MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE JAMES STEWART’S 24-0 NATIONAL-WINNING KAWASAKI KX450F

James Stewart had a perfect National season on this Factory KX450F.

James Stewart had a perfect National season on this Factory KX450F.

We get misty-eyed sometimes thinking about past bikes we loved, as well as ones that should remain forgotten. We take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and disregarded in the MXA archives. We reminisce on a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our test of James Stewart’s 24-0 National-winning 2008 KX450F.

Perfect—a condition of complete excellence, as in skill or quantity; faultless; most excellent. Perfection in motocross has been defined by utter dominance, void of error, not losing. Out of the thousands of professional racers who have earned a paycheck by lining up on a motocross gate, only two have been perfect. Ricky Carmichael came first, completing the unthinkable 24-0 National series in 2002. RC was perfect again in 2004.

Four years later, after several years of being stymied by injuries and crashes, James Stewart began the 2008 outdoor series on a freshly healed knee and ended the 450 Nationals by winning every single moto of every single race—24-0. Towards the end of the perfect season, rumors began circulating that Stewart would leave his lifelong Kawasaki home for a slot on the San Manuel/Yamaha Supercross-only team.

This was devastating news for Kawasaki, but the ever-enterprising MXA wrecking crew saw it as an opportunity. With the sun setting on James Stewart’s career with factory Kawasaki, the wrecking crew approached the green team about giving us Stewart’s 24-0 KX450F. They said “Yes” and gave us the opportunity to be the last riders to sling a leg over Stewart’s KX450F before Kawasaki packaged it up to put on display for the masses. On a side note, we also were the last riders to put the hammer down on the 2004 Honda CRF450 that Ricky Carmichael raced to his perfect season (it, too, was headed for a museum).

