THE REAL STORY OF AMERICA’S MOST FAMOUS DIRT BIKE DESIGNER: HORST LEITNER

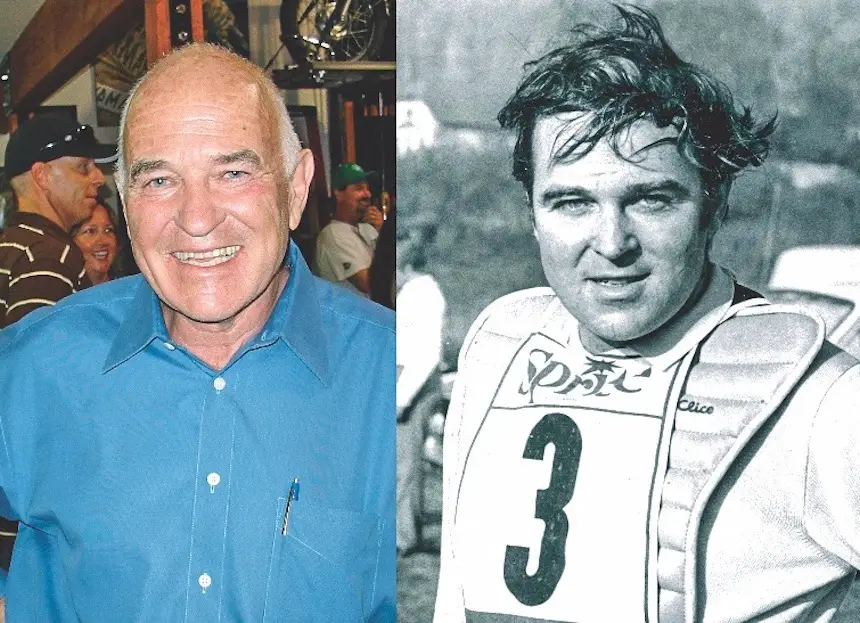

Horst Leitner was a Grand Prix motocross racer and ISDT Gold Medalist in the 1960s. He emigrated to the USA in the 1980s.

Horst Leitner was a Grand Prix motocross racer and ISDT Gold Medalist in the 1960s. He emigrated to the USA in the 1980s.

BY JODY WEISEL

In the annals of American motocross, only one man can lay claim to having played the primary role in the development of a series of important offroad motorcycles, designed bikes for major corporations and foreshadowed America’s interest in four-stroke motocross bikes. That man is Horst Leitner. Born in 1942 near Salzburg, Austria, Leitner was a Grand Prix and ISDT motorcycle racer. He earned four ISDT gold medals in the demanding International Six Days Trials, along with the Austrian National Motocross Championship. But, Horst Leitner saw America as the place where his motorcycling dreams could come true. Thus, Horst loaded up his family and moved from his home country to the United States in 1980. Living in a motorhome, Horst bet everything on his engineering background and creative mind.

