LEADING LINK OR MISSING LINK: THE AWESOME FORK THAT TIME FORGOT

The late Dave Bickers on a leading link Greeves (with an aluminum frame).

The late Dave Bickers on a leading link Greeves (with an aluminum frame).

With all the hubbub about the new generation of motocross forks, there is a fork design that time forgot — leading links. Yet, many of the motocross riders who raced or experimented with this design think that it was given the short shrift by fashion-conscious riders of the past. Roger DeCoster is among the ranks of linkage fork fans. DeCoster raced the 500 World Motocross Championships for Team Suzuki with a set of Ribi Quadrilateral linkage forks, and when DeCoster left for Team Honda in 1980, he convinced Honda to buy the rights to Valentino Ribi’s design.

Valentino Ribi works on Roger DeCoster’s works Suzuki forks.

Valentino Ribi works on Roger DeCoster’s works Suzuki forks.

DeCoster wasn’t the only rider who believed in linkage forks. During the 1960s and early ’70s, many motorcycles came with leading-link forks, often called Earles forks. Unlike the typical telescopic fork, leading links had the uncanny ability to climb over bumps and obstacles by folding their shock-absorber-suspended front link up and back with the force of the bump. Greeves, DKW, DOT, Cotton, Sachs and even BMW were big supporters of leading-link forks.

Leading links were lighter than telescopic forks, although they looked heavier. They could climb over obstacles without the fork tubes bending backwards. They had minimal stiction because of the leverage of the backwards-folding arm. If they had a flaw, it was that some early leading-link forks would stiffen and rise up under hard braking, but this problem was easily solved by making the front brake float.

BMW was a big proponent of leading link forks and many of their bikes from the 1940s through 1960s came with leading links.

BMW was a big proponent of leading link forks and many of their bikes from the 1940s through 1960s came with leading links.

If your bike didn’t come with leading links, you could buy aftermarket versions from Swenco or Van Tech. A young Jody Weisel started out racing a leading-link-equipped Sachs 125 in the late 1960s, and when he switched to Hodaka 100s and 125s, he ran aftermarket Swenco forks. Rich Thorwaldson was a factory Suzuki racer whose post-race career centered on building swingarms for 1970–’80 motocross bikes. Rich was a former desert racer who believed that leading links could be updated to work on modern bikes. His 1979 Thorks were very good, very inexpensive and very light.

ATK founder Horst Leitner working on his parallelogram motocross fork.

ATK founder Horst Leitner working on his parallelogram motocross fork.

Horst Leitner’s AMP Research mountain bike fork mimicked the design of his parallelogram motocross fork — with two arms that folded up and back when crossing rough ground.

Horst Leitner’s AMP Research mountain bike fork mimicked the design of his parallelogram motocross fork — with two arms that folded up and back when crossing rough ground.

In the early 1990s, ATK/AMP inventor Horst Leitner developed a prototype set of leading-link forks that merged the ideas of Earles and Ribi into one fork design. Leitner hoped to make the forks an option on his ATK 406 and 604 motocross bikes. Four-time 250 Champion Gary Jones was the test rider on the project, but Leitner sold ATK, and when he left, the project was shelved, although Horst revised it later on the popular AMP link mountain bike fork.

One of the prettiest bikes ever made, the 1964 Dot also had the nicest-looking leading-link forks. The chrome covered shocks added a touch of class.

One factory team even experimented with putting small leading-link forks on the bottom of a set of telescopic forks. The idea was for the leading-link arms to absorb small bumps, while the telescopics absorbed the big stuff. It never saw the light of day (outside of the factory).

When DeCoster left Team Suzuki for Honda, he convinced Honda to buy the rights to Valentino Ribi’s fork design. Honda made several CNC-machined aluminum prototypes (including on this twin-cylinder RC125), but shelved the idea because of its complexity and cost.

So, what happened to leading-link forks? Back in the 1970s, the improvement of telescopic forks made the leading links look old fashioned—and, as often happens, the riders of the era deserted leading links for the next big thing. Honda built several exotic, CNC-machined, ultra-light versions of the Ribi design but decided that the motorcycle market wasn’t ready for such a radical-looking idea.

The 1967 Greeves Challenger leading-link forks were the most popular. You might also notice the cast-aluminum downtube.

