MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE DAMON BRADSHAW’S 1990 FACTORY YZ250

We get misty-eyed sometimes thinking about past bikes we loved and those that should remain forgotten. We take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and disregarded in the MXA archives. We reminisce on a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our test of Damon Bradshaw’s 1990 Yamaha YZ250.

“Is there anything you want me to change?” asked Mike Chavez, Damon Bradshaw’s mechanic. “Bars, preload, lever position?” We looked at him as though he was crazy. We had come to ride the bike that Damon had used to win Anaheim, Houston, Pontiac, Charlotte, Los Angeles and Mt. Morris; why would we want to change anything?

“Let me know,” said Chavez, as he poured gas into the 1990 YZ250.

Yamaha had delivered Damon’s bike to the MXA test crew in the exact condition it had been in the last time Damon rode it. Chavez had cleaned it, loaded it up in his box van and met the wrecking crew at Perris Raceway. We were intent on learning everything there was to know about Bradshaw’s factory YZ, and even though Mike offered to set it up for us, we wanted to ride it with all of Damon’s personal touches.

With the exception of the magnesium wheels and works shock, most of Bradshaw’s 1990 Yamaha YZ250 was available from over-the-counter suppliers.

With the exception of the magnesium wheels and works shock, most of Bradshaw’s 1990 Yamaha YZ250 was available from over-the-counter suppliers.

Little did we know that riding Damon’s bike requires some serious changes in attitude—some good and some bad. Every test rider came in from his first warm-up laps with the same comments: “The worst bars on the planet and the broadest powerband in the solar system,” said the astronomers in the bunch.

WE HAD COME TO RIDE THE BIKE THAT DAMON HAD USED TO WIN ANAHEIM, HOUSTON, PONTIAC, CHARLOTTE, LOS ANGELES AND MT. MORRIS; WHY WOULD WE WANT TO CHANGE ANYTHING?

Damon’s personal bar bend was the subject of a lot of complaints. It’s hard to imagine that a rider as fast as Damon could have selected such an old-fashioned bar bend. Damon’s Answer Alumilite bars are very tall, with the bar ends swept back and up. The bar bend cramps the wrists by turning them outward and upward. Indisputably, Damon’s bars are the strangest on the National circuit.

Equally indisputable is the incredible spread of power the Yamaha factory was able to get out of Damon’s YZ250 engine. To tell the truth, the MXA test crew had expected the factory Yamaha to have a hard midrange powerband that enhanced the explosive and quick nature of the stock YZ engine. By no means were we expecting smoothness, tractability and a top-end rev that could make dogs howl three miles away. Damon’s engine was awesome and powerful but manageable.

Back in the 1990s, footpegs were narrow. Yamaha simply welded an extra cage on the back of Damon’s pegs to widen them.

Back in the 1990s, footpegs were narrow. Yamaha simply welded an extra cage on the back of Damon’s pegs to widen them.

“WHERE’S THE EXPLOSION? HOW COME IT’S NOT SHREDDING A TRENCH 6 INCHES WIDE?” YOU WONDER AS YOU GRAB THIRD GEAR. “WHY ISN’T…” AND BEFORE YOU CAN FINISH, THE FRONT WHEEL HAS STARTED TO CLIMB TOWARDS THE SKY.

Tuner Bud Aksland spec’d out the cylinder porting for Team Yamaha, while Bob Oliver did the porting at the Yamaha race shop. A Bill’s Pipe is mated to a Pro Circuit silencer to provide the final exhaust touches. We snooped as deeply as possible into the YZ250 engine, looking for works parts left over from the old days or some super-secret gizmos, but there weren’t any. The carb was a stock 38mm Mikuni. We did notice that the float-bowl drain nut had been milled down. Chavez told us that Yamaha milled the nut to keep it from vibrating against the cases. The reeds were stock units with the stops set at standard height. The plug was an NGK B8EV, and the gearing was 14/49. Chavez said that occasionally Damon would opt for a 50-tooth rear sprocket.