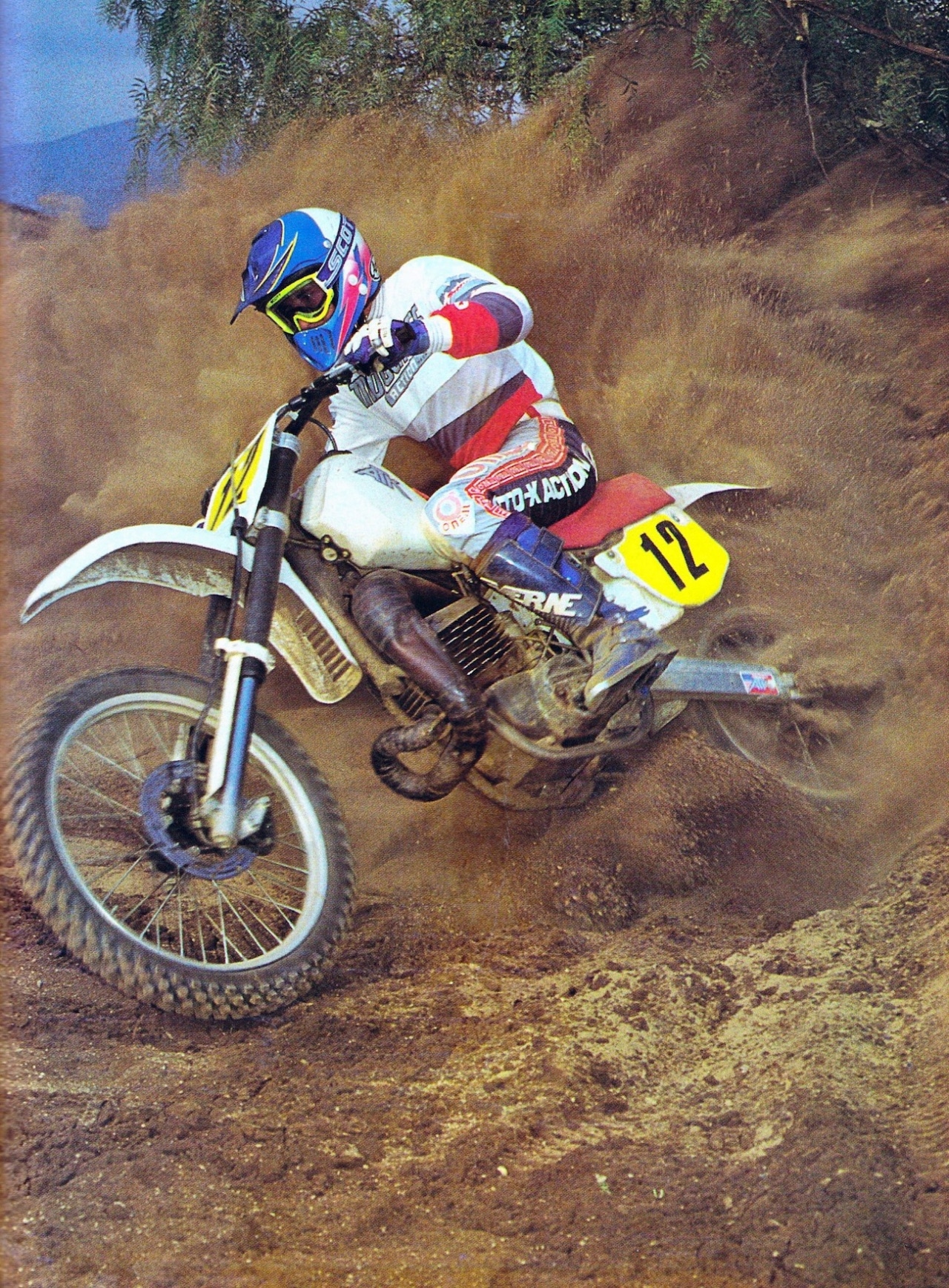

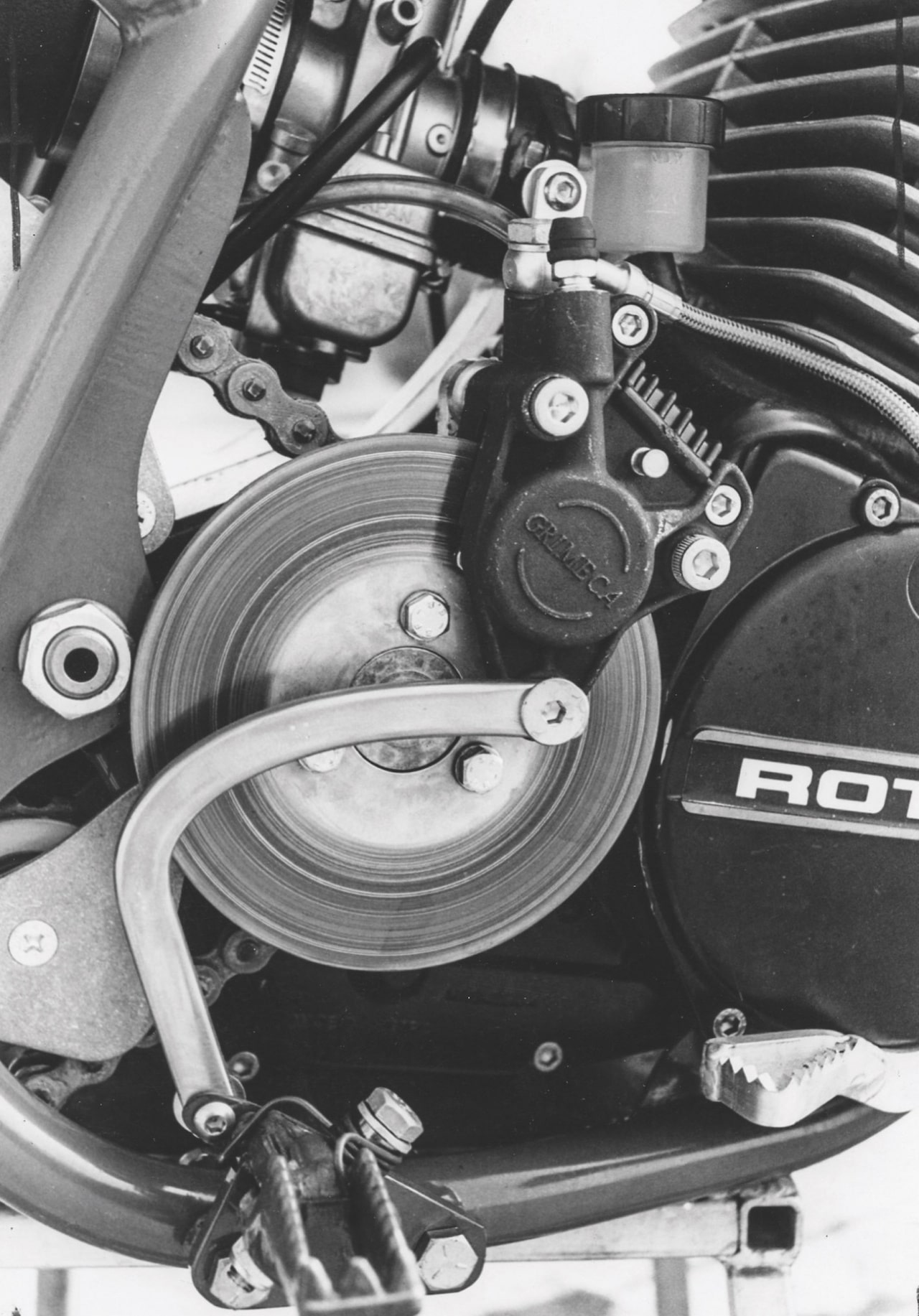

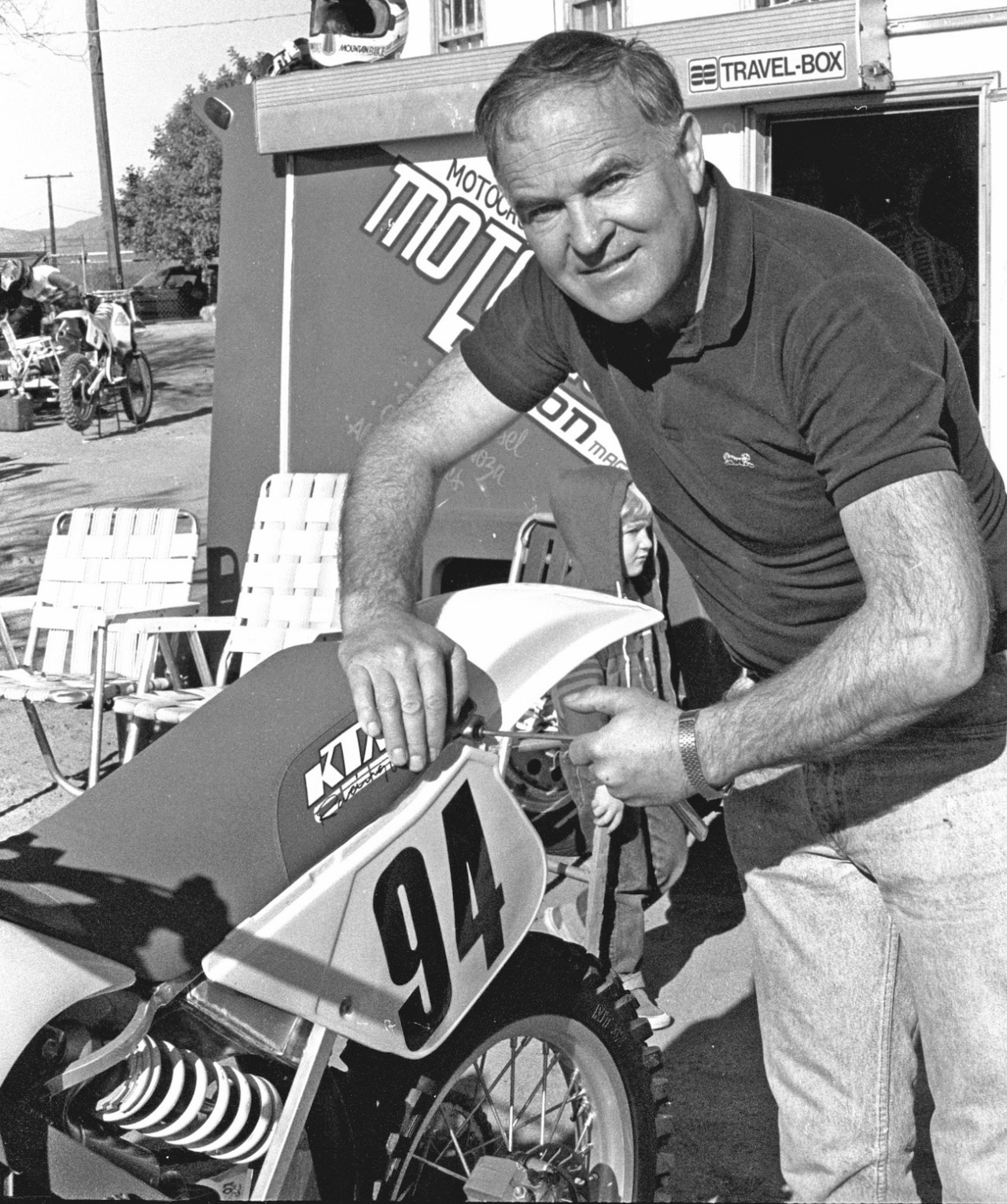

Originally, ATK specialized in four-strokes only. People kept asking for two-strokes, so Horst tucked a Rotax 406cc engine in a four-stroke frame. This photo was shot on day one of testing in 1987.

