MOTOCROSS: AS IT IS, WAS AND EVERMORE SHALL BE

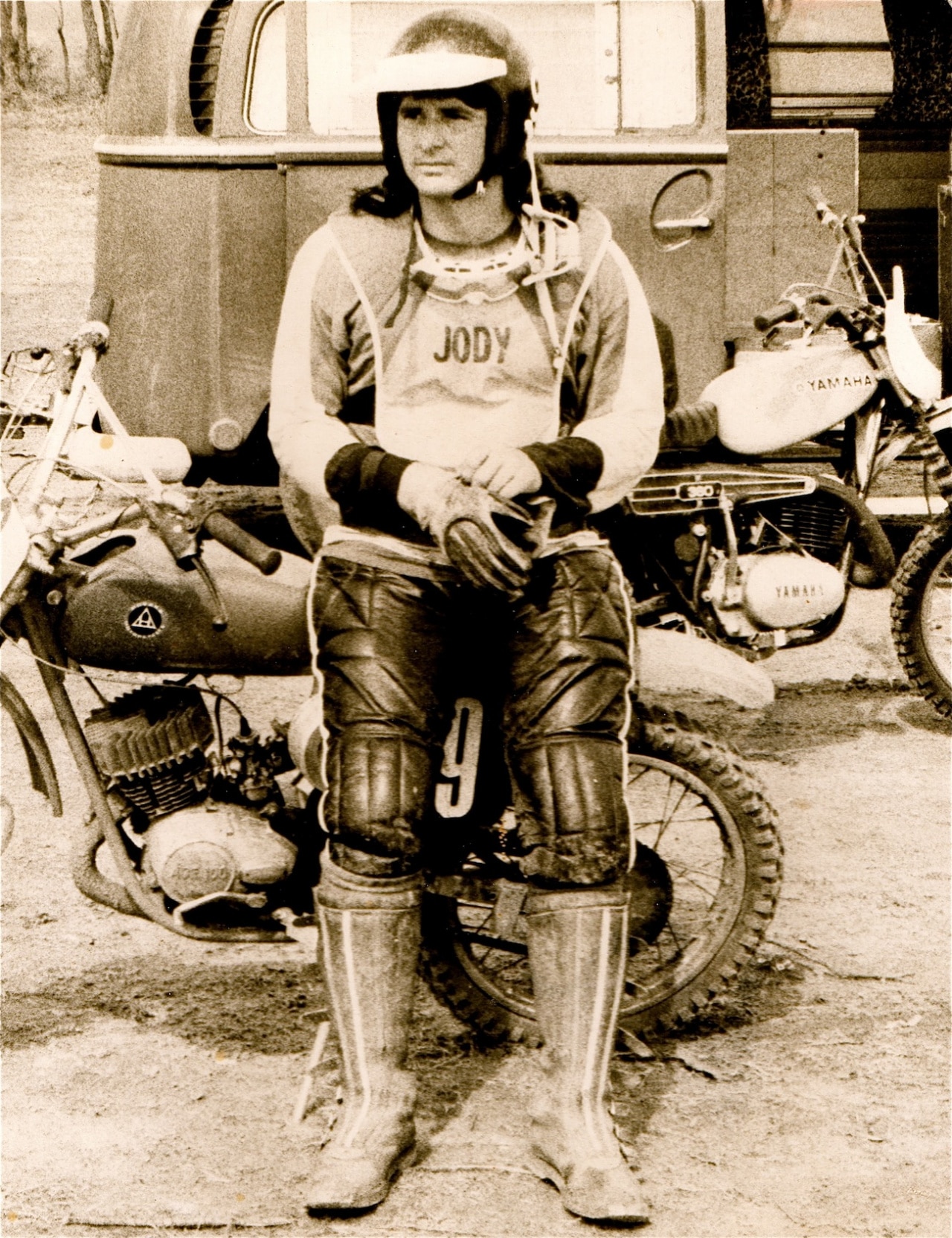

This is how a motocrosser’s dressed in 1971. The leather Full Bore boots were not backed up by shin guards or knee braces, the only knee protection came from the quilting on the leather pants and the open face helmet was mated to a duckbill visor, Carrera goggles and a Jofa mouth guard.

This is how a motocrosser’s dressed in 1971. The leather Full Bore boots were not backed up by shin guards or knee braces, the only knee protection came from the quilting on the leather pants and the open face helmet was mated to a duckbill visor, Carrera goggles and a Jofa mouth guard.

BY JODY WEISEL

This is a story about motocross as it was; personal; heart felt; and anecdotal. Today’s racers give little thought to the roots of our sport. Why sugarcoat it! They care little about anything that came before Snap Chat, iPods and ear buds. No shame. No sweat. No worries. They know what they know—and nothing more. Motocross, as they know it, is as it is—fully grown and developed.

That wasn’t so back-in-the-day (referring to the Golden Age from 1968 to 1976). I know, perhaps better than anyone, because the late ‘60s and early ‘70s were a wonderful time for me to start my career as a motorcycle racer. I’ll carry those warm memories for the rest of my days. I know that you may doubt my version of the past, but you should know that I was at Rio Bravo when Jimmy Weinert became the first American to win a Trans-AMA event at Rio Bravo. I was at Livermore when Roger DeCoster’s front forks broke off. I was in San Antonio when Bob Hannah “let Brock bye” (and I shot the famous photo). I was in New Orleans when Kent Howerton beat Gary Semics for the 1976 500 title at the “Battle of New Orleans.” I was at Carlsbad when Marty Moates became the first American to win the USGP. I was at Anaheim Stadium when Marty Smith tried to race a CR125 in the 250 class. I was at Saddleback the day Jim West was killed. I was at Vimmerby, Sweden, when Danny LaPorte clinched his 250 World Championship. I was there when the “Magoo Double Jump” got its name. I was at Huron the day David Bailey got hurt. I was there when Jeremy McGrath rode his first 125 Novice race. I was there the first time Mike Alessi tried to ride a 50 and I was 25 feet away when he stood on Ivan Tedesco’s bike at Glen Helen. I knew (and miss) Peter Lamppu, Wyman Priddy, Rich Thorwaldson, Jim West, Gaylon Mosier, Feets Minert, Tony Wynn, Pete Snorteland, Donny Schmit and Bob Elliot. I was lucky to be around at the beginning and even luckier to still be around today. I have witnessed motocross as it is, was and evermore shall be. This my story.

I came to motocross the traditional way—via the Boston Red Sox. That probably needs some clarification. Let me just say that in the decades following the end of the Second World War, America was a bland place to live in—exceedingly homogenized. The individual sports we know and love today, didn’t exist (or they existed so far on the fringe that only the cultish knew of them). Motocross, surfing, snowboarding, karting, skateboarding, BMX, skydiving and wakeboarding hadn’t made it to the American psyche in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The post-war years were devoted to maintaining, actually reestablishing, the status quo—and I was child of that era.

THE COLD WAR PERIOD OF REGIMENTATION HAD JUST BEGUN; SCHOOL CHILDREN LEARNED TO “DUCK AND COVER” IN CASE OF NUCLEAR ATTACK; AND WAR-WEARY MEN SLAVISHLY DEVOTED THEMSELVES TO STICK-AND-BALL SPORTS.

