TREVOR’S 24 HOURS OF PAIN: TREVOR NELSON’S BIG ADVENTURE

Q: WHY WOULD ANYONE SIGN UP TO DO A 24-HOUR ENDURANCE RACE BY THEMSELVES?

Josh Mosiman: I’d like to take credit for coming up with this idea, but I didn’t come up with it originally. I raced the 24-Hour in 2020 on a Pro team supported by Pro Circuit and JCR Honda. Mitch Payton bought us a Honda CRF450X. Mike “Schnikey” Tomlin built it for us, and Johnny Campbell provided us with his ace mechanic, Gage Day, and all the experience and knowledge we needed to set up the CRF450X for success. I teamed up with my friends, Carlen Gardner (now Beta USA’s Supercross Team Manager), Zac Commans (now working at Kawasaki in the test department), and Preston Campbell (Johnny’s son who races Pro off-road). We went on to win the event and had a blast doing it.

When I heard that Zac Commans was lining up for the 24-Hour again, this time in the Ironman class on a Kawasaki KLR650 dual-sport bike, I immediately thought, “He can’t have all the fun!” I almost decided to do it with him, but then I realized that we have an off-road rider in our crew who would be perfect for the job, Trevor Nelson. Trevor is usually behind the camera, and I’m in front of it. We decided that he should race the Ironman class and I should shoot the photos!

Trevor Nelson: I’ve been at MXA since 2019, and I enjoy off-road racing, especially desert races like the District 37 Hare and Hound events; however, with my job nowadays, I don’t have much time for riding myself. As the digital editor for Motocross Action, I’m in charge of taking the majority of our photos and videos, plus I design MXA’s magazine covers and all our logos and T-shirts.

When Josh asked me, it didn’t take much convincing. I had been at MXA for several years, and I finally had the chance to customize my own bike with more than just new grips and a seat cover. So, I said yes after about 20 minutes of thinking it through. I had captured Josh’s previous victory for the magazine and thought, “What could possibly go wrong?”

Q: HOW DO YOU PREPARE FOR A 24-HOUR RACE?

Josh: Mosiman Truthfully, when I began the process of convincing Trevor to race the Ironman class, knowing it was the toughest race of the year, I didn’t think he would agree to it. I figured that he would ask Josh Fout and me to do it with him as a team. Of course, I would’ve been happy to do it that way; however, about a week and a half before the race, I realized he wasn’t backing out of doing the race solo! Every time I opened my front door, I found more boxes with Trevor’s 24-Hour parts laid across my porch. This was an added benefit of having Trevor race the 24-Hour—he was getting a purpose-built CRF250RX race bike set up perfectly for him.

Trevor Nelson: This is the part of the story where I explain the process of preparing my 2024 Honda CRF250RX for the 24-Hour race. Well, in truth, there was little to no preparation other than bolting everything on just two days before the event. When you’re the digital editor at MXA, you don’t have the luxury of free time, and, honestly, not overthinking the race beforehand was a huge factor in how I showed up mentally. I had zero expectations, zero stress and zero clue what it would be like to ride for 24 hours—but we’ll get to that in a bit. The only thing I was worried about was if my camera equipment would come back in one piece after Josh Mosiman and Josh Fout played around with it for 24 hours.

Q: HOW DID WE PREP THE HONDA CRF250RX FOR 24 HOURS OF PAIN?

Josh: Thankfully, the CRF250RX is already a durable and capable machine, so I wasn’t too worried about the bike lasting for 24 hours; however, I knew that if Trevor were going to see the checkered flag, he would need a comfortable bike that wouldn’t beat him up. Trevor has lots of experience in multi-hour desert races and enduros from his time before MXA, but he’s never built a bike to last for 24 hours straight. I told him I would be his mechanic and photographer, and I would make sure all the right parts were ordered and installed. (Of course, I called Josh Fout and got him to wrench as well, knowing full well that he’s a better mechanic than I am and we were going to need all the help we could get). The first company I called was Nuetech to order some Nitromousse bibs for the wheels. You never want to change a flat tire when racing off-road, and Nitromousse is the go-to mousse brand for MXA. Also, we were able to run one wheel for the entire 24 hours (crazy right!). The Superlite sprocket with the stock Honda O-ring chain held up the entire time. TM Designworks has a unique “return memory formula” material that is perfect for chain guides and sliders. It’s strong, protected the chain whenever Trevor smashed into rocks, and lasts forever.

