LONG & WINDING ROAD: HISTORY OF THE HUSQVARNA AUTOMATIC

BY JODY WEISEL

How would you like to hop on your motocrosser and never have to pull the clutch in, never shift a gear, and never worry about downshifting, upshifting, clutch slipping or gear selection? If only someone made an automatic motocross bike, it would cut the time it takes to learn how to ride in half. Perhaps in the all-electric future will find out if that’s true.

The Husqvarna Auto was just that machine. But, it is important to note that it was never intended to be a motocross bike. Not even close. The first prototypes were built in 1973 for a competition between Husqvarna, Monark and Hagglunds to build the best military-spec off-road bike for the Swedish Army. The required features were a 100-watt quartz lighting system, low-operating noise levels, the ability to run while laying on its side and a gearbox that could be fixed in the field (with tools from the supplied toolkit). But, most of all, the army was looking for a motorcycle that they could teach a raw recruit to ride in less than a week. And, they were offering a government contract to the brand that made the best machine.

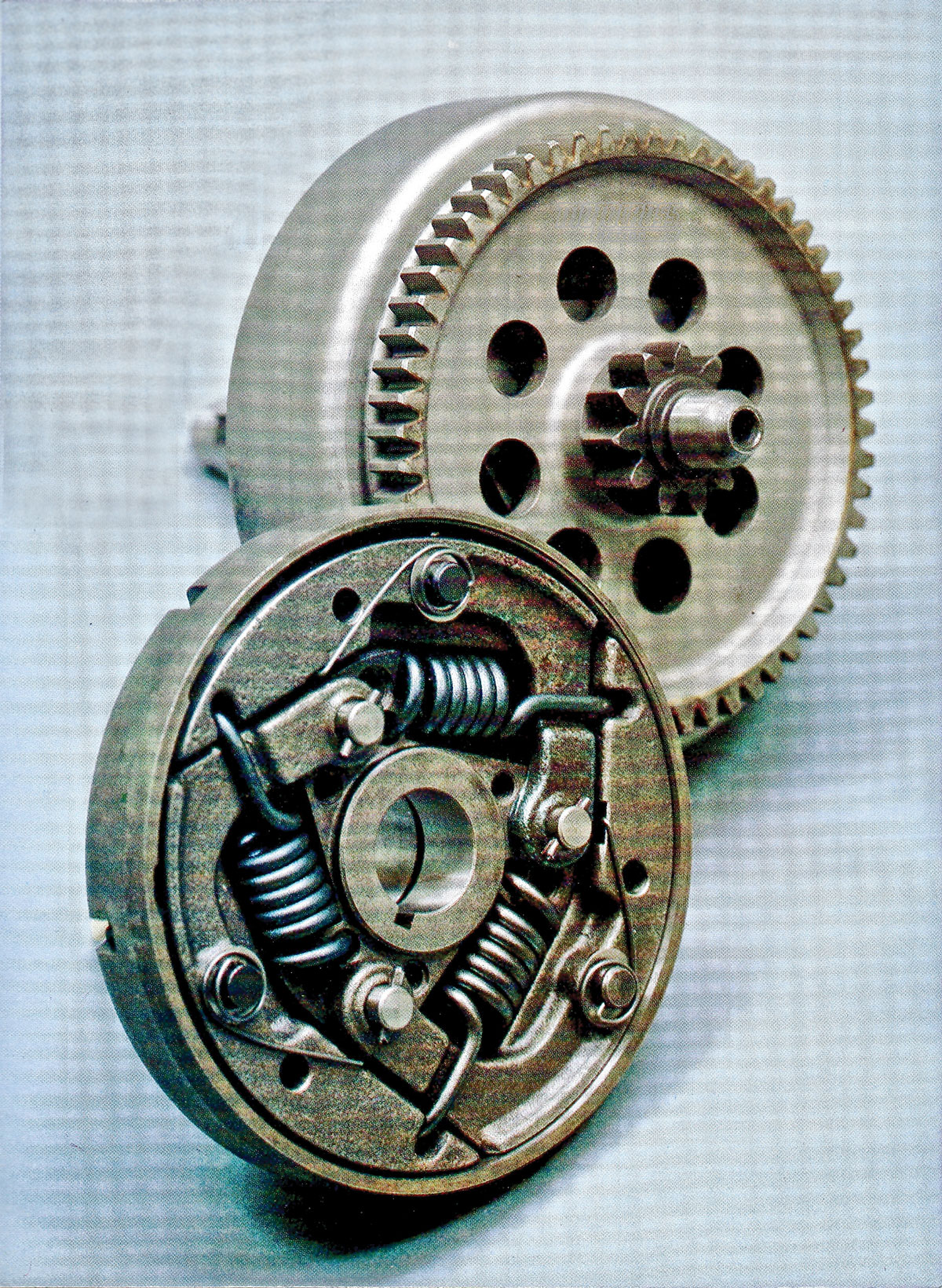

AS THE MECHANISM SPINS FASTER AND FASTER, THE SHOES ARE FLUNG OUTWARDS UNTIL THEY MAKE CONTACT WITH THE HUB. THIS IS WHY A CENTRIFUGAL CLUTCH IS OFTEN REFERRED TO AS A “SLINGER CLUTCH.”

