’t want to be there. Pierre left no doubt when he pulled me aside after the riders meeting and said, “I’m not here to block for anyone, least of all for Hannah and Glover. I plan to stay as far away from the front as possible.” Mike Bell was in a more ticklish situation. San Antonio was his first real chance to show Team Yamaha what he could do. He wanted to try to win, but he knew that wasn’t in the cards. He had to walk a delicate line between serious racer and Snidely Whiplash.

The only rider in the 1977 San Antonio National who knew was was going on was Bob Hannah. Danny Laporte (above) didn’t find out what happened until after the race was over.

The racing in San Antonio wasn’t especially noteworthy. The Moto-X Fox team of Steve Wise and Pat Richter holeshot the first moto, but the AMA decided that both orange-and-yellow riders had jumped the gate. Richter, Ryan Villopoto’s uncle, crashed out and Wise was penalized ten places (from fifth to 15th).

Broc Glover won moto one with Bob Hannah in second and Danny LaPorte in third. With one moto to go in the season, the points difference was now five points between LaPorte and Glover (the difference between first and third).

SPORTING SCANDALS AND RIGGED EVENTS HAVE BEEN THE BANE OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS SINCE THE FIRST BOOKIE TOOK A BET ON PHEIDIPPIDES AT THE BATTLE OF MARATHON IN 490 BC.

Jim Weinert was a player in the 1977 AMA 125 National Championships, but he was really on a busman’s holiday.

Before we move on to the controversial outcome of the second moto, let me say a few words about historical precedent. Sporting scandals and rigged events have been the bane of professional sports since the first bookie took a bet on Pheidippides at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. In more modern times, ever since Shoeless Joe Jackson and his 1919 Chicago White Sox teammates threw the World Series at the request of gamblers (earning them the Black Sox name), the idea of rigging the outcome of an event has been considered a criminal offense against the fans. In the 1960s, NFL players Alex Karras, later a TV sitcom star, and Paul Hornung were suspended from football for one year for betting on the outcome of games. In the ’70s Pete Rose was racking up baseball records, but before his career was over he would be barred from entering Cooperstown for betting on sports games (games that the Commissioner of Baseball believed he had some control over).

And, in 1974, the Russians sent out a series of hitmen to make sure that Czech rider Jaroslav Falta did not win the 250 World Championship. Russian Guennady Moisseev won the crown, but there were enough incidents between Falta and Moisseev’s red star teammates to cause the title to be tainted. Now, in 1977, the AMA faced its first serious issue about fixing the outcome of a Pro race. Not only had Yamaha packed the field with potential blockers, whose reason for being there could only be construed as trying to interfere with Danny LaPorte’s progress, but Yamaha eventually altered the outcome of the race by ordering Bob Hannah to take a dive.

As the second moto wore on, with Bob Hannah a good 25 seconds ahead of Broc Glover and a distant Danny LaPorte in third, it was obvious to anyone who could do the math that LaPorte was going to be the 1977 AMA 125 National Champion. As the laps counted down, I wandered back towards the pits, stopping to talk to my buddy Jim “The Greek” Gianatsis just across the track from the mechanic’s area. There were no photos left to shoot, as the race had taken on the monotony of a Shriner’s Parade. As the Greek and I chatted about where we would go to dinner, our cameras hung harmlessly by our sides. The Greek scribbled in his notebook for the story he was working on for MXA and I watched the mechanics across the way. I could see Bevo Forti, Dave Osterman, Keith McCarty and ERG’s Leon Wolek standing inside the orange nylon fence.

Neither the Greek nor I have any idea why we suddenly snapped to attention and shouldered our Nikons. We just reacted instantly as Bob’s mechanic, Keith McCarty, held out a pit board that had “Let Brock Bye” written on it. I fired my shutter and turned to the Greek and said, “Did you see that?”

THE PIT BOARD, RIFE WITH MISSPELLINGS, HAD DISAPPEARED AS RAPIDLY AS IT HAD APPEARED. BY THE TIME I LOOKED BACK OVER, MCCARTY WAS FURIOUSLY ERASING WHAT HE HAD WRITTEN.

Steve Wise (12) was on the Fox team in 1977. He and teammate Pat Richter holeshot San Antonio, but the AMA penalized them.

