ONE MAN’S QUEST TO BUILD A 2003 WORKS KX125 TWO-STROKE

BY MARK CHILSON

My fascination with the Kawasaki KX125 started at the 1998 Chaparral Challenge. It was a pre-season warm-up race held at Glen Helen Raceway for the 1999 AMA Supercross series. It attracted lots of big-name riders, including Jeff Emig, Steve Lamson, Scott Sheak, Stephane Roncada, Tallon Vohland, Phil Lawrence, Nick Wey, Nathan Ramsey, Casey Lytle, Broc Sellards and Lance Smail. My wife and I came to the race to see our favorite riders—Ricky Carmichael, my favorite, and Jeremy McGrath, my wife’s favorite. But, by the end of the day, I came away impressed by a rider I had never heard of before. His name was Shae Bentley, and he won the combined 125/250 shootout, beating Jeremy McGrath (250), Jeff Emig (250), Casey Lytle (125), Stephane Roncada (250), Tallon Vohland (125), Chris Gosselaar (125) and his two Pro Cir-cuit/Splitfire teammates, Ramsey and Wey. I was in awe of Shae’s full-race 1999 Kawasaki KX125. A year later, Shae Bentley would win the AMA 125 West Supercross Championship on his Todd Dunn-tuned KX125. I never forgot that day on the Glen Helen Supercross track, and later I was fortunate enough to become friends with mechanic Todd Dunn.

IN 2010, ON MY WAY HOME FROM WORK, I SPOTTED A USED KAWASAKI KX125 AT A BIKE SHOP NEAR MY HOUSE.

A LIGHT BULB WENT OFF IN MY HEAD, AND WITHOUT HESITATION I PULLED IN. IT WAS A 2003 KX125.

In 2010, on my way home from work, I spotted a used Kawasaki KX125 at a bike shop near my house. A light bulb went off in my head, and without hesitation I pulled in. It was a 2003 KX125. As I looked it over, I noticed that there was not a stripped bolt in sight. The vent spews were still on the knobs, and it appeared to be a bike that someone had ridden once and then stored in the garage for the next seven years, waiting for me to drive by. I decided to buy it on the spot.

I suppose I was triggered by the sudden passing of Todd Dunn from a heart attack a few months earlier, but I decided to build my own Kawasaki KX125. It was not a 1999 or 2000 KX125, as Shae’s bikes had been, but it was the perfect bike to make a project out of. It would be my loose interpretation of a replica of the bike that Shae and Ricky Carmichael raced to glory. My racing buddies know that I cannot leave anything alone. I picked that up from my father, a former Indy 500 mechanic, and my goal was to do nearly everything myself and fabricate my own parts for my 2003 Kawasaki KX125. Little did I know when I started this project that I would still be working on it 10 years later, but I had a plan, and I stuck to it.

