SEVEN DAYS IN MATTIGHOFEN WITH THE MXA WRECKING CREW

BY JOSH MOSIMAN

Members of the MXA wrecking crew have seen the KTM headquarters in Austria at different stages of its growth. Jody Weisel visited the Mattighofen factory back in 1982. Daryl Ecklund went in 2014, and now I had the chance to go in 2023. I think I had the best tour of all, though, because I brought the whole band with me. MXA test riders Dennis Stapleton and Josh Fout, as well as our digital editor, Trevor Nelson, joined me for the trip of a lifetime.

I CAN TRULY SAY THAT I FOUND THE KEY TO KTM’S SUCCESS WHILE RACING AT THE MEHRNBACH NATIONAL. IT IS BECAUSE KTM IS

MANNED BY PASSIONATE EMPLOYEES WHO RACE THEMSELVES.

A lot has changed since Jody visited Mattighofen in 1982. At that time, KTM was a conglomerate that included motorcycles, bicycles, radiators and metal tooling, but the financial downturn of the late 1980s left KTM in serious debt. The company went through several ownership changes and eventually fell into the hands of a consortium of creditor banks in 1991. With bankruptcy looming, the banks split KTM into four different companies and sold each off separately. The four new companies were KTM Sportmotorcycle GmbH (motorcycles), KTM Fahrrad GmbH (bicycles), KTM Kühler GmbH (radiators) and KTM Werkzeugbau GmbH (tool making). In 1992, Stefan Pierer’s Cross Holdings bought the KTM motorcycle division to save it and took over the tooling division soon after (the tooling company was needed to produce motorcycle engines).

At the time Daryl went to visit Mattighofen seven years ago, they had just bought Husqvarna and were growing aggressively. Since Daryl’s visit, the factory has expanded. The Motohall Museum was added. The number of employees skyrocketed. The Pierer Mobility Group absorbed GasGas into its production lines, and the company expanded into the electric mountain bike market as well with Husqvarna and GasGas e-bicycles. The only reason Stefan Pierer doesn’t sell KTM electric bicycles is because, when he bought KTM to save them from bankruptcy, the KTM bicycle segment was bought by the Urkauf family, who still owns the rights to KTM bicycles today. Some of the confusion about which company is owned by whom is because the motorcycle and bicycle companies both have orange as their corporate colors, use the same logo and are based out of Mattighofen. When you drive into the town of Mattighofen, the first building you see off Highway 147 has KTM plastered all over it, but it’s actually not part of the Pierer Mobility Group; it’s a KTM bicycle warehouse.

The town of Mattighofen is about two hours east of Munich, Germany, and one hour north of Salzburg, which is the closest “big city.” Mattighofen feels like a small college town. Everybody knows each other, and they’re all there for the same reason. There are roughly 6700 people living in Mattighofen, and, according to local experts, roughly 5000 of those people are employed in KTM’s Mattighofen offices; however, many of them live outside Mattighofen and commute.

When the MXA wrecking crew hit town, the first place we went was to the impressive KTM Motohall. There we learned that the first KTM motorcycles were produced in 1953. Back then, the factory could only produce three bikes in a day. Today, Mattighofen’s maximum capacity is 1200 bikes a day with a yearly output of 268,000 out of a total annual production of 375,000 KTM, Husqvarna and GasGas motorcycles. The KTM Motohall gave us a history lesson that was the perfect springboard for our week-long stay. Manfred “Mandy” Edlinger, the head of motocross development, was our primary tour guide for the week. Mandy gave us an all-access pass to KTM, as he is one of the most passionate and knowledgeable guys there. Thanks to Mandy, we got to experience the Motohall, R&D building, the Factory Racing building, the WP building and KISKA offices. To top it all off, Dennis, Josh Fout and I were all able to spend a day riding at their local track on Friday. The icing on the cake was that Mandy arranged for me to race a round of the 2023 Austrian National Championship on Sunday.

I was surprised to learn that, up until the 2016 models, KTM’s engines and frames were developed at different times. You can imagine that it was counterproductive to have the two R&D crews working on different timelines. A decision by the board brought everyone onto the same page, making every new model year start by developing the chassis and engine at the same time. The 2016 models were the first bikes developed with this process, and that’s when KTM started winning 450 Supercross races with Ryan Dungey. Dennis Stapleton, Josh Fout, Trevor Nelson and I are all motorcycle geeks, so we loved learning all the details about how the engine influences the chassis and vice versa. In KTM’s eyes, this change was the key to their success. Before that, they were trying to catch up to the Japanese. From then on, they were ahead.