The pit board, rife with misspellings, had disappeared as rapidly as it had appeared. By the time I looked back over, McCarty was furiously erasing what he had written. What happened next could only have been written by Rod Serling as an episode of The Twilight Zone. Bob Hannah slowed to a crawl and Broc Glover caught and passed him in one lap. That pass gave Broc Glover three more points and suddenly Broc and Danny LaPorte were tied for the National Championship…and based on moto finishes throughout the series, Broc was going to be the 1977 125 National Champion.

I hustled across the track to get back to the Yamaha pits before Broc and Bob. The only problem was that Bob Hannah didn’t stop in the pits. He rode straight through the quarter-mile dirt oval and kept right on going out into the woods. And he didn’t come back.

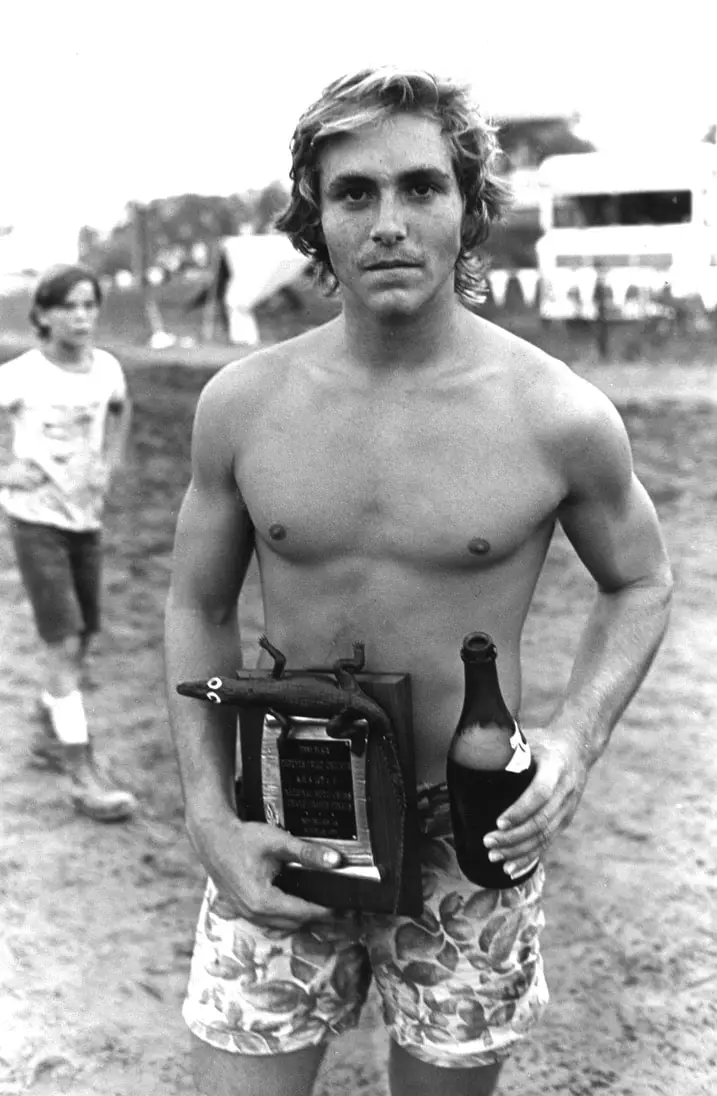

Broc rolled into the pits and was embraced by mechanic Jim Felt. Broc was happy, smiling and oblivious to what had just occurred. Broc was thrilled to have won the 125 National Championship. Later Broc would say, “I vividly remember going by a bike on the last lap and asking myself, ‘Did that bike have a number one on it?’ I would have liked to have had a moment to go up to Bob and thank him for what he did, but I didn’t get the chance because Bob was nowhere to be found. It was a bittersweet victory and I still hear about that day 46 years later.”

Broc may have been ecstatic, but no one else at Team Yamaha was happy. They all looked guilty, confused and apprehensive. The mood was strange. It was a melancholy mix of suppressed anger and subdued happiness. The vibe was all wrong for the moment. And I must admit that I wasn’t aware of the ramifications of what had taken place. Caught up in the moment I hadn’t put the pit board, Hannah’s weird exit and the gloomy atmosphere together. Like everyone else in the pits, I just assumed that it was the culmination of a long day.

It wasn’t until later that I realized that of all the people at Cyclerama that day only Keith McCarty, Bob Hannah, Jim Gianatsis and I had seen the pit board. The vast majority of fans in San Antonio believed that Broc Glover had legitimately won the second moto, the overall and the Championship. In truth, they had been duped by racing politics.

I ran into Yamaha team manager Kenny Clark immediately after talking to Broc. I asked Kenny, “How does it feel to win the 125 National Championship for the second straight year?”

