MXA TURNS A HUSQVARNA TX300 ENDURO BIKE INTO A TC300 MOTOCROSSER

Click on images to enlarge

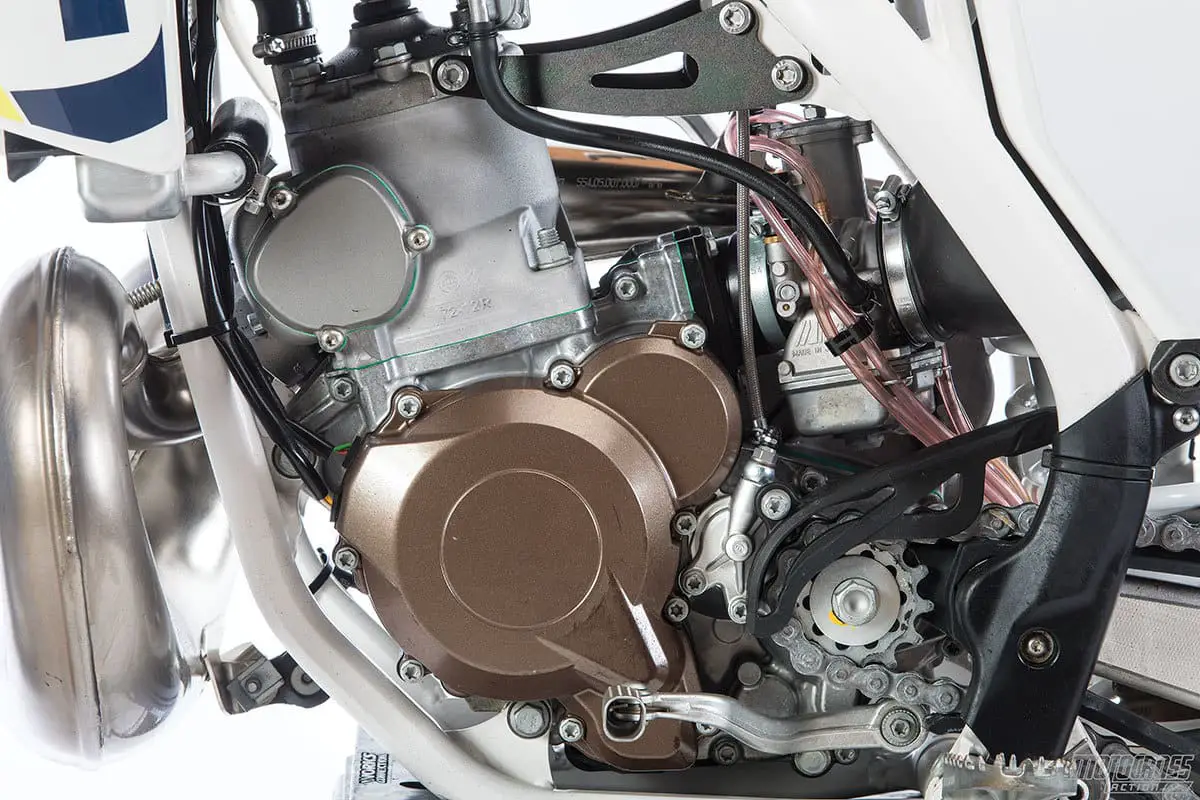

The 2017 Husqvarna TX300 is like a motocross bike with a kickstand, 18-inch rear wheel, over-size fuel tank, heavier flywheel, electric starter and a semi-wide-ratio transmission. It’s a good all-around off-road bike, but the MXA wrecking crew wasn’t interested in the bike for its ability in the woods. We wanted to unleash its motocross potential. Neither Husqvarna nor KTM produces a motocross version of their 300cc two-stroke machines. We wanted to rectify that by taking apart a TX300 and putting it back together again in full motocross regalia.

EVERY RIDER FROM BEGINNER TO PRO FELT THE TC300 HAD A VERY USER-FRIENDLY ENGINE. THEY DID NOT, HOWEVER, COLLECTIVELY CHOOSE THE TC300 ENGINE OVER THE TC250.