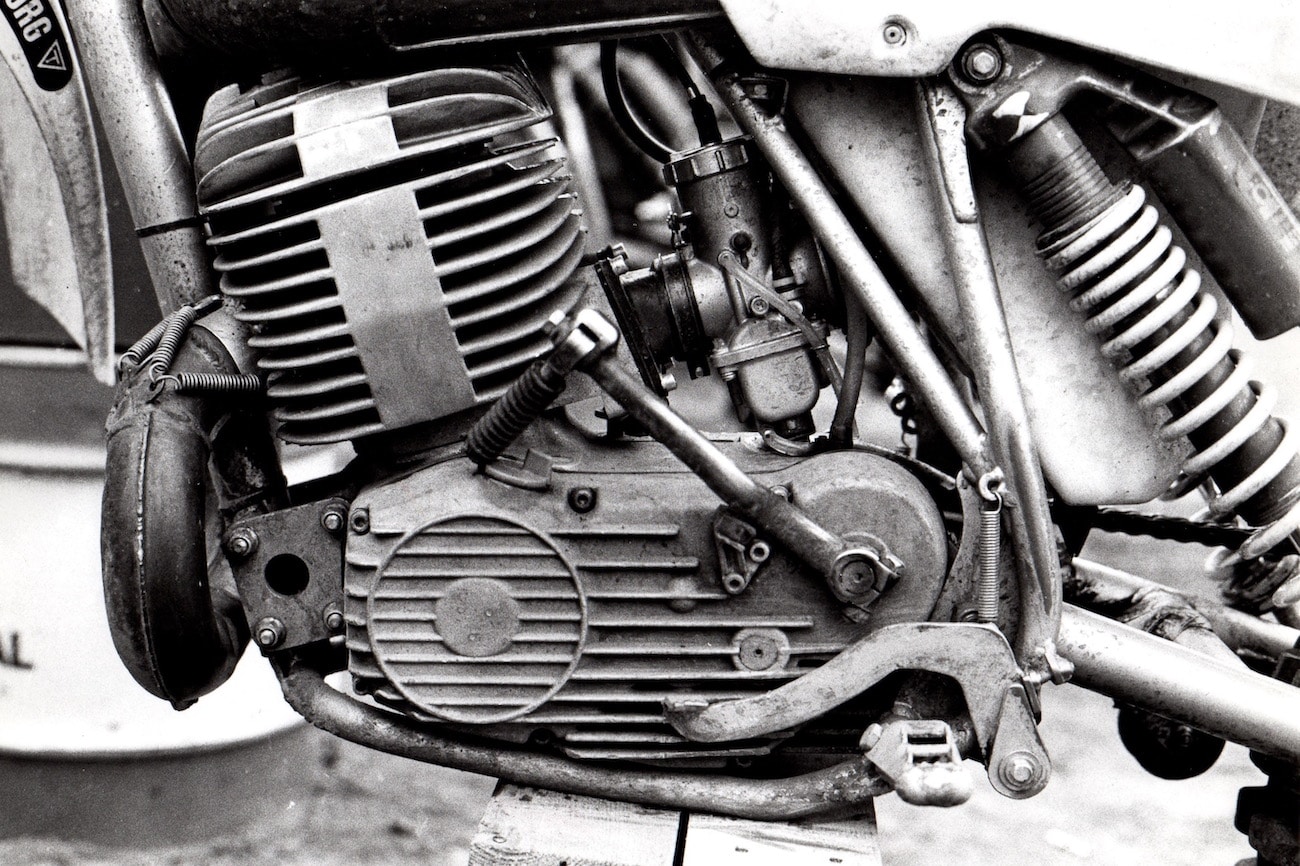

The best thing about the 1978 Husqvarna 390AF—and all Husky Autos—was that the automatic engine fit perfectly in the stock frame, with the only visible difference being the lack of a shift or clutch lever.

The best thing about the 1978 Husqvarna 390AF—and all Husky Autos—was that the automatic engine fit perfectly in the stock frame, with the only visible difference being the lack of a shift or clutch lever.

The Swedish military establishment wanted a bike that anyone could ride, was trouble-free, was quiet and freed a soldier’s hands—at least one—for more serious work. The three-speed Husqvarna 250 Autos were perfect for the utilitarian functions of military scouting, courier work and map making, but, ironically, the Hagglunds XM72 snowmobile engine-powered monocoque bike won the Army contract. Unfortunately, Hagglunds had issues putting its prototype into production and withdrew from the competition. Thus, by default, Husqvarna got the Army contract and set out to build 3300 units for what would turn out to be a very lucrative, long-term deal. Husqvarna had designed the highest-quality product possible by tossing out the tired ideas that held back all previous automatics. They discarded the torque converter concept used on bikes like the Rokon and Hagglunds and the hydrostatic hydraulic systems that used pressurized oil to select gears. Husqvarna looked for a simple solution, and engineer Lars-Erik Gustausson was the man who applied advanced technology to make it work.

The radical Hagglunds XM72 bike won the Swedish Army contract, but to Husky’s surprise, Hagglunds couldn’t fill the Army order and handed the contract to Husqvarna. Note The XM72’s one-sided leading-link forks, stamped monocoque frame, gas tank in the frame, one-sided swingarm, mag wheels and disc brakes.

The radical Hagglunds XM72 bike won the Swedish Army contract, but to Husky’s surprise, Hagglunds couldn’t fill the Army order and handed the contract to Husqvarna. Note The XM72’s one-sided leading-link forks, stamped monocoque frame, gas tank in the frame, one-sided swingarm, mag wheels and disc brakes.

With a high-dollar Swedish Army contract for 3300 military motorcycles hanging in the balance, Husqvarna started the automatic transmission project in 1973 with no thoughts of selling the bikes to consumers.

With a high-dollar Swedish Army contract for 3300 military motorcycles hanging in the balance, Husqvarna started the automatic transmission project in 1973 with no thoughts of selling the bikes to consumers.