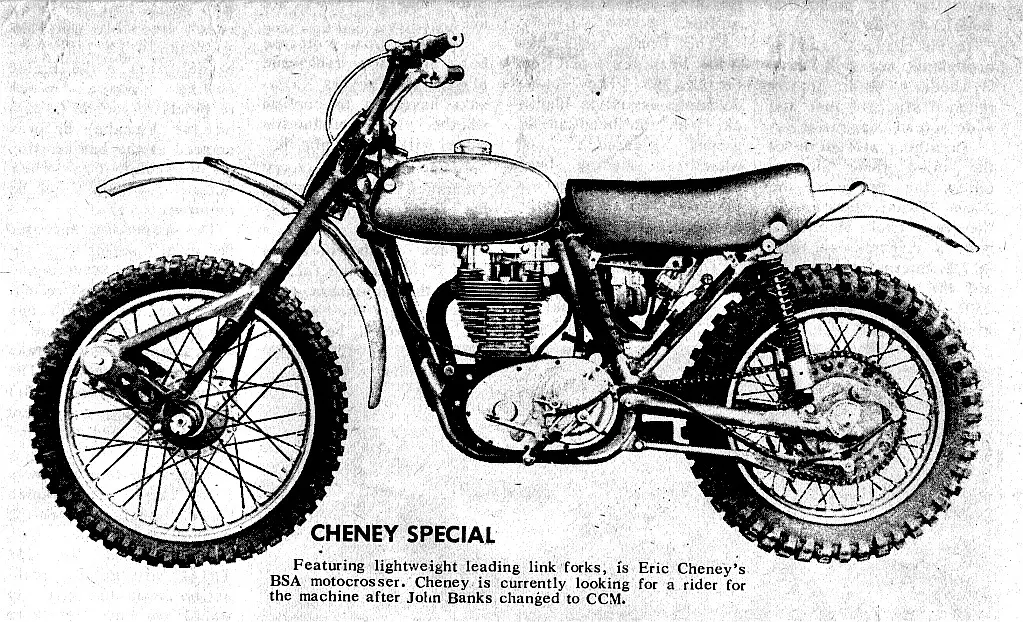

Cheney combined the four-stroke, air shocks and leading link craze into one definitive Yamaha-powered machine. The forks were a spin on Ribi Quadrilaterals.

This is an Italian made Villa MX250 with aluminum Ribi Quadrilateral forks. The forks were built way before Honda bought the design from Valentino Ribi.

This is an Italian made Villa MX250 with aluminum Ribi Quadrilateral forks. The forks were built way before Honda bought the design from Valentino Ribi.

The Cotton Cobra came equipped with Armstrong leading links.

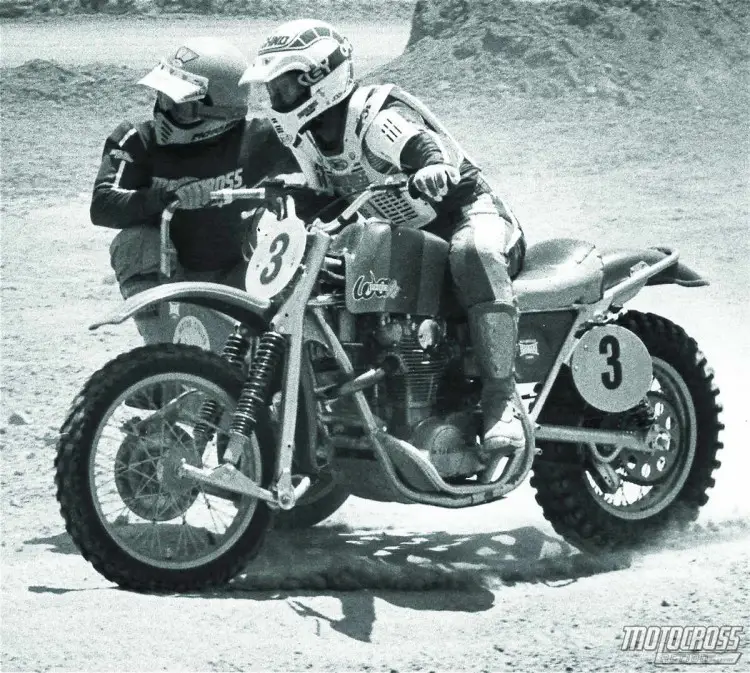

Most sidecarcross bikes still use leading links to hold up the mass of a big bore engine and two men. Here, Jody Weisel powers a Yamaha 650 twin engine Wasp to second in the 1983 California Sidecar Championships.