As a moto guy, aluminum radiator braces weren’t the first thing that came to my mind when adding up the parts needed, but I’m sure glad I didn’t forget them! I witnessed Trevor tipping his CRF250RX over many times in the middle of the night, and his radiators would’ve been toast without the Works Connection braces. I truly think they saved his race.

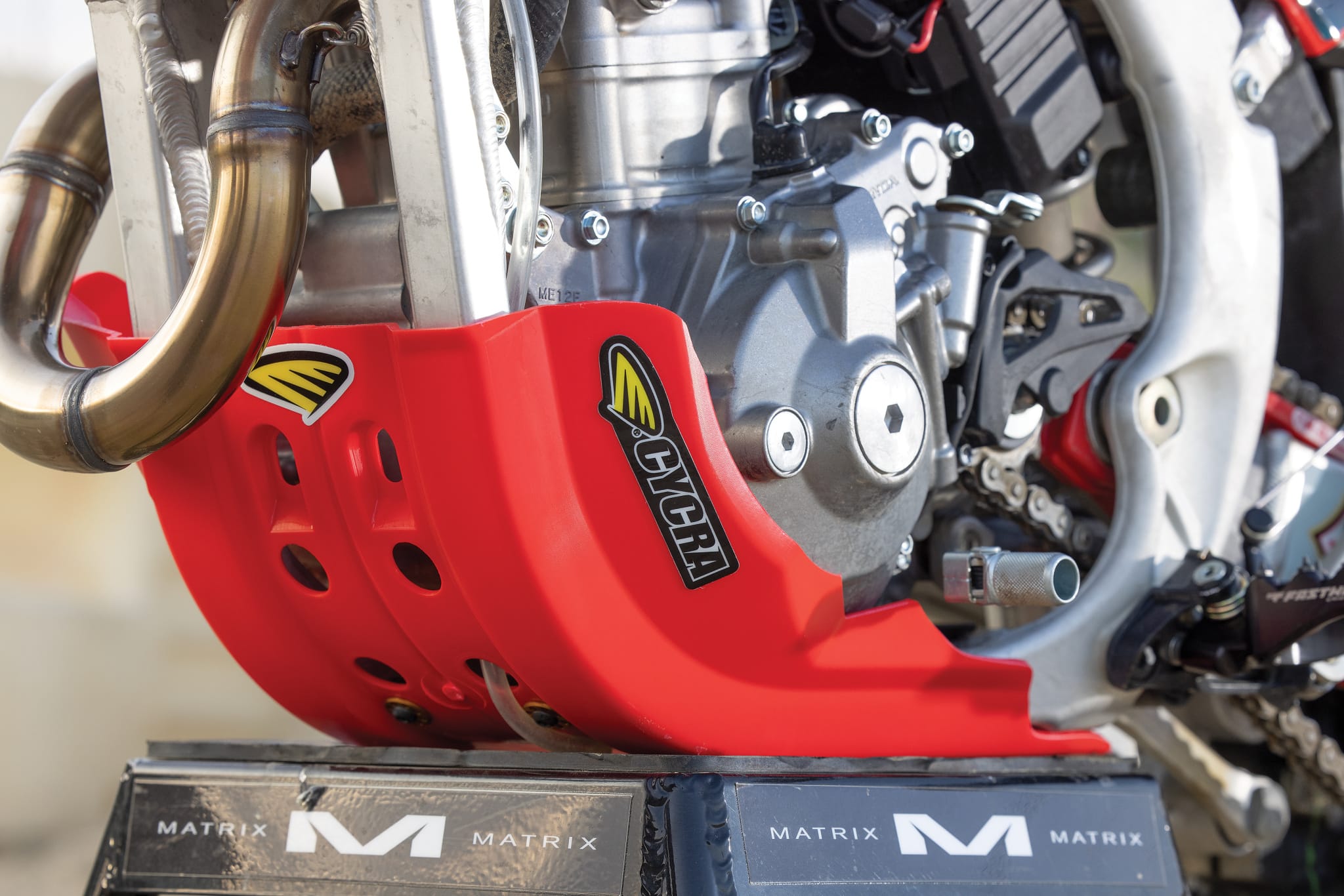

The CRF250RX comes with a skid plate, but it doesn’t offer the most coverage. I ordered Trevor a Cycra skid plate that was stronger and bigger, plus we got him Cycra hand guards and plastics to protect his hands and also keep the stock plastics nice for when we have to return the bike to Honda. Most of our readers have heard of ETS fuel being used in high-horsepower race bike builds and the factory KTM, Husqvarna, and GasGas bikes, but ETS also makes great price-point blends that are cleaner burning than pump gas and more affordable than race gas. We used ETS Extrablaze 100 fuel.

As for tires, we put the Dunlop MX53 tire on the rear because it has a harder compound and is tailored more for harder dirt. We installed the AT81 tire on the front. We thought Trevor would need new tires mid-race, so we had a backup set of wheels ready, but he made the original rubber last! Also, after RevX Max Power helped our FC450 pass the no-radiator test a few months back, I knew it would be a good product to run in Trevor’s race bike. The 2-ounce additive helps better lubricate all the moving parts inside the engine and keeps the bike running cooler. Of course, we had multiple pre-oiled Twin Air filters ready to go, because the airbox cover on the CRF models is prone to letting a lot of dirt in. The intake “mouth” on the side number plate is wide, so to limit some of the dirt and dust from coming in, I used Twin Air’s thin air filter skin to cover the big gap in the airbox cover. It was a protective piece that also made the bike look like a factory off-road bike.

