MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE CARMICHAEL’S, HENRY’S & DOWD’S 1998 MX DES NATIONS BIKES

We get misty-eyed sometimes thinking about past motocros bikes we loved, as well as ones that should remain forgotten. We take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and disregarded in the MXA achieves. We reminisce on a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our test of Team USA’s 1998 Motocross des Nations bikes.

Isn’t it strange how the tentacles of misery can reach far beyond their source? As Team USA crated its machinery and headed for England to race the Motocross des Nations, the MXA wrecking crew was standing on the loading dock bidding adieu to Ricky Carmichael’s KX125, John Dowd’s YZ250 and Doug Henry’s YZ400. It wasn’t so much a “goodbye” as “until we meet again,” because as soon as the Motocross des Nations was over, the three machines would be crated up and delivered to the MXA test crew.

It was a brilliant concept (at the time). It was a fairy tale idea (at the time). It was a stroke of genius to line up tests on the bikes that would win the 1998 Motocross des Nations (at the time).

Sadly, Team USA’s defeat at the 1998 MXDN cast a pall over everyone on the American team. When the bikes returned from Europe, they were a bedraggled mess: caked in mud, crusted with British vegetation and, unfortunately, painted with the aura of defeat. No doubt about it, the thrill of riding the bikes of Team USA had diminished. But, as the muddied warriors were spruced up, washed, waxed and readied for their MXA test session, the wrecking crew began to see that these weren’t bikes of defeat but rather of glory. Tested on the muddy fields of Europe, they had survived‚ maybe not conquered‚ but they had definitely not bowed. World domination is not decided by one race in the mud of England any more than it can be claimed from victory in an arenacross. It’s earned by consistency, determination and real-world experience.

STEEDS OF A BLOODY WAR

What makes the bikes of Team USA so unique is that they are unleaded bikes. Under European racing rules, race gas is not allowed. For Team USA to compete against the world, they first have to throw away their American race engines (tuned for a 103-octane cocktail) and tune them to run on pump gas. It’s a daunting task, largely because it takes place in the midst of the AMA National Championships, where manpower is at its leanest, but also because it requires more than just draining the tank and pulling up to the pump.

As each bike was fired up, test riders Gary Jones, Larry Brooks, Jody Weisel, Tim Olson and Willy Musgrave realized that we had been spoiled by our success at the MXDN. Now, after losing four of the last five events, perhaps we will realize that we aren’t defined by our relative position on an imaginary hierarchy. We are the center of the motocross universe. They are the satellites. Hopefully, the misery of our loss will not be forgotten but instead used as an object lesson. Nothing worth having comes easy. We have lost a race in England, but we haven’t lost our pride. These are the bikes of Team USA.

WE RIDE RICKY CARMICHAEL’S TEAM SPLITFIRE KX125

The MXA test crew has ridden Ricky’s bike on many occasions, and each time we have marveled at its tremendous power and minuscule powerband. Carmichael’s powerband of choice is narrow, abrupt, attention getting, hard-to-use and violent. It is neither forgiving nor flexible. You either ride it hard or pay the price. So, as we approached Ricky’s Motocross des Nations machine, each test rider snugged his leathers tighter, pulled on his gloves, put on his race face and prepared to do his best to keep this missile on the pipe.

RICKY’S EURO ROCKET

Surprise! Unlike previous RC machines, his Team USA bike actually had a powerband that didn’t require every ounce of concentration a rider could muster. Thanks to the European unleaded gas regulations, the Pro Circuit-built engine didn’t have as much compression as Ricky’s National and Supercross powerplants. Less compression translates into a less potent hit in the midrange and a considerably longer pull on top. At first, test riders didn’t feel that Ricky’s KX125 was very fast. But that proved to be wrong. In fact, every MXA test rider was faster on the Motocross des Nations bike than he had been on his National bike.

It had a melodic but flat exhaust note (instead of the barking staccato of the last RC bike we rode), and it stayed on the pipe much longer. Test riders still had to hurry it along from gear to gear, but if you flubbed a shift, a slight touch of the clutch would help it climb back into the middle. While it had less bark, its bite was more secure. It grabbed the ground and held on for dear life.