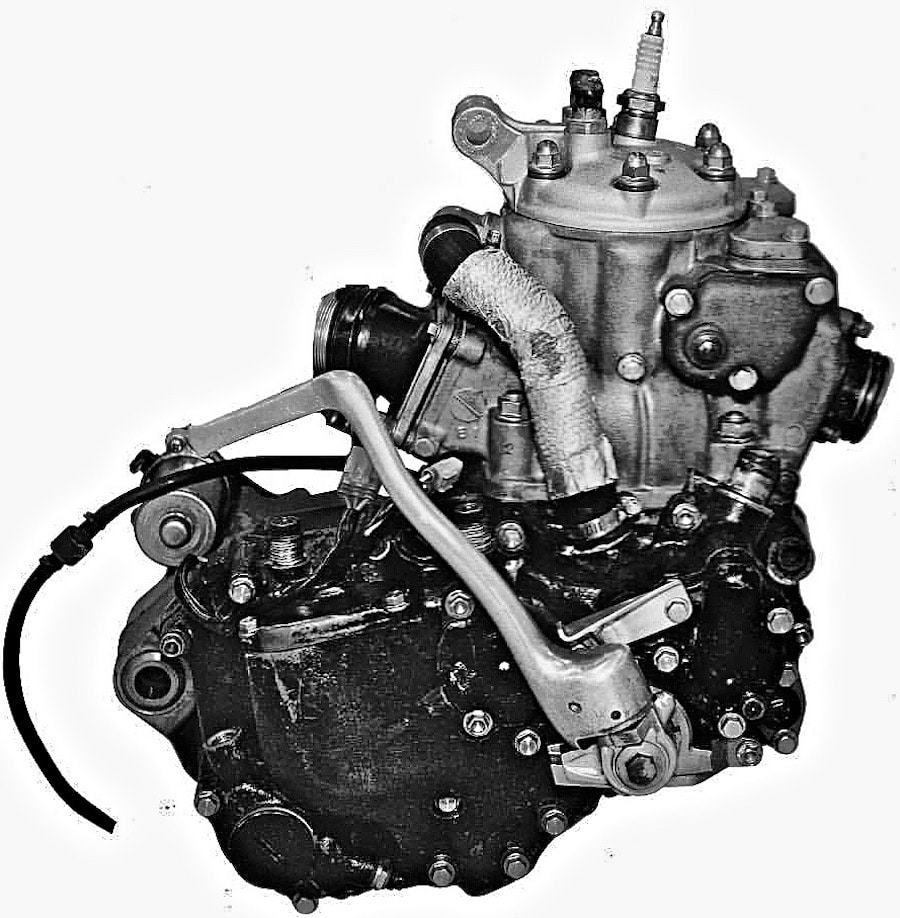

Providing the key link to Husqvarna’s automatic connection is the centrifugal clutch, which Gustausson borrowed from the chainsaw division. Centrifugal clutches are what make the ubiquitous mopeds and Pee-Wee motocross bikes move. In essence, a centrifugal clutch is similar to a set of drum brakes. The clutch plates are shaped like brake shoes, and the clutch hub is the drum. Instead of the drum spinning, as on a car wheel, the shoes spin inside the hub. The shoes do not touch the hub at low rpm, but as the mechanism spins faster and faster, the shoes are flung outwards at approximately 2500 rpm until they make contact with the hub. This is why a centrifugal clutch is often referred to as a “slinger clutch.” When the shoes grab hold of the drum, the bike moves. Friction caused by the shoes dragging against the hub meshes the spinning brake shoes with the hub, which turns the rpm into motion. Unlike a brake shoe that drags on the hub to stop a bike, the Husqvarna clutch shoes spin outwards to engage the gears.

SITTING IN THE PITS, THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A HUSQVARNA AUTO AND A STANDARD 6-SPEED HUSKY. THE MISSING SHIFT AND CLUTCH LEVER ARE THE ONLY OUTWARD SIGNS THAT SOMETHING SPECIAL IS HAPPENING.

The engine castings were high quality, and the cylinder had ample finning. The only irritating thing about the Husqvarna Autos was the left-side kickstarter, which meant that most riders had to stand beside the bike to start it.

The engine castings were high quality, and the cylinder had ample finning. The only irritating thing about the Husqvarna Autos was the left-side kickstarter, which meant that most riders had to stand beside the bike to start it.

There are four gears housed inside the Husqvarna automatic transmission. The three-speed version was dropped when the bike went into production as a consumer product. First gear is a basic slinger clutch. You rev the engine up until the clutch shoes spin outward enough to grab hold of the hub. First gear uses 43-psi clutch springs that enable the Auto to calmly idle without trying to take off. As the rpm climb with throttle input, the centrifugal forces overcome the 42-psi spring tension and first gear is engaged. From that point on, each gear’s centrifugal clutch kicks in as the rpm rises.

A very clever and intricate gearbox operates off of the power supplied by the slinger clutches. The result is a bike that shifts through the gears by itself. Once you dial the throttle open, the Husky Auto moves forward until it reaches the correct speed to shift to second gear. Second, third and fourth gears are engaged by a series of very complicated sprag gears and large-diameter dog-bone bearings that engage in one direction and release in the other. It upshifts as long as you keep the throttle on and downshifts by freewheeling when you shut the throttle off—until you turn the throttle back on. At this point, it chooses the gear that is best mated to the speed of the rear wheel. It upshifts and downshifts by itself, but a savvy rider could manipulate the throttle and brakes to get the Auto to shift more precisely.

For those who have ever ridden a Rokon torque converter, the specter of weight, width and bulkiness are nonexistent on a Husky Auto. In fact, the engine is almost identical in dimension to a normal Husky, save for the lack of a shift or clutch lever. The engine fits in the production Husqvarna chassis and weighs only 6 pounds more than the stock 6-speed 390CR engine.

HUSKY AUTO RACERS OFTEN SAID THAT WHEN THEY CHOPPED THE THROTTLE, IT FELT LIKE THE HUSKY ACCELERATED TOWARDS THE CORNER INSTEAD OF SLOWING DOWN.

Husqvarna’s slinger centrifugal clutch.

Husqvarna’s slinger centrifugal clutch.

Sitting in the pits, there is no difference between a Husqvarna Auto and a standard 6-speed Husky. The missing shift and clutch lever are the only outward signs that something special is happening. To start the Husqvarna Automatic, you reach down with your left hand and flip the neutral/drive lever on top of the cases to “neutral.” Then, push the choke lever down on the Mikuni carb and give the kickstarter a healthy boot. Kicking the engine hard with your right leg while standing to the left of the left-side kickstarter will normally bring it to life in two kicks. It must start when you kick it over, because there is no such thing as bump-starting a Husqvarna automatic transmission.

In neutral, the engine can be revved up, cleaned out and warmed up to operating temperature. When you are ready to ride the Auto, you let the rpm drop down to a smooth idle and flip the lever from “neutral” to “drive.” Be forewarned that there is a small amount of lash when you engage the centrifugal clutch for first gear. If the idle is set properly, the bike will not jump forward or try to take off. You can sit and talk to the guy next to you on the starting line with the bike in “drive” as long as you don’t rev the engine above 2500 rpm. Once in “drive” the bike will move when you turn the throttle enough to overcome the 42-psi spring that holds the first-gear clutch shoes back.