Trevor: Thankfully, we had a lot of cool companies that were willing to support my adventure. I appreciated all the different companies, but Desert Unlimited was surely the golden ticket to the race itself. With all the things that we put on the bike, I wouldn’t have been able to finish the 12 hours of night riding without, you guessed it, lights. Desert Unlimited hooked us up with a CRF450L number plate custom mounted with a Baja Designs light pod in the center as well as two smaller Baja Designs pod lights that we mounted to my helmet. With my first project bike underway, I knew I wanted it to look unlike any project bike that we’ve done in the past or any other bike that I have seen. Decal Works designed a custom set of graphics to make the 24-Hour bike look like a beast of its own. Another component of the bike that saved me in the long run was ASV’s F4 series levers, which “came in clutch” when I inevitably sent the bike sailing in the middle of the night. The Yoshimura RS-12 exhaust system was the cherry on top, as it completed the build. It also freed up the bike’s engine braking, allowing me to carry more momentum through some of the nasty technical sections.

When you ride as little as I do, arm pump can become a nightmare; but, thanks to the Fasst Co. Flexx bars, a lot of the little bumps and chatter were smoothed out. ODI’s Rouge Lock-On grips provided an extra amount of cushion for my hands as well. Our good friend, test rider and contributor Brian Medeiros, has his own suspension company, Ekolu Suspension, and he made the CRF250RX suspension even softer. We felt it was yet another key feature that made the long moto just a little bit less grueling. And finally, for the bike’s upgrades, Guts hooked me up with a taller seat with softer foam. The idea was that the tall seat would allow more cushion for the nether region and decrease the stand-to-sit distance. We also equipped the seat with ribs and a seat bump strategically placed farther back than normal so that I wouldn’t notice it for 24 hours, but it would be a failsafe if I were falling backward on the bike. And finally, Trident Coffee kept the pit crew running through the night—well, at least it kept Josh Fout running and awake for the entire 24 hours. Josh Mosiman was caught sleeping in the back of the van when I pulled in wanting gas. I also used Fastway’s Evolution Air footpegs which are extra sharp to help me keep my feet in position.

Q: WHAT WAS THE FIRST LAP OF THE 24-HOUR RACE LIKE?