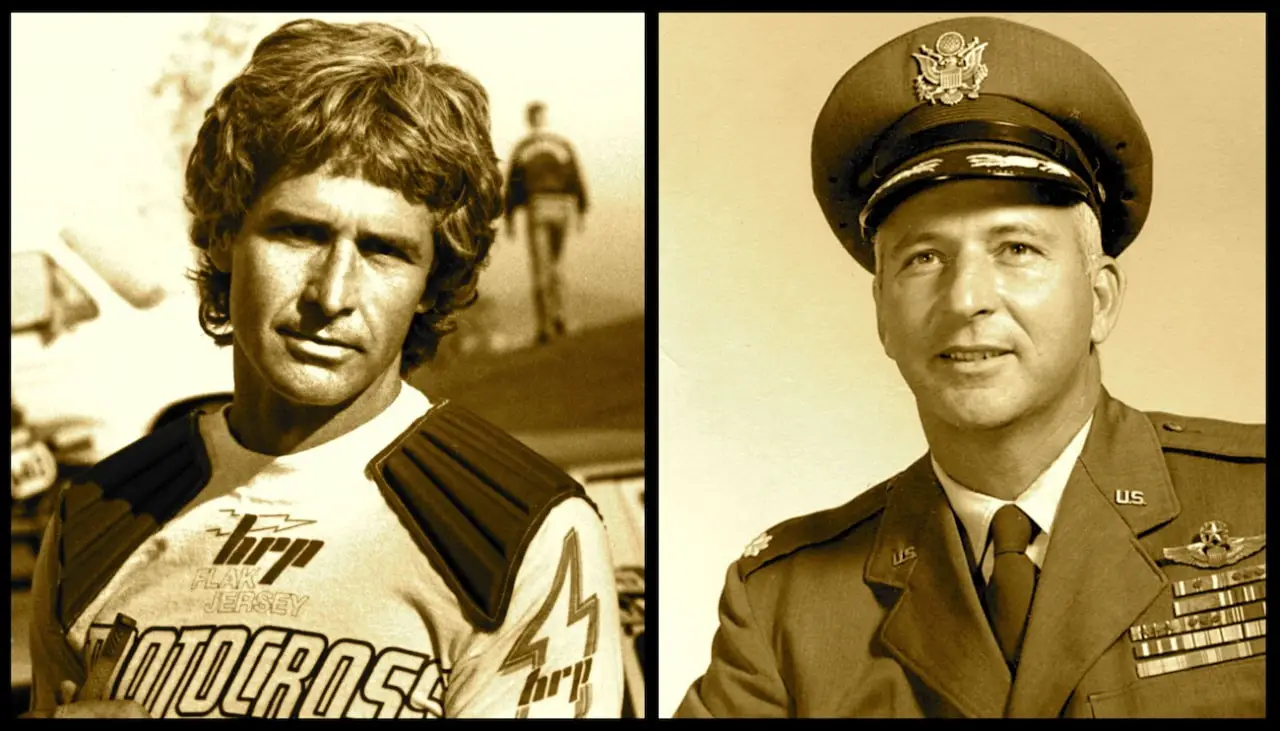

Jody and his dad in their uniforms.

Jody and his dad in their uniforms.

The Cold War period of regimentation had just begun; there was a mass migration to the suburbs; young couples all bought the exact same house (in our personal Levittowns); school children learned to “duck and cover” in case of nuclear attack; radio station only played 40 songs (the top 40); moms collected Blue Chip Stamps in hopes of winning a toaster; there were only three TV networks playing on the Dumont; and war-weary men slavishly devoted themselves to stick-and-ball sports.

Which is not, as you might think, where the Boston Red Sox enter the picture. Nope. Instead, flashback to March 22, 1945, as a four-engined Boeing B-17 bomber named “Buckeye,” winged its way towards Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. According to the official U. S. Army Air Corps debriefing after the mission, the pilot of Buckeye reported that:

“At that moment I felt a whumpf right below us. A piece of flak slammed into the number three engine and smoked poured into the cockpit. A piece of flak cut through the navigator’s flying suit, ricocheted off the instrument panel, tripped the bomb switch and released the bomb load. Then, Buckeye lost its number four engine. The crew jettisoned all movable equipment, including the 1800-pound tail turret. We landed safely in Ridgewell, England, with only the two left engines.”

My father was at the controls of Buckeye that day and his report was very understated proven by the fact that he was sent to a hospital in Merville for burns and a wounded arm. His parents, my grandparents, got a telegram that stated:

“The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son Lt. Charles A. Weisel was wounded in Germany, 22 March, 1945.”

And that is where the Boston Red Sox come in. Before WWII my father was an aspiring professional baseball player. War changed that. He never returned to the field of dreams. After WWII my father stayed on as a professional pilot in the USAF—flying through two more wars. As a kid, our family lived on the Dew Line in a series of SAC (Strategic Air Commnand) air bases, worshipped at the right hand of General Curtis Lemay, understood that my father was expected to sleep at the end of the runway (next to his fully loaded plane) for one week out of every month and that I would grow up to be a professional baseball player (per my father’s wishes). Like millions of other American kids, I was going to fulfill the dreams that Tojo, Goering and Mussolini had ruined for my father.

IT’S NOT SO HARD TO UNDERSTAND WHY COUNTERCULTURES DON’T SPRING FROM THE LOINS OF MEN WHO HAD JUST SPENT FOUR YEARS KILLING OTHER HUMAN BEINGS TO PRESERVE THE STATUS QUO. WHEN DEATH IS THE ALTERNATIVE—THE STATUS QUO LOOKS JUST PEACHY.

On March 18, 1945, Jody’s dad flew “Los Angeles City Limits” to bomb the Berlin railroad station. Four days later, he was wounded in “Buckeye” over Germany.

Baseball was important to Americans in the bland 50’s. Post-war America wasn’t a rebellious place. People weren’t eager to cut their own swath through life. They wanted everything to return to normal; they wanted to fit in; they wanted to enjoy what they had won; and what others had given their lives for.

It’s not so hard to understand why countercultures don’t spring from the loins of men who had just spent four years killing other human beings to preserve the status quo. When death is the alternative—the status quo looks just peachy. In my father’s B-17 squadron alone, the 381st Bombardment Group, Nazis Me109’s and Focke Wulf Fw190’s had shot down 132 planes—at a cost of 1400 lives. As strange as it may sound, those men died for the right to play baseball in a free country.

Baseball was important to me also. I knew all the stats and idolized Warren Spahn, Enos Slaughter, Mickey Mantle, Stan Musial and Whitey Ford. Minicycle parents are the distant offspring of Little League parents (and Little League itself was the product of a desire to get the youth of America off on the right foot via the self-correcting powers of America’s game). My father wasn’t a screaming Little League parent; instead he was a task master. He drilled me endlessly on how to hit a curve ball, how to hit a fast ball, how to get hit by a fast ball (according to my dad taking one in the ribs was as good as hitting a Texas Leaguer into left field). When my father wasn’t foiling the Red Menace as a Air Force Colonel in some classified location up by the Arctic Circle, he was smashing ground balls at me at quasar (a word which wasn’t in the lexicon back then) speed.

“THAT’S NOT A SPORT!” MY FATHER REPLIED. AND, I THINK HE WAS RIGHT—AT LEAST TO THE THINKING OF THE AMERICANS OF THE COLD WAR ERA.