Because there is no need to feather the clutch or move a shift lever, the Husky Auto gets off the starting line smoother than bikes with manual foot-operated transmissions. There is no time lost to pilot error. As long as you keep the throttle on, the bike will upshift its way through second, third and fourth gears. Each shift comes with a subtle lunge similar to that on older-model Chevy automatic transmissions.

THE SMALL CADRE OF HUSQVARNA AUTOMATIC MOTOCROSS RACERS HAD TO FIND THEIR OWN SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS. MOST OF THE SOLUTIONS HAD TO BE DISCOVERED THE HARD WAY.

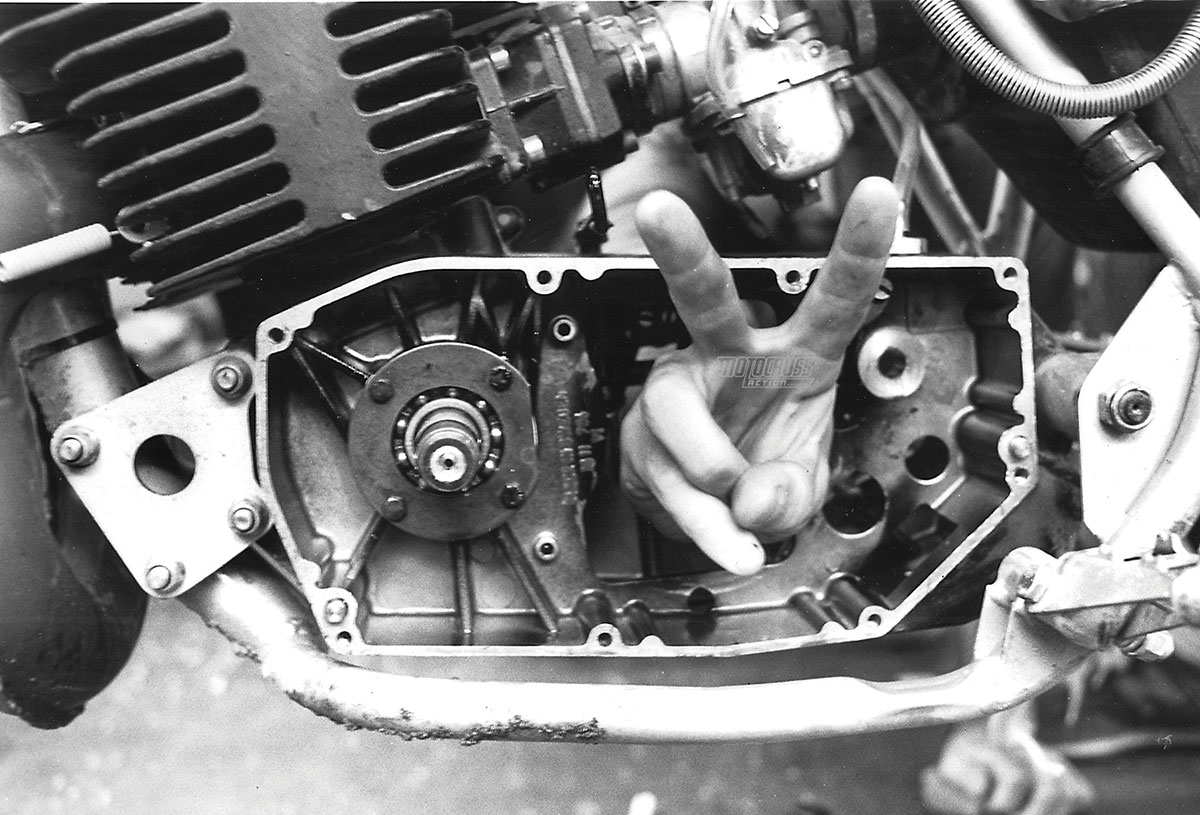

Husqvarna’s automatic transmission didn’t require splitting the cases to remove it.

Husqvarna’s automatic transmission didn’t require splitting the cases to remove it.