Josh: The 24 Hours of Glen Helen Endurance Race starts at 10 a.m. on Saturday and ends at 10 a.m. on Sunday. I was giddy with joy for about two weeks leading up to the race, excited to watch our cameraman suffer and reach a new level of toughness through doing this race! Trevor excels at anything he sets his mind to. He’s grown substantially since joining MXA with his photo and video skills, and he’s not afraid to work hard, even if it means sacrificing sleep. On the day of the race, Trevor was nice enough to hand me his camera (which is more expensive than mine), because he knew that the video quality and photo quality would be better if I was using his gear. He gave me some quick tips for his high-tech equipment. I prepped a pair of goggles for him. Josh Fout prepped his bike, and he was on his way to the starting line! In the last 30–40 minutes before the race, you could tell it was all starting to weigh on Trevor. He wasn’t talking much, and his normal happy-go-lucky attitude was switched out for a new “survival mode” mindset—and that mindset stuck for the entire 24-hour period.

Trevor: It had been some years since I’d lined up to race. Josh will tell you my mindset had changed, but I didn’t want to think about it too much. Honestly, it was a weirder feeling being on the other side of the lens than riding for 24 hours. When we lined up, I did not expect to do well, just to finish the race. I thought of it more like a marathon run or a long trail ride. My good friend Zac Commans was racing as well, and I was more excited to see him send the massive Kawasaki KLR650 than anything. I couldn’t believe how big it was, and it was just so funny. As the rows took off one by one, the Ironman class was last. Not much was running through my brain other than “Do not crash on your first lap; just check out the track.” So, as the green flag came out, we set sail. I didn’t really care to get a good start, but sure enough, that giant KLR650 pulled ahead of me, and I just busted up laughing in my helmet. As we went around the moto track and made our way up into the ridges of Glen Helen, I tailed Zac as he carelessly jumped past down arrows and blew through turns. It was quite hilarious following him around as I attempted to memorize the track.

By the time the first lap had finished, I had already pulled the rookie mistake of ripping all of my tear-offs off in one yank, thinking it surely had to be Josh’s fault. I signaled them to grab me a new set of goggles, and the race continued. What little strategy I had was to ride at a pace I thought I could ride at during the nighttime. This would mean to ride purposely slower than I am used to and to go even slower than that. Setting a lap time of around 27 minutes, the laps began to rack up as I would pull in after three to four laps and refuel with 10-minute breaks in between.

Q: LET’S SPLIT THE RACE UP INTO PERSPECTIVES. HOW WAS IT, FELLAS?

Josh: From the get-go, I was on the track with the camera, taking photos and videos of Trevor and Zac. Every lap they came around, I was laughing at Zac as he tried to maneuver the massive KLR650 around the track, and I was laughing at Trevor, knowing that he was in for a world of pain in the coming hours. I could tell that Trevor was serious about making it to the finish line because of how cautious he was early in the race. He wasn’t making any mistakes and he was riding below his abilities, just to make sure he saved his hands, arms, legs, and mind for the long haul. I’ll let Trevor tell the rest of the story from here.

12:00 NOON (HOUR 2)

Trevor: By the time a couple hours had passed, I was feeling good, really good. I was simply trail riding the course and taking each segment of the track one at a time, noting which parts of the track I would have to focus on as they got rougher each lap.

2:00 P.M. (HOUR 4)

Trevor: By the time four hours were over, I still hadn’t thought about it too much. I was just going through the motions of riding the CRF250RX cautiously and safely. There were several parts of the track that were starting to get rougher than others. Two sets of rock gardens, a silty uphill, a long downhill that follows Glen Helen’s valley, and the long and vertical uphill that connects the ridges to the moto track were on my “don’t mess around list.” Every time I would reach these obstacles, I had to lock it in. Any one of them could very easily ruin your entire day. These obstacles alone made it impossible to simply ride the track as slow as walking speed, as their existence became a thorn in my side in the later hours.

4:00 P.M. (HOUR 6)

Trevor: By the time the sun had begun to set, my body wasn’t feeling too great, and by “body,” I mean my stomach. This was the longest I had ever ridden, and up to this point, I was still doing three to four laps with a 10-minute break in between. My innards being jostled for this long was starting to take a toll on me. The Joshes began giving me snacks, and each bite would ignite an incredibly viscous gastrocolic reflex, setting my insides ablaze. Even something as silly as eating a gummy bear would be unnerving to eat. We strapped the helmet lights on as the sun began to make the traffic difficult to navigate. The headlights were too bright to ride the hills at speed, and without them, it was too dark to make normal visual navigation feasible. In the transition from daytime to nighttime, I rode the slowest that I would ride over the 24 hours.