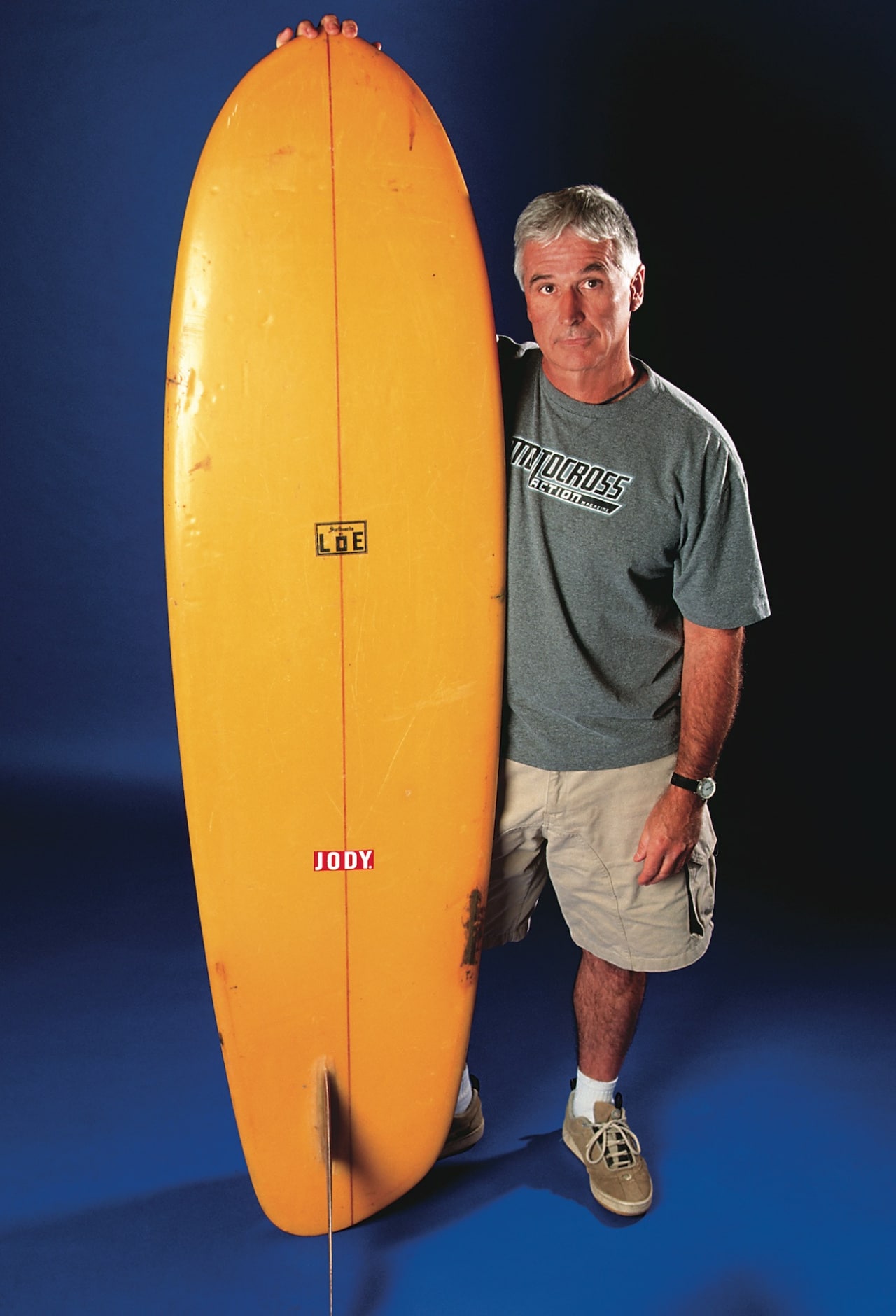

Jody playing around nose riding some small surf back in 1967.

Jody playing around nose riding some small surf back in 1967.

And, I played baseball every day of my young life: Little League, Pony League, American Legion, pickup games or against a wall by myself. I smelled like Neat’s Foot oil and my Wilson glove never left my hand, except to be replaced by a 33-ounce Louisville Slugger. It’s no surprise that I was a successful baseball player, after all I was the son of a legacy. There were moments of glory, like when I pitched three no-hit innings in relief in the Little League World Series regional play-offs against Canada (we lost). I batted .466 in the Pony League and played in their World Series play-offs (we lost). And, I made it on to the Boston Red Sox radar. One of my father’s old professional baseball cronies, a Red Sox third baseman named Ted Lepcio, was working as a Bosox scout and he came out to the house one night with a contract for me to sign.

Oh, don’t get me wrong, it was a true-to-life Red Sox contract, but not a ticket to the Big Show. No sirree! First of all, at the time, I was only 15-years-old. Second, I had no experience with big league pitching. Third, I would be sent to upstate New York to play for the minor league Wellsvillle Red Sox for seasoning. Fourth, the Red Sox organization was offering me $6000 a year. Or, was it $7000? I don’t remember, because I walked out of the kitchen. I told my father, and the Boston Red Sox’s Ted Lepcio, that I had no intention of playing baseball—that I was switching sports.

“What are you switching to?” ask my father. Now, it may seem obvious to you that I was going to tell my father that I wanted to be a motocross racer, but silly rabbit, motocross was not yet a gleam in Edison Dye’s eye. This was the early ‘60s. There was no motocross in America when the Boston Red Sox’s third baseman came calling to my family’s kitchen table that night.

“Surfing,” I said.

“That’s not a sport!” my father replied. And, I think he was right—at least to the thinking of the Americans of the Cold War era.

AS THE PROGENY OF A DASHING ARMY AIR CORP PILOT AND ROSIE THE RIVETER (MY MOTHER WORKED IN A FACTORY THAT MADE THE BOMBS THAT MY FATHER DROPPED ON ADOLF WEIL’S HOUSE), I WAS THE BENEFACTOR OF THEIR BLOOD, SWEAT AND TEARS.

Jody isn’t playing around with this Rincon grinder. He’s cranking it off the bottom.

Jody isn’t playing around with this Rincon grinder. He’s cranking it off the bottom.

Surfing was not a sport. It was defiance (and need I remind you that post-war America was not a seditious place). But, I wasn’t born during the Second World War—I was a baby boomer. I was spawn of the Greatest Generation—not the real deal. As the progeny of a dashing Air Corp pilot and Rosie the Riveter (my mother worked in a factory that made the bombs that my father dropped on Adolf Weil’s house), I was the benefactor of their blood, sweat and tears. But, all I knew about the Second World War I learned from “Sgt. Rock” comic books. I can distill my military knowledge into this simple treatise: German machine guns go “Brappp-brapp,” Japanese machine guns go “Brudda, brudda, brudda” and American machine guns go “Rat-a-tat-tat.”

In many ways, my father was right, Surfing was not a sport back in the early ‘60s. It was something more sinister. It was a teenage treatise against the conformity of post-war society. It was a primal scream against the ticky-tacky houses, Cadillac Fleetwoods, gray flannel suits, picket fences, burr haircuts and weekly Ed Sullivan TV shows (not to mention Topo Gigio). If you weren’t around back then, you can’t fully understand how bland America was in the ‘60s, but we are talking about a whole country full of people who didn’t know that Liberace was gay (Rock Hudson I can understand).

Surfing was something wholly original to the sport’s world of the ‘60s—it owed no allegiance to the past. It belonged, lock, stock and barrel, to the young. Surfing wasn’t tied into our parent’s lifestyles in any way. Surfers had their own lingo (as all cults must), fashion sense (striped shirts and huarachi sandals), hair styles (long with a lemon juice drip) and heroes (mine was Mickey Dora, not that goody-two-shoes Phil Edwards like everybody else).

Surfing was what every parent in American feared the most (at least parents who lived in affluent beach communities). It was a world totally alien to what they had sacrificed so much for. Surfing was based on an idyllic and pointless pastime. It was the anathema of the Puritan ethic. It had no redeeming social value. It had undercurrents of jungle beat music (Dick Dale) and it could only lead to a life of idleness, fraternization with beach bums and wanton sexuality. Cowabunga!