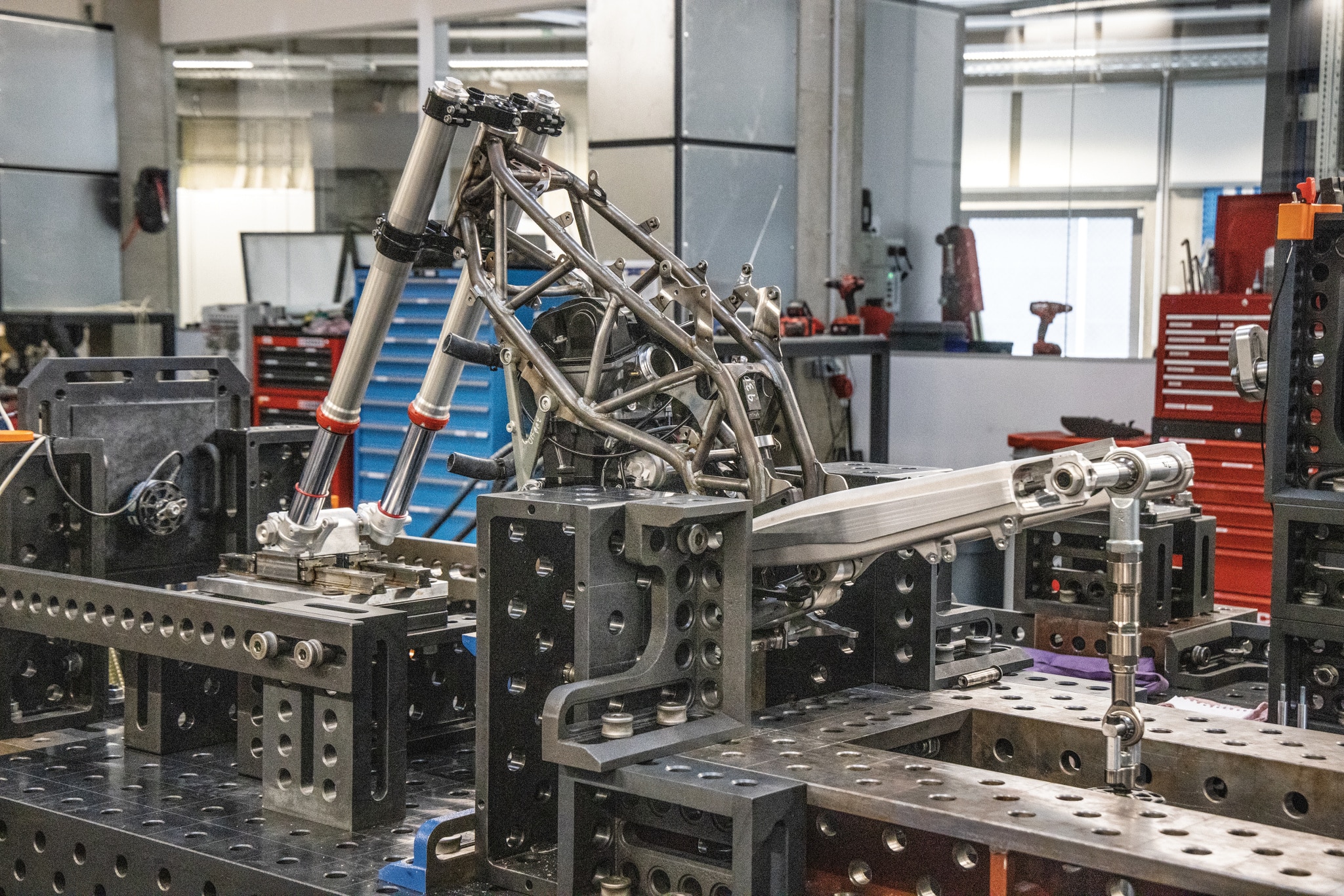

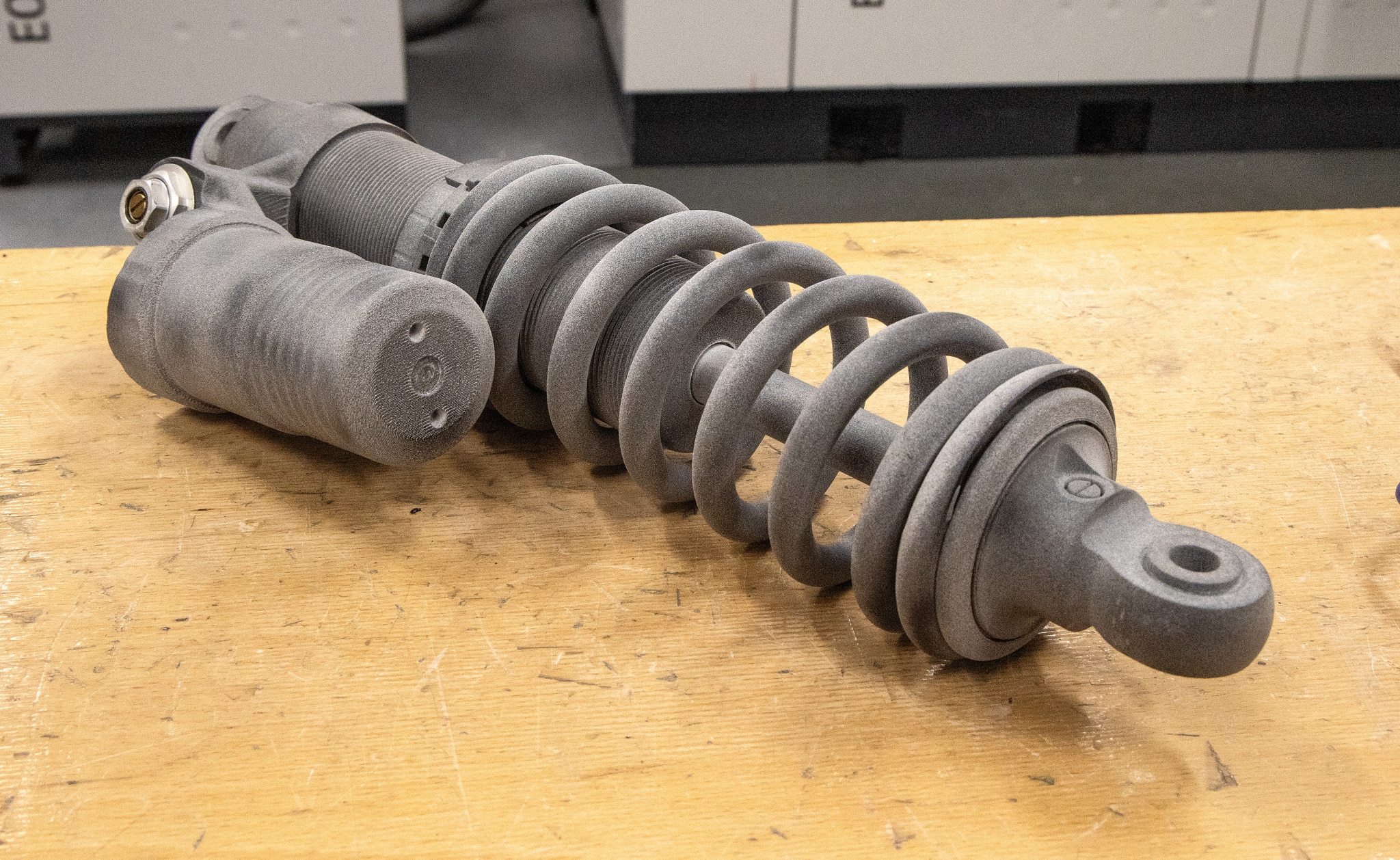

MXA is hyper-focused on motocross, so the development of KTM’s MotoGP program doesn’t regularly appear on our radar; however, it’s apparent that road racing is very important to the Pierer Mobility Group. After seeing the Moto3 bikes up close, I asked about shared technology between road racing and motocross. Of course, the Quick Shift concept comes from road racing, but what else can they transfer over? In reality, the technology used for street and dirt is very different, but it’s in the processes and systems for development where the off-road team can learn from the street team and vice versa. The MotoGP team utilizes the rapid advancements in 3D printing to fast-track parts for testing. They have 3D printers for almost every material you can think of—plastic, titanium, steel, etc. When testing a pipe, they can easily change the resonance chamber on the computer, 3D-print it overnight, put it together like a puzzle, weld it and go to the track the next day for testing. The same applies to chromoly steel tubes on the frames. KTM started working on its 2023 models back in 2018, using 3D-printed steel on the first prototypes.

