MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE GRANT LANGSTON’S 2004 KTM 250SX TWO-STROKE

We get misty-eyed sometimes thinking about past bikes we loved and those that should remain forgotten. We take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and disregarded in the MXA archives. We reminisce on a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our test of Grant Langston’s 2004 KTM 250SX.

In the 2003 Supercross season, everyone thought Grant Langston’s KTM 250SX was the cause of his abbreviated introduction to 250 Supercross. There is no doubt that Grant hit the ground with alarming regularity, or that his 250 Supercross debut was over before it even got started. But, the MXA wrecking crew didn’t believe that the bike was to blame.

Larry Brooks (the KTM team manager at the time) hired a full-time test rider to help put time on the race bikes. Test rider Casey Lytle turned in lap after lap on the KTM 250SX, while Grant was off winning the 2003 AMA 125 National crown on his much-beloved KTM 125SX. Brooks, a former AMA Pro, even took up the mantle as test rider when push came to shove. With each passing week, we heard reports through the pipeline that the bike was getting better and better.

We take that kind of rumor with a grain of salt. Who wouldn’t (with the possible exception of internet mavens)? Our first view of Grant Langston’s new-and-improved KTM 250SX would come at the opening round of the 2004 Supercross in Anaheim. His performance didn’t make believers out of us. At Anaheim 2, things got better and Grant actually cracked the top 10. By San Francisco, he made it into the top five. A podium looked possible, but then things unraveled in Houston. People started blaming the bike again, and it started looking like 2003 all over again. The MXA gang had gone to every Supercross, and we thought Grant’s rash of crashes looked more like pilot error than bike induced. We’re not knocking Grant. We just don’t want the bike to get a rap it doesn’t deserve (and honestly, neither does Grant). He is the first one to admit that he loves the bike. He bugs the KTM guys all the time to go riding. That was something he never did last year.

THE MXA TEST CREW IS AS CRITICAL OF BIKE PERFORMANCE AS ANYONE ON EARTH, BUT THE ONLY REAL TEST WOULD BE TO THROW A LEG OVER LANGSTON’S 2004 SUPERCROSS SLED FOR OURSELVES.

The MXA test crew is as critical of bike performance as anyone on earth, and while gossip is the lifeblood of idle minds, the only real test of the truth would be to throw a leg over Langston’s 2004 Supercross sled for ourselves.

If you looked closely at Langston’s works KTM, it was a thing of beauty, replete with all the bells and whistles that make a bike special. The orange plastic looked amazing. The graphics were clean. The suspension was humongous (front and rear). RG3’s four-post triple clamps housed the 52mm WP forks. The engine had an electronic power valve (and the small battery that was required to operate it). Renthal FatBars gave Grant the bend he wanted. Tag Metals grips were mated to the FatBar. A beryllium Brembo front brake caliper handled the braking duties and put the whole package over the top. KTM had definitely come a long way since Mike Fisher was its one factory Supercross racer in 1991.