The ignition was different, but it wasn’t unobtainable. A 1989 YZ250 ignition was used on Damon’s bike, and Chavez said that different-size rotors were used to match track conditions. A check of the gas tank revealed VP C-12 racing fuel with Yamalube-R oil mixed at 35:1.

The workmanship and hop-ups were thorough, but nothing hinted at the performance that lurked inside Damon’s YZ250 engine.

As you snick the bike into first gear and blip the throttle on your way to the starting line, you don’t feel anything special. It doesn’t jump out of your hands or jerk your elbows to full lock. It just motors along and even feels a tad sluggish at that. Behind the starting gate, you select second gear and, because this bike has won races all around the world, you decide to give it everything you’ve got (no use plunking around on a factory bike). When the gate drops, you launch over the gate with a healthy handful. It goes, but you’re disappointed. “Where’s the explosion? How come it’s not shredding a trench 6 inches wide?” you wonder as you grab third gear. “Why isn’t…” and before you can finish, the front wheel has started to climb towards the sky. It’s wagging there, waiting for you to loop out or go for it. You shift to fourth and your eyes start to water. Fence posts are blurring by on your left. “No more,” you scream inside your helmet and shut down the throttle.

The lugs at the bottom of Damon’s forks were hand-milled out of magnesium with a brake that allowed the YZ250 to use a larger front disc. The urethane bumper acted to lessen the effects of bottoming.

The lugs at the bottom of Damon’s forks were hand-milled out of magnesium with a brake that allowed the YZ250 to use a larger front disc. The urethane bumper acted to lessen the effects of bottoming.

COOLING OUR HEELS

Around the first turn, you take a quick breather. You probably just leaned back too much, but for the next couple of corners, you cool it with the throttle. “Funny,” you think to yourself, “it doesn’t feel incredibly powerful.” There is no burst of power, no uncontrollable surge and no explanation for how such a mellow-feeling engine had gotten you to the first turn in such a frenzy. After cruising for the first half lap, you decide to unwind Damon’s YZ and air it out on the back straight. Coming out of the berm, the YZ250 has a very controllable feel. The bottom-end power is predictable and controllable but not works-like. As you crank the bars and twist your wrist out of the berm, the engine begins to accelerate. You come out of the berm in second gear, and you have your foot under the shift lever ready to make that tricky YZ upshift to third. Coming into the midrange, Damon’s bike begins to lift the front wheel and climb into a powerful midrange. Your foot is waiting to shift. The front wheel stays a foot off the ground as you begin to hit the top end. You’re still waiting to shift when you reach the end of the straight.

“It can’t be true,” you say to yourself. “I just did a third-gear straight in second gear. I must really be dogging it.” Out of the next turn, you rap the YZ on, and the same thing happens again. The power builds steadily, geometrically and endlessly. It goes and goes—only on this straight you shift to third gear, not because the YZ needed to be shifted, but because you felt like a major flog riding around the track in second gear. Heck, go for fourth; after all, the rest of the wrecking crew is watching. It pulls tall gears, revs out low gears and does it all with a beautifully controllable crescendo of power.

All of this power is emanating from a 1990 YZ250 engine. With the exception of porting, pipe and ignition mods, it is almost stock.

Magnesium triple clamps.

Magnesium triple clamps.

YAMAHA DOES HAVE TRICKS

The power is the most impressive part of Damon’s bike, and the bars are the most depressing thing, but there is a lot of trickery hiding behind the plain-looking YZ.

The axles, shock linkage, pivot bolts and swingarm bolt are all titanium. Ultra-light magnesium wheels are laced to red-label Excel rims with aluminum spoke nipples in the front and brass nipples in the rear. Most of the non-stressed bolts are aluminum bolts from Pollipolini in Italy, while the remainder are titanium.

Damon, like all factory riders, runs wider footpegs than stock. He uses Scott MX-2 grips with Scott grip tape on the brake and clutch levers. A stock YZ250 throttle is used.

For sand tracks, Damon normally runs a Dunlop 752 on the rear, but for most track conditions he chooses either a Dunlop K695 or the (unavailable) 704.