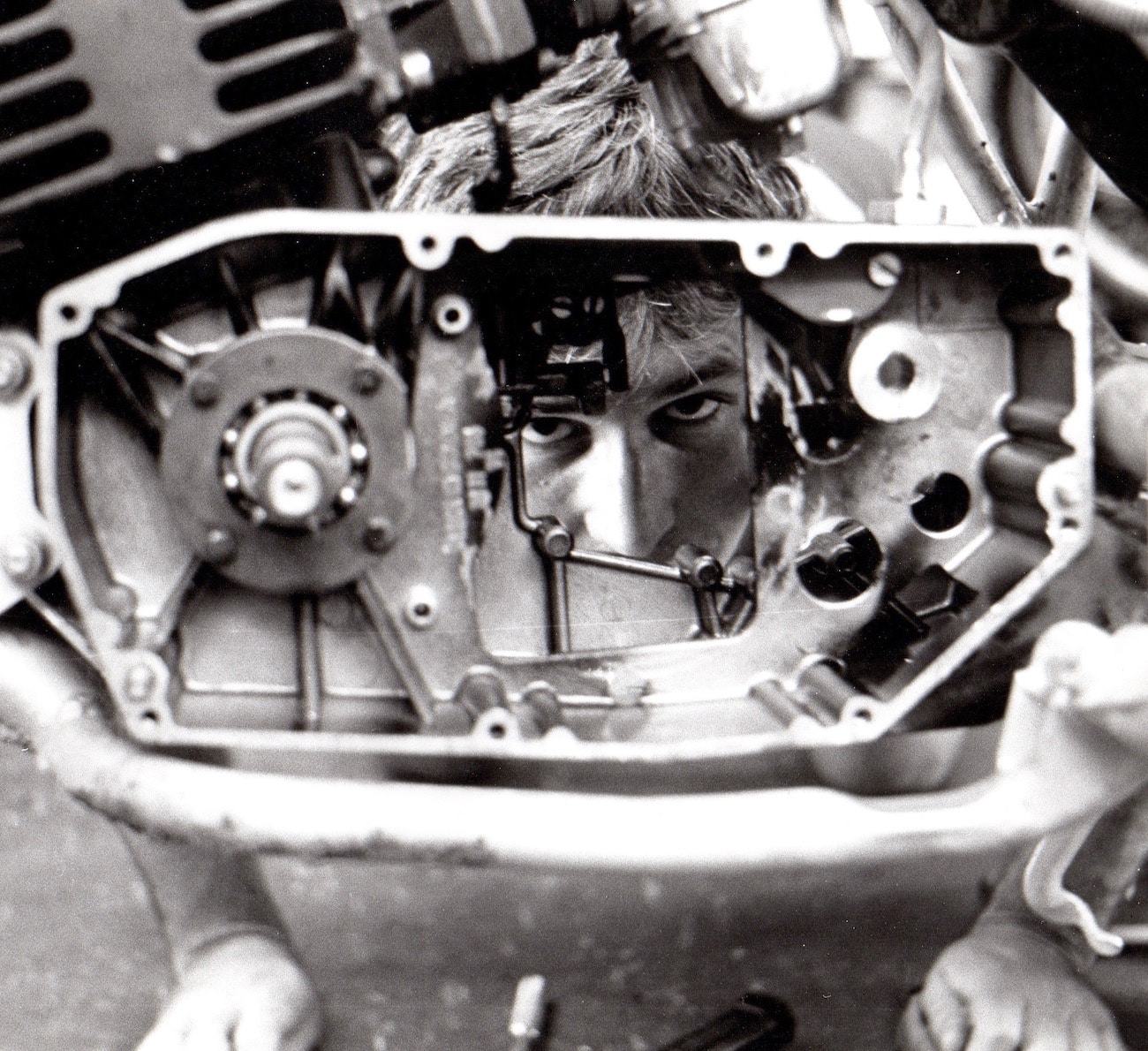

The perfect place to hide your valuables when working on your Husky Auto.

The perfect place to hide your valuables when working on your Husky Auto.

In stock trim, be it a 360, 390, 420, 430 or 500, the Husky Autos were not fast in terms of sheer horsepower. In truth, the complex sprag-gear transmission worked best with less load on it, which largely accounts for its phenomenal success in the National Enduro Championship in the hands of Terry Cunningham, Dick Burleson and Bob Popiel. Success in motocross was limited to Arlo Englund in the 1977 AMA 500 Nationals, Bo Edberg in the 1982 FIM 500 World Championship and a Pro Circuit-built bike with Honda forks, disc brakes and a 500cc engine that was raced by Steve Wiseman and Jody Weisel in SoCal in 1981–1982. Let’s forget about the very successful AMA enduro riders, because they didn’t have to deal with mass starts. Although you could get an Automatic over the gate first, there was a considerable amount of power lost to clutch-shoe slippage. All of the dog-bone cogs that looked like giant two-dimensional needle bearings were in contact with each other, but only the chosen gear was connected via its sprag gears. It was possible to get a good start, but most of the time it wasn’t in the cards.

As you approached the first turn, the next aspect of the Auto learning curve came to light. When you shut the throttle off, the Husqvarna Auto would freewheel. Husky Auto racers often said that when they chopped the throttle, it felt like the Husky accelerated towards the corner instead of slowing down. Luckily, you couldn’t stall it. The anti-stall characteristic enabled Auto riders to grab the Husqvarna drum brakes with all the force they could muster. Even though Husky brakes weren’t stellar, they could be applied with more force than on a manual-transmission bike.

ELECTROLUX, WHO HAD BOUGHT HUSQVARNA IN 1977, WAS READY TO UNLOAD THE MOTORCYCLE DIVISION. THE ITALIAN CAGIVA BRAND TOOK OWNERSHIP OF HUSQVARNA IN 1986 FOR LESS THAN $10 MILLION. CAGIVA DIDN’T WANT THE AUTOMATICS.

On the track, the Husqvarna Auto could cut laps that were incredibly fast. There were several reasons for this.

First, there was no stop and go riding on an Auto. The throttle was either on and the engine was rowing through the gears or the throttle was off and the bike was freewheeling into corners faster than sanity allowed.

Second, since the engine couldn’t be killed accidentally, the rider became acutely aware of what was happening. There were two modes to riding a Husky Auto—noise and silence. It didn’t take long for Husqvarna Auto riders to work on eliminating silence. The Auto is faster when the engine is making noise.

Third, comparable to a four-stroke, which suffers from too much decompression braking, the Auto’s total lack of engine braking allowed the rider—nay, forced the rider—to carry more speed into corners. It didn’t take very many corners for an Auto racer to understand that a little bit of noise all the time was one of the keys to success. Why? Because there was lag time from the time you got back on the gas until the sprag gears engaged. If you kept the engine running, even at a purr, the sprags would remain hooked up and the lag time would be shortened.

Fourth, every Husqvarna Auto motocross racer, and there were very few, claimed that with no clutch and no need to shift, it freed up brain power. It was asserted that things slowed down and lines became more visible when your brain’s frontal lobe wasn’t being used to coordinate two hands and both feet—just the throttle hand and the rear brake.

The small cadre of Husqvarna Automatic motocross racers had to find their own solutions to problem areas on the Auto. They couldn’t rely on previous experience riding conventional transmission bikes. Most of the solutions had to be discovered the hard way.

Fluid temperature. The transmission fluid (it wasn’t oil) got so hot that the engine cases could burn your foot through your boot. This wasn’t as prevalent for off-road or enduro riders, but the constant shifting and accelerating of motocross caused the multiple clutches to boil the fluid. In fact, if you tried to run the stock blue plastic oil-filler cap on an Auto, it would melt and hydraulic fluid would spew out of the transmission. It looked like your bike was on fire. The solution was to CNC machine an aluminum oil-filler cap.