The common theme for our tour of the KTM R&D facility was the “test bench.” We saw engines, chassis, forks and shocks on “test benches,” all used for gathering data to develop new bikes and to run durability tests, ensuring the products are ready for the real world. KTM has an R&D crew in the U.S., and they work closely with Mandy’s team, but Mandy and the Austrian test riders also travel regularly for testing to gather data and try their products in different environments. With sensors secured all over their bikes, they can collect data from laps at Glen Helen, the KTM Supercross test track in Murrieta and in Lommel’s sand in Holland. With the help of computers, they can replicate every bump, jump, rut and hump from Glen Helen to cycle their parts on the exact same features without flying to California. In development, each new part has to pass a three-step process. First, it has to pass the simulation test. Second, there are maximum force and durability tests, and the third leg of the process is real-world durability testing (actually riding) in the harshest conditions they can find, which is often Lommel.

WE LOVED LEARNING HOW THE ENGINE INFLUENCES THE CHASSIS AND VICE VERSA. IN KTM’S EYES, THIS CHANGE WAS THE KEY TO THEIR SUCCESS. BEFORE THAT, THEY WERE TRYING TO CATCH UP TO THE JAPANESE; FROM THEN ON, THEY WERE AHEAD.

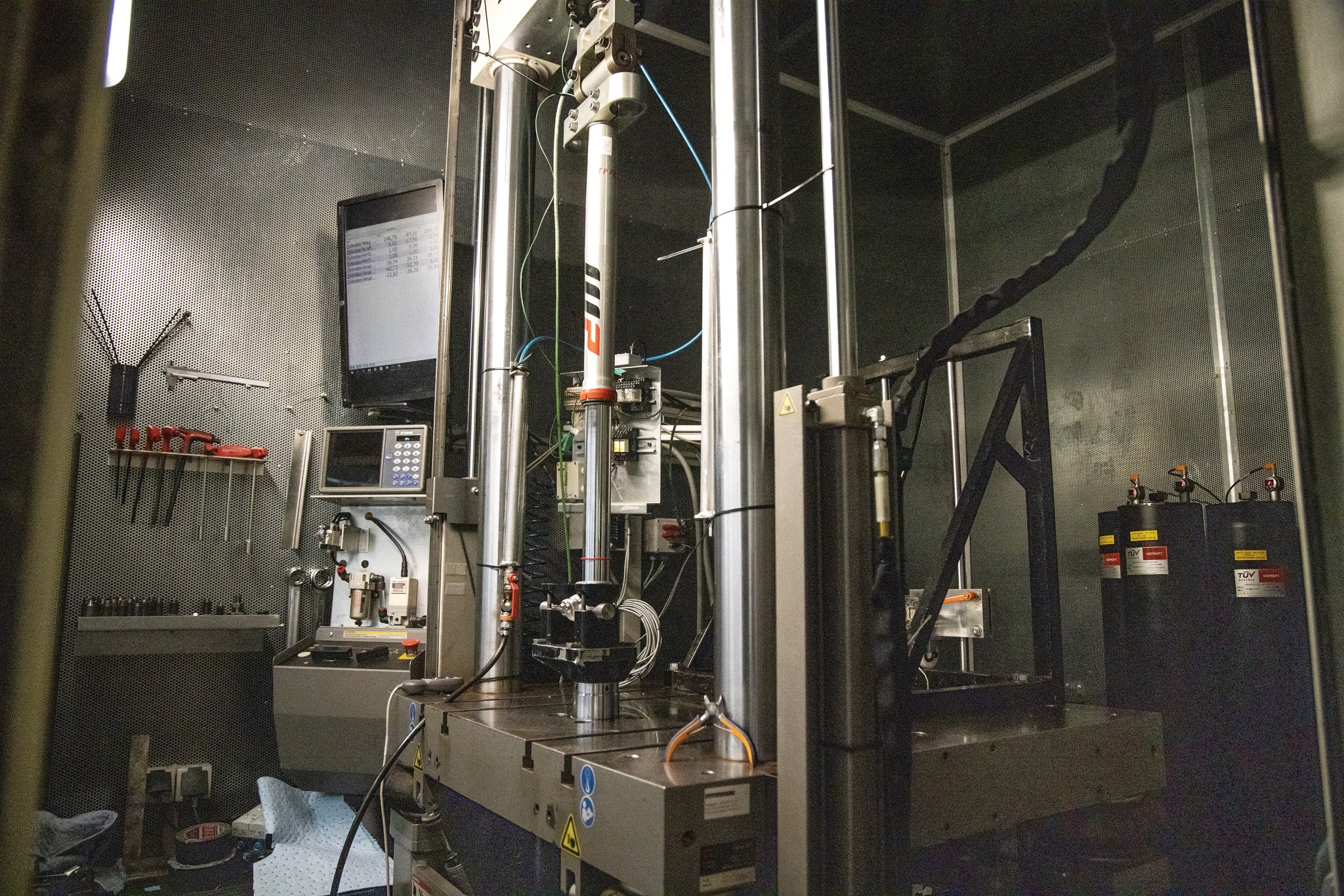

They also have a test bench to measure the center of gravity and the inertia of a bike. They strap the bike to a gyroscopic machine that holds the bike and rotates it in every direction, measuring how much force it takes to initiate movement. The machine measures front-to-rear weight bias as well. In the WP