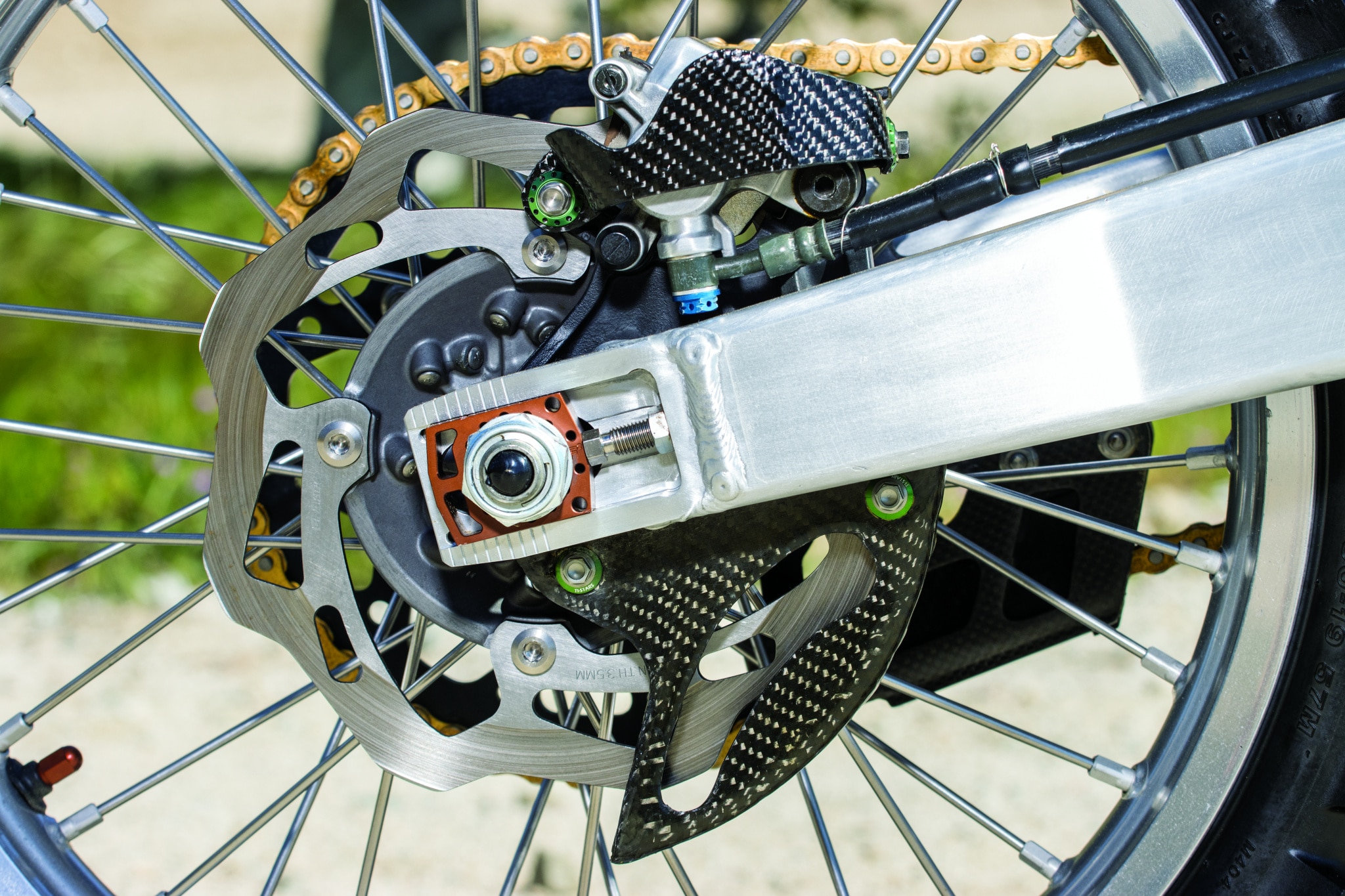

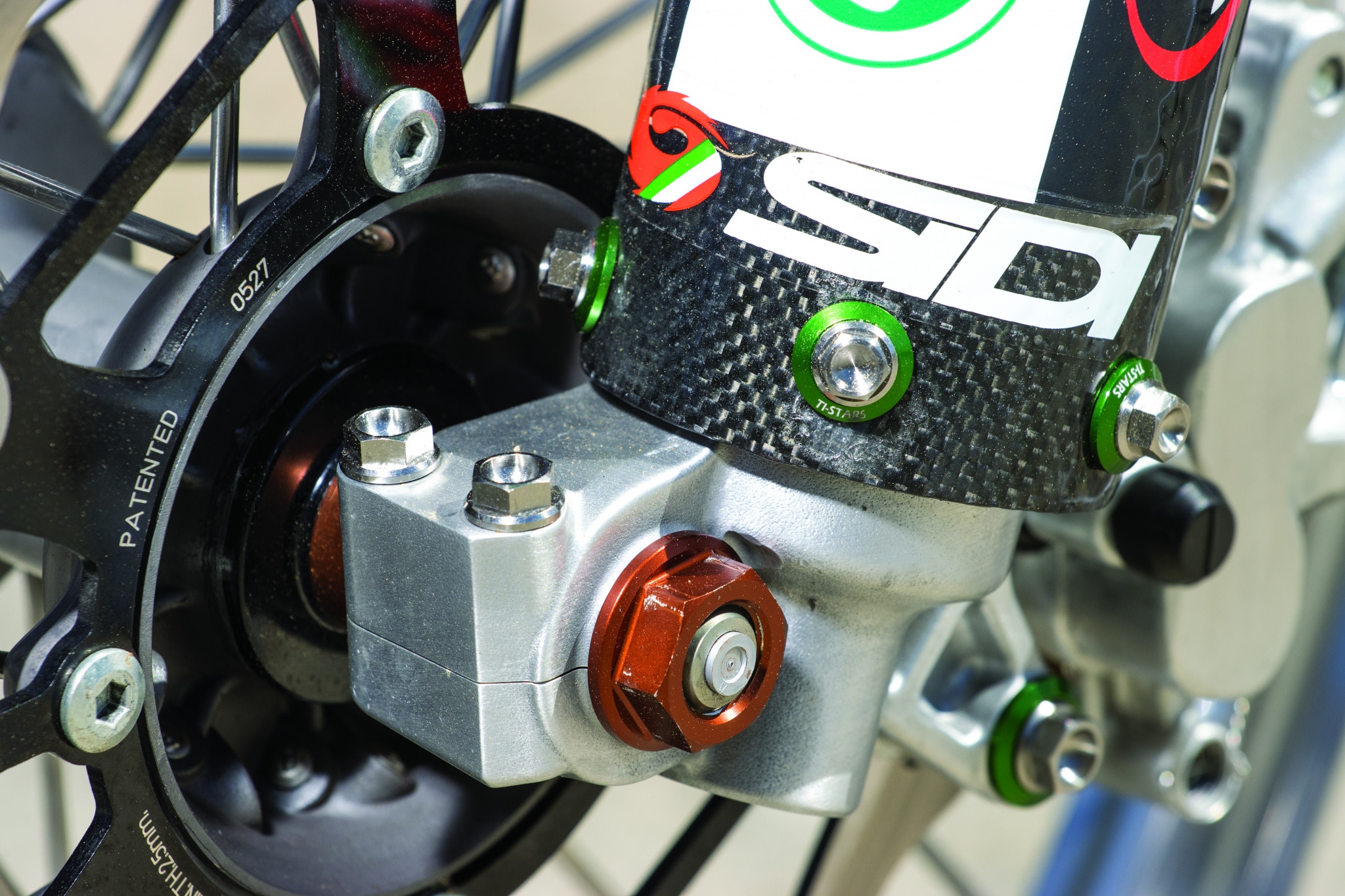

First, my KX125 needed to lose weight. I knew that a YZ125 weighed 199 pounds, and my KX125 was a fat 208 pounds in stock trim. I started by turning down the stock hubs. Then, I had them hard-anodized clear and laced up with polished stainless-steel Buchanan spokes. I cut and shaved every part I could to reduce as much unsprung weight as possible. That meant milling the brake calipers and master cylinders and building new aluminum brackets to replace the stock steel parts. I machined an aluminum rear brake clevis and added a titanium pin. I weighed every part on the bike in search of grams and ounces. I replaced the front and rear axle nuts with self-locking Honda nuts. I replaced nearly all the hardware with titanium (minus the linkage bolts and axles). All in all, I removed 9 pounds, making my 2003 KX125 weigh 199 pounds.

Second, I wanted superb suspension. Knowing the KX had old Kayaba bumper forks, I found a set of Kayaba SSS forks from a 2007 YZ250F. They bolted right on after being re-valved by Graeme Brough Suspension. The shock was the stock Kayaba unit, which was re-valved by Graeme and had a KHI bladder assembly and bladder cap added. I ran a Yamaha titanium shock spring that had been sitting on Graeme’s shelf for years.

MY ULTIMATE PLAN, AS WITH MY 2002 HONDA CR250 PROJECT BIKE BACK IN 2019, WAS TO RIDE IT ONCE TO BREAK IT IN AND THEN SHOW IT TO THE MXA WRECKING CREW IN HOPES THAT THEY WOULD AGREE TO RIDE IT FOR ME.