Clutch springs. You could fine-tune the engine with stiffer or softer clutch springs. And, this was a common trick, but the biggest spring problem came from the 42-psi spring on the first gear’s centrifugal clutch. If the first gear springs broke during a moto, which wasn’t uncommon, the next time the rider revved his engine up after putting it in “drive,” the Auto would instantly accelerate because there was no spring pressure holding the shoes back. This would almost always throw the rider off the back as his bike jumped the forward-falling starting gates of the day and merrily went on up the track.

Fluid change. It was important to change the hydraulic fluid after every race. There was a lot of metal-to-metal contact inside the automatic transmission, and that mixture of brass bob weight debris and steel slag contaminated the fluid quickly. Plus, the fluid got so hot during a race day that it was useless to keep running the same stuff.

Forced downshifts. It wasn’t uncommon for a Husqvarna Automatic rider to enter a turn where he planned to come in at one speed and then hammer the throttle out of the turn in a lower gear. This didn’t always happen as planned, because sometimes the auto shifted up on the exit of the corner instead of down, which killed the engine’s punch. To solve this upshifting problem, riders would go into the turn, but this time with the throttle turned on and brakes holding the bike at the chosen speed. Dragging the brakes kept the transmission down in a lower gear long enough to guarantee a good strong drive out of the corner.

Educated left hand. Every Husky Automatic racer still reached for the clutch lever when push came to shove. The fact that it wasn’t there didn’t stop them from the reflexive action.

Every 360, 390, 420, 430 and 500 Automatic rider reached for the clutch lever that wasn’t there out of habit.

Every 360, 390, 420, 430 and 500 Automatic rider reached for the clutch lever that wasn’t there out of habit.

Getting a start. On the starting line, Husqvarna Auto riders would hold the brakes on and slowly rev the engine until they could feel the clutch shoes kissing the drum. Too much throttle and the bike would buck and quiver as it tried to move against the brakes. The goal was to shorten the lag time of the clutch shoes having to sling outward to make contact with the drum. If you had a delicate touch, you could get off the gate first.

Transmission. The complete gearbox could be removed without having to split the cases. MXA carried a spare transmission in a cardboard box to every race—just in case.

From its start as a Swedish Army motorcycle in 1973, the Husqvarna Automatic had some major hurdles to overcome. The first production Auto to hit American shores was the 1975 360 Auto. It shined on rough and tight off-road trails but had issues when ridden in motocross conditions. European off-road riders were leery of the automatic transmission, so Husqvarna pinned its sales hopes on American off-road riders whom they felt would be more open to new technology.

Terry Cunningham did his part to sell Husky Autos by winning five consecutive AMA National Enduro Championships (1982–1986) on the 420/430AE versions of the bike. Cunningham’s prowess proved that the bike had the potential to be a sales success. According to Gunnar Lindstrom’s Husqvarna Success book, “Sales of the automatics in the U.S. were strongest in the east, where the most difficult conditions were found, and almost nil in the west, where speeds were higher and terrain drier.” But the Automatic’s success in America did not translate into sales in Europe, save for Sweden, where Swedish off-road racers embraced the Auto wholeheartedly.

Husqvarna’s management felt that a motocross effort in the 500 GPs would energize sales on the Continent. To that end, Husqvarna entered a local Swedish rider named Bo Edberg on the 500 Auto works bike in the 1982 500 World Championships. After Edberg gave a decent performance in 1982, Husqvarna put the 500 engine (actually a 488cc) into the Automatic lineup as the 1983–’84 Husqvarna 500AE. The 488cc engine was a little too much for the Automatic. It revved too high, ran hot and vibrated more. It was obvious that the Auto worked best with modest power, and the 1986–1987 water-cooled, three-speed 430AEs were considered to be the best autos ever made.

In 1986, Husqvarna actually showed a profit, along with winning almost every off-road title in the USA. Things were looking up. However, the joy over the Auto was muted by the fact that appliance giant Electrolux, who had bought Husqvarna in 1977, was ready to unload the motorcycle division. On March 27, 1986, the Italian Cagiva brand took ownership of Husqvarna for less than $10 million. Since the Husqvarna racers had signed contracts for the 1986 season, they continued to be sponsored. As for the CR430, WR430 and 430AE, their production was moved to Italy, and the last Swedish-built Husqvarna rolled down the assembly line on December 3, 1987. Cagiva felt that it would benefit from an association with the Swedish brand, but Cagiva’s Italian management style chafed not only its U.S. employees but its U.S. dealers as well. Cagiva didn’t want the Automatics, and the inventory of 1987 430AE Automatics in the Ohio and California warehouses were dumped at rock-bottom prices. It was possible for a Husqvarna dealer to buy as many 430AEs as he wanted for under $500.

The rest is history. The arrival of Cagiva was the end of the road for the Husqvarna Automatics as well as any Swedish connection to the brand.

THE 1982 FACTORY 500 AUTOMATIC WORKS BIKE

Husky’s works 500 Automatic had a 488cc engine, sand-cast cases, lots of finning and, most intriguing, it had rear brake pedals on both sides of the bike.

Husky’s works 500 Automatic had a 488cc engine, sand-cast cases, lots of finning and, most intriguing, it had rear brake pedals on both sides of the bike.

Perhaps the most creative and innovative factory works bike to ever race the 500 GPs was Bo Edberg’s 1982 Husqvarna 500 Automatic. You have probably never heard of Bo Edberg—and that is understandable. Bo was a journeyman Grand Prix racer from Sweden who was picked by Husky to race its one-off 500 Automatic in the 1982 World Championships. He had never scored a Grand Prix point in his life up to this point, but he did on the 500 Auto. Bo qualified for every 500 Grand Prix and scored World Championship points in 1982 with more regularity than anyone expected. The spotlight shined on Bo, but was it Bo’s talent or was it his radical no-shift 500?

JODY WAS SMART ENOUGH TO BRING HUSQVARNA USA’S BOB POPIEL WITH HIM TO RIDE THE BIKE ALSO. POPIEL WORKED FOR HUSQVARNA AND HAD SPENT MORE TIME ON THE AUTO THAN ANYONE ON THE PLANET.