Inside the tranny, the factory mechanics have a few tricks to improve shifting. First, they polish the shift drum to lessen stiction. Second, they mill out the cases at the shift shaft and install a bearing to allow the shifter to move unhindered. Third, Damon uses Maxima transmission oil. Finally, the clutch is equipped with works clutch plates, and both the aluminum and fiber plates are of higher quality but not different in dimensions or width. The clutch springs are stock.

Damon likes his saddle to be firm. Mechanic Mike Chavez replaces the stock seat with a new one (with Damon’s personalized seat cover) every two races. For stopping power, Damon uses a stock rear brake setup with Motul 300c brake fluid and accessory brake pads for longer life. The front brake has a bigger rotor (with the caliper hanger machined to accept it), a plastic brake line and a stock master cylinder.

The air filter is a Uni filter. Mike Chavez zip-ties the airbox to the frame to keep it from bouncing around in stadium whoops.

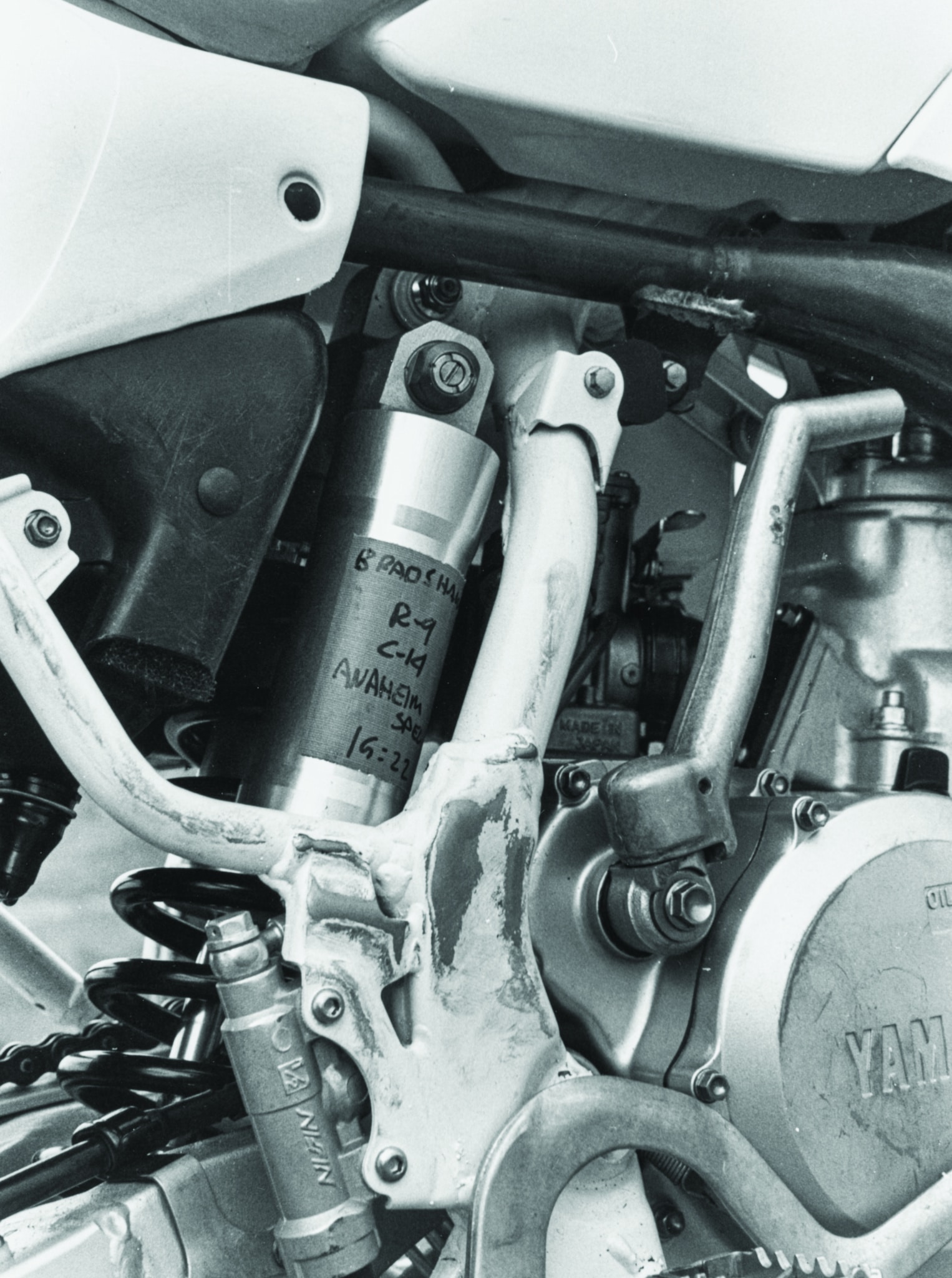

Kayaba supplied Damon’s YZ250 with a billet-aluminum shock.

Kayaba supplied Damon’s YZ250 with a billet-aluminum shock.

A CLOSE LOOK AT THE SUSPENSION

Damon sets up his suspension a bit differently from most of the works bikes we have ridden; however, the front forks aren’t that different. The 43mm Kayaba works forks use a magnesium casting for the axle clamps, aluminum stanchion tubes, magnesium triple clamps, an oversized aluminum steerer tube, stiffer fork springs and a special urethane bottom-out bumper in the fork legs.

In action, the forks were very solid, well-damped and firmly sprung. Although not as responsive to small bumps as they could be, Damon’s works forks absorbed everything bigger than a whoop like it was upholstered in silk. The faster you went, the better the forks worked. Big jumps, which most local racers allow their bikes to bottom on, didn’t get all the way through the works Kayaba’s travel range. Bradshaw’s fork setup mimicked most factory riders’ desire for forks stiff enough to handle quasar jumps—the heck with the little stuff.