suspension R&D department, which is in a completely separate building just down the road, a fork dyno was doing durability runs with WP XACT air forks, replicating a lap of the Glen Helen track where they had a pro rider complete a full practice session at a race with sensors on his bike to collect the data. We could stand next to the fork test bench in Austria and watch the forks go up and down over every ripple on the Mount Saint Helen downhill, Triple Step-Up and Talladega first turn. In the next room, we saw a test where a machine picked up and dropped a set of forks, triple clamps and front wheel from 5 feet in the air onto the ground in a nonstop loop 50,000 times per test. Another “test bench” had the front end hitting a curb 600,000 times to test the durability of the fork’s internals.

In the engine department, there is a dedicated chief engineer for each displacement, with two mechanics working on their specific engines. They handle everything from concept to pre-production prototypes, and they help the customer service department any time there’s a problem they can’t figure out themselves. The mechanics assemble engines for testing and do quality checks on the first run of each new production engine, making sure the tolerances are all in spec. Florian Bretterebner is the head of off-road engines, and he explained that they start with milled or even 3D-printed engine cases when developing a new engine. Then, once they raise the quantity of engines, they use mostly sand-cast parts with the cylinder still being 3D-printed. The last step in development is pre-production engines made from high-pressure casting, 99 percent of which have to be made out of the stock tooling.