6:00 P.M. (HOUR 8)

Trevor: Eight hours had passed, and my body was slowly becoming less stoked after each passing lap. At the beginning of the race, I had told my team not to bring up how good or bad I was doing, position-wise. My goal was just finishing. As the hours ticked away, I wouldn’t think of much other than just riding. In some spots, it was a tad boring, but by that time the track had started to get rough and the weather had taken a turn for the worse.

8:00 P.M. (HOUR 10)

Trevor: Nearing the halfway point, it was already pitch black out. I had never ridden in the dark except two days before when I spun two laps at Glen Helen at sunset before they kicked me off the track. This was foreign territory to me, something completely new. But, what I wasn’t expecting was how fun it could get (as long as someone wasn’t in front of me). By nighttime, boredom had set in, and I was itching for a change of scenery. What many who are reading this article don’t know is how dark Glen Helen can get at night. You will feel lonely in the pitch-black abyss of the Glen Helen mountains until a shimmer of someone’s passing headlights lights up a tree as they close the gap on you. Many of the teams had also slowed their pace, and other racers coming into my zone would become few and far between. Many say that getting to the nighttime alone is an accomplishment in itself, but I was keen on finishing the race in its entirety.

10:00 P.M. (HOUR 12)

Trevor: At the halfway point, every part of my body was aching. Parts I didn’t think were going to be hurting were hurting. Thankfully, the halfway point also marked our first big milestone. I pulled the bike in and the crew changed the oil. The team next to us was our sister publication’s team, Dirt Bike Magazine. Led by one of Hi-Torque’s Seth Barnez, the team was composed of current and former U.S. Marines. While the two Joshes were my main pit guys, the rough and tough lads next to us provided plenty of moral support, forcing me to eat spoonfuls of mustard and chug electrolyte water. My body was not pumped on any food, even the In-N-Out hamburger and fries that showed up in the middle of the night thanks to Dennis Stapleton.

12:00 MIDNIGHT (HOUR 14)

Trevor: This is when the race took a turn for the worst. The winds started to howl, making the track miserable to ride. Two slot canyons provided a brief sanctuary from the invisible force of the wind, but the blowing dust became unbearable as soon as you hit the open areas of the track. My body was in unbelievable pain, something I was trying not to think about at the beginning of the race. I tried to limit my movements on the bike and be as smooth as possible, because any small mistake I made would cause unreal amounts of cramping, and the pain would only worsen if I crashed.

Up to this point, I hadn’t crashed. But, alas, as I navigated one of the many single track trails, a surprise hole caught me off guard as the trees consumed all of my vision on the narrow course. My rear tire was stuck, and it wasn’t long before the fabled KLR650 showed up and I knew I was about to have a shouting match with Zac. In this instance, I was 100 percent taking up the entire single-track trail and attempting to lift the RX out of someone else’s hole that I just dug deeper. I shouted to Zac, “Go around!”

He yelled back, “I’m too big. I can’t fit!” Eventually, Zac’s impatience got the best of him and sent his KLR careening through the thick overgrowth of the Glen Helen trees.

After spending all of my energy pulling my bike out of the hole, I then reached one of the several rock gardens I had mentioned earlier, groaning at the thought of bouncing off every rock. I then accidentally rode up the embankment, sending myself and the beloved 250RX 15 feet through air and landing on a van-sized boulder, dropping the stoke level to zero.

Woefully, I picked the bike up and made my way around the track in desperate need of a long break.