Originally, ATK specialized in four-strokes only. People kept asking for two-strokes, so Horst tucked a Rotax 406cc engine in a four-stroke frame. This photo was shot on day one of testing in 1987.

HORST LEITNER’S GOAL WAS TO “BUILD A MOTORCYCLE THAT WAS CHEAPER TO MANUFACTURE, 10 POUNDS LIGHTER, BETTER HANDLING, EASIER TO WORK ON, INCREDIBLY NARROW AND ADVANCED ENOUGH TO STAY CONTEMPORARY FOR A DECADE OR MORE.”

Horst was an engineer, and his first inclination was to turn his innovative ideas on chain torque into a series of products for both street and dirt motorcycles. Next, he designed and built motocross frames that would accept Honda XR350 engines; in essence, Rickman Metisse-style kits for the 1980s Honda four-stroke engines. The success of his frame kits attracted a member of the Puch family, who approached Horst with the idea of producing a new motorcycle brand. The Puch name was well known in the motorcycle manufacturing business, as the Austrian-based company had won the 1975 FIM 250 World Championships with its limited-production twin-carb Puch MC250.

Leitner jumped at the idea when the Puch heir promised to secure Horst everything required to build a motorcycle, including access to Rotax four-stroke engines. This was the impetus that Horst needed to design and build his own motorcycle brand—ATK. The ATK 560 and ATK 604/605 four-strokes were instant hits. Every ATK 605 buyer was committed to the idea that the four-stroke was the powerplant of the future — a decade before the YZ400F was introduced.

Back in 1989 nothing was as intimidating as an ATK 604E (electric start) four-stroke bearing down on you from behind. It sounded angry. The motocross world was all two-strokes back then, so four-strokes were looked on then as two-strokes are now.

Back in 1989 nothing was as intimidating as an ATK 604E (electric start) four-stroke bearing down on you from behind. It sounded angry. The motocross world was all two-strokes back then, so four-strokes were looked on then as two-strokes are now.

Horst sold thousands of ATK 560 and 605 thumpers (with price tags ranging from $7000 to $10,000). Owning an ATK was like owning a Mercedes-Benz; it was a status symbol. His thumpers were so successful that when Team Honda mounted an assault on the 1984 World Four-Stroke Championships, they built Ron Lechien and Johnny O’Mara Honda-powered ATK copies.

HORST SOLD THOUSANDS OF ATK 560 AND 605 THUMPERS (WITH PRICE TAGS RANGING FROM $7000 TO $10,000). OWNING AN ATK WAS LIKE OWNING A MERCEDES-BENZ; IT WAS A STATUS SYMBOL.

When approached by the Bombardier Corporation in 1988 to build a prototype two-stroke to replace its aging fleet of Can-Am offroad bikes (after a brief partnership with the British Armstrong firm had failed), Horst built one of the most unique offroad motorcycles of all time—the ATK 406 two-stroke. This was destined to become the new Can-Am, as the Bombardier factory didn’t want to run a motorcycle assembly line in Canada anymore.

The ATK 406 was financed by Can-Am dealers in 1987. The first ATK 406 two-stroke rolled off the assembly line on November 1, 1987 (six years after the first ATK four-stroke debuted).

The ATK 406 was financed by Can-Am dealers in 1987. The first ATK 406 two-stroke rolled off the assembly line on November 1, 1987 (six years after the first ATK four-stroke debuted).

Horst had a small cottage factory in Laguna Beach, California, that was capable of producing enough bikes to supply the Can-Am network — as long as Can-Am/Bombardier underwrote the operation. The only requirement was that Horst’s Can-Am prototype had to use the antiquated, air-cooled, 250cc and 406cc, two-stroke Rotax engines. Rotax was owned by Bombardier who saw a chance to get rid of old stock engines. Knowing that the engine was a liability, Horst set out to design a bike so light, simple and unique that no one would notice the engine.

You never knew where to look first on a ATK. In this view, you can see the airbox. It is mounted in the gas tank (right behind the triple clamp).

You never knew where to look first on a ATK. In this view, you can see the airbox. It is mounted in the gas tank (right behind the triple clamp).

Horst’s ATK 406 had a backwards-facing brake pedal (so that it couldn’t be bent in a crash), countershaft rear brake (to lessen unsprung weight on the rear wheel), single-sided/no-link rear suspension (to save 6 pounds over a linkage bike), an anti-chain torque device (to allow the suspension to move freely under drive), and the airbox was in the gas tank (fed by a snorkel that increased horsepower on the aged Rotax engine).

The coolest trivia about ATK is that only one man knows what the initials ATK stand for, but we are about to tell you the secret. ATK stands for Anti-Tension Kettenantrieb, which in English translates to Anti-Chain Tension (which would have made it the ACT 406).

FOR A DESIGNER, MAKING PRODUCTION MOTORCYCLES IS THE KISS OF DEATH. HORST DIDN’T WANT TO MAKE 1000 COPIES OF ONE DESIGN; HE WANTED TO MAKE 1000 DESIGNS WITH ONLY ONE COPY OF EACH.

Horst Leitner’s designs bristled with innovations. This ATK 250/406 has a side-mounted gas cap, backwards facing brake pedal, anti-chain torque driveline and the rear brake mounted on the countershaft sprocket.

Then it all came crashing down. Can-Am canceled the deal with Horst after the prototypes were already built and elected to get out of the motorcycle business completely. Can-Am’s dealers, aware of the prototype and without a product for their showroom floors, pressured Horst to put the ATK 406 into production. He agreed, but only if the dealers paid for the machines up front. They did!