He looked at me suspiciously, as he always did, and said, “I have nothing to say.”

I was taken aback. That is not the normal response of a team manager that has just clinched the title — especially not an opinionated one like Ken Clark. So, pressing further I asked, “Are you giving me a ‘no comment’ to that question?”

I was pressing and Kenny looked at me and firmly said, “No comment!”

WHEN BOB CAME RIDING BACK TO THE PITS ALMOST AN HOUR AFTER THE RACE WAS OVER, HE LOCKED HIMSELF IN THE FRONT OF THE YAMAHA BOX VAN AND WOULDN’T COME OUT. IT WAS OBVIOUS TO ME THAT HE HAD BEEN CRYING.

Danny Laporte and Bob Hannah were friends. Bob Hannah and Broc Glover were not. That is Keith McCarty holding the infamous pit board over Hannah’s head in the background.

Danny Laporte and Bob Hannah were friends. Bob Hannah and Broc Glover were not. That is Keith McCarty holding the infamous pit board over Hannah’s head in the background.

I was stunned by Clark’s comments, but not for long. Clark’s weird answer triggered my thought processes into overdrive. And the longer I waited for Bob Hannah to come out of the woods, the more incredulous I got about what was going on. When Bob came riding back to the pits almost an hour after the race was over, he locked himself into the front of the Yamaha box van and wouldn’t come out. It was obvious to me that he had been crying.

Suddenly, all of the pieces of the puzzle began to fit. I felt like I had deciphered the Dead Sea Scrolls. Something was rotten in Denmark (or at the very least in San Antonio). When I got back to SoCal the next day, I developed the San Antonio film in my own darkroom. When I saw the “Let Brock Bye” photo, I called the AMA and said that I was pretty sure that what Team Yamaha had done in San Antonio was a violation of rules 3(b), 3(h) and 3(j) of Chapter 13 of the 1977 AMA rule book. By arranging for the outcome of the race to be altered, Team Yamaha had conspired to rig the results. Yamaha had forced Hannah, in boxing jargon, to take a dive. AMA rules stated that “abetting or knowingly engaging in any meet in which the result is fixed” is illegal. And so is “engaging in any unfair practice, misbehavior or action detrimental to the sport of motorcycling in general.”

THE AMA SAID THAT THEY HAD CALLED YAMAHA TEAM MANAGER KENNY CLARK TO DISCUSS THE ISSUE, BUT HE DIDN’T RETURN ANY OF THEIR CALLS. I ASSUME THAT JOHN DILLINGER NEVER RETURNED ANY PHONES CALLS FROM J. EDGAR HOOVER EITHER.

At first the AMA told me that no such rules existed, but when I insisted that it was written in black and white, they told me that it was “a stupid rule and shouldn’t be in the book.” They were trying to make this issue go away and, in typical AMA fashion, they didn’t want anything to do with the rule book or enforcing the rules. I still had a trump card and when I told the AMA that I had a photo proving that Team Yamaha ordered Bob Hannah to throw the race (and in effect fix the outcome of the event and the Championship), they begrudgingly told me that they would look into it. At least that’s what they said, but, they didn’t really want to look at it. When questioned about why they were dragging their feet, the AMA said that they had called Yamaha team manager Kenny Clark to discuss the issue, but he didn’t return any of their calls. I assume that John Dillinger never returned any phones calls from J. Edgar Hoover either.

The whole issue wasn’t moving forward very fast and Yamaha’s initial reaction to the fact that they were being investigated for possible violation of rules 3(b), 3(h) and 3(j) was that they had done nothing “new” and that fixing the outcome of races was standard operating procedure. The only difference in this case was that the public had become aware of the team orders because of my photo. Public pressure and the light of day was not something that Yamaha wanted. And they held off on any advertising touting their victory to await the outcome of the investigation. They feared backlash.

FUTURE PRECEDENT WAS BEING SET, AND IF THE RULES WERE NOT ENFORCED IN THIS CASE THEN HOW COULD THE FANS OR RACERS EVER BELIEVE THAT THE RULES WOULD BE ENFORCED BY THE AMA IN THE FUTURE?

The AMA’s Mike DiPrete tried to lay down the law at the riders meeting in San Antonio.

The AMA’s Mike DiPrete tried to lay down the law at the riders meeting in San Antonio.