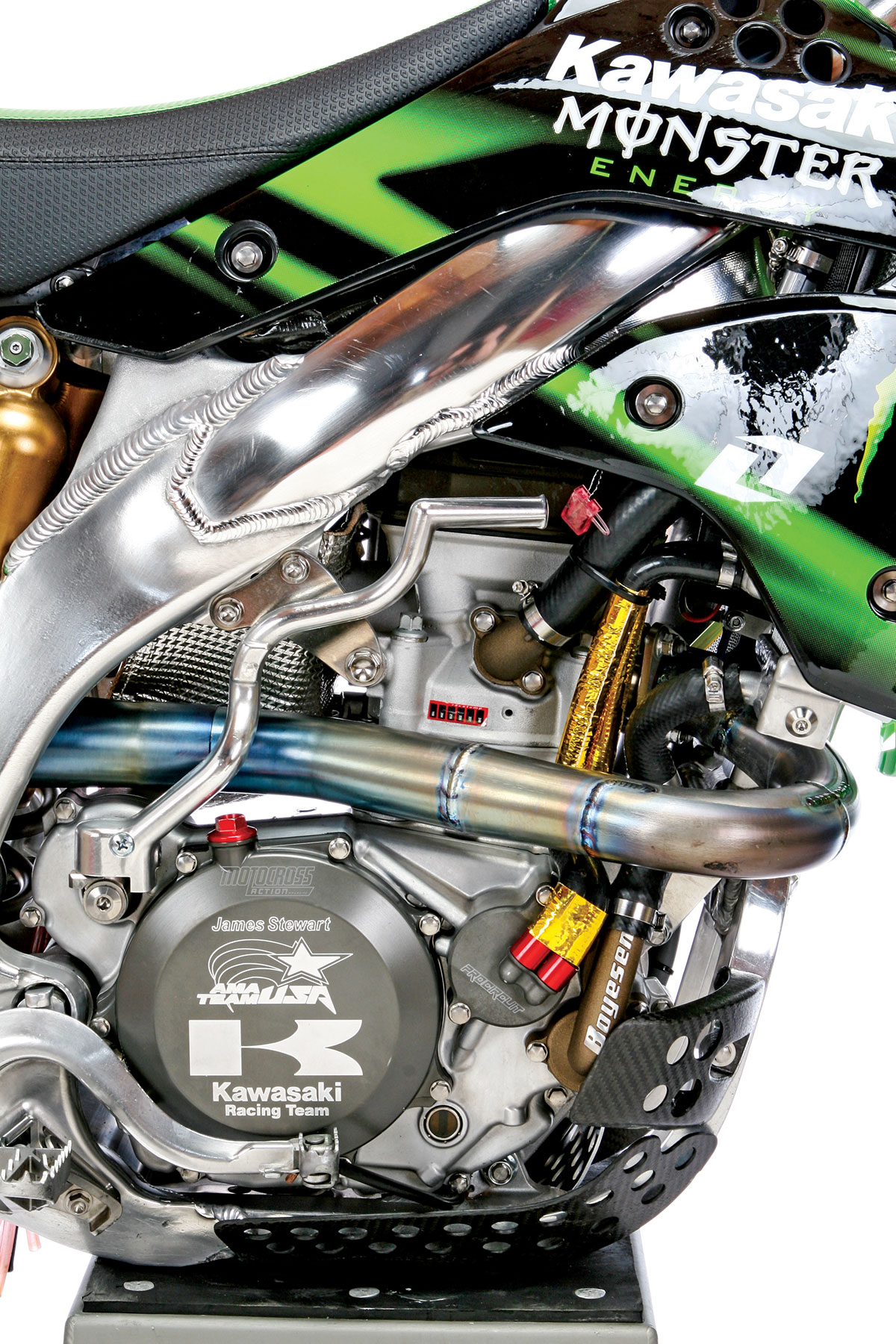

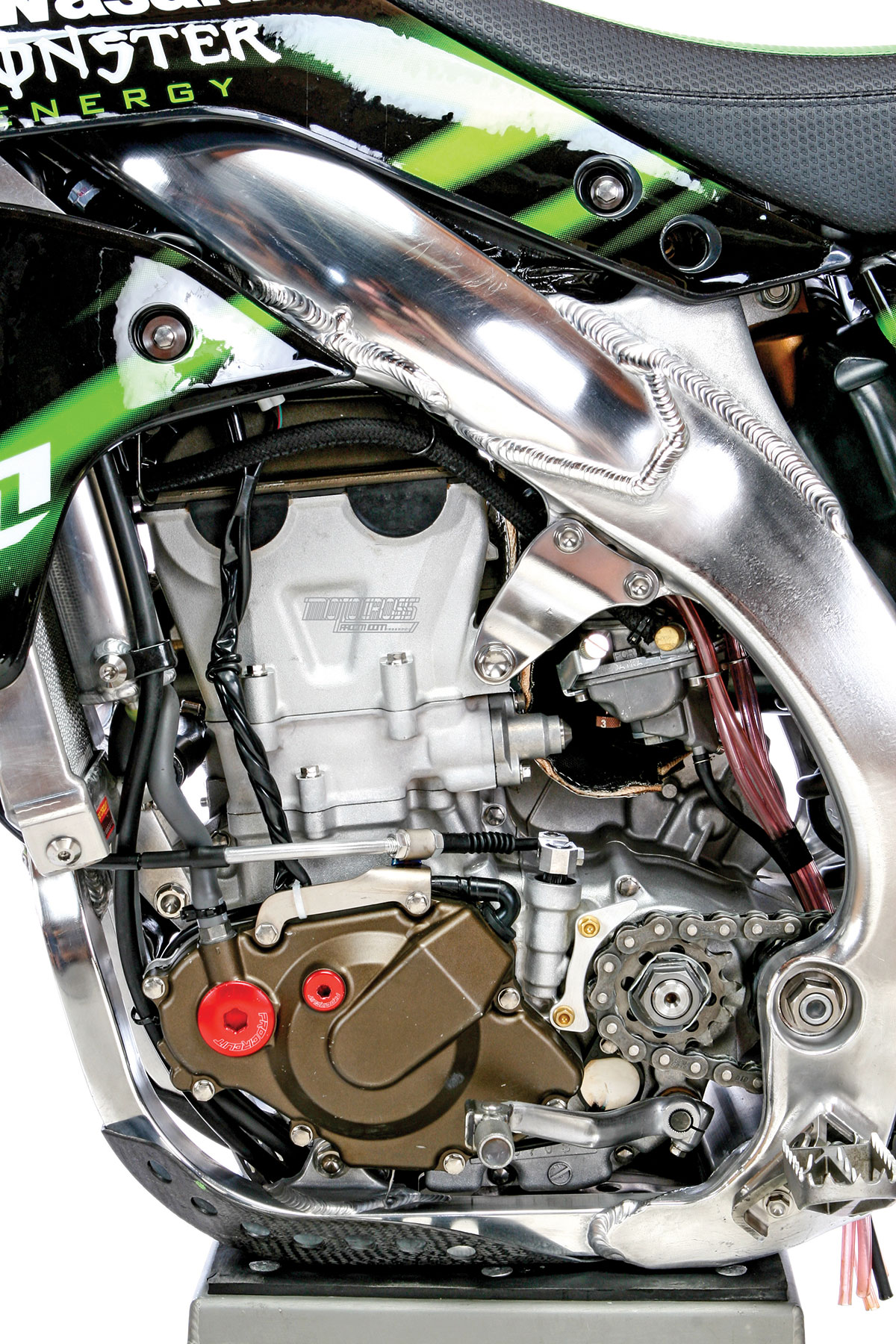

SHOP TALK: WHAT PARTS WERE WORKS? What parts do you wish that you could buy but can’t? At the head of the list are the Kayaba suspension, engine internals, link arm, aluminum hubs, beefy clutch arm, aluminum triple clamps, radiators, radiator recovery tank, oil cooler, four-speed transmission, footpeg mounts, magnesium front brake, titanium shock spring, polyurethane chain guide, Bridgestone tires and factory 270mm front and 240mm rear oversize brake rotors.

WHAT PARTS WERE AFTERMARKET? Kawasaki relied on an assortment of aftermarket companies to strengthen the KX450F package. Pro Circuit handled the exhaust system, holeshot device and engine plugs. A Hinson clutch basket was employed, as were a D.I.D. chain, Dirt Star rims, Renthal 997 TwinWall handlebars, Renthal medium-density half-waffle grips, Renthal sprockets, One Industries graphics and seat cover, an NGK spark plug, a Boyesen water pump cover, ARC folding levers, and an Acerbis vented front fender and carbon fiber front disc guard.

WHAT PARTS WERE PRODUCTION?

Kawasaki didn’t use very many stock parts, but you might be surprised to discover the parts that they elected to keep production. The most surprising stock parts were the footpegs, which are rather narrow and fail to offer great traction. They were sharpened to improve traction. The other major stock parts were the skid plate, brake pads, airbox, castings and parts mandated by the AMA production rule.