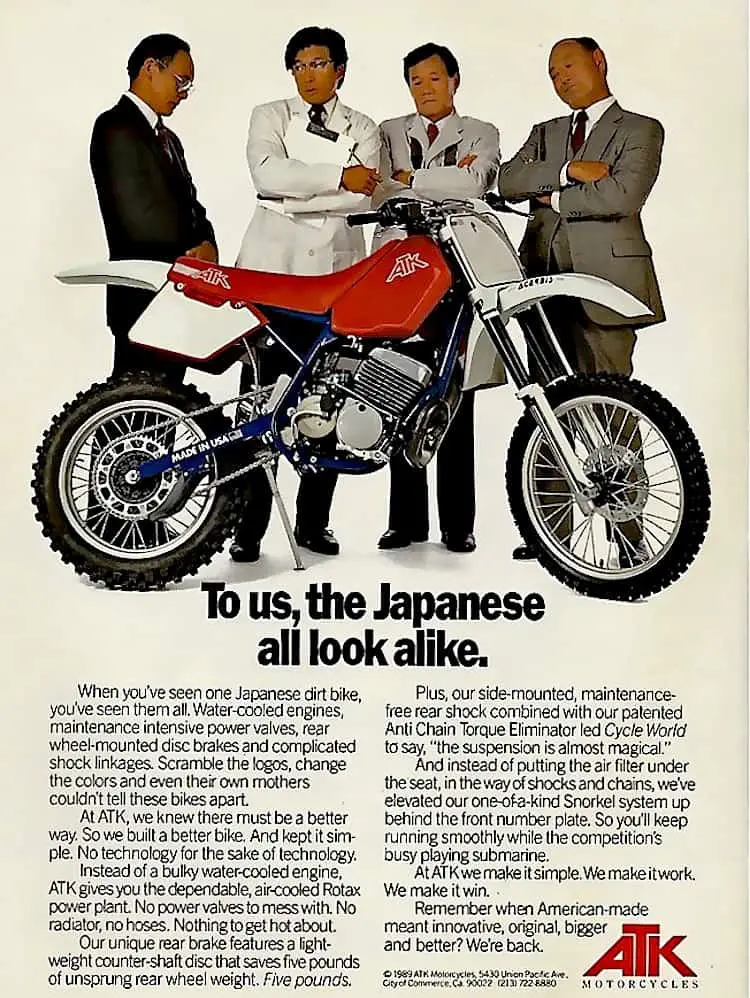

ATK’s advertising was controversial, to say the least.

For a seven-year period (1989–1995), the combined ATK 605 four-stroke and ATK 406 two-stroke sales made ATK the fifth largest offroad motorcycle company in America. The bike would stay in production for ten years and be produced in the thousands from Horst’s small Laguna Beach, California, workshop (and later from a factory in Commerce, California). If Can-Am’s dealer network had not elected to finance the production of the ATK 406 as a replacement to save their dealerships, ATK would never had the economy of scale to grow as big as it did.

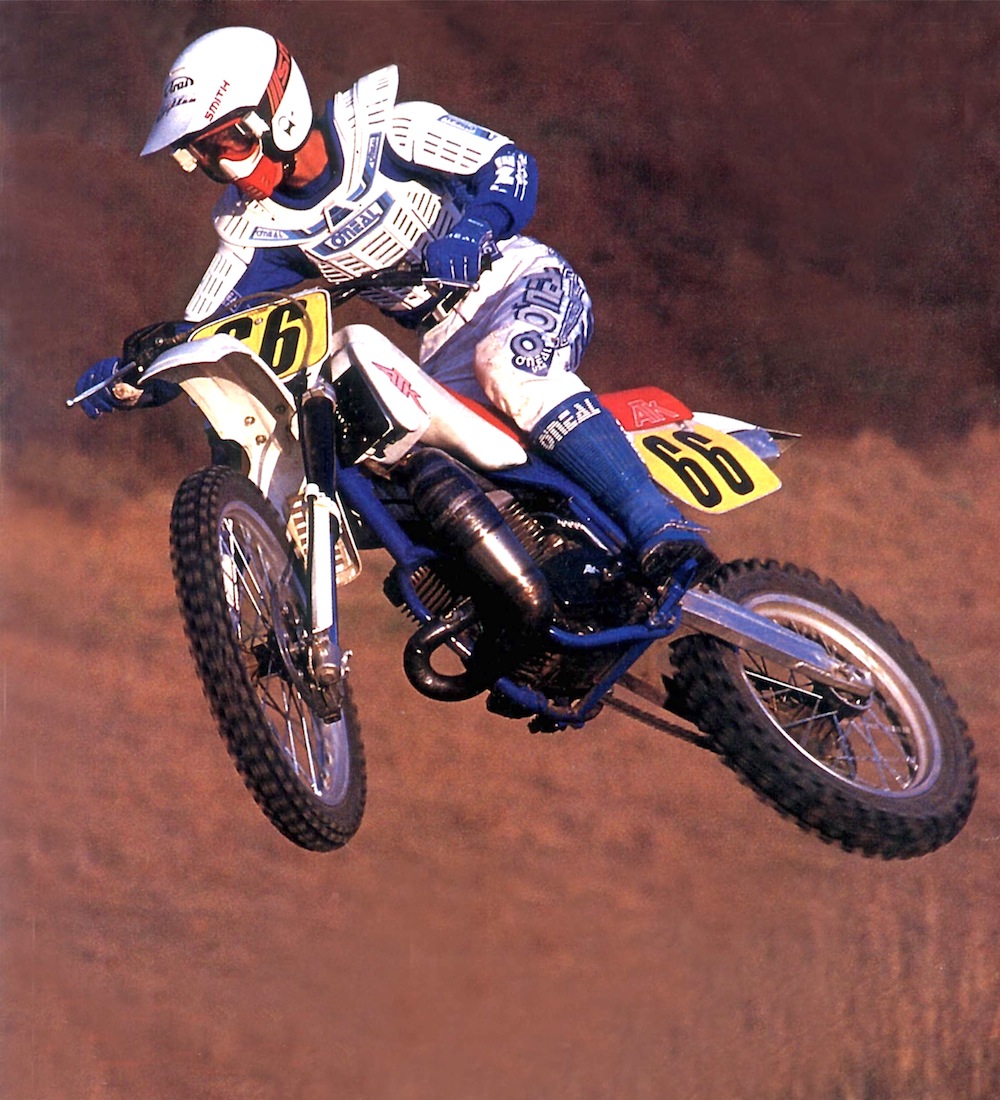

ATK 406 Rotax-powered two-stroke.

ATK 406 Rotax-powered two-stroke.

For a designer, making production motorcycles is the kiss of death. Horst didn’t want to make 1000 copies of one design; he wanted to make 1000 designs with only one copy of each. So, he sold ATK Motorcycles to a conglomerate that moved it to Utah.

As an engineer Horst Leitner couldn’t stop inventing. This was his linkage front fork on a Honda CR500.

As for Horst, he changed the name of his company to AMP Research and began taking on engineering projects. He worked on braking and transmission techniques for Polaris snowmobiles. He designed a military bike for Harley-Davidson. He designed an EZ-Pull clutch mechanism that not only made Harley clutches easier to pull but increased the braking power of electric-powered cars.