2:00 A.M (HOUR 16)

Trevor: Everything—and I mean everything—was hurting. Throughout the day, one of the Joshes would tag along on a GasGas EX250 that Josh Fout had brought as a chase vehicle. They were having a blast following me, but it was quite annoying to me. As an Ironman competitor, whenever I would see the smallest sliver of someone else’s light hit a tree, I would immediately pull over and wait for them to pass so that I didn’t hinder their race in any way. But at 2:00 in the morning, it became difficult to tell if it was a competitor or one of my pit crew giggling in his helmet as he followed me. By the time I reached the dreaded silt hill, after 16 hours of riding, it had deepened to several feet of pure silt. I will be honest, every time I got to this section, I threw down the legs and straight up doggy-paddled my way up the mountain holding the bike wide open as the RX plowed its way through the terrain. But, at 2:00 a.m. my body was aching, and as I reached the top, my foot lost its position. I lost my balance and tumbled down the hill into someone’s front wheel. I looked up, and sure enough, it was Josh Mosiman. I stared at him blankly in the pitch black and yelled, “You’re picking up that bike!” and sure enough, he did. I spent several minutes resting my head on the handlebars at the top of the mountain, and once I regained my breath, we got on our way.

4:00 A.M (HOUR 18)

Trevor: By the passing of the witching hour, everything had become a blurry vision. The wind had picked up so badly you couldn’t see 4 feet in front of you. I trudged along and took my longest break in the race just before sunrise. By this time, I had already changed into another set of gear, which in the long run was a mistake. Trying to get out of one set of gear and into another after this long day was more of a chore than I expected. Then, I laid down in the back of Josh’s van with a blanket over my face to escape the life-sucking wind for 30 minutes. I was unable to fall asleep, but our test rider/friend Ernie Becker will tell you otherwise, as he woke up at 2:00 a.m. and decided to drive out and show his support, since he had nothing better to do in the middle of the night.

6:00 A.M (HOUR 20)

Trevor: The sun had risen, and there were four hours left in the race. At this point, we had switched it up to doing just two laps and then a break, trying to play the long game as much as possible. At 6:00 in the morning, I was greeted with a cold plate of pancakes that I wasn’t eager to eat. I didn’t feel like taking off my helmet and just ate them sitting in a beach chair with the wind trying to knock me over.

8:00 A.M (HOUR 22)

Trevor: My body was crushed, but thankfully the CRF250RX was holding up incredibly well. The only thing we had changed was oil once and the front number plate when it became daytime again. Zac and I were trying to ride as little as possible so that I didn’t go out and have a catastrophic failure with just two hours left. At some point during the night, the pit crew had accidentally spilled the beans about what place I was in, and, unfortunately, I was within earshot. I was in fifth. After Zac had passed me in the middle of the night during my little trail blunder, I had made my way down to sixth. Knowing this information, I didn’t want to try harder. I knew I could play it safe since seventh place was several laps behind me. Ultimately, I didn’t care how I finished, but I was appreciative that I could take a longer break without getting passed.

10:00 A.M (HOUR 24)

Trevor: The final lap was underway. Zac and I had strategized to leave just after the leaders made their way around for another lap so that we wouldn’t have to do another two laps to finish the race. Sure enough, when we pulled into view of the finish, the white flag came out. We stopped with just a few turns left in the race to wait for the leaders to come around once more because we didn’t need to ride the course one more time to hold our positions.

Eventually, the valiant team of Tyler Nicholson, R.J. Warda, Thomas Dunn and Clayton Roberts came in to grab the checkered flag, and the handful of people who didn’t want to do another lap followed in shortly. There were hundreds of people at the finish line cheering, and it took several weeks before it dawned on me just how crazy it was. I’m not much of an alcohol guy, so a bottle of sparkling cider awaited my finish.

Looking back, it was easily one of the most insane things I have ever done, and I couldn’t have done it without the help of both Josh Mosiman and Josh Fout. I also had plenty of support from the SOFLETE Marine crew (Seth Barnez), my parents who came out, and the Bushnell family, who camped right next to our pit. Now that I have one 24-Hour Ironman finish under my belt, the question is, would I do it again? Surprisingly, yes. As grueling as this story sounds, I look back fondly on the moments when I was having fun. But, be warned, it is not for the faint of heart. It’s for those who are dedicated to finishing a task and/or those who are easily persuaded.

TREVOR’S 24 HOURS OF PAIN: THE VIDEO

Comments are closed.