Is it as fast as his AMA National Championship bike? No. On sheer power alone it isn’t, but, with the exception of Ricky Carmichael, few riders in the world could keep his standard-issue light switch on the pipe for more than a few laps. His National bike is faster (for awhile), but his unleaded bike is more consistent. Its speed comes not from a bazooka-like blast, but from the rat-a-tat-tat of a machine gun: repetitive, consistent and in the meat of the curve.

CLASSY KX CHASSIS

Unlike most National Champions’ bikes, Ricky Carmichael’s setup has become relatively friendly: his bars aren’t beyond the norm of local riders; his levers are set in a neutral position; his suspension, while stout, actually absorbs bumps instead of pulverizing them; and his brakes are strong but not touchy.

Of the three Team USA bikes, Carmichael’s KX bristles with the trickest potpourri of parts. It could be because the stock KX125 needs more help, but it’s probably because Pro Circuit leaves nothing to chance. They test each component, try to improve it and then redesign it to beat the new part. Part works bike, part R&D machine and part home brew, Carmichael’s KX125 is the epitome of the modern works bike.

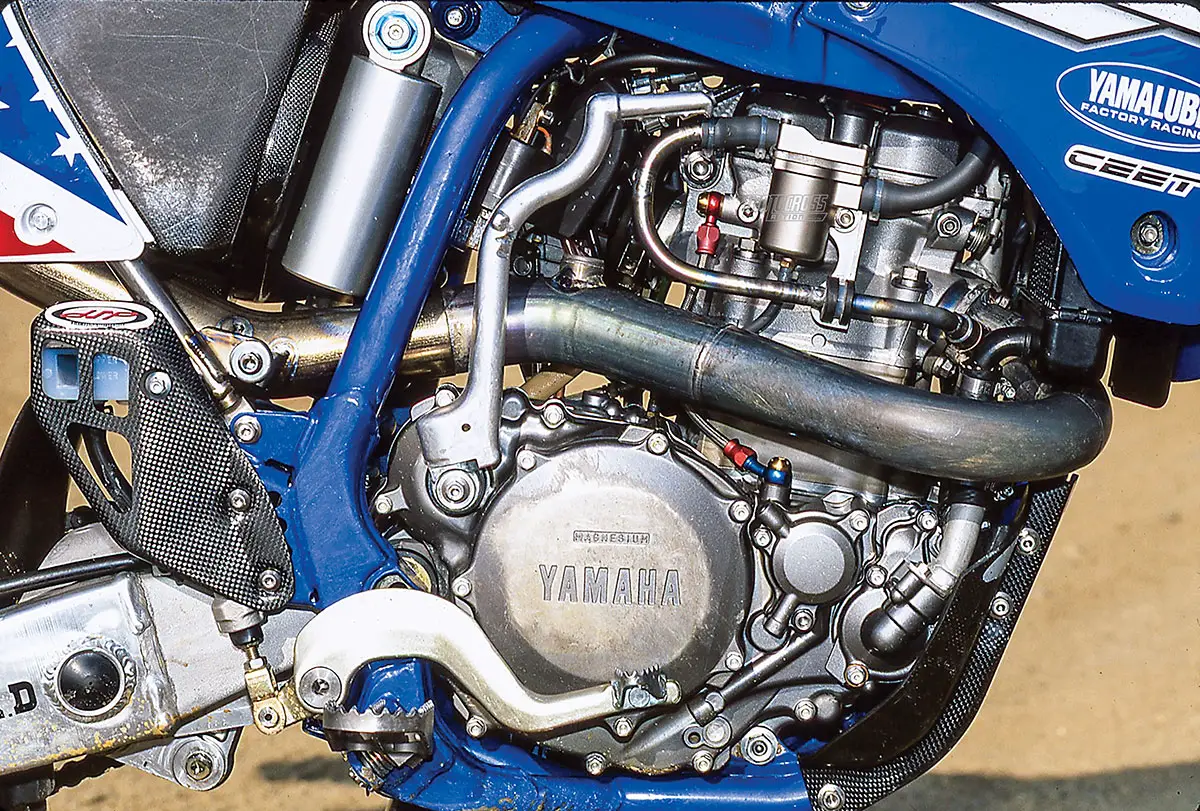

WE RIDE DOUG HENRY’S TEAM YAMAHA YZ400

Allow us to gush! Nothing on earth can prepare you for a spin on Doug Henry’s YZ400. It is a life-changing experience. Forget all you know about four-strokes, because Doug’s bike will make you into a true believer. It rips. Not just on the track, but it rips up all existing concepts of how good a motocross engine can be.