Third, I started with an oversized Galfer front rotor and a 2019 KX250F rotor for the rear. Because I was still using the 2003 Kawasaki front wheel, I had to fabricate new wheel spacers, along with a YZ front axle and brake caliper. I replaced the stock front master cylinder with the Brembo caliper that Grant Langston used on his National Championship YZ450F. I mounted the forks via a set of Universal triple clamps, and I came across a set of James Stewart-bend 7/8-inch bars.

Fourth, having a modicum of experience in making carbon fiber parts and mold making, I made my own lower fork guards, ignition cover, ignition wire guard, rear brake caliper guard, disc guard and a few other parts. I grafted a set of Pro Taper footpegs with hand-turned titanium clevis pins.

Fifth, the frame was stripped and powdercoated Bengal Silver. The swingarm was polished by hand to get that clean factory look. When putting the chassis back together, I machined a 1.25mm-longer shock linkage and anodized it green. I turned to Jeff at SDG seats to get a custom seat cover made to fit over my cut-down seat foam. 180 Decals made up a set of 2003 Factory Chevy Trucks graphics (personalized for me).

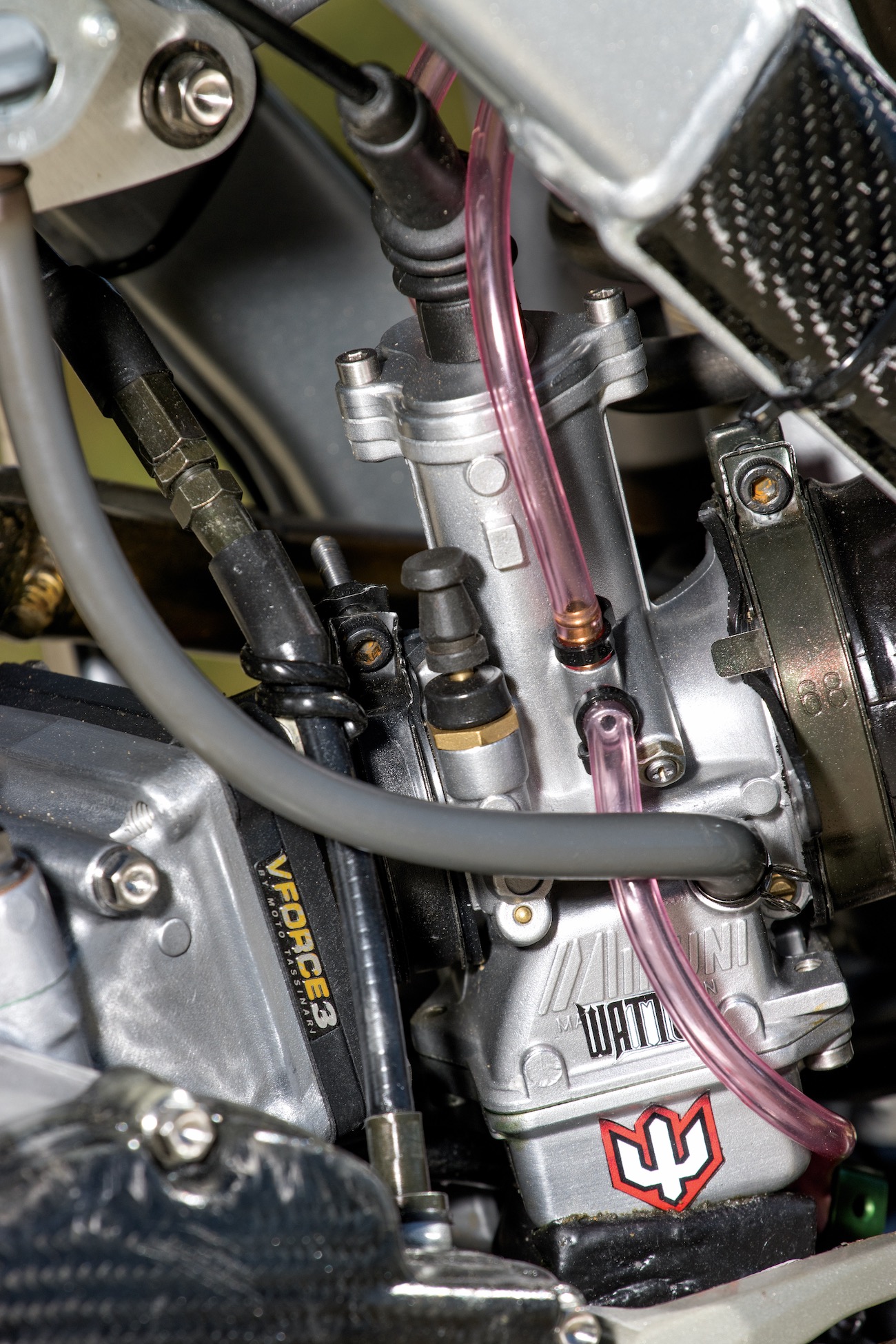

Sixth, knowing that there are not too many 2003 KX125 parts laying around anymore, I went with a mild engine combination. The cylinder ports were cleaned up and smoothed out, and the exhaust side was polished along with the cylinder head. I added a thinner Athena base gasket. You can’t build a hot-rod KX125 without a Pro Circuit pipe and 304 silencer. I did modify the silencer by replacing the aluminum canister with a polished titanium one, and, of course, I made a new bracket. The stock carb and Moto Tassinari reed assembly were sent off to Watts Performance, where Chad Watts modified the carb internals and intake. To emphasize throttle response, Chad had me install a Pro Circuit carb canister kit per his specs. Chad was Ricky Carmichael’s mechanic at Pro Circuit Kawasaki, where he specialized in spotless levels of detail and finish, setting his bikes apart from the rest. Air is fed through a custom-made intake tract using a Loudmouth-style filter. Jetting on my KX125 was a 37.5 pilot with the stock needle on the third clip with a 410 main and a 50/50 mix of VP 110 race gas and 91-octane pump fuel. Life is sparked through a JD ignition module. The radiators were lowered 10mm with handmade brackets and titanium hardware.