IT’S STRANGE HOW ALL NONCONFORMISTS DRESS, ACT AND SPEAK THE SAME. IT’S ALMOST EERIE. THERE MUST HAVE BEEN AN ORIGINAL REBEL IN EVERY BREAKAWAY GROUP, BUT HE PROBABLY REBELLED AGAIN AS SOON AS TOO MANY FOLLOWERS JOINED HIS MOVEMENT.

Jody with his sole remaining asymetrical surfboard. It was a long pintail to the right and round tail performance board to the left—with rail shapes that differed on each side.

Jody with his sole remaining asymetrical surfboard. It was a long pintail to the right and round tail performance board to the left—with rail shapes that differed on each side.

It’s strange how all nonconformists dress, act and speak the same. It’s almost eerie. There must have been an original rebel in every breakaway group, but he probably rebelled again as soon as too many followers joined his movement. I didn’t invent the surfer look, lingo or cultural mannerisms. I adopted them. In reality, I co-opted them. Stole them like a shoplifter stealing a cheap suit. I tried it on and it fit—so I ran with it. I became a surfer instead of a baseball player because I didn’t want to wear leggings and a cap. That wasn’t for me. I wanted to wear sandals and baggies. Yes, Virginia, I know now that I simply traded one uniform for another, but that second set of clothes shocked all the good decent people of the Harper Valley PTA. And I liked that.

The Wellsville Red Sox didn’t get their hooks in me, but over time I was gobbled up by the surf industry. Sadly, surfing wasn’t about freedom for very long—it got greedy as it got popular—and surfing boomed in the counterculture ‘60s thanks to the Wilson brothers and their partners in crime, Jan and Dean. It should come as no surprise that once a sport becomes popular it becomes just as insidious as any other big biz. Surfing and I grew more commercial with each passing year—each of us lining our pockets with filthy lucre. I became a contest surfer, plying my trade for the Dewey Weber Surf team; traveling to the lesser known surf niches; spreading the word like a surfing Johnny Appleseed. Maine, Massachusetts, Virginia, Florida and Texas surfers owe me, and the other corporate surfing sell-outs, a debt of gratitude. We were the first to surf our Weber V-Bottoms, Performers and SuperWides in the isolated backwaters of America.

This Dewey Weber Performer hangs in Jody’s living room.

This Dewey Weber Performer hangs in Jody’s living room.

Big surprise! There is no purity on the pro surfing scene—and, at the time, very little money. Surf contests are stupid—and I say that as someone who won them. They engender, nee’ reward, idiotic, jerky, soulless surfing. I didn’t quit the contest scene so much as I turned my back on it. I stayed at my home beach and surfed for fun. It wasn’t as glamorous back on my dingy local beach, not that the life of a vagabond surfer in the ‘60s was all that glam, but I made up for it by concentrating on the spirit of surfing. I was rebelling against my own rebellion. I designed my own surfboards, built them myself in the backyard of my beach-side A-Frame (the second most nonconformist of all housing designs—after those awful Buckminister Fuller dung heaps) and lo-and-behold sold out again to an enterprising surfboard manufacturer who was willing to mass market my radically unusual asymmetrical surfboard designs under his logo.

I could hardly believe that the same kid who refused to sell his soul to the Wellsville Red Sox, was suddenly a two-time sellout. First, I became a herky-jerky contest surfer doing dog-and-pony tricks in front of bunch of judges, who I wouldn’t invite over to my house if I was serving dog food, and, then I allowed some blue suit businessman, who didn’t surf, to take my wondrous asymmetrical works of art and pop them out like so many G.I. Joe dolls. I was a surfing whore—twice over.

NO WAVES. NADA SURF (NO, NOT THE BAND). ZERO WAVES MEANT MAXIMUM BOREDOM. HO-HUM. SIESTA TIME. ONE WEEK. TWO WEEKS. THREE WEEKS.

Jody’s Super Rat was like no other. He never stopped developing it…until the day he stopped racing Hodakas.

Luckily, two incredible things happened to me at this juncture in my life (no, the Red Sox didn’t call asking me to reconsider). First and foremost, asymmetrical surfboards were way too counterculture for the wanna-bee Wilbur Kookmeyers that had glommed on to surfing after “Gidget.” My first royalty check, “blood money” as my less piggish surf buddies called it, was for handful of Asymmetricals. There was never another check because it turned out that men in blue suits don’t want to make surfboards that they have to explain in detail to their customers. My hydrodynamic genius was misunderstood. Worse, yet, as my surfboard empire crumbled, the surf went flat. No waves. Nada surf (no, not the band). Zero waves meant maximum boredom. Ho-hum. Siesta time. One week. Two weeks. Three weeks. The surf was small, choppy and blown out—what we derisively called “one-foot, chop-to-bottom.”

Then it happened! I could hear the roar of the surf, but there wasn’t any surf. Even more confusing, the rumble was coming from the dunes—not the ocean. Suddenly, the most beautiful thing I had ever seen, blasted over a sand dune and down onto the beach. It was a Sachs 125. Now, decades later, I know how ratty that Sachs-engined machine was, but with my mind numbed by weeks of nothingness…it was the sweet nectar of the machine age.

MY MESSENGER WAS A BEACH KID NAMED JIMMY GATES. I KNEW HIM. I SURFED WITH HIM. BUT, I HAD NEVER SEEN THE GREASE-STAINED SIDE OF HIM. HE HAD FOUND A WAY TO BEAT MOTHER NATURE—IT WOULD NEVER BE FLAT AGAIN.

The first turn at Mosier Valley Raceway in Texas in 1974.

The first turn at Mosier Valley Raceway in Texas in 1974.

I didn’t discover motocross. No one does. It doesn’t strike you like lightning or sting you like a bee. Instead someone brings it to you…or rather rolls it up to your feet. My messenger was a beach kid named Jimmy Gates. I knew him. I surfed with him. But, I had never seen the grease-stained side of him. He had found a way to beat Mother Nature—it would never be flat again. Two days later I bought my own used Sachs…for $300. We became the terrors of our little beach town (population 360).

My A-frame was a block away from the Mayor’s house. I didn’t want to bother my next door neighbors by starting the bike at my house before riding into the dunes, so I would push it down the street and start it in front of the Mayor’s house. After a couple weeks of doing this the Mayor came out one morning in his underwear and said, “Son, they have a race track for those things in the next town. I suggest that you stop riding that thing in front of my house or I will put you in jail.” He was also the Justice of the Peace.

The Mayor wasn’t a sports marketing genius, but he did have the long arm of the law on his side, so Jimmy Gates and I wedged our bikes into my VW microbus and went racing. The track was called “Forest Glades MX.” It cost me a three dollars to enter the 125 class. The only classes were 125, 250 and 500. There was no such thing as Novice, intermediate or Expert. If you raced, you were part of a rare breed—and a very small group. I met John DeSoto that day. Mickey Dora was no longer my role model.

NOTHING SCARED THE FATHER OF A TEENAGE GIRL MORE THAN A GUY WITH A MOTORCYCLE—EVEN IF IT WAS A CZ. IN FACT, CZ’S WERE DOUBLE TROUBLE BEAUSE THEY WERE COMMIE BIKES MADE BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN.

Man does not live by Super Rat alone. Everybody needs a snake pipe Chay-Zed with laid-down shocks.

Man does not live by Super Rat alone. Everybody needs a snake pipe Chay-Zed with laid-down shocks.