Doug Henry’s Yamaha YZ400 was not affected by the European unleaded rules. Four-strokes, by their very nature, can accept a wide range of fuel changes without being compromised. When the MXA wrecking crew climbed aboard Doug’s YZ400, we were riding his Supercross, National and Motocross des Nations bikes rolled into one.

REINVENTING THE THUMPER

This bike rocks. Throttle response is instantaneous. Compared to a stock YZ400, Henry’s bike is throaty, potent, lively and quick. Whereas the stocker rolls on with authority, Henry’s snaps to attention with dictator-like dominion. Whereas the stocker climbs into a robust midrange, Henry’s surges into a white knuckle rush. Whereas the stocker pulls steadily until the rev limit kicks in (at 11,200 rpm), Henry’s rev limiter never kicks in (it exists but at an rpm setting that we never felt the need to attain). Whereas the stocker is hooked up and hauling, Henry’s flat-out flies.

How good is it? It is the best motocross engine on the planet. There are times when you’d swear it was a two-stroke. On the exit of corners, a quick twist of the wrist delivers a two-stroke-type torrent of power. The factory YZ400 wheelies with ease, while the rapidly rising revs convince you that this is a light-flywheel two-stroke. Then, just as you begin to think it’s too zingy, it smooths out into a tractor and grips the ground the way only a thumper can.