WHAT WAS UNIQUE ABOUT STEWART’S SETUP?

James Stewart’s former mechanic, Mike Williamson, warned us that it would take time to adapt to Stewart’s setup. He was right. What was the biggest hurdle that we had to overcome? James Stewart likes his levers pointed toward the ground. The levers were rotated downwards 3 inches from the more common horizontal position. After catching so much flack from sensitive readers for moving Ricky Carmichael’s levers on his museum-quality 2004 Honda CRF450, we decided to leave Bubba’s levers alone and tough it out.

Stewart also had his bar mounts positioned 5mm back from stock, which gave taller MXA test riders the sensation that the handlebars were in their laps. Finally, James had his seat cut 15mm, used a seat hump, and cut his subframe 10mm. What do these preferences say about Stewart? Not only does he stand up quite a bit (low levers), but he has a very neutral riding position when seated (location of seat hump and farther back bar mount position).

WHAT WAS THE COOLEST THING ON JAMES STEWART’S KX450F? We could go on and on about Stewart’s works suspension, but that answer would be too easy. In reality, there were several parts that we were enamored with.

(1) Oil cooler. Stewart’s KX450F comes with an oil cooler straight from Kawasaki of Japan. By now, oil coolers are standard on most National-caliber bikes, but the intricate routing system that Kawasaki uses is impressive.