As for Team Suzuki, they were as frozen in place as Yamaha and the AMA. They did not pursue the matter with a vengeance — even after the photo was shown to them. Suzuki did eventually send a letter to the AMA contending that Yamaha violated the rules. And, more pertinently, it pointed out that the public trust in racing and the racers was at stake in this issue. Future precedent was being set and if the rules were not enforced in this case, then how could the fans or racers ever believe that the rules would be enforced by the AMA in the future? Suzuki’s contention is almost eerie, in light of the fact that the AMA rule book has never been enforced with any consistency from that day forward — unless privateers were the culprits.

The AMA for their part could not claim ignorance. AMA referee Mike DiPrete came to the race on a special trip. He read the rule book at the riders meeting for the first time in AMA history. And he obliquely warned Team Yamaha not to engage in any funny business. Amazingly, after the race, the AMA played dumb and contended that they had no reason to suspect any foul play in San Antonio. Almost one month after the San Antonio race, with the 1977 AMA 125 National Championship still in limbo, AMA Commissioner of Racing Douglas A.J. Mockett handed down his decision on the violation of rule 3(b), 3(h) and 3(j). It read:

For the AMA, the San Antonio affair was over. They claimed that motocross was a “team sport” and that the teams were free to do as they pleased with the outcome of a race — which came as a surprise to the 30 privateers on the line who weren’t part of any team.

For Broc Glover, Danny LaPorte and Bob Hannah, the incident has never ended. Later Bob would say, “Danny LaPorte was a guy that I couldn’t dislike if I tried and here I was riding against him for the 1977 AMA 125 Championship. And I had to let a guy that I don’t like, and never have, Glover, by to beat my buddy. I knew that I had to let him by, but I’ll tell you this, on Monday morning I went to Yamaha and told them that they had to pay me the Championship bonus for letting Broc by. They cut me a check.”

I CONSIDER BROC TO BE AN INNOCENT VICTIM OF THE BIG BUSINESS OF PROFESSIONAL RACING, BUT I AM NOT SYMPATHETIC TO HIS PLAINTIVE REQUESTS THAT I BURN THE NEGATIVE.

The whole affair soured me against AMA incompetence, the unhealthy influence of the manufacturers and the stupidity of almost every powerful person I dealt with during my journey to get to the bottom of what really happened…and should have been done about it. The photo, the undeniable evidence, is the only reason that anyone in the world knows the words, “Let Brock Bye.” Apart from my own use, I’ve never abused the photo, taken any money for its rights, given it to TV shows, video producers, other websites or magazines—if you have seen it any other place than MXA, it was stolen.

The events of that day are still a sore subject four decades later — especially with Broc. I consider Broc to be an innocent victim of the big business of professional racing, but I am not sympathetic to his plaintive requests over the decades that I burn the negative to my “Let Brock Bye” photograph. Yamaha won the 125 Championship that day, but with all the negative publicity they probably wish that they hadn’t. All five of the Yamaha riders that were in San Antonio that day would end up in the AMA record books — for much more than their contributions to that single day in Texas. Maybe by the standards of today’s jaded racing, lax rules enforcement, clueless AMA direction and ethical numbness, the events of August 14, 1977, don’t seem so sinister to the average fan, but their frame of reference has been skewed by 46 years of AMA ineptness, factory team manipulations and the weaker morals of modern times.

Unlike today’s mercenary riders, back in 1977, motocrossers believed that they were living by the code of sportsmanship. Riders respected each other, the fans venerated (instead of eviscerated) them and the ethos of the time was one of brotherhood. Maybe my vision has been blurred by the passing of four decades, but to me, the original values of the sport were destroyed by that pit board. And it is the writing on the pit board that matters — not what actually occurred on the track. If Yamaha had developed a code and had written “Plan Nine From Outer Space” on the pit board, there would have been no issue. Why not? Because the evil hand of the corporate executives would not have been so evident. The true issue has always been about the alleged conspiracy to cheat the public out of a fair race and the specter of corporate interference in the honesty of the sport.

That was the last day of innocence for the sport of motocross. It was no longer purely a man against man endeavor, but a corporation against corporation shell game (in which the peas of the strongest team could be shuffled to alter the outcome at the will of the board of directors). Today, the sport likes to think of itself as growing rapidly, supporting a huge industry in its wake and as being a major motorsports player. We are constantly pitched the concept that modern motocross is in its golden era, but greedy agents, cheating teams, callous executives and inept administrators do not a better sport make.

The real trick, for those interested in racing, is to forget about today and remember that 46 years ago, one day before August 14, 1977, motocross was a very different sport.

Comments are closed.