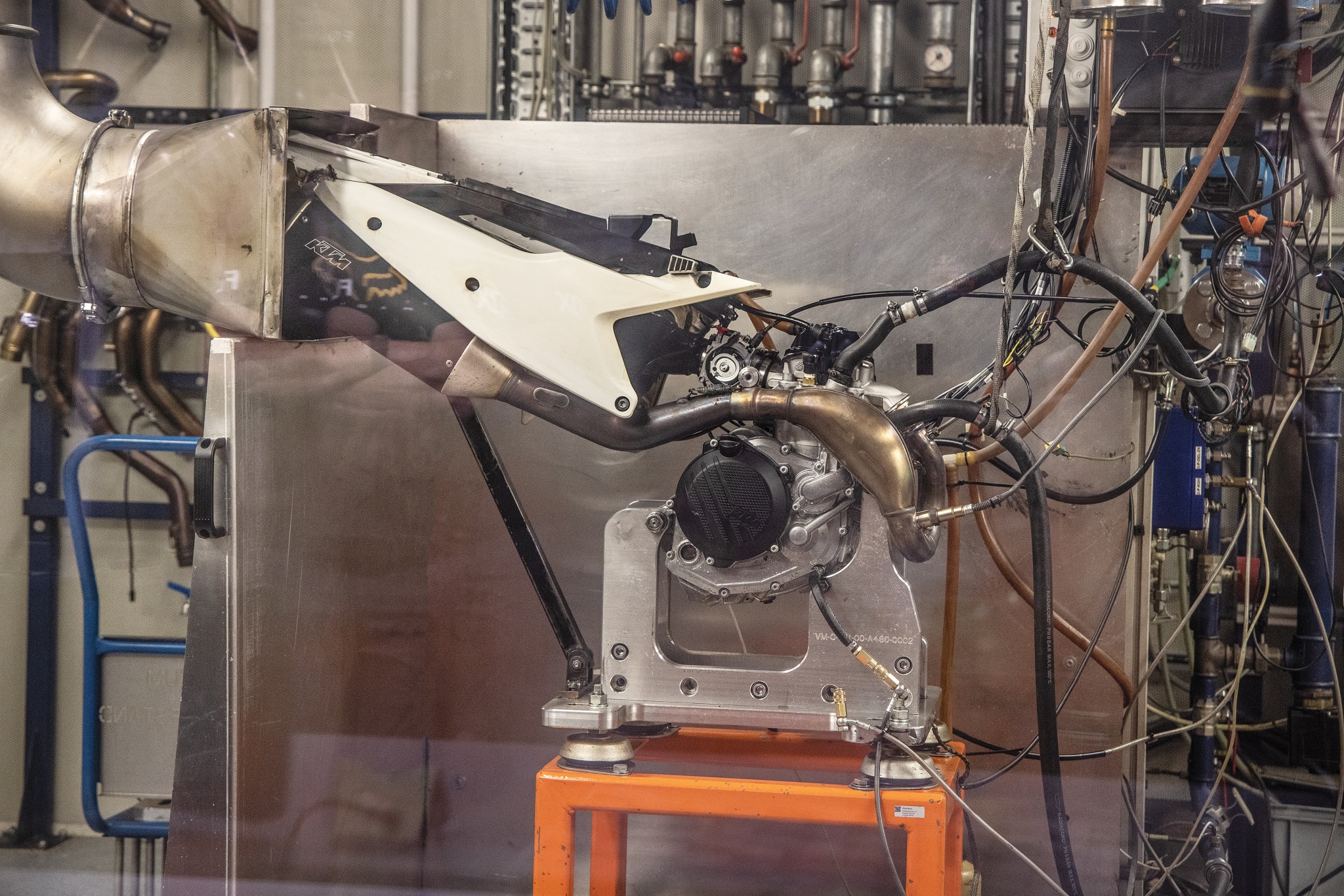

I’ve seen plenty of dynos in my day, but I’ve always been amazed by “engine dynos” where they dyno the engine by itself without a chassis. KTM has 25-engine test-bench cells, each one in a room dedicated to testing that specific model of engine. In there they have the engine with the airbox, exhaust pipe and muffler attached to it, with coolant and fuel flowing into the engine, lots of sensors attached to the ECU and engine, and a large exhaust vent for the fumes. On the engine dynos, the engines will run automatically via computer programming for up to 15 hours straight for durability testing. Of course, they have five rolling dynos, just like the one that MXA uses, but the coolest dyno of all is hidden. It’s called the “acoustical test bench,” and the room it is in looks like it belongs in a NASA outer space simulation. The room is mounted on giant springs to muffle any outside vibrations. If you’ve ever been in a recording studio with foam all over the walls to dampen noise and echoes, you will understand this room; however, instead of a drum set and electric guitar, this room has a dyno in the center of it. In this space, they can do true sound testing without input from the outside world. They can also simulate pass-by testing for street bikes with wall-mounted microphones simulating the bike riding past at the desired speed. The dyno can be repositioned within the room for different tests. They can also roll the wheels with the dyno to test how loud brake squeal is. It’s a unique experience to be in there, because without anyone talking, there’s complete silence. When someone talks, there’s absolutely no echo.

Missing from the engine department were the electric minibikes. It’s obvious that electric Pee-Wees are becoming more popular, and Stefan Pierer has talked publicly about the invasion of electric bikes into the motocross world. He’s shared that the Pierer Mobility Group will push to make more electric minibikes (like a 65 and 85) in the future, but he doesn’t foresee full-size electric motocross bikes being produced at KTM. The electric minibike development unit is now based in Salzburg, near the KISKA Design Studio.

Speaking of KISKA, you’ve probably heard this name before, most likely in the pages of MXA when we complained about bodywork mistakes, like closed-off airbox covers, the shock cover on the new Husqvarnas, or the fact that you can’t change a side number panel without removing the rear fender on the 2023 and 2024 models. However, we learned a lot about KISKA during our tour of their office in Salzburg and appreciate their efforts much more now. KISKA is the official strategic design partner for KTM. They handle the full 360-degree scope of every contact point the Pierer Mobility Group has with its customers and the public. Gerald Kiska started the design firm in 1991 with a ski-boot binding. Since then, it has grown to four different offices with a total of 270 employees from 35 different countries. KISKA has worked with Mercedes, Adidas, Kastle, Opel, Zeiss Optics, Kettler and Bosch, and they have roughly 70 active clients; however, because of Gerald’s close relationship with Stefan Pierer, the majority of KISKA’s operations are focused on the Pierer Mobility Group.