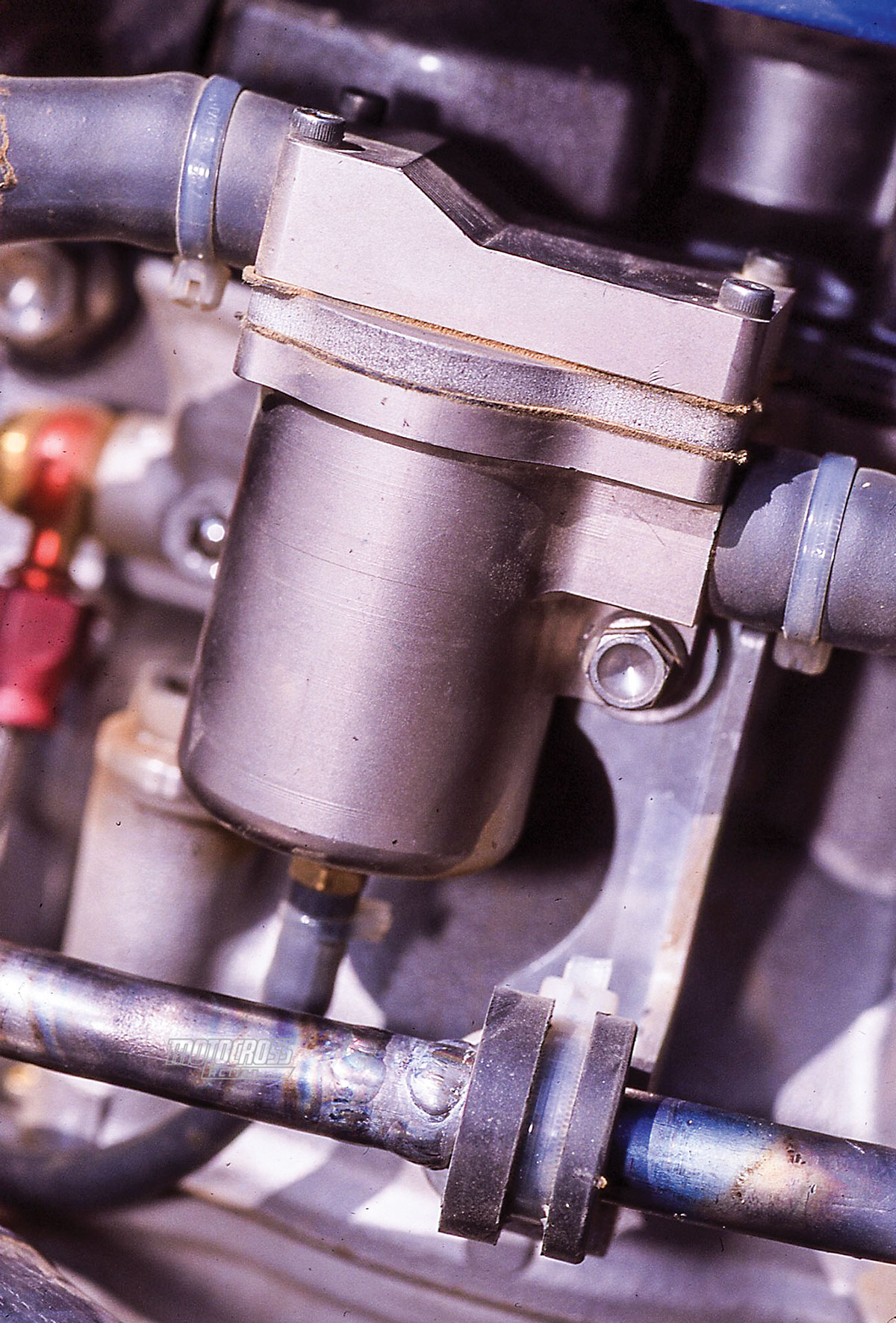

How do they do it? Yamaha engineers take everything out of the YZ400 engine that isn’t absolutely necessary—including the counter balancer. The four-speed gearbox isn’t geared for high speed (but unlimited rev over-rides most gearing shortages). The jetting and ignition are sharp and crisp, yet Doug’s bike starts on the first kick. Horsepower plays a big roll in making Doug Henry’s YZ400 into an awesome weapon. Even though it’s only a four-speed, it will do starts in third gear with ease; but, the spread of power is broader than the stock YZ400’s (and that is broad).