To be transparent, Vets and Novice riders did not fare well with the all-new Husky TC250. Riders spoiled by the easy-to-use, planted feel of four-stroke power were caught off guard by the explosive TC250 muscle. Instead of twisting the throttle and the rear end sticking to the ground, the TC250 felt like it was lifting up and blasting off. The TC250 was a wild ride that our Intermediate and Pro test riders adored, but for everyone else there had to be a better combination of power and usability than the standard-issue TC250. We are not backpedaling on our glowing opinion of the TC250. It is the best 250cc two-stroke on the market (alongside its twin brother, the KTM 250SX). It has great power, handling, suspension, brakes and clutch. So, what gives? We wanted to build a two-stroke that was easy to ride, had a broad powerband, and got the job done without all of the Cape Canaveral fireworks.

Since we had a TX300 and wanted a TC300, this is how we got one.

(1) Kickstand. A kickstand on a motocross track is just added weight. Either way, you will still need a bike stand to check spokes and tire pressure, change wheels and lube the chain. If you don’t like picking your bike up to put it on the stand or have trouble doing so, look into the Power Lift motocross stand that many of our testers have grown to love.

(2) Rear wheel. The TX300’s 18-inch rear wheel gives the bike some added plushness in a straight line but starts to fold over in flat corners. The rear end wallows under acceleration with the 18, so we changed it out for the more consistent and familiar feel of a 19-inch rear wheel.

(3) Gearbox. The final ratios between first through fifth on the TX300 are similar to the TC250’s gearbox. The TX’s semi-wide-ratio transmission is better—and worse—than the TC250’s. It is better in the sense that there is a larger gap between second and third gear. With the TC250, second and third are too close, which makes for awkward shift points. It is worse due to the big gap between third and fourth, while our testers never reached sixth gear on a motocross track. For a motocross track, fourth gear just needs to be brought closer to third by a hair, while sixth gear is just a paperweight and needs to be taken out.