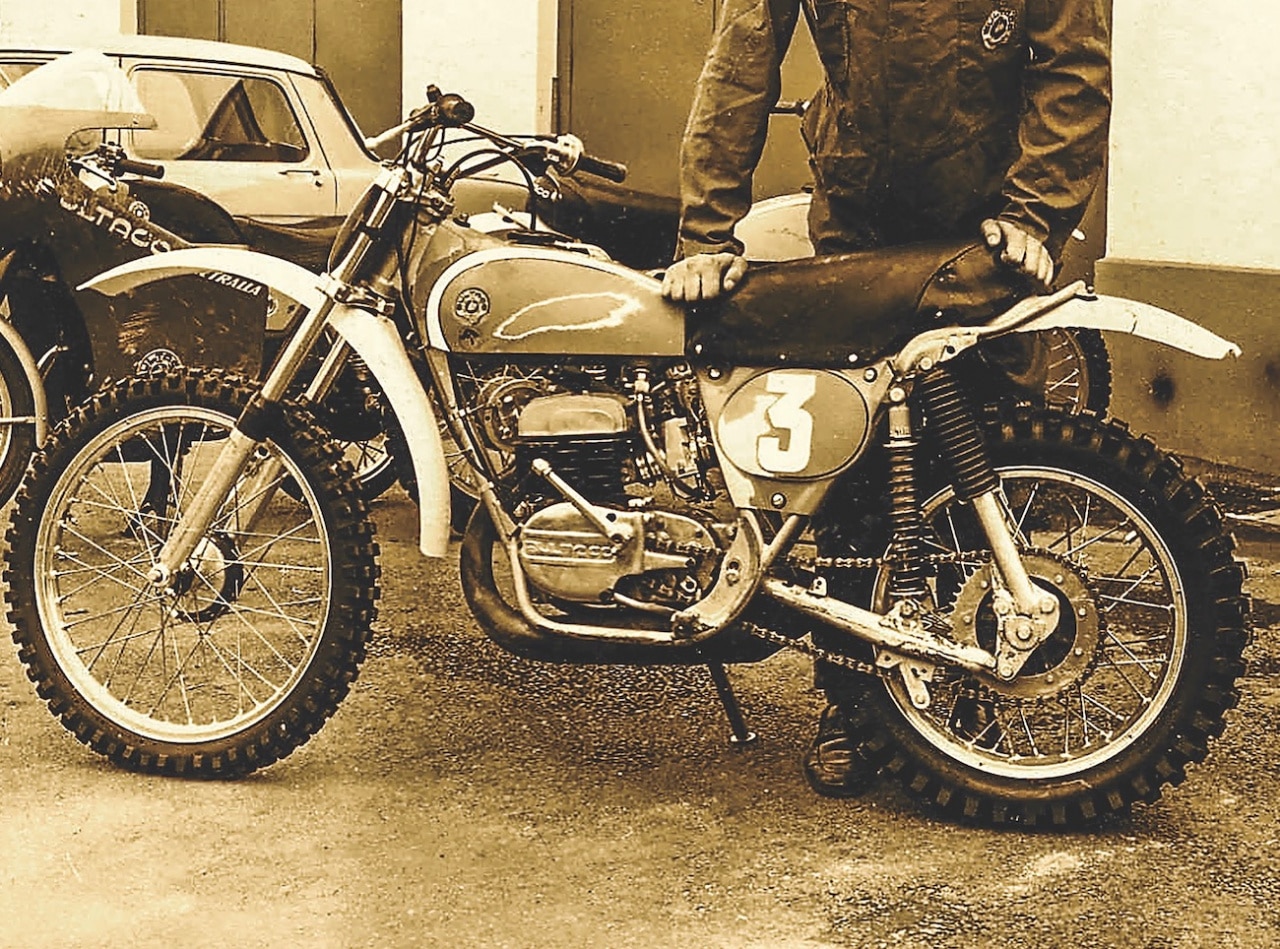

While Horst Leitner was racing the Austrian Nationals, he built a prototype Bultaco that used what would become decades later the basis of his Mountain Bike Hall of Fame FSR suspension system—known as the Horst link. It’s unique

When he turned his attention to mountain bikes, he was in his element. He built prototype rear suspension designs that rocked the foundation of the primitive rear-suspension market. His Horst Link suspension design was snapped up by Specialized, and versions of it are still in production today. Furthermore, he pioneered the use of disc brakes on mountain bikes with a diminutive brake that compensated for pressure gain.

Surprisingly enough, Horst Leitner has been ignored by the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame, but for his efforts in advancing mountain bike technology, Horst Leitner was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in 2015.

Built under commission from KTM as the “125 of the future,” Horst’s 1990 AMP Research 125 weighed under 190 pounds thanks to its minimalistic chromoly parallax frame design

Perhaps Horst’s best-known engineering project began at the 1989 Milan Motorcycle show in Italy. Horst Leitner had flown from Laguna Beach to meet with the new corporate managers of KTM. The Austrian motorcycle firm had been taken over by a large holding company, and the new owners were looking for ways to improve the stodgy, almost nonexistent, American image of their new venture. Leitner, an expatriate Austrian, had built a reputation as the most successful freelance motorcycle designer in the world. His Laguna Beach-based AMP Research firm had turned out design concepts, ideas and complete motorcycles for a wide range of uses.

To lessen unsprung weight on the suspension, Horst moved the rear brake on his ATKs onto the countershaft—and turned the brake pedal around so that it faced backwards.

To lessen unsprung weight on the suspension, Horst moved the rear brake on his ATKs onto the countershaft—and turned the brake pedal around so that it faced backwards.

Given that Horst Leitner was a former Grand Prix motocross racer, ISDT gold-medal winner, owner of a casting company that did business with other European motorcycle manufacturers and was part of a family of racers who were also the Suzuki car importers in Austria, he was the best choice for KTM’s new bosses to approach with an offer. He was an outsider who was an insider. So, in Milan, KTM’s owners (Git Trust) asked AMP Research to build them a prototype of the 125 two-stroke of the future. The carrot at the end of the stick wasn’t the money that KTM agreed to pay Horst for the one-off machine, but the chance to design future KTM models.

Before the AMP Research 125 KTM project was started, Horst built a full-size mock-up—that included most of the strategic points and cardboard radiator wings.

Why was KTM’s management going outside of their own corporation to hire an independent motorcycle designer? After all, they had a bevy of designers and engineers in their employ in Mattighofen. The new investors suspected that KTM’s in-house design staff had failed to deliver stellar products in the past and didn’t want to trust their sizable investment in the company to the same men who had failed to deliver for the old owners. They wanted to bring in a Pro from Dover. They chose Horst Leitner as a way of showing the existing KTM designers that their jobs weren’t safe. The new owners reasoned that outside competition would wake up the Austrian design team. The decision to ask Horst Leitner to design a totally new bike had more to do with bureaucratic politics than a search for creativity.

The AMP Research frame used three chromoly tubes (two rectangular and one round) to comprise 95% of the frame.

The AMP Research frame used three chromoly tubes (two rectangular and one round) to comprise 95% of the frame.

Horst stated that his goal was to “build a motorcycle that was cheaper to manufacture, 10 pounds lighter, better handling, easier to work on, incredibly narrow and advanced enough to stay contemporary for a decade or more.” KTM told Horst that he had to use as many existing KTM components as possible, and that included the forks, wheels, swingarm, brakes, ignition and complete KTM 125 two-stroke engine. These were nonnegotiable parts, but everything else was fair game. And, Horst played fast and loose with the rules as laid out.