When Husqvarna wouldn’t let Bob Popiel ride Bo Edberg’s bike, Jody insisted, and Bob got to ride his dream bike.

When Husqvarna wouldn’t let Bob Popiel ride Bo Edberg’s bike, Jody insisted, and Bob got to ride his dream bike.

Husqvarna invited MXA’s Jody Weisel to fly to the Huskvarna MotorKlub to test Edberg’s one-off race bike at season’s end. Jody was smart enough to bring Husqvarna USA’s Bob Popiel with him to ride the bike also. Popiel worked for Husqvarna and had spent more time on the Auto than anyone on the planet, winning the Jack Pine Enduro twice, the Tecate 500 twice and ISDT gold medals twice. Once they were there, the Swedes only wanted Jody to ride the bike and told Popiel that he couldn’t ride it, but Jody convinced them that he needed someone else to ride Edberg’s Auto so that he could shoot action photos of it for the test. Husky relented. Bob was in seventh heaven.

Bo Edberg’s works Husky Automatic had sand-cast cases, ample finning on the cylinder and side cases and a brake pedal where the shift lever should have been.

Bo Edberg’s works Husky Automatic had sand-cast cases, ample finning on the cylinder and side cases and a brake pedal where the shift lever should have been.

Both Jody and Bob loved the 488cc engine. It was very brisk compared to the stock Auto engine and had a more deliberate feel to each shift, probably because the works three-speed transmission was custom-made for this bike. Most notably, Bo Edberg’s Husky had two brake pedals—one in the conventional position on the right side of the bike and one on the left side where the shift lever would normally go (in addition to the handlebar-mounted front brake lever). Edberg had developed a kind of heel/toe braking system that allowed him to freewheel the Auto into the corners, with his inside leg stuck out for balance while using the rear brake on the opposite side to modulate the velocity. Bo Edberg had mastered this delicate dance.

Given that Bob and Jody both raced Husqvarna’s Automatic, they loved Edberg’s works bike. It looked mean with its heavily finned engine cases, which must not have helped the cooling all that much because Edberg often complained that the 500 Auto lost power when it got hot at the end of the 40-minute GP motos. On the big Vattern track near the town of Huskvarna, Bob and Jody spun laps all day. They loved the power and the ease of use of this bike that neither of them would ever get to ride again. They didn’t want to get off.

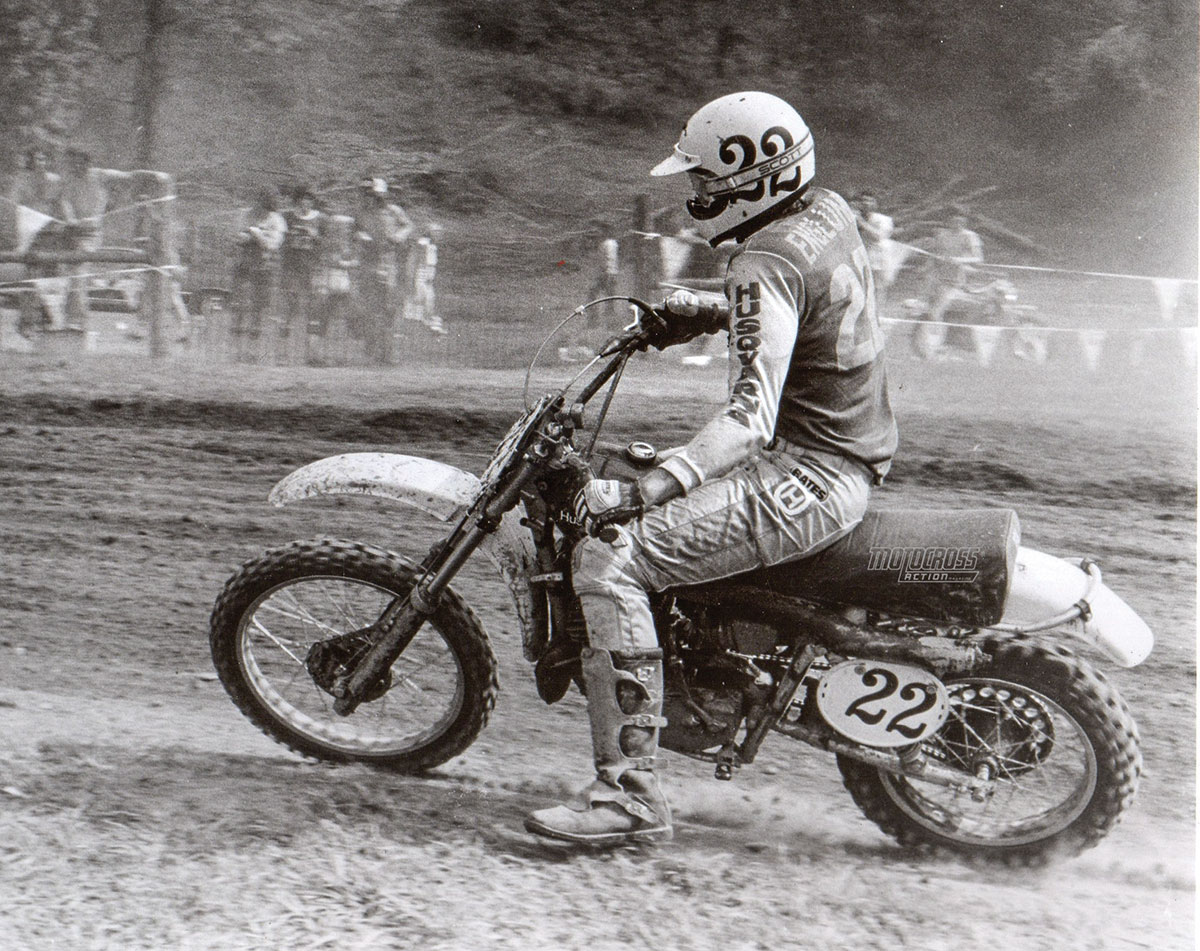

Bo Edberg, tucked in and flying, during the 1982 500cc World Motocross Championships on the works Husqvarna 500 Automatic.