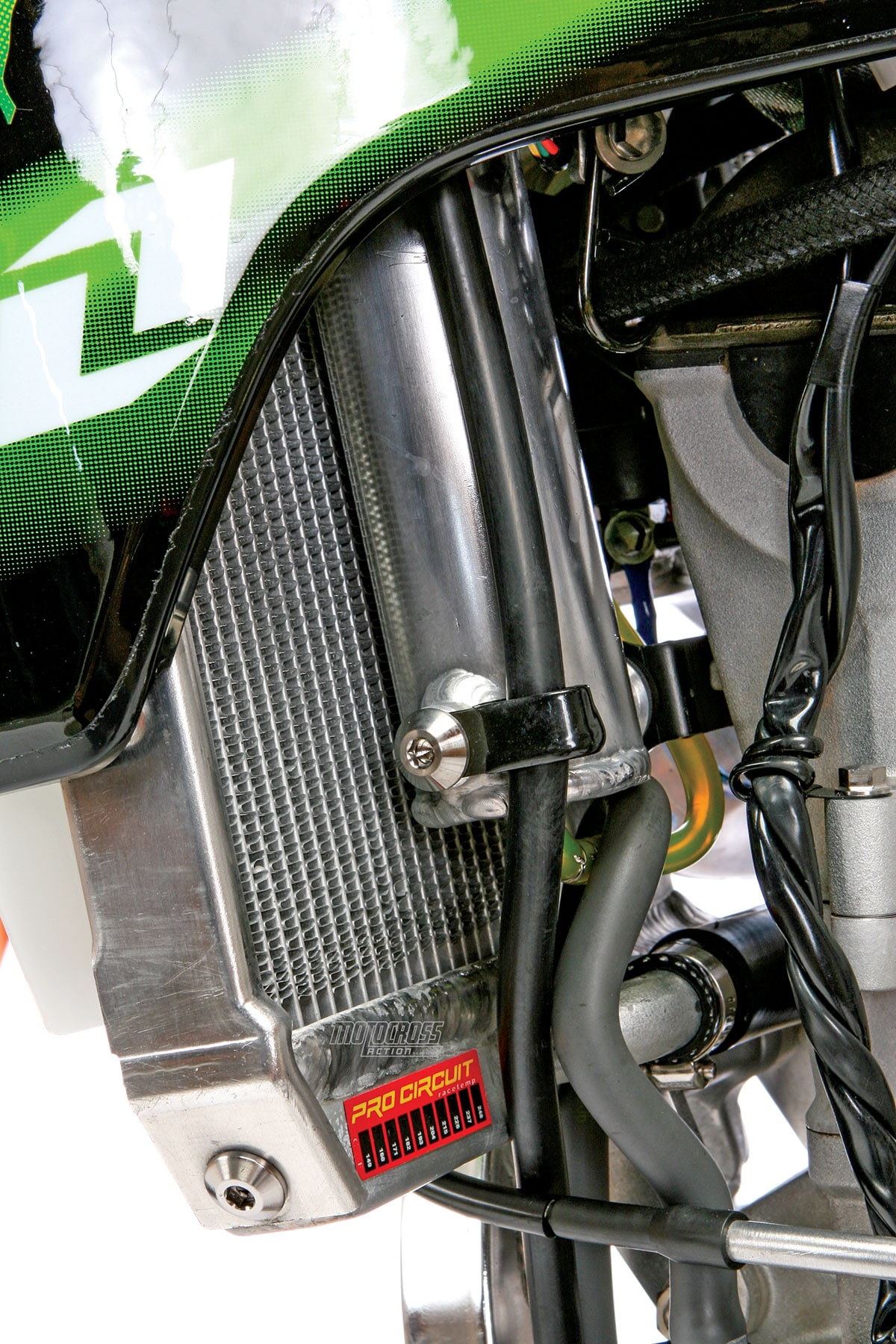

(2) Right-side radiator. Heat steals horsepower, which is why Stewart’s KX450F has a larger right-side radiator to allow for increased fluid volume and airflow. Both radiators also come with special braces to prevent a costly DNF from damage due to a crash.

(3) Titanium bolts. We aren’t in love with the idea of spending thousands of dollars on titanium hardware for our bikes. Not only is it expensive, but titanium changes the rigidity of a bike (depending on where titanium is used), and weight reduction can be accomplished by much cheaper means; however, factory Kawasaki spared no expense on Stewart’s KX450F. Every bolt (save for the steel swingarm pivot bolt) was titanium. Also on the titanium list were the front spokes, shock spring and footpeg mounts.

Factory Nissin front brake caliper.

Factory Nissin front brake caliper.

(4) Radiator catch tank. Kawasaki uses a self-siphoning radiator catch tank. The catch tank is pressurized. After excess fluid enters the tank (when the bike is hot), the fluid siphons back into the radiator (once the bike cools down). Valuable fluid is never lost, meaning that Stewart’s bike was free and clear of any engine failures due to radiator fluid boil over.  The polished frame.

The polished frame.

(5) Looks. James Stewart’s KX450F was so clean that we would have eaten off of it. Mechanic Mike Williamson used serious elbow grease to make sure that every square inch of the bike was perfect. The frame was buffed to a mirrored finish. The stock footpegs were bead blasted and sharpened, and even the radiator braces (items that were barely visible to the naked eye) had been buffed to a shine.