The hardest thing about becoming part of a subculture is getting accepted. I wasn’t a motorcyclist. I didn’t know doodly about the lingo, dress or ethics of being a motocrosser. My surfer-ways, which had served me so well in my sun-bleached world, worked against me in the nuts-and-bolts milieu. I didn’t fit in, didn’t own a wrench and the first time I went over a jump, I jumped off the footpegs. Motocross was strange and foreign, but, best of all, it was about as antisocial as a sport could be. All the good folks of America knew about motorcycles they had learned from Hell’s Angel’s movies. Motocrossers were lumped in with the black leather jacket crowd. We were all “carbon monoxide commandos” (to quote Annette Funicello). Nothing scared the father of a teenage girl more than a guy with a motorcycle—especially if it was a CZ. In fact, CZ’s were double trouble because they were commie bikes made behind the Iron Curtain.

To me motocross was surfing squared. It had the same sense of motion; speed; gravity defining lunges; and catapulting crashes. It belonged to a very select group of American youth. There were no old people in motocross in the late ‘60s; no Vet class; no old timers; no grizzled old hands; no adults. We were young and we were in on the ground floor—we could make motocross whatever we wanted—because no one came before. The strange thing is that a motocrosser from today wouldn’t be accepted in the motocross world of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. He’d be rejected for his materialism, professionalism and haughty ways. Motocross then was so different that it almost isn’t the same sport as now—except for the racing part.

How different was motocross in the ‘70s? Very. Need examples?

Chippewa boots were the go-to motocross boot of the 1960s.

Pants: What we call motocross pants today, were called “leathers.” You still hear the occasional old timer referring to his O’Neal pants as leathers, but that’s because in the late ‘60 and early ‘70s motocross pants were made of cowhide (if you were bucks-up, goat skin). The color choices were very simple. Everybody wore black leather pants with a white stripe down each leg. The only exceptions to the rule were riders on Swedish bikes, who wore blue leathers with a yellow stripe. If you were conservative and didn’t want to be too flashy, the stripe was optional.

Shin guards: We didn’t wear shin guards. Torsten Hallman pants, the Hugo Boss of motocross pants, had small plastic knee cups that fit in zippered pockets. Unfortunately, Hallman’s goat skin knees were so fragile that the slightest crash would tear the leather—so we put duct tape over the goat skin to protect it. The other knee protection system of the day was quilting. Pieces of felt were sewn into the hip and knee areas of the leathers in a diamond pattern to provide soft padding in case of a crash.

THESE FIRST-GENERATION MOTOCROSS BOOTS WERE HELD ON BY LEATHER STRAPS THAT YOU BUCKLED WITH METAL CLASPS—THE MORE STRAPS AND BUCKLES, THE COOLER THE BOOT.

What do you do with your old Heckel boots when you are through with them. Jody turned his into a living room lamp.

What do you do with your old Heckel boots when you are through with them. Jody turned his into a living room lamp.

Boots: Plastic wasn’t used on boots in the early days of American motocross. The main ingredient in ‘70s boots was cow—lots of cattle. These first-generation motocross boots were held on by leather straps that you buckled with metal clasps—the more straps and buckles, the cooler the boot. I wore Full-Bore boots…seven straps! If you were avant garde, you could wear Heckels. Heckels were distributed by Bultaco and bore a striking resemblance to the boots that Frankenstein wore—except in blue and yellow.

Helmets: There were only two guys on the planet who wore full coverage helmets in the ‘70s—Tim Hart and Billy Payne (they wore Bell Star road race helmets—flip-down visors and all). The rest of us, wore open-face helmets. Facial protection from 1968 to 1974 was provided courtesy of the Jofa. What a joke! The Jofa had been borrowed from hockey, where it kept a skater from cracking his chin on the ice. Motocrossers adapted it to protect their faces from roost. Maybe it worked for some people, but not for me. The more I gasped for breath, the lower my Jofa would hang. Although I was well protected from a sharp blow against the ice, the rest of my face was exposed. Worse yet, every time I did crash, my Jofa would rip off and the exposed snap would cut a dueling scar across my cheek.

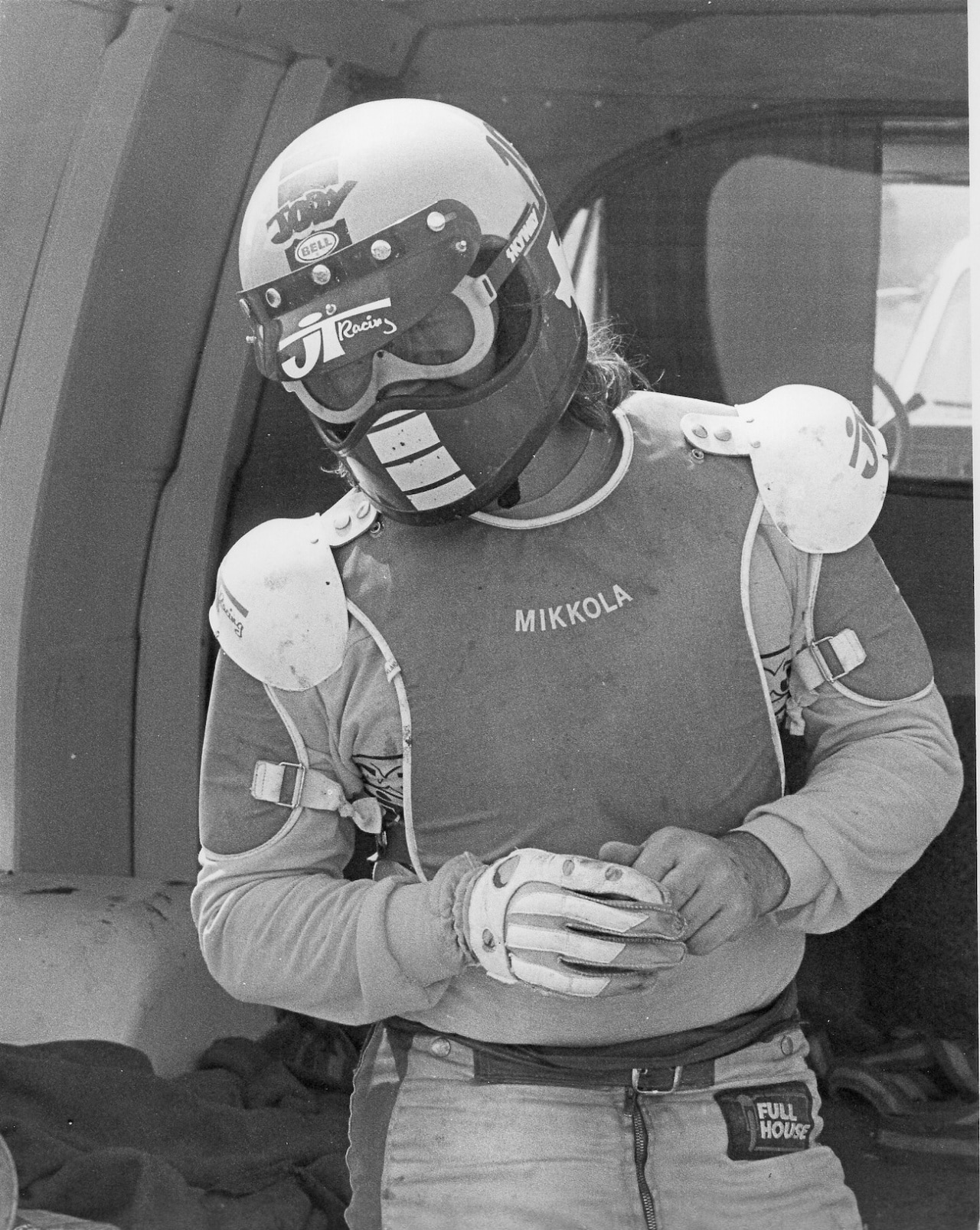

Not every race needed the full garb. Boots, jeans, Jofa and sweatshirt were good enough at local races.