Bo Edberg, tucked in and flying, during the 1982 500cc World Motocross Championships on the works Husqvarna 500 Automatic.

The question remains as to whether Bo Edberg’s bike was as good as they thought. Could this bike take a middle-of-the-pack racer and move him to the front? MXA felt that it made you faster because it demanded more of you. Look what it did for Bo Edberg in 1982.

1991 HONDA RC 250MA AUTOMATIC WORKS BIKE

Although tested by a handful of American Honda stars in Japan, the Honda RC250MA was raced in the 1991–’92 All-Japan Championship by Taka Miyauchi before being moved to the Honda Museum where it sits today.

Although tested by a handful of American Honda stars in Japan, the Honda RC250MA was raced in the 1991–’92 All-Japan Championship by Taka Miyauchi before being moved to the Honda Museum where it sits today.

In 1991 Honda raced a couple different versions of its automatic-transmission CR250. The works version, known as the RC250MA, was equipped with a hydrostatic (HST) transmission and was tested in the 1991 All-Japan Motocross Championship series by Taka Miyauchi.

On the prototype 1992 Honda RC250MA the kickstarter had to be moved forward because of the hydraulic wher eit woud normally have gone. You started the CR250MA by kicking the it forward.

On the prototype 1992 Honda RC250MA the kickstarter had to be moved forward because of the hydraulic wher eit woud normally have gone. You started the CR250MA by kicking the it forward.

It was also reportedly ridden by Jeff Stanton and Jean-Michel Bayle and is easily recognized by its forward-motion kickstarter.

THE HEART OF THE SYSTEM IS THE PUMP THAT BUILDS PRESSURE VIA THE CR250 ENGINE. HONDA’S OBJECTIVE WAS TO ACHIEVE AN INFINITELY VARIABLE TRANSMISSION THAT COULD RESPOND QUICKLY TO RIDER INPUTS.

The RC250MA’s automatic transmission is a blending of a Hydro Mechanical Transmission (HRT) and Hydrostatic Transmission (HST) in that it uses fluids to push a series of swash plates back and forth for seamless movement between the gears. The heart of the system is the pump that builds pressure via the CR250 engine. Honda’s objective was to achieve an infinitely variable transmission that could respond quickly to rider inputs—although Honda did test a 6-speed version that gave the sensation of shifting. All combined, Honda called its automatic a Human-Friendly Transmission (HFT). Following success in racing, albeit limited to two seasons in Japan, further research and development eventually resulted in a cross-over to Honda’s street bikes. As for the 1991 RC250MA, it now resides in the Honda Collection Museum at Twin Ring Motegi.

ARLO ENGLUND’S AMA NATIONAL EXPERIENCE

Arlo Englund is the only rider to ever race a Husqvarna Automatic in an AMA 500 National motocross race.

Arlo Englund is the only rider to ever race a Husqvarna Automatic in an AMA 500 National motocross race.

“1977 was a memorable year for me on the Husqvarna 390AF Auto,” says Arlo Englund, the only AMA Pro to race a Husqvarna Auto in the AMA Nationals. “Back then, Husqvarna’s U.S. headquarters was based in Nashville, Tennessee, while I was from Colorado. Luckily, Bill Thomas had a Husqvarna dealership in Denver, Colorado, and Bill was close friends with Husqvarna sales manager Bill Kniegge. I had raced a couple 250 Nationals in 1975 on a Bultaco, but when 1976 rolled around, I did three Supercrosses and five Nationals on a Kawasaki before switching to a Husky for the last five 125 Nationals.

“In the 1970s, the 125, 250 and 500 classes held their own separate Nationals (only the opener at Hangtown was a combined 125/250 National). Bill Kniegge was impressed by my five 1976 races on a Husky CR125. I had made the top 10 in every round and finished third overall at Delta, Ohio, behind Bob Hannah and Danny LaPorte, and fifth at the New Orleans final. For 1977, Bill Kniegge offered to give me a Husqvarna 390AF Auto for the 500 Nationals and a Husky CR125 for the 125 Nationals.

“The Husky Auto was truly a unique motorcycle that would automatically put you in the optimum gear for any technical section you could throw at it. When asked to race the AMA Nationals on it, I was a bit concerned about it automatically shifting when I launched off jumps, but I soon figured out that it shifted so smoothly that it was not an issue. On the racetrack, good lap times came easy. Getting good starts was the downside; I was always coming from the back of the pack, because when the gate dropped, your engine was basically at idle.

“After all the years of riding a dirt bike with a clutch and shifter, the transition to the Husky Auto was easy. The bike did a big part of the job for you. Some may talk about the freewheeling or lack of engine braking, but that was never an issue for me. Entering turns was good, because your tires had a much better chance at staying hooked up due to a lack of engine braking and smooth auto shifting. I did all of the mechanical work and maintenance on my bikes, but I had a lot of technical support from Husqvarna. My 1977 Husqvarna 390 Auto was basically in stock form. The only changes I made were playing around with the optional clutch springs to change the shifting characteristics and the engagement rpm.

“IT NEEDED A GOOD, FUNCTIONAL OIL COOLER AND A BETTER WAY TO LAUNCH OUT OF THE STARTING GATE. WITH TODAY’S TECHNOLOGY, I WONDER JUST HOW GOOD A FULLY AUTOMATIC DIRT BIKE COULD BE.”

“It is really too bad Husqvarna didn’t have more money to throw at this unique motorcycle. In motocross, the heat that the clutches created killed the reliability, especially on tracks with deep, loamy soil. It needed a good, functional oil cooler and a better way to launch out of the starting gate. With today’s technology, I wonder just how good a fully automatic dirt bike could be.”

Arlo would go on to have a successful AMA career, although he switched to Yamahas after the 1977 season. He would end up with 29 top-10 National finishes, with a fourth overall in the 1979 AMA 500 Nationals. He would go on to win the Pikes Peak hill-climb motorcycle division twice (1982 and 1991), but is most remembered for two things: (1) Winning the wheelie contest at Evel Knievel’s Snake River Canyon Motocross (beating Evel himself). And (2) for being the only Husqvarna Automatic racer in the AMA Nationals.

Comments are closed.