KTM TOLD HORST THAT HE HAD TO USE AS MANY EXISTING KTM COMPONENTS AS POSSIBLE, BUT EVERYTHING ELSE WAS FAIR GAME. AND, HORST PLAYED FAST AND LOOSE WITH THE RULES AS LAID OUT.

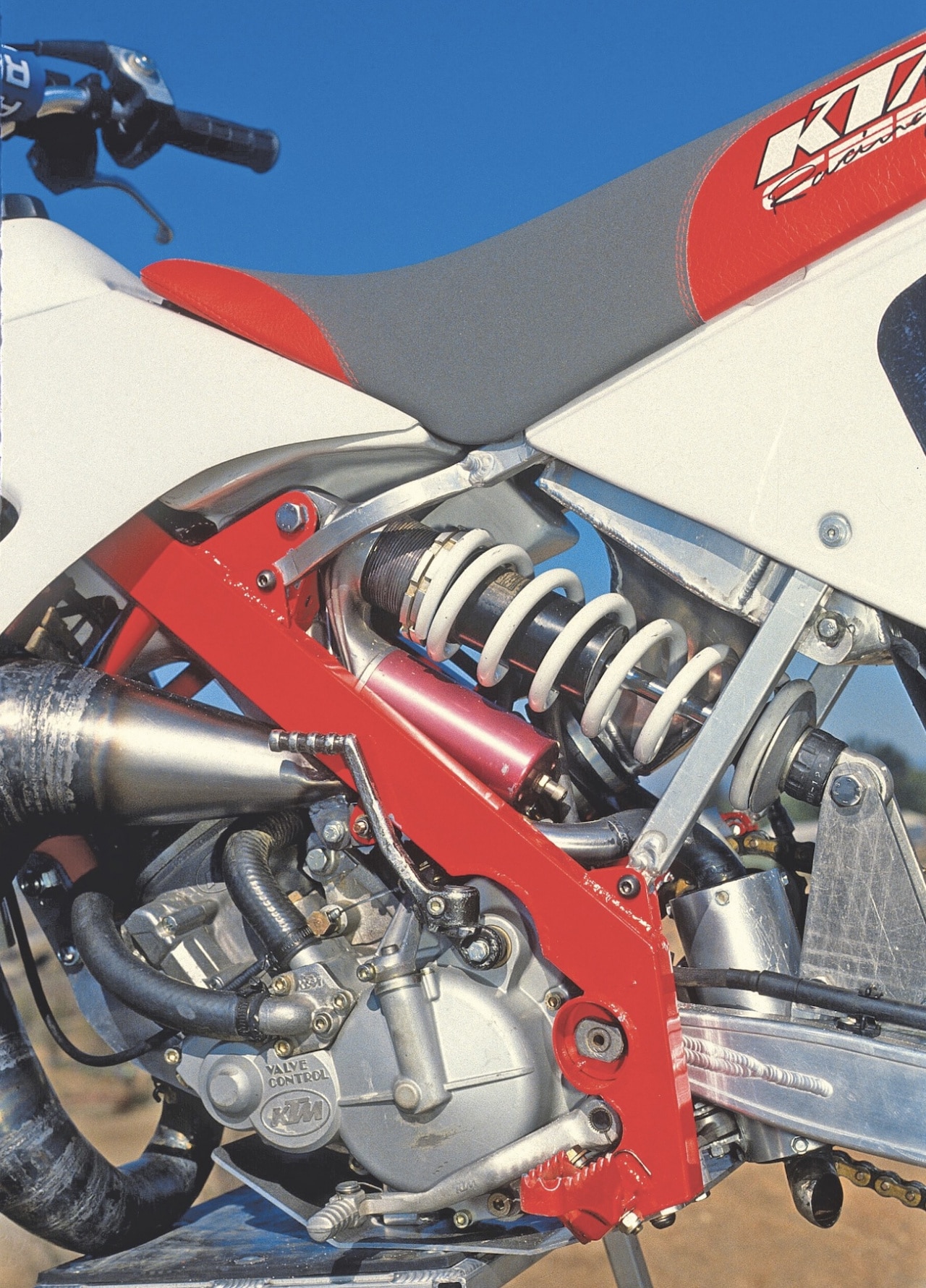

The rear suspension was the first-ever no-link, single-sided, laid-down-shock motocross suspension ever designed. The rear suspension got its rising rate from the position of the shock in relationship to the swingarm pivot and top shock mount. Note where the silencer exits the frame.

The rear suspension was the first-ever no-link, single-sided, laid-down-shock motocross suspension ever designed. The rear suspension got its rising rate from the position of the shock in relationship to the swingarm pivot and top shock mount. Note where the silencer exits the frame.