HOW FAST WAS IT? There’s a common misconception about factory bikes. Everyone—and we mean everyone—believes that works bikes belch fire and spit flames; that a works engine is built for peak horsepower and horsepower alone. Wrong! We’ve tested a 60-horsepower Honda CRF450 before, and while we bragged about the number of ponies that it pumped out, test riders couldn’t hold on to it for more than a few laps. There comes a point where too much horsepower under the plastic is counterproductive. With that said, James Stewart’s KX450F was a perfect mix of power and breadth. The factory engine was potent from the midrange well into the top end, but down low it was very manageable. Test riders could roll on the throttle without worrying that their arms would be torn from their sockets. Too much power off the bottom would have caused the rear tire to light up like a dragster without the benefit of gaining traction. Stewart’s engine was, dare we say, pleasant down low, meaty in the middle and a screamer up top. The longer test riders held the throttle on, the better the entire KX450F package worked. The suspension began to move. The under-steering issue caused by the 25mm offset clamps started to fade, and the powerband kept pulling without any indication of signing off. The engine profile made it an advantage for any skilled rider.

Pressurized catch tank.

Pressurized catch tank.

HOW WAS THE SUSPENSION? The KYB units were as soft as a feather bed—a feather bed filled with concrete. Stewart’s 49mm Kayaba forks were made to soak up bomb holes and braking bumps without shuddering. In order for us mere mortals to get the forks to budge, we had to over-jump obstacles and plow into bumps without fear. When we did, the forks offered tremendous bottoming resistance. And while they weren’t, by any means, plush, they were predictable and semi-comfortable; however, this success was far overshadowed by the inability of the suspension to soak up small chop. We aren’t ignorant, though. We know that while we felt every wrinkle and crease on the track, Stewart would skip through the same succession of ruts and chop without thinking twice. Regardless of how stiff the Kayaba forks were, the front end and shock were very well balanced. The shock shaft was remarkably bigger than a stock unit, and while Kawasaki technicians wouldn’t spill the beans on the shaft’s diameter, suffice it to say that it’s at least 1/3 bigger than the stocker. The 148-pound Stewart ran 100mm of sag during his run to perfection in the outdoor series. Interestingly enough, Kawasaki mechanics admitted that James couldn’t effectively use the suspension when he was going slower than his normal race speed.

There might have been a lot of things we didn’t like about Stewart’s Factory KX450F, but like it or not, Stewart went 24-0 without our help.

There might have been a lot of things we didn’t like about Stewart’s Factory KX450F, but like it or not, Stewart went 24-0 without our help.

HOW WAS THE GEARING ON STEWART’S KX450F? We weren’t surprised that Stewart’s KX450F had a four-speed transmission. Why? First of all, we had previously tested Tim Ferry’s KX450F, and it had a four-speed. Second, in 2007 and 2008, James opted for the four-speed tranny that came stock in 2006, because the fifth gear was superfluous (in that it was too tall to add anything useful for motocross). The breadth of the powerband afforded James the ability to use all four gears.

Of course, James’ KX450F doesn’t use the stock wide-ratio gears. How do we know this transmission setup is effective? When testing Stewart’s bike on a rather fast motocross track, we didn’t even touch fourth gear, meaning that only the longest straights of a National track would require shifting to top gear on the KX450F.

Stewart’s Factory KYB suspension setup was as hard as concrete for our testers.

Stewart’s Factory KYB suspension setup was as hard as concrete for our testers.

WHAT DIDN’T WE LIKE? That’s easy. For everyone but James Stewart, this bike is too stiff. The levers are too low, and it pushes way too much in the center of corners.

WHAT DID WE LIKE? The powerband.

WHAT DO WE REALLY THINK? It wouldn’t be proper for us to say that James Stewart’s bike setup is wrong. Yes, the suspension was extremely stiff for all but the fastest pro riders on the planet. Yes, there was an even greater push in the front end due to the 25mm offset clamps (compared to the stock 24mm offset); however, these traits posed no problems for Stewart. Most of us will never know the feeling of compressing the trick 49mm Kayaba works suspension so far that the 25mm offset clamps actually offer precise turning. Testing James Stewart’s perfect 24-0 National bike was a thrill, and its historical significance made us proud to have ridden it, but it wasn’t the most fun bike for us to ride.

Comments are closed.