In ‘73, I abandoned the Jofa. Brad Lackey and John Banks had taken to wearing something called the Face Fender. It resembled a vegetable strainer that you snapped across your mug. Made out of plastic, the Face Fender turned an open-face helmet into a full-coverage helmet—as long as you didn’t crash. If you crashed with a face fender on your helmet, it became shrapnel—since the four snaps weren’t designed to take any load.

BELL BEGAN WORK ON A FULL-COVERAGE MX HELMET IN 1975, BUT NOBODY WOULD WEAR IT—UNTIL THAT FATEFUL DAY AT LIVERMORE WHEN ROGER DECOSTER’S FRONT FORKS BROKE OFF OVER THE FASTEST JUMP ON THE TRACK.

The five-snap visor was the ultimate expression of visor coolness.

The five-snap visor was the ultimate expression of visor coolness.

Bell began work on a full-coverage MX helmet in 1975, but nobody would wear it—until that fateful day at Livermore when Roger DeCoster’s front forks broke off over the fastest jump on the track. Before the blood had stopped gushing from the stunned DeCoster’s face, Bell had a hit on their hands. The Bell Moto-Star was an overnight success and The Man was the first customer.

Visors: In the early ‘70s there were lots of visor options. The best was the duckbilll—a very long, unstylish and straight visor. With open face helmets, the duckbill visor could ward off a trip to the dentist—if you ducked your head fast enough.

Full-coverage helmets killed the duckbill, but before they did there were lots of experimentation in the visor world. Malcolm Smith wore a Visor-Vue in “On Any Sunday.” It had two little mirrors in each corner that served two purposes; (1) In a crash, the mirrors did a Jack the Ripper act on your face. (2) The Visor-Vue allowed you to pretend that you could see behind you. In truth, you couldn’t see diddly out of a Visor-Vue—except very shaky sky.

Hallman introduced the Flip-Visor. The Flip-Visor had a rubber band-mounted plastic lens hidden underneath it. Before the start of the moto you flipped the semi-clear lens down to deflect roost off of your goggles. After the first turn, you flipped it up, thanks to rubber band assistance, and had clean goggles. It worked, but it didn’t help you in turn two.

There were vented visors that were suppose to keep the wind from lifting your head up—which negated the fact that most of us were so tired that we wanted our neck muscles to be wind-aided. Another idea was the clear plastic visor. The idea was that when you ducked your head you could look through it—the problem was that a clear visor didn’t block out the blinding sun.

The visor wars came to end when JT popularized the five-snap visor. Five snaps was the hot set-up and JT had the market cornered—so much so that most riders would just stick the five-snap JT visor on their three-snap helmets. It was hip enough—without the extra work.

Those are World War II surplus tank commander rubber goggles slung over Jody’s arm.

Those are World War II surplus tank commander rubber goggles slung over Jody’s arm.

Chest protectors: We weren’t big on protection in the early ‘70s. This was a man’s sport (at least in Europe men were doing it) and we, American teenagers, weren’t going to pansy-out. The dynamics of crash protection was limited to wearing a helmet, after that all we worried about was roost. It stung. The manly among us ignored roost. Kent Howerton claimed that he didn’t wear a chest protector because if he did he would lose the incentive to pass the guy in front of him. Those of us who weren’t as macho, wore a Hallman GP chest protector. It isn’t even a distant relative of a modern chest protector—it offered almost no protection. It, like quilted knees, consisted largely of a soft felt pad you strapped across your chest. The felt pad was spiffed up with a two-tone blue-and-yellow nylon cover.

The Hallman GP chest protector reached its apex at the Superbowl of Motocross when a vitamin company got a handful of stars to wear GP protectors emblazoned with the words “Whoop-De-Chews.” Although it didn’t sell any vitamins, it did sell a lot of Hallman GP chest protectors. We immediately took to removing “Whoop-De-Chews” and putting our own names on the front. It was the first all-out self-promotion in motocross history.

THERE IS NO NEED TO DISCUSS THE GOGGLES OF THE ‘70S. IF YOU WERE ANYBODY IN AMERICAN MOTOCROSS YOU WORE CARRERA GOGGLES (ONLY THE EURO WANNABES WORE BARRUFALDI’S).

Anybody who was anybody wore Carrera goggles in the 1970s.

Anybody who was anybody wore Carrera goggles in the 1970s.

Goggles: There is no need to discuss the goggles of the ‘70s. If you were anybody in American motocross you wore Carrera goggles (only the Euro wannabes wore Barrufaldi’s). It should be noted that Carrera goggles fit well into the American motocrossers lack of interest in protection. Carrera’s barely had a frame, the lens was flimsy, the strap was about an inch wide and there was no air filtration at all.

The Carrera goggle may not sound all that cool, but it was a step up for most of us—we all started with those black rubber goggles that tank commanders wore in the U.S. Army (with electrical tape across the top and bottom of the lens).

Gloves: The coolest glove of the ‘70s was the Tibblin glove. You could always tell a Tibblin owner by the purple stains on his hands—the dyeing process for goat skin had not been perfected in ‘73.

When Jimmy Gates and I rolled into Forest Glades MX track for that first race, we had old helmets, rubber tank goggles, Chippewa boots, work gloves and blue jeans. When the day was over, I was hooked. Not so for Jimmy. He had gotten into a tangle with a guy on a Ducati 160 and said that his racing days were over. Although we still rode in the sand dunes together, I was rapidly becoming more interested in motocross and less in surfing. My weekends were spent at race tracks. And I invested everything I had in racing gear. A new helmet cost $40, boots $50, leathers $60, goggles $10, gloves $5 and my chest protector $25—for the princely sum of $210 I was race-ready.

I did okay on my Sachs, but soon came to realize that I needed better equipment to advance (read, less false neutrals). I sold the Sachs for $350, which most people remember better in a later incarnation as a DKW, and bought a Hodaka. It was a match made in heaven. “The Little Bike That Could” was perfectly mated to my meager talents. I campaigned that chrome toaster week in and week out. I learned to change a ball receiver kit between motos and I got better with each race. Then one day I came home from the races, loaded my surfboards on top the roof of my very cool for a surfer, VW microbus, wedged the Hodie inside and said “adios” to surfing.

Jody’s Volkswagen microbus—surfboards on top and bike inside.

I quit the beach scene cold turkey. I kept one Asymmetrical for posterity, but didn’t set foot back in the water again for 15 years.

I SHOULD MENTION THAT WHEN MY MOTHER TOLD MY FATHER THAT I WAS GOING TO QUIT SURFING AND TAKE UP THE SPORT OF MOTOCROSS, HE SAID, “THAT’S NOT A SPORT!”

I should mention that when my mother told my father that I was going to quit surfing and take up the sport of motocross, he said, “That’s not a sport!”

From that moment on, I dedicated my life to motocross. It should be noted that my level of dedication is a little different from the average Joes. I didn’t drop out of school and hit the AMA National circuit (which by the way hadn’t been formed yet). I’d seen too many surfers take that route in search of the perfect wave—only to end up so poor that all they ever got to see was the wind-blown chop at their local break. Nope. I went to college far from any beach (the University of Texas and later North Texas State University). Going to school in Texas put me in the center of a thriving motocross community. I worked on my Bachelors, Masters and Ph.D. between races at Pecan Valley, Strawberry Hill, Mosier Valley, Paradise Valley, Lockhart (Rockhart!), Rabbit Run, Rio Bravo and Lake Whitney.