IN HENRY’S IMAGE

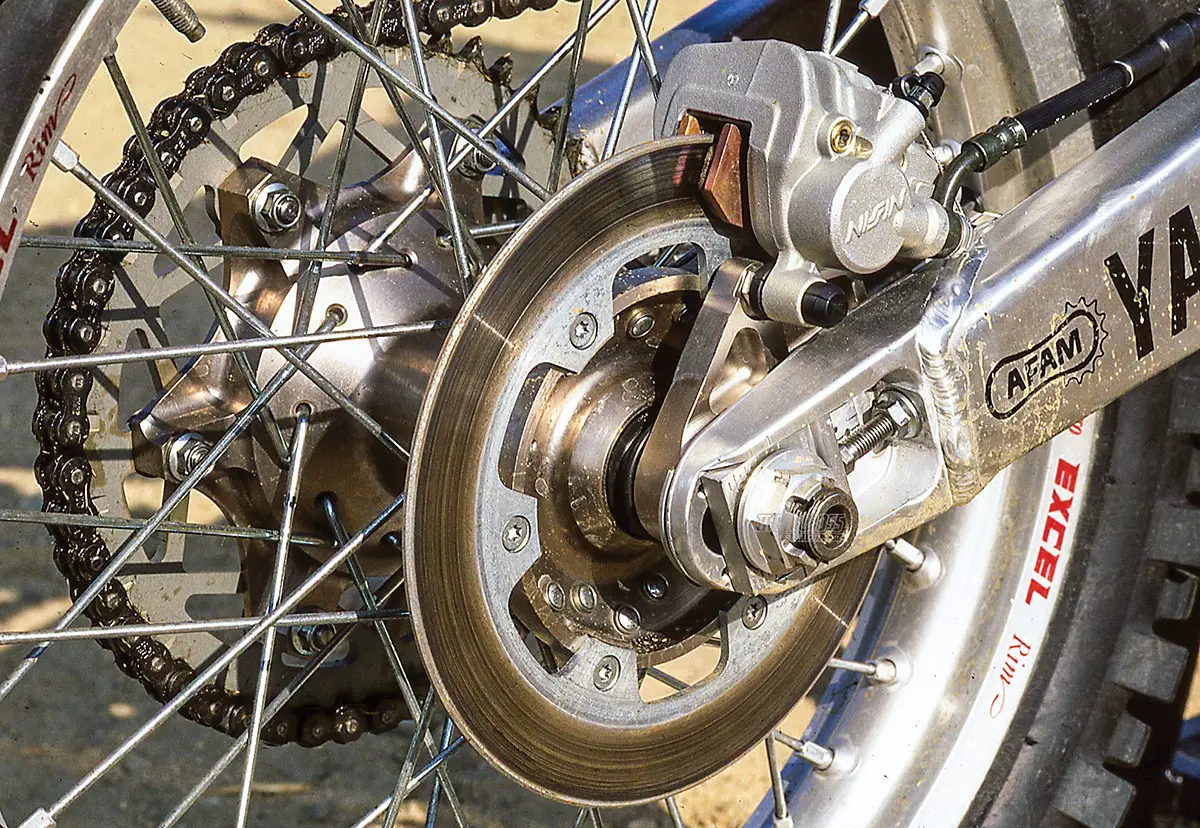

Handling is great (Yamaha’s factory YZ400 weighs under 230 pounds and feels like it), but Doug Henry’s outdoor suspension settings would be a normal man’s Supercross setup. It’s stiff. Sao stiff that you have to ride hard to get the forks to move and even harder to have the rear end follow the ground.

Just as extreme is Doug’s front brake. Very powerful. It’s strong enough to lock the front wheel and cause it to slide on the entrance to turns. Doug runs his rear brake pedal high, which increases leverage on the rear pedal, making the rear stopper prone to easy lock-up. We learned quickly to ride hard and brake softly.

Doug Henry won the first moto at the Motocross des Nations (only to be taken out by the mud in his second moto), but maybe Doug just happened to be on the winning bike. That’s how good this bike is.