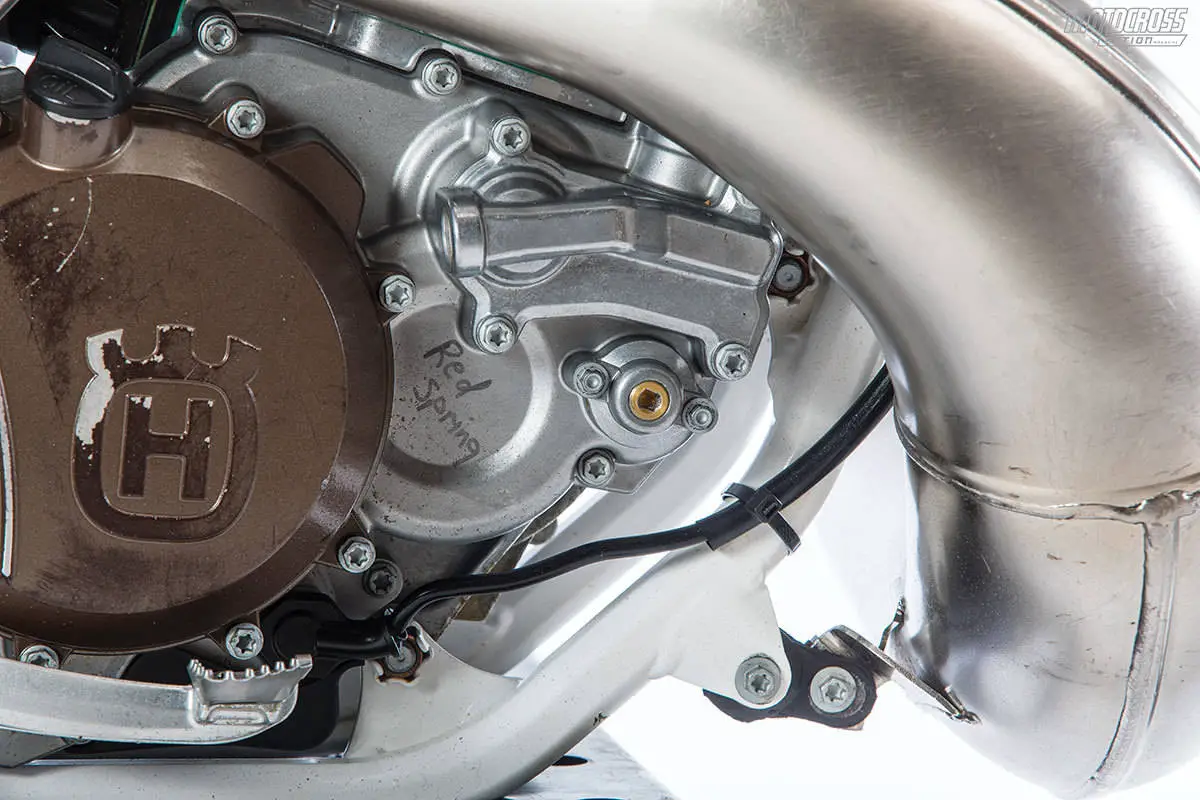

(4) Flywheel. To get a more tractable feel and broader power on the 250cc machine, we stuck with the heavier flywheel from the TX300. The stock TC250 motocross version would benefit from this.

(5) Gas tank. We removed the large 2.65-gallon tank from the TX300 and replaced it with the TC250’s 1.85-gallon tank.

(6) Electric start. If you think that a few pounds would deter us from keeping the TX300’s electric starter, you better think again. The TC250 weighs 211 pounds in stock trim, while our homemade TC300 weighs 218 pounds.

(7) Suspension. The TX300 came with WP AER 48 forks, but they were valved on the soft side for use in offroad conditions. Since they are air forks, we could make them usable by adding more air, but that would just be a Band-Aid fix. The valving wasn’t progressive enough on the TX forks. They settled into the bottom of the stroke and delivered a harsh feel. Plus, when we stiffened the forks, the front end didn’t balance well with the soft shock, even though we were all the way stiff on the shock’s compression. So, we made it easy and put the TC250 shock and forks on our TX300.

WE FOUND AN EASY YET STRANGE SOLUTION TO OUR JETTING PROBLEMS. THE MANUAL SAID THAT WE SHOULD RUN A GAS-TO-OIL RATIO OF 60:1. THAT IS NOT A TYPO.

When our TC300 transformation was complete, we had riders of all ages and skill levels ride the bike. We had our TC250 on hand for back-to-back testing and got feedback about what the riders liked and didn’t like. Here is a breakdown of what our testers thought about our TC300.

Every rider from beginner to Pro felt the TC300 had a very user-friendly engine. They did not, however, collectively choose the TC300 engine over the TC250. For faster riders, the TC300 lacked the aggressive hit and light throttle of the TC250. Conversely, the TC250 lacked the bottom-end grunt of the TC300. Our Pros didn’t mind that the TC250 engine signed off early, because they were willing to hammer new gears all the time. They had the skill and youthfulness to choose power over usability. Still, each rider who chose the TC250 did say that he wished the TC250 were more like the TX300.

The Vet and Novice riders found that the TC300 was a much better race machine than the TC250. To a man, they turned in more consistent lap times and had more fun in the process. The big plus of our TC300 hybrid was its extremely linear powerband from the bottom to the top end. There was no need to use the clutch out of corners. It could chug second and third gear with no problem, whereas the TC250 needed some clutch work. On the TC300, slower riders didn’t have to shift if they didn’t want to. The top end would go flat, but it would never fall on its face and push the weight of the bike forward. Keeping the weight back is important, because it keeps the rear end planted and the chassis balanced. When the weight moves forward on a two-stroke, it frees up the rear wheel and puts the weight on the front end, making the bike less stable at any speed.

When we first got our TX300, the jetting was very rich. We spent most of our time testing jetting. It became a weekly ritual, as temperature changes or an ill wind blowing off the desert would make the Mikuni go wonky. We were able to get the jetting close with the help of JD Jetting. But, shockingly, we found an easy yet strange solution to our jetting problem. In the manual, it says to run a gas-to-oil ratio of 60:1. That is not a typo. We were shocked.