For people who took up racing in the ‘80s, ‘90s or, God forbid, the ‘00s, it’s hard to imagine how self reliant a motocrosser had to be in the ‘70s. It was a tough world—made tougher by the newness of the sport. Here are some examples:

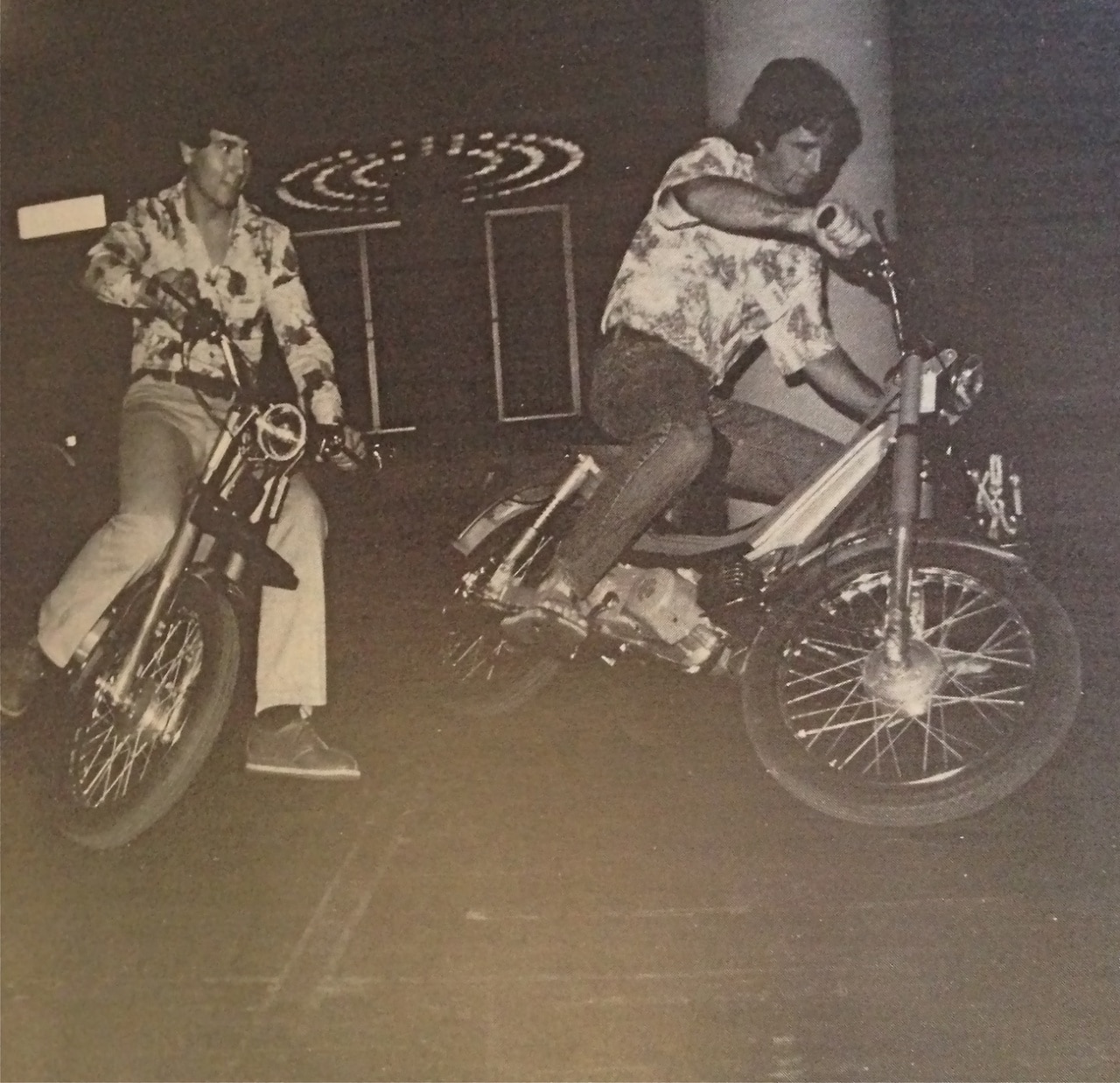

Tony DiStefano (left) and Jody Weisel (right) decided to race mopeds around the Century Plaza Hotel. Yes, they did need a different hotel that night.

Tony DiStefano (left) and Jody Weisel (right) decided to race mopeds around the Century Plaza Hotel. Yes, they did need a different hotel that night.

I remember Tony DiStefano as a 16-year-old kid from Pennsylvania traveling the newly formed AMA National circuit with a Czechoslovakian CZ. When we would ask Tony where he was staying in the next town, he’d say, “The Hotel Dodge.” He meant his Dodge van. He used to come by our hotel rooms to borrow coat hangers out of the rooms (probably why the coat hangars in modern hotels are bolted to the coat rack). We thought he had a lot of clothes to hang up. Not so, he was using the coat hangers as welding rod to patch his CZ frame back together.

I never went racing without a six-pack. No, not beer. I carried six spare spark plugs with me to every race. It was the rare day that I didn’t foul at least half that many. I also always had a book of matches with me. No, not for cigarettes. A matchbook cover was the perfect thickness to clean the points on our old-fashioned ignitions (the striker portion could be used to file off pitting).

THE HODAKA PEOPLE WERE VERY GOOD TO ME, ESPECIALLY CORPORATE EXEC MARV FOSTER, BUT IN MOST CASES WHEN A PART FAILED I WENT LOOKING ELSEWHERE FOR SOLUTIONS.

Not as famous as Jody’s 1974 125 Super Combat, Jody’s last Super Rat 100 didn’t have very many Hodaka parts on it.

Not as famous as Jody’s 1974 125 Super Combat, Jody’s last Super Rat 100 didn’t have very many Hodaka parts on it.

To say that we didn’t trust our bikes in the ‘70s was an understatement. When something broke we went looking for a different part to replace it. In 1973, I was still riding a Hodaka, although I had complemented it with CZs for the big bike classes. The Hodaka people were very good to me, especially corporate exec Marv Foster, but in most cases when a part failed I went looking elsewhere for solutions. My last Hodaka Super Rat used a heavily welded-up Hodaka frame, rear hub and lower-end, but nothing else on my Hodaka-backed race bike came from Hodaka. The forks were prototype Swenco leading links with Curnutt shocks. They replaced the stock 32mm forks; the cylinder and head were from Tracy; the swingarm was from Swenco; the gas tank was the fiberglass one off my CZ, footpegs came from Alex Steel; the seat and front fender came from a Honda, the rear fender from Maico and the front hub was off a Rickman.

A modern mountain bike has a sturdier frame, better brakes and twice as much suspension travel as my 1971 CZ 250. But it doesn’t have the raspy growl of a five-speed Czech two-stroke engine. Oh, by the way, we didn’t waste time with mufflers in the early days. Going deaf was somehow deemed manly.

Fork seals in the ‘70s didn’t seal anything. I used to lift up the fork wipers and stuff foam rubber between the wiper and fork seal to soak up the excess oil.

The concept of steel fenders, paper air filters, welded-on clutch perches, down pipes, round-tube footpegs and ignitions that couldn’t attract a moth on a moonless night may seem neanderthal by today’s standards, but my CZ was the most advanced machine ever made (up to that date). I loved my race bike with a fervent passion—until I got a new one. Then, my love was transferred. Even today, when I’m asked to be a guest at some vintage event glorifying the good old days, I always decline the invitation. Why? I didn’t want to ride my 1974 CZ in 1974 and I sure don’t want to ride it in 2024. A vintage bike to me is the one I just got off of.