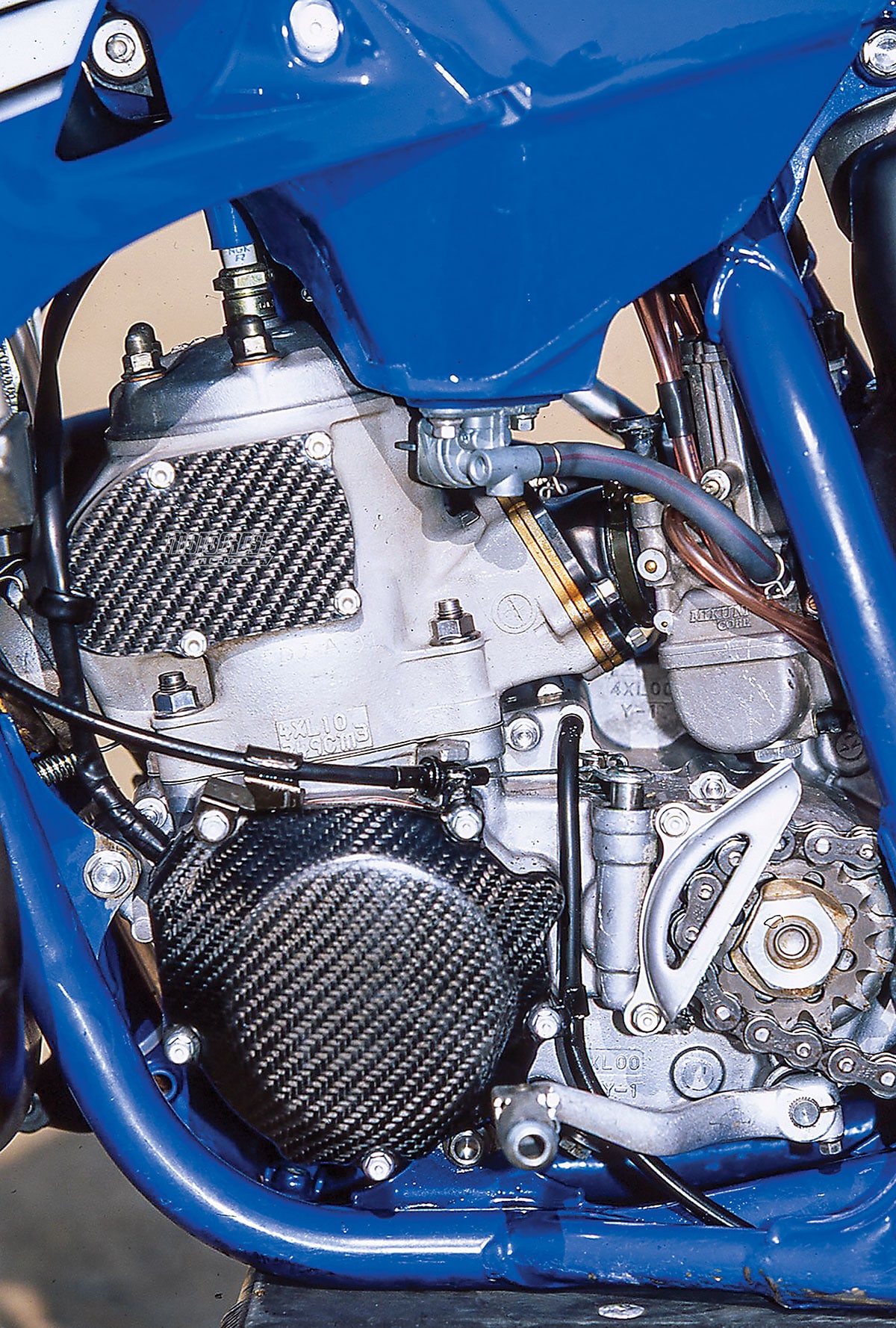

WE RIDE JOHN DOWD’S TEAM YAMAHA YZ250

There was lots of talk in Europe that America didn’t send its best team to the 1998 Motocross des Nations. European pundits pointed to the fact that McGrath, Lusk and Emig weren’t on Team USA (largely because of injuries), but they missed the point. For this event, on this track, in this kind of weather, John Dowd was the best man for the job. Dowd is the American mud master (along with teammate Doug Henry). Dowd, who was drafted out of the 125 class to ride a YZ250 in England, is an established 250 rider of considerable note.

DOWDY’S WEAPON OF CHOICE

Yamaha has not risen to the top of the motocross heap, which is where it is today, by building fire-breathing, arm-stretching, top-fuel dragster powerbands. Yamaha’s ticket to the big-time has been punctuated with broad, easy-to-use and manageable power. That it makes beaucoup ponies, while spreading power across a manageable range, is icing on the cake.

Just like Ricky Carmichael’s KX125, Dowd’s unleaded-prepped YZ250 gave away considerable punch to gain a wide breadth of usable power. Dowd’s Motocross des Nations bike is by no means a rocket-ship. Soft down low, it climbs into the midrange with a steady gush of power. Most test riders found the midrange-and-up powerband to be on the flat side. Yes, Virginia, it pulled across a wide expanse of rpm, but it didn’t do it with that roller-coaster enthusiasm of a works bike. Instead, it droned out its power.

Broad, easy-to-use, and manageable are often euphemisms for slow. Wrong! Dowd’s YZ250 moved with alacrity, but it did it with a metronome-style of power that didn’t register on the adrenaline meter. It was fast without being quick. Able to leap huge chasms without the take-off of an F-18. Swift to the first turn without wheelspin or wheelies.

The workman-like powerband of John Dowd’s Motocross des Nations bike allowed the MXA test riders to go fast by reducing the sensation of speed to less fear-inducing levels.

BACK IN THE SADDLE AGAIN

Dowd and Henry may ride for the same team, race on the same tracks and use the same brand of works suspension, but they don’t adhere to the same philosophy of suspension setup. Dowd’s spring rates, rebound and compression were in the ballpark of mortal man. A wide variety of MXA test riders, who never agree on suspension settings, were of one accord on Dowd’s Kayaba-equipped machine. It worked for everybody.

Team Yamaha’s two Motocross des Nations bikes displayed an amazing dichotomy of motocross development. They were less like brethren than strangers on a train. As exciting as Doug Henry’s bike was to ride, John Dowd’s was mundane. Doug’s YZ400 was a thoroughbred compared to John’s Clydesdale. Both horses have their place in the world, but given our druthers, we’d rather be holding the reins of Silky Sullivan than Old Betsy.

Comments are closed.