KTM has its own design goals for how the new bikes will perform, and they come up with a plan for how to get there with prototypes and testing. KISKA is in charge of how the bike looks. They come up with the design of the plastics and collaborate with KTM to make it work. Talking to the designers, they explained that their exotic designs are much easier to implement on street bikes, because ergonomics aren’t as important. Street bike riders don’t grip onto the bike as hard as motocross racers do on a track. While we were there, they were working on future prototypes for 2027 models, starting with a concept that they know is way ahead of its time, because they understand that they must shoot for the stars on the first design if they want to land on the moon with the final product. We are critical of some of KISKA’s bodywork designs for KTM, Husqvarna and GasGas, but there’s no doubt that they’ve been the market leader for design in motocross, and the Japanese have followed in their footsteps for plastic design.

KTM HAS FIVE ROLLING DYNOS, JUST LIKE THE ONE THAT MXA USES, BUT THE COOLEST DYNO OF ALL IS HIDDEN. IT’S CALLED THE “ACOUSTICAL TEST BENCH.” THE ROOM IT IS IN LOOKS LIKE IT BELONGS IN A NASA OUTER SPACE SIMULATION.

When working on new plastics, KISKA prefers to use clay modeling rather than 3D printing, because it’s even faster for making changes. Plus, with the clay models, they can have riders sit on the bike and scuff it up with their boots and knee braces to see rub points and smooth them out. They can even print graphics onto the clay to test designs. Once they’re happy, they scan the clay concept, 3D-print the plastics, and take them straight to the track. For their factory rally bike riders, they even customize the plastics and fuel tanks for their size and riding style. The best part of visiting KISKA was learning that the designers actually ride and race themselves. Maxime Lefebvre is one of the lead designers for the off-road bikes, and he is a passionate moto head whose first designs saw production in 2023. He races himself and regularly helps Mandy and the KTM R&D team develop their prototype and pre-production bikes. In addition to plastics, KISKA also helps develop the footpegs, clutch covers, start/stop switches, seats, suspension clickers and more. Off the bike, they’re in charge of the marketing program, creating advertisements, designing the websites and press releases.

The KTM factory race team is also based in Mattighofen, but I was slightly surprised to learn that the Husqvarna and GasGas factory MXGP teams don’t have a race shop there. Of course, it makes sense, because although they are factory teams, they are privately run. The Nestaan Husqvarna MXGP team is based out of Lommel, and the De Carli Red Bull GasGas factory team is Italian, but they’re based out of Lommel as well. KTM also has a shop for its practice mechanics and racers to work out of at Lommel, but the main race shop is still in Austria. We couldn’t take as many pictures inside the factory racing building, but it was fun to see the MXGP “works bikes” up close. The FIM doesn’t have the same production rule that we have at AMA races. Jeffery Herlings can race with a chromoly steel frame that’s been custom-tailored to him. Talking to the R&D crew at KTM, they actually prefer the AMA’s production rule because it creates a closer relationship between R&D and factory racing. With the MXGP teams, the bikes can be wildly different from stock, with each rider having the ability to completely customize his bike.

Factory Racing has its own engine department, and its mechanics build around 700 engines a year. Like R&D, they also have dedicated engine builders for each engine displacement. One random but interesting find was a vending machine with everyday supplies like rubber gloves, tape, glue, lube, Loctite, rags and Scotch-Brite pads in it. Of course, the mechanics don’t pay to get their supplies, but the machine keeps track of inventory to ensure they never run out of essential supplies. Pretty cool, right?

I know MXA’s future KTM/Husqvarna/GasGas articles will be better because of the things we learned during our seven days in Mattighofen. Experiencing the factory up close and personal was amazing, but our tour didn’t end there. We went with the KTM R&D crew for a day of practice at the X Bowl Arena track on Friday, and we joined them for a full-on race weekend at an Austrian 450 National at Mehrnbach, which was the natural conclusion to our time in Austria.

Almost every key employee that we met while at the KTM factory, we also spent time with at the race. They were either racing themselves, or they were there working at the event. I can truly say that I found the key to KTM’s success while racing at the Mehrnbach National. It is because KTM is manned by passionate employees who race themselves. And, based on the number of engineers we saw racing with their kids, it doesn’t seem like they’ll stop any time soon.

Comments are closed.