WE DIDN’T GIVE A WHIT ABOUT THOSE WHO CAME BEFORE US IN AMERICAN MOTORCYCLING—MOTOCROSS WAS SO NEW THAT NO ONE WAS OLDER THAN US—AND WE WERE ALL 16. WE WERE IN ON THE GROUND FLOOR.

Back in the good old days you ran whatever worked — including a full face screen.

Back in the good old days you ran whatever worked — including a full face screen.

My generation, albeit the first generation of American motocrossers, was lucky because we were part of the original two-stroke crowd. We were young enough to have missed the four-stroke days of scrambles, TTs and hare-and-hounds. No Gold Stars, Manx, Triumphs or Litos for us—we were the new breed of two-stroke riders. It’s strange now to think about all the criticism we took from four-stroke racers about our “rice burners” and “ring-dings.” We reveled in our two-strokes. It was new technology and we were going to use it to change the world. We didn’t give a whit about those who came before us in American motorcycling—we were motocrossers. Motocross was so new that no one was older than us—and we were all teenagers. We were in on the ground floor. In our eyes, the only people better than us were the Euros—they had plied this trade since 1947. We bowed to them, but not to society, flat trackers or enduro riders.

When I first started racing, we raced three motos. I liked that and most of the kids who had come from a dirt track background loved it more. They were used to sitting around all day to race four laps on a quarter-mile flat track. With motocross, they got to ride—a lot. A few years later we switched to two motos. Modern riders have no inkling of why motocross is a multiple-race format. It goes back to the days before production motocross bikes. The racers of the day would take a road-going bike and turn it into a dirt bike. The race wasn’t just about who was the fastest rider on the track, but who was the best mechanic. The multiple motos tested how well prepped the rider’s bike was. The victory didn’t always go to the fastest—it often went to the best prepared. True-to-life races were 45-minutes long. That distance was chosen to test, not only the mettle of the man, but the metal itself. It’s a shame that today’s better physically and mechanically prepared riders only engage in two 30-minute sprints. In the olden days, the race didn’t really start until after the 30-minute mark.

HISTORY IS A RARELY WRITTEN BY THE MEN WHO LIVED IT—INSTEAD IT IS OFTEN OVER-ANALYZED BY THOSE WHO CAME AFTER. THESE ANTE-BELLUM HISTORIANS INFUSE THE PAST WITH NOSTALGIA, QUAINTNESS AND ERRORS.

Jody on his favorite Montesa headed towards the Saddleback finish line.

History is a rarely written by the men who lived it—instead it is often over-analyzed by those who came after. These ante-bellum historians infuse the past with nostalgia, quaintness and errors. They coat it with the colors that they think will make it seem the most romantic or, in some cases, archaic. They make heroes out of the villains, ascribe greatness to machines that were horrid and miss the watershed moments in their hindsight.

I’m here to tell you that there was nothing quaint, cute or nostalgic about the formative days of American motocross. We stood ready, steady and true to the core—we were cutting edge. To modern eyes, motocross circa-1973 may look ancient, but history books aside, you were just as dead if shot down by Manfred von Richthofen in 1917, Richard Ira Bong in 1944 or a Sidewinder missile in 1990. Translation? That means that the fastest of the fast in 1968 was just as fast as the motocross stars of 2024. Hindsight may always be 20/20, but it can never see the hues that colored our time.

I’m not sure that the Red Sox got the short end of the stick in my brief dealings with them. My generation was destined for insurrection. We grew up in a uniform banality that our parents found soothing after the Great Depression of the ‘30s and World War of the ‘40s. We rose to manhood in a black and white world, but craved the color of “Bonanza.” We were nursed on Uncle Miltie, but were kidnapped in our pre-teens by Soupy Sales. Our older siblings were fans of Elvis, but we came of age in Beatlemania. No Cezanne and Matisse for us, we were Peter Max to the max. Our war wasn’t the war to end all wars—it was Vietnam (and “Charlie don’t surf”).

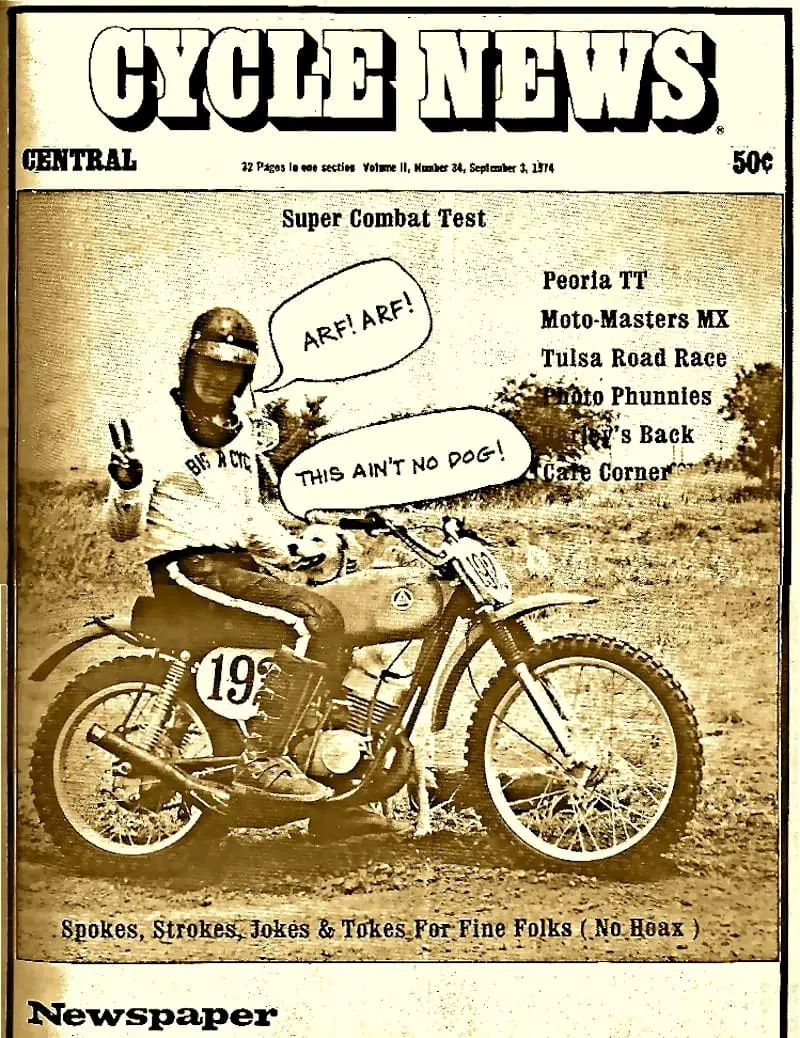

Back in the 1970s you hadn’t lived until you made it to the cover of Cycle News—for Jody and his dog Asia that day came on September 3, 1974.

Motocross, for the men who were in on the ground floor, was a personal statement against the constraints of society. We weren’t in it for the money—there were no million-dollar contracts back then. We weren’t in it for the glory—we raced in a black hole of media blindness. We weren’t in it because it was the cool thing to do—it was, but nobody knew that back then. We weren’t in it to build it into today’s glorious sport of excess and flash—a racer from the ‘70s wouldn’t find modern motocross neither manly or gentlemanly. We weren’t in it because everybody else was doing—we were in it because no one else was doing it.

No! My father was right—motocross wasn’t a sport. It was rebellion.

Comments are closed.