In the back, we were shocked to find a very supple rear shock. Yamaha uses the stock 1990 linkage connected to an aluminum-bodied Kayaba works shock. It was equipped with a stiffer spring, but basically it was a soft, absorbent and pliable rear end, perhaps the softest rear shock we had ever felt on a works bike and a major contrast to the stiff front forks. It’s no secret that guys who win Supercrosses and Nationals go faster than mere mortals, thus they hit bumps at higher rates of speed, jump farther, land harder and generally need stiff suspension to handle their acrobatics. Damon had a stiff front end on his YZ but used rear suspension that would work perfectly for the average guy, regardless of his speed.

DAMON GOT A NEW 1991 YAMAHA YZ250 THE DAY AFTER WE RODE HIS BIKE, AND THE BIKE HE RODE TO SO MANY VICTORIES IN 1990 WAS RELEGATED TO THE PARTS BINS BACK AT THE FACTORY WORKSHOP.

We wore out Damon’s factory YZ250. We started riding in the morning and kept going until the sunset. Most factory bikes are pampered during the racing season. They are only used for Nationals and Supercrosses and some limited testing. If Damon wants to go out and practice during the week, he rides a practice bike. The number of hours on a factory bike in a season is amazingly small, and even then, it gets new parts to eliminate the possibility of failure. There’s no doubt that our eight hours of trashing Damon’s bike shortened its life by a considerable amount. Don’t worry, though; Damon got a new 1991 Yamaha YZ250 the day after we rode his bike, and the bike he rode to so many victories in 1990 was relegated to the parts bins back at the factory workshop.

TECHNICAL SHEET INSIDE DAMON’S YZ250

ENGINE

Porting: Bud Aksland

Pipe: Bill’s Pipes

Silencer: Pro Circuit

Carburetor: Stock YZ

Reeds: Stock YZ

Plug: NGK B8EV

SUSPENSION

Forks: 43mm Kayaba aluminum tubes

Triple clamps: Magnesium

Shock: Works Kayaba

Linkage: Stock YZ

Axles: Titanium

CHASSIS

Frame: Stock YZ

Hubs: Magnesium

Tires: Dunlop K490/695

Rims: Excel

Air filter: Uni

Weight: 218 lb.

Comments are closed.