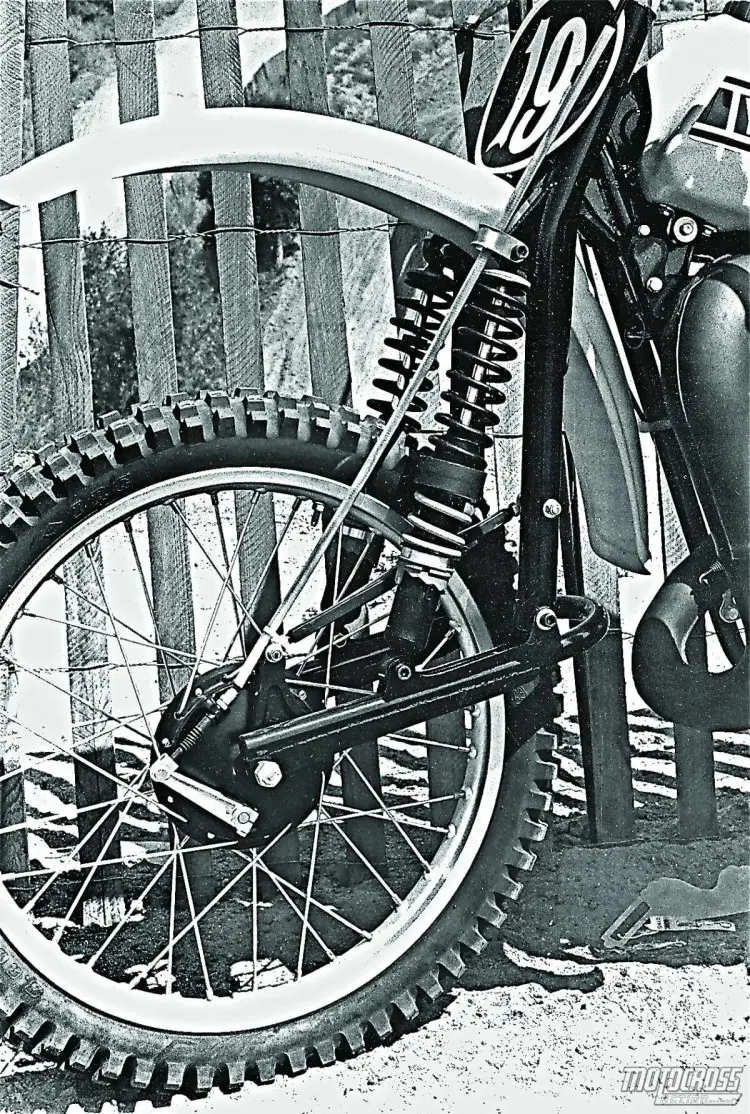

Technically these Cheney forks are trailing link, but the concept is the same.

Technically these Cheney forks are trailing link, but the concept is the same.

This is a Hodaka Super Rat with Swenco leading link forks. The Swenco forks were an aftermarket bolt-on that used the stock triple clamps to hold the chromoly fork legs. The front swingarm was cast aluminum. The shocks were Curnutts.

This Greeves Griffon 380 was one of the last bikes out of the Greeves factory with leading links in the mid-70s. Telescopic forks were rapidly replacing leading links.

The German-built Sachs/DKW 125 was one of the first popular purpose-built 125 motocross bikes sold in America. It originally came with leading-link forks, but most riders opted for the optional telescopics when they were made available.

The late Rich Thorwaldson’s Thorks (for Thor forks), were 4 pounds lighter than the 36mm telescopic forks of the day. The Thorks used two S&W Stroker II shocks and featured 11 inches of travel. Thorks retailed for $375 without shocks or $475 with shocks. Note the floating front brake that stopped the fork from rising under braking.

MXA test rider Lance Moorewood rails a Saddleback berm on a 1980 Yamaha YZ250 outfitted with Thorks and a Fox air shock. The shocks on the Thorks are by S&W.

Dan Alamangos’ restored 1979 Yamaha YZ125 with Thorks and a Fox AirShox.

Dan Alamangos’ restored 1979 Yamaha YZ125 with Thorks and a Fox AirShox.

Comments are closed.