My ultimate plan, as with my 2002 Honda CR250 project bike back in 2019, was to ride it once to break it in and then show it to the MXA wrecking crew in hopes that they would agree to ride it for me. They have spent more time on hopped-up vintage bikes than anyone I know, and they are experts at telling the truth. When they tested my 2002 CR250 in the March 2019 issue, they gave me valuable feedback on the triple-clamp offset (that I had changed) and my TwinWall handlebars (which fed too much stiffness into the billet triple clamps), and they gave me some gearing suggestions (to broaden the powerband). It took me some time to convince them to test my 2003 KX125, but I couldn’t wait to hear what they thought about it.

WHAT THE MXA WRECKING CREW THOUGHT OF MARK CHILSON’S 2003 KX125

“This is Daryl Ecklund. I need to cut Mark short right here, as he could write a 200-page memoir about his 10-year love affair with his KX125. I just hope I don’t cause tension in the relationship between Mark and his bike after we doubled the time on his KX125’s hour meter, stretching its lungs up Mount Saint Helen. No hard feelings, Mark, but we are going to give you the hard truth about your build. Buckle up.

“Let’s be real. Is a 2003 KX125 going to be competitive in the new age of 125cc tiddlers? I would consider a Mitch Payton 2003 KX125 engine to be competitive in this environment, but Mitch is the best in the business and has access to unobtainium. Mark wasn’t delusional; he knew he wasn’t going to beat out the new blood. So, why dump so much time and money into a bike that wouldn’t have a competitive advantage on the starting line in 2021? The same reason I built my own 2003 KX125 from a box full of parts a few years ago. It all starts with a story, a memory of something you want to bring back to life. This is the bike Mark built from a narrative played back years ago. Now it was time to put his dream build to the test.

“OVERALL, THIS BIKE BROUGHT BACK THAT WARM, FUZZY

FEELING OF TWO-STROKE FUN. EVERY TESTER, INCLUDING ME, LOVED RIDING THIS BIKE.”