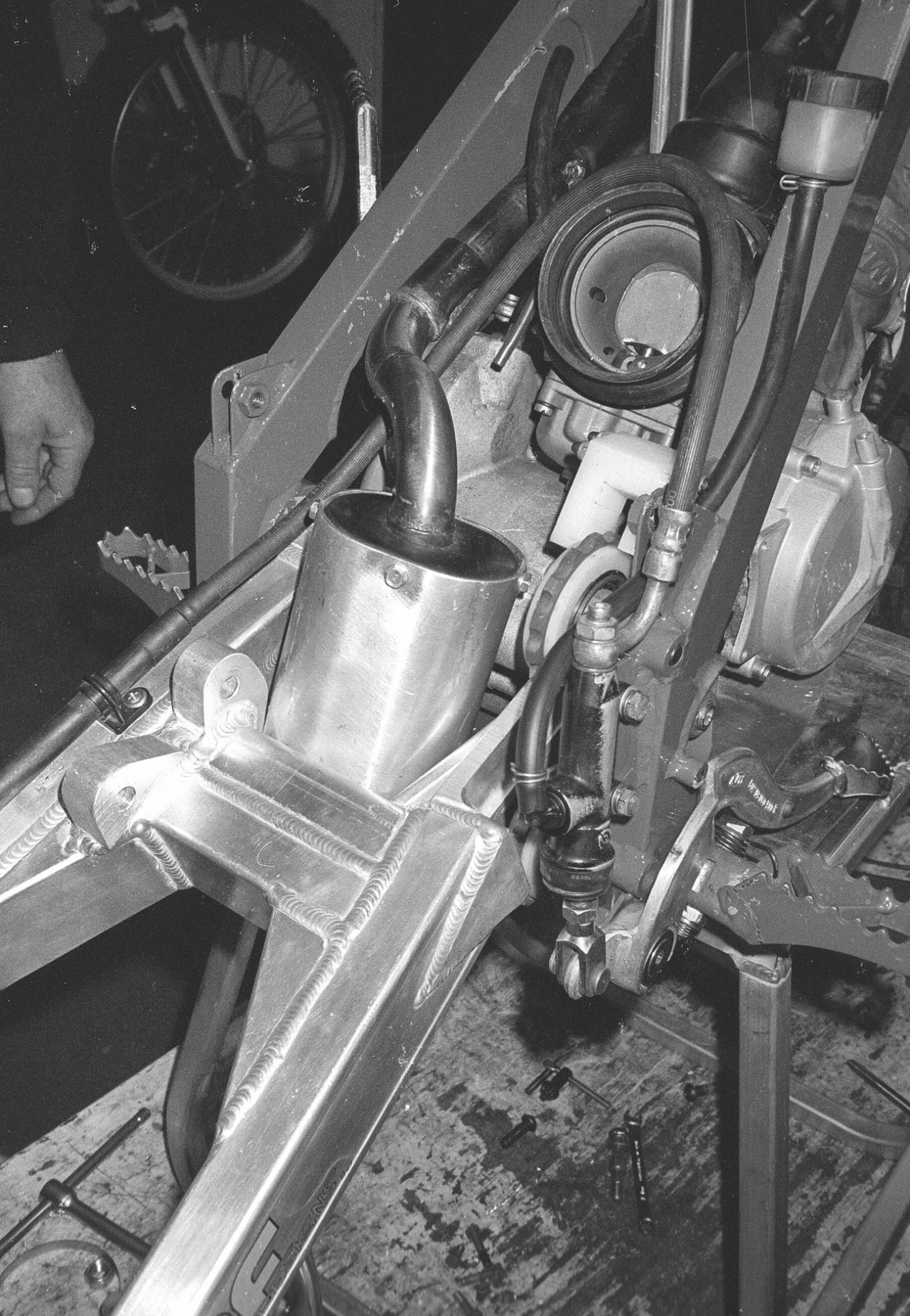

When the AMP Research KTM 125 was completed, it was almost space age for the time. It was incredibly small. Not small as in petite, but every aspect of the AMP Research bike was greatly reduced in size. The frame was something that Horst called a “parallax” frame. It was made up of only two main tubes, plus the stock KTM head tube. The two backbone tubes were large-diameter, rectangular, chromoly spars that were straight and true — sans any bends. The KTM 125 engine was used as a true stressed member of the overall layout. There were no down tubes on Horst’s frame, and the footpegs and swingarm pivot mounted to uprights that also served to hold a CNC-machined aluminum bridge that tied the bottom of the frame together. It was simple in design but intricate in terms of engineering savvy. To remove the complete engine from the AMP Research 125, all a mechanic had to do was pull the swingarm pivot bolt and front motor-mount bolts. Gravity took care of the rest.

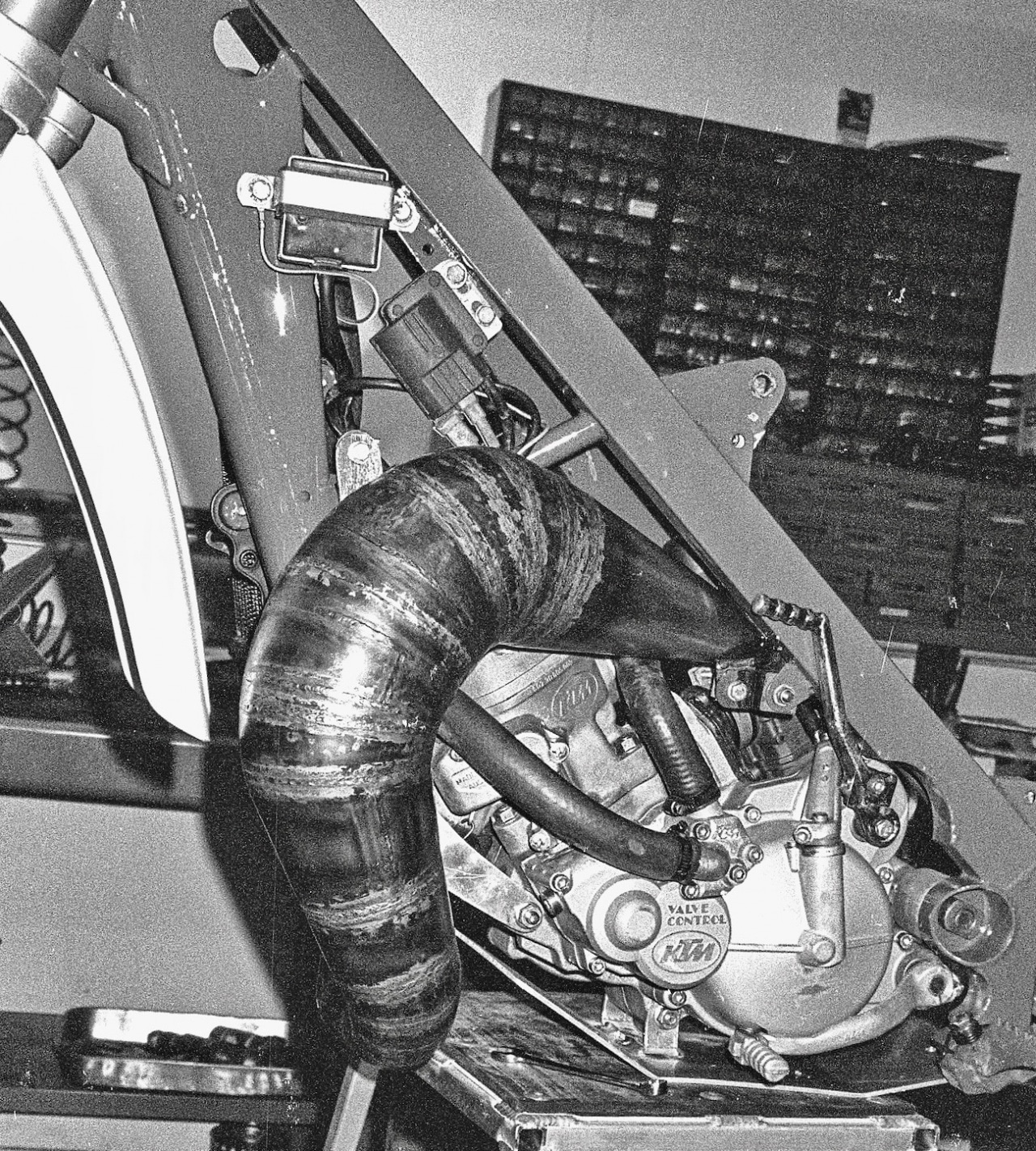

The silencer did not extend out the back of the AMP Research 125, but instead was routed downwards through the swingarm.

The silencer did not extend out the back of the AMP Research 125, but instead was routed downwards through the swingarm.

This unique chromoly frame came seven years before the era of twin-spar aluminum frames. Ahead of its time, the parallax frame was the most visible part of the 125 prototype but not the most inventive. Here’s a list of the AMP Research KTM 125’s features:

(1) The complete bodywork was only 10 inches wide at the rider’s knees.

The gas tank was designed to plug into the frame and sit on the chromoly spars.

The gas tank was designed to plug into the frame and sit on the chromoly spars.

(2) The fiberglass gas tank plugged down into the main tubes, but it did use a KTM gas cap per edict.

(3) There was only one radiator—on the right side of the bike. The design called for a longer radiator on the right side because the exhaust pipe went up into the space where the left-side radiator would have been (if there had been one).