To tell the truth, we didn’t want to do it. And, we could tell that Husqvarna was even more nervous than we were. But, the Husky mechanics said that the factory engineers back in Austria were adamant that it would work (they also told us that they hadn’t tried it themselves, which only increased our trepidation over such a lean mixture). But, Husqvarna assured us that if we blew up our engine with the factory-recommended 60:1 ratio, they would put all-new parts in our bike. So, we put the jetting back to stock and drew straws to see who would ride the 60:1 time bomb. The bike ran perfectly. No hiccup or sputter.

The problem for both Husqvarna and KTM is that no one ever reads the owner’s manual. Add to this the old-school mentality of most two-stroke riders, who are stubbornly resistant to change, and we don’t see a lot of 250SX or TC250 owners risking their engines on a single line in a book. Plus, they don’t have factory mechanics promising to rebuild their engines if they are wrong about the fuel mixture. Nevertheless, the ratio is right. It worked and made us change our opinion about the Mikuni-for-Keihin swap of 2017.

ON THE TRACK, OUR BACKYARD TC300 FELT HEAVIER THAN THE TC250—HEAVIER THAN CAN BE ATTRIBUTED TO THE 7-POUND WEIGHT DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE TWO.

On the track, our backyard TC300 felt heavier than the TC250—heavier than can be attributed to the 7-pound weight difference between the two. While our Vet and Novice riders didn’t notice much of a difference, the faster riders were quick to mention that when picking a line or maneuvering, the TC300 felt heavier. No matter how you slice it, 7 pounds is significant, but why didn’t the slower riders notice the weight, while the faster riders did? That’s simple. The 300cc engine produces a different kind of power than its snappy 250cc brethren. The bigger engine’s torquier vibe gives the bike a heavier feeling. Think of it this way: a 2017 KTM 450SXF weighs less than most Japanese 250Fs, but it still feels heavier on the track due to the power pulses of its bigger displacement.

When you add in the chug effect of the larger displacement and heavier flywheel, the rear end of the TC300 sticks to the ground like glue, whereas the TC250 hits hard, jumps at the slightest hint of throttle and feels light as a feather. Of course, the main reason the TC300 feels heavier is that 7 pounds is 7 pounds, no matter what scale you use. The biggest difference in handling goes back to the heavy feeling of the bike. Many of our test riders, even the Pros, loved the four-stroke-like tractability of the TC300. It was foolproof. It didn’t matter how hard you were on the throttle, the rear end would squat, track to the ground and follow the front wheel like clockwork every time, almost like traction control. It was the best of both worlds—the good-handling traits of a four-stroke mixed with two-stroke flair.

The switch from the offroad TX300 suspension to the TC250 suspension components allowed our testers to access the full potential of the TX300 on a motocross track. It is no secret that we love the WP AER 48 forks and WP shock combination, with the bonus that we could run the TC300 suspension settings a hair softer than on the TC250 due to the smoother power delivery.

Should Husqvarna put a TC300 motocross version in its 2018 lineup? It is easy for hardcore motocrossers to say yes, but where would riders race it? The royal flummox of the AMA’s unequal four-stroke displacement rules have made two-strokes poor second cousins in the motocross world. But, the point is moot, because the idea of a TC300 isn’t about fitting into the AMA’s structure; it’s about finding the perfect two-stroke for your needs and wants. We are willing to bet dollars to donuts that the average Husqvarna TX300 buyer is 35 to 55 years old and, if Husky built a 2018 TC300 model, the age wouldn’t creep down one iota. This is a Vet machine, and Vets can race whatever they want in the Vet class. Plus, the question of whether unique engine sizes can be successful has already been answered by the KTM 350SXF and KTM 150SX. These orphan bikes are extremely popular.

SHOULD HUSQVARNA PUT A TC300 MOTOCROSS VERSION IN ITS 2018 LINEUP? IT IS EASY FOR HARDCORE MOTOCROSSERS TO SAY YES, BUT WHERE WOULD RIDERS RACE IT?

Is there a case for a production TC300 as a companion piece for the TX300? Sure there is. The rise in popularity of two-strokes over recent years means that it is a seller’s market. By building a TC300, Husqvarna and KTM could plug the gaps in the marketplace. Think back to the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. The TC125 is too slow, the TC250 is too fast and the TC300 is just right.

Comments are closed.