“On the track, the first thing I noticed about Mark’s KX125 was its comfort. It took no time at all to adapt to the green machine. You have to understand how rare this is. Only a handful of bikes I have ridden have had this instantly homey feel. It is a feeling that inspires confidence. The ability to hit an off-camber, square-edge bump or a nasty kicker off the take-off of a big double and not worry about how things are going to turn out on the other side is a rare sensation. This feeling comes from not just the balance between the old Kayaba shock and SSS forks, but the supreme valving job that Graeme Brough achieved. The suspension felt like a plush set of $10,000 A-Kit components. The fork and shock offered a supple few inches of travel at the beginning of the stroke. As the action of the suspension moved down towards the bottom, it offered a soft but firm feel that held up well. We were most impressed with its plushness on really hard hits. We expected this plush suspension to eventually bottom out, but it never did.

The suspension made the overall handling of the bike better than what an actual 2003 KX125 feels like in stock trim. Also contributing to its good handling were its lowered radiators, longer shock linkage (to bring down the rear of the bike) and cut-down seat, which gave the KX125 a more modern feel. Around the same time, I had been testing the 2021 CRF450 and Beta 300RX, which both have thin seats with little foam padding, making me appreciate the big foam seat on the KX125. It was like having extra suspension! I don’t think modern seat padding should go back to the old-school couch-style feel, but frankly, I am tired of getting bruises on my rear end from hitting the frame rails on some of the new bikes.

“Overall, the bike felt smaller than a KTM 125SX. The wheelbase felt shorter, and the chassis felt lower to the ground. This allowed me to ride the bike very aggressively. I could cut and weave to any line on the track instantly, something that is impossible with the sheer power and centrifugal force of a 450 four-stroke engine. While the tiddler was underpowered compared to the big four-strokes at Glen Helen, I was able to ride totally different lines from the other riders. I could go tighter in turns, which was also due to the superb brakes, and make cuts, down or up, without any hesitation. This allowed me to gain time on the bigger-displacement bikes.

“With Mark shaving nearly 10 pounds off his bike from stock (with a lot of it being unsprung weight), the bike felt remarkably light in the air and through corners. This was probably another reason the bike had such impeccable maneuverability around the track.

“I admit, I was surprised by how this old dog handled on the no-nonsense Glen Helen terrain, but I questioned whether it could tackle the big hills with its 18-year-old engine? The 2003 KX125 engine in stock trim produced right around the same peak horsepower as a 2021 YZ125. No surprise; the 2021 YZ125 engine is basically the same as it was 16 years ago. Saying that, the modified KX125 engine didn’t light the world on fire. This wasn’t an engine you would line up with in the Pro class at the World Two-Stroke Championships (more of that on page 64). Mark built his engine to last. Kawasaki stopped making two-stroke parts long ago, and there isn’t much available on the used market, so Mark felt it was best to play it safe rather than take a chance on ruining a cylinder that would be hard to replace.

“Riding older two-strokes is a lost art form. You can’t just grab a handful of throttle and expect the power to come alive like a modern-day thumper’s. These older two-strokes, like Mark’s KX125, have to be ridden with a precise right wrist and quick left hand. To get the most out of the bike, I had to thread the needle on shift points to keep enough momentum rolling through corners so I wouldn’t have to fry the clutch to get the power into the narrow powerband. This KX125 had broader power than what I remember a 2003 KX125 feeling like. Once I got the rpm in its sweet spot, the power kept climbing. It had a slight dip in power on the top, which I originally thought was my shift point signal, but when I shifted on the dip, this old dog—was a dog. It turned out that right after the slight dip, the afterburners kicked in. This 2003 KX125 howled until the cows came home. I loved that the power didn’t fall off, but I would rather have sacrificed some top to get more power off the bottom. The high-rpm power would work best for a true two-stroke specialist, but for the average joe, I would have gone with a bigger rear sprocket and done some fine-tuning. Honestly, it was a weak spot for me. When I made mistakes, it took a lot of clutch and shifting to get the bike going again.

“Overall, this bike brought back that warm, fuzzy feeling of two-stroke fun. Every tester, including me, loved riding this bike. You could feel the passion that was behind the build on the track. It is rare to have this much fun on a bike in the age of modern four-strokes. In a sense, I feel like the sport has lost its way. It is more about sheer power and less about the fun factor. We can blame the AMA for that. Mark is an inspiration to anyone who has a dream build in mind. He is one of the few who is more worried about having fun than winning. The older I get, the more I have to agree with him.”

Comments are closed.