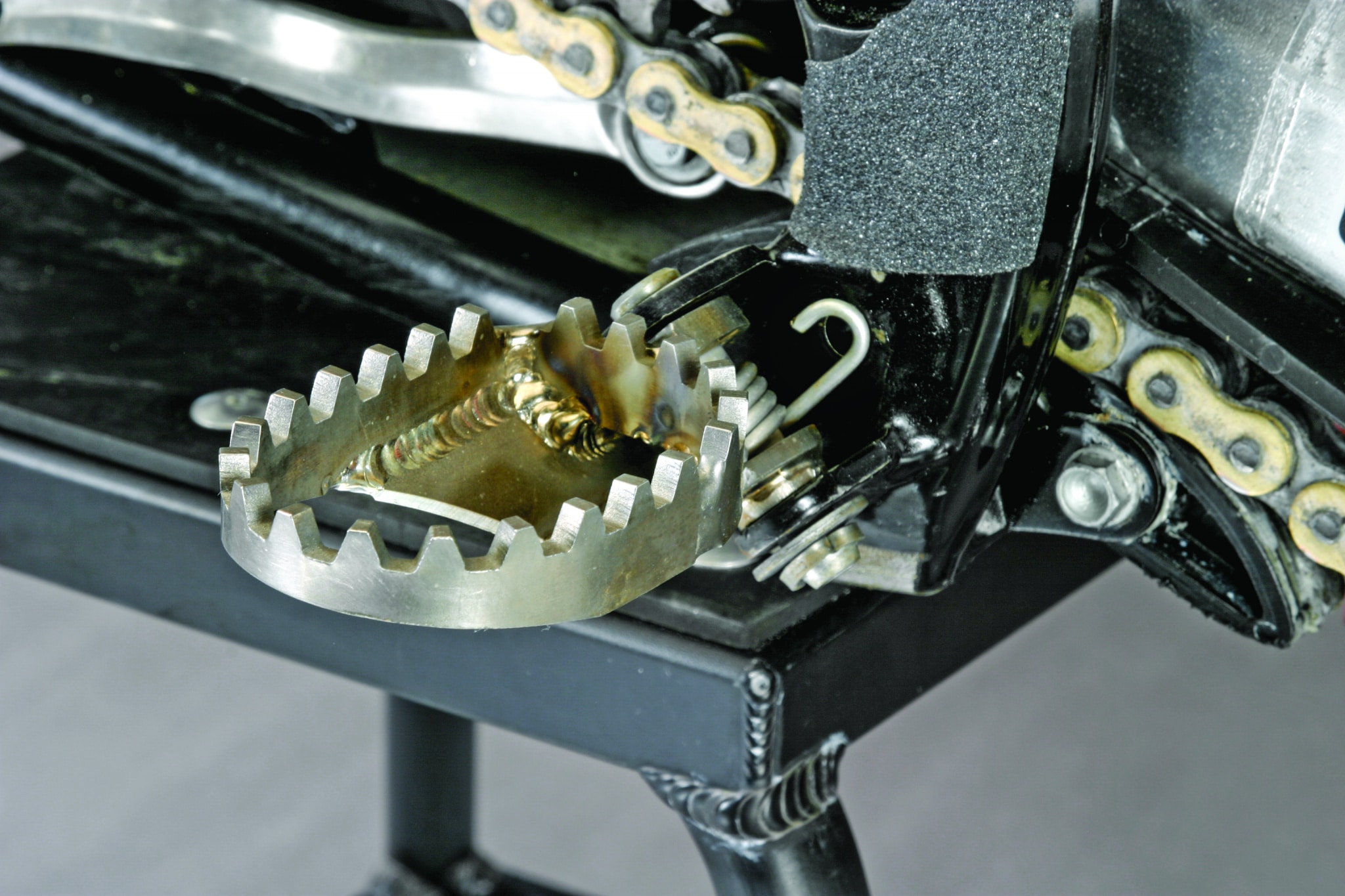

Something we found interesting was that one of Grant’s footpegs was taller than the other. It turned out one of Grant’s legs is a little shorter than the other, and after a hard day of riding Grant’s back would hurt because he was always putting more weight on one foot. The tall footpeg fixed his problems.

In the past, we have had good luck testing Langston’s bikes. The first was his 2001 KTM 125SX. The second was his 125 National Championship-winning 2003 KTM 125SX. To get our hands on his 2004 KTM 250SX, all it took was one phone call. Larry Brooks and the KTM crew were pleased with the work they’d done and were dying to have someone outside their camp ride it. We just so happened to be the someones.

Rather than send out every person involved with Langston’s bike, KTM sent a lone mechanic into our midst. That mechanic just happened to be Paul Delaurier, one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet. While we normally have to change bar and lever positions on factory riders’ bikes, because they always have one weird quirk or another, we didn’t have to touch a thing on Langston’s bike. The bars were in the perfect spot, and the levers were nice and level.

Before our test riders jumped aboard, Paul Delaurier had to explain the on/off switch on Grant’s bike. Almost like the key for your car, you have to turn Grant’s motorcycle on before you start it. You still have to kickstart it, but before you do that you have to turn on the electronic power valve. Likewise, when you stop, you have to turn it off or the little battery that powers it will run out of juice. Before we could do any laps, the bike had to be warmed up. Not warmed up to the boiling point like Chad Reed’s works YZ250, but warmed up to operating temps.

Within the first lap, it was very evident that the suspension was stiff. Really stiff. Both the front and rear moved, but not very much, and the rear had a slight tendency to kick under deceleration. Supercross demands this type of setup, so we weren’t all that surprised. We’ve ridden Grant’s outdoor stuff enough to know that his setup is pretty soft for a pro racer. We could have spent some time clicking both the forks and the shock, but, honestly, we didn’t want to stop riding.

THE ENGINE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM WAS THE THROTTLE; ROLL IT ON, ROLL IT OFF. IT DID ALL THE WORK. WITH GRANT’S ENGINE, ALL YOU HAD TO WORRY ABOUT WAS AIMING THE BIKE.

Why, you ask? Grant’s engine was absolutely amazing. It picked up instantly with no noticeable hit. It just started going and continued to pull all the way through the midrange. When it finally gave up the ghost, it was way up in the rev range. It only took one word to describe Langston’s powerband—“linear.” You didn’t have to worry about staying on the pipe, preparing for the hit or getting on the throttle early. The engine management system was the throttle; roll it on, roll it off. It did all the work. With Grant’s engine, all you had to worry about was aiming the bike.

How much of the powerband’s prowess was the result of the cobbled-together electronic power valve? Not as much as you’d think (at least not in the horsepower department). The electronic gizmo helped make the engine run the same every time. A standard power valve can snap open rapidly one second and slower the next. The electronic power valve kept the motion consistent.

With the engine helping us get into the corners faster, we need to mention the front brake. The faster you can stop, the faster you can go. Grant’s brake was a nose-wheelie implement. We respected it.

As for the much-talked-about KTM handling, it wasn’t a problem. Langston’s RG3 triple clamps had a 16mm offset, which pulled the front wheel back, shortened the front center, increased trail and put more weight on the contact patch. This was not mumbo-jumbo geometry. It was exactly what local racers have been doing for years. We didn’t suffer from the normal push that KTM’s engineers had been unable to tame; instead, the layout of Grant’s bike, including the shock length, head angle, trail and fork setup, produced a very quick-turning bike.

Is this bike to blame for Grant’s erratic performances in 2003, which have included leading most main events and crashing out on occasion? No. Grant had a steep learning curve in his move up to the big-boy class; but, he definitely has the horsepower, handling and suspension to get the job done.

Comments are closed.