(4) The exhaust system did not extend out of the rear of the bike. Instead, it snaked over the left side of the engine, and the stinger and silencer were tucked down through the opening in the swingarm where the shock would normally sit.

Although the AMP Research project for KTM was top-secret, Horst had the MXA wrecking crew ride it and shoot photos before it was crated up and shipped from Laguna Beach to Mattighofen, Austria. It turned out to be a good thing because the bike disappeared for almost 30 years after Horst let us ride it.

Although the AMP Research project for KTM was top-secret, Horst had the MXA wrecking crew ride it and shoot photos before it was crated up and shipped from Laguna Beach to Mattighofen, Austria. It turned out to be a good thing because the bike disappeared for almost 30 years after Horst let us ride it.

(5) The exhaust could exit through the swingarm because there was no shock linkage. Instead, the WP shock was mounted on the left side of the parallax frame to aluminum bosses on the stock KTM swingarm. It was a no-link single-shock design that obviously had an effect on future KTM suspension designs. As with all no-link, single-shock designs, of which this was the first major effort, the shock could be removed from the chassis by loosening two bolts.

(6) The stock KTM engine had right-side drive, with the chain on the opposite side compared to modern machines. This layout is what gave Horst room to run the exhaust pipe down the left side of the engine and to install his anti-chain torque AMP link chain rollers. The science behind reducing chain torque is complex, but only the late Eyvind Boyesen and Horst Leitner had any experience with trying to defeat chain snatch.

New England’s Joe Waddington was the AMP Research test rider.

New England’s Joe Waddington was the AMP Research test rider.

WHY NOT? IN ONE OF THOSE CATCH-22s THAT CAN ONLY HAPPEN IN THE CORPORATE WORLD, KTM’S MANAGEMENT ASSIGNED THE IN-HOUSE DESIGN DEPARTMENT—THE ONE THEY WERE TRYING TO EMBARRASS—TO EVALUATE THE PROTOTYPE.

The AMP Research KTM 125 was shipped to Austria for testing in 1990. But, it never really stood a chance of going into production. Why not? In one of those Catch-22s that can only happen in the corporate world, KTM’s management assigned the in-house design department—the one they were trying to embarrass—to evaluate the prototype. This fail-safe was all the threatened engineers needed to ensure job security. They nitpicked the AMP Research prototype to death and even took the time to photograph every interference fit, crack in the aluminum air box mount and even a head tube crack (even though it was their head tube). In the end, the AMP Research prototype was rolled into a dark warehouse and disappeared for what everyone thought was forever, but 29 years later the bike was discovered in a garage in Austria.

This is the AMP Research prototype as it looks today. Although a few parts are missing, there is nothing major removed. In truth, it looks as though it has not been ridden more than one hour in the last 30 years. Even the original numbers are still on the front plate.

This is the AMP Research prototype as it looks today. Although a few parts are missing, there is nothing major removed. In truth, it looks as though it has not been ridden more than one hour in the last 30 years. Even the original numbers are still on the front plate.

Although the cone pipe is a little corroded, the fiberglass fuel tank, original seat and all the plastic remain intact. Those are even the original KTM radiator wing decals that were put on before the bike was shipped from Laguna Beach to Austria in 1990.

Although the cone pipe is a little corroded, the fiberglass fuel tank, original seat and all the plastic remain intact. Those are even the original KTM radiator wing decals that were put on before the bike was shipped from Laguna Beach to Austria in 1990.

As for KTM, without new products, new ideas or new sales, the company became insolvent by 1992. The banks and courts broke the company up into four separate pieces. In all truth, it is unlikely that the AMP Research prototype could have done much to save KTM from bankruptcy, but it does point to the fact that the men who ran KTM in 1990 couldn’t see far enough into the future to stay in business. Luckily for KTM, the company eventually found forward-thinking management that embraced new ideas and turned them into profits.

ATK four-strokes came in 350, 560, 604 and 605 versions.

ATK four-strokes came in 350, 560, 604 and 605 versions.

Horst designed the Scott/PBH four-stroke for the British market. Grand Prix rider Vic Eastwood did the test riding, and the bikes were manufactured in England. Unfortunately, the money ran out. However, the Scott design didn’t die.

As for Horst Leitner, he moved on to other projects. The last motorcycle he designed was the PBH/Scott RG560 four-stroke for Great Britain. Unfortunately, Scott (PBH) went bankrupt and an American firm bought the British group’s leftover stockpile of AMP-designed bikes, moved them to America and labeled them ADB Avengers. Even though Horst designed the bike, he had nothing to do with ADB. ADB was owned by Ken Wilkes, who had bought ATK from Horst years earlier. Then Wilkes sold ATK to a Utah investment group. That deal went sour, so Wilkes formed a new group to build ADB Avengers (largely because Wilkes had a stockpile of ATK parts in his warehouse).

After the Scott/PBH enterprise failed, the design was bought by a former ATK investor and sold in the United States as the ADB Avenger. It came stock with Rhino Skin plastic bodywork.

After the Scott/PBH enterprise failed, the design was bought by a former ATK investor and sold in the United States as the ADB Avenger. It came stock with Rhino Skin plastic bodywork.

But this is what the ADB/Avenger looked like naked in 1997.

But this is what the ADB/Avenger looked like naked in 1997.

Willy Musgrave was not only an AMA Pro and MXA test rider, but he also ran the production line at ATK. This, however, is not Willy on an ATK, but instead Willy is on an ADB Avenger. ADB was the acronym for American Dirt Bikes.

Willy Musgrave was not only an AMA Pro and MXA test rider, but he also ran the production line at ATK. This, however, is not Willy on an ATK, but instead Willy is on an ADB Avenger. ADB was the acronym for American Dirt Bikes.

Horst was through designing motorcycles, in large part because he quit racing at 67 years old after suffering a major concussion. The passion was gone. AMP Research moved into the automobile business where the money was significantly better. You may know some of AMP Research’s truck and SUV parts. They include the AMP Research Bed Extender, PowerStep, BedStep and AMP fuel door. In 2015, Horst retired and sold AMP Research for a reported $30 million, which included his automotive, bicycle, motorcycle and truck product line.

More than a decade before the 1998 Yamaha YZ400 brought on the four-stroke revolution, ATK owned the high-end four-stroke market. ATK made two-and four-stroke bikes in motocross, offroad and dual-sport versions (and were the only American-made dirt bikes of note).

More than a decade before the 1998 Yamaha YZ400 brought on the four-stroke revolution, ATK owned the high-end four-stroke market. ATK made two-and four-stroke bikes in motocross, offroad and dual-sport versions (and were the only American-made dirt bikes of note).

As America’s one-and-only dirt bike designer, engineer and manufacturer, Horst Leitner lived the American dream, foresaw the four-stroke movement, designed watershed offroad bikes and was so innovative that his unique and creative ideas outstripped the common vision of what a bike could be. Today, at 80 years old, he lives a life of leisure.

Horst Leitner today (left) and as a 500 Grand Prix racer in 1965 (right).

Comments are closed.