WHEN GIANTS ROAMED THE EARTH & IRON MEN RODE THEM

By Terry Good and Tom White

When Edison Dye and Torsten Hallman first introduced motocross to the U.S. in 1966, one of the most interesting and important eras in motocross history had already come and gone. Since the sport was so young in the United States, very few teenage Americans ever heard of the Monark/Lito/Husqvarna four-stroke era. Considered the golden era of motocross, it only lasted from 1957 to 1965.

After having suffered through two World Wars, economic depression and tyranny, Europe was rebuilding at an exponential rate through the 1950s and 1960s. Motocross was growing in popularity all across Western Europe and was quickly becoming one of the premier sports of the working class. To capitalize on this growth, a World Motocross Championship was established in 1957, and crowds as big as 100,000 spectators came to watch the Iron Men of Motocross muscle their giant 500cc four-strokes. Motocross was a big deal.

To win the World Championship was a major accomplishment, and motorcycle manufacturers like Belgium’s FN and Sarolea; Britain’s Norton, BSA, Rickman, AJS and Matchless; and Sweden’s Monark, Lito and Husqvarna designed and built very expensive handmade works machines in their quest for the championship.

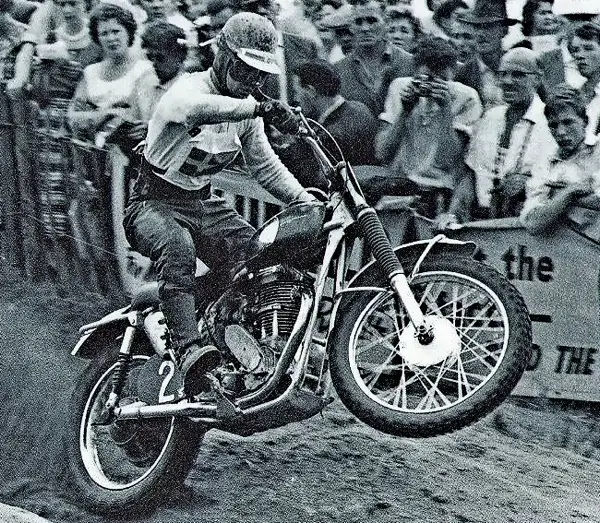

The riders of this era were household names among the fans. To ride these giant Grand Prix bikes (often exceeding 300 pounds) at competitive speeds, you had to be almost superhuman. Les Archer, Jeff Smith, Brian Stonebridge, Auguste Mingels, John Draper, Rolf Tibblin, Gunnar Johansson, Rene Baeton, John Avery, Victor Leloup, Bill Nilsson and Sten Lundin were just such human beings.

THE BIKES THEY RACED WERE NEVER INTENDED TO BE SOLD TO THE PUBLIC. THEY WERE THE FIRST TRUE WORKS BIKES, AND ONLY A HANDFUL WERE EVER BUILT

The bikes these men raced were never intended to be sold to the public. They were the first true “works bikes,” and only a handful were ever built. The surviving bikes from this 1957 to 1965 era are among the rarest and most expensive motocross bikes on the planet. Highly coveted by collectors and in extremely short supply, these machines can easily fetch $100,000 on the open market. Amazingly, there is even a cottage-industry that builds copies of the originals (and the replicas can sell for astronomical amounts — upwards of $50,000 — for a fake).

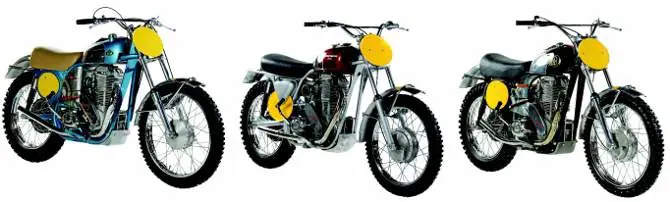

MXA wants to introduce modern American motocross racers to the three most important motocross bikes ever made. These handmade, one-off works bikes ushered in the modern motocross era. They were the harbinger of factory teams, professional riders, corporate competition and works machinery. These booming, 500cc, single-cylinder, four-stroke giants roamed the earth for less than 10 years, and they never numbered more than 50, but they left an enduring legacy. Travel back 50 years to meet the Monark 500, the Lito 500 and the Husqvarna 500.

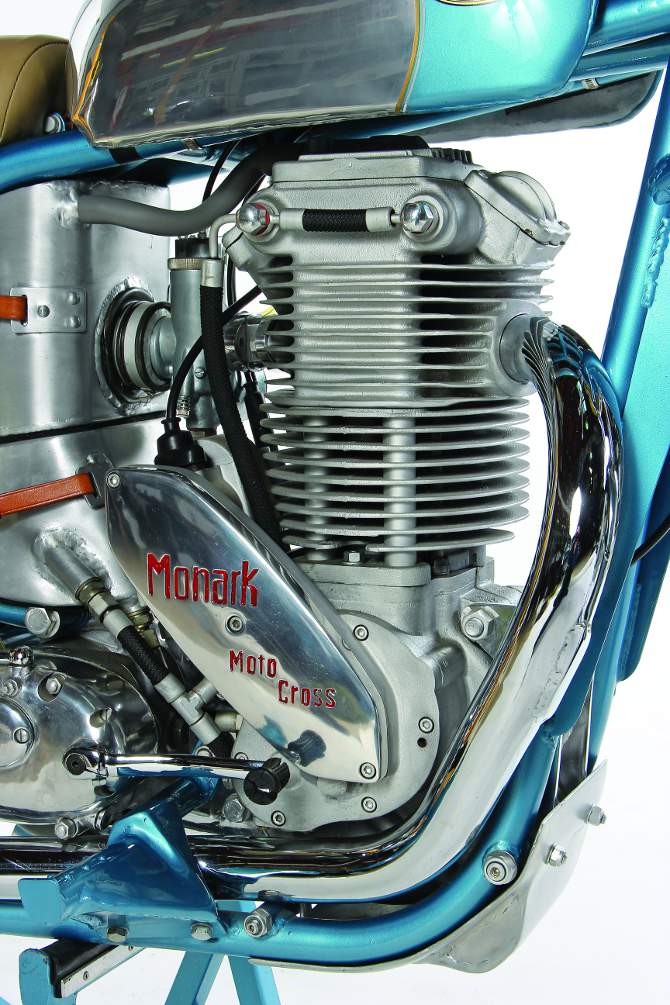

1960 MONARK 500 (1957-1960)

The Albin-powered Monark has the most varied history of any motocross bike ever made. It was an incredible machine and spawned its own competition. Monark was the first Swedish manufacturer to get involved in Grand Prix motocross, starting in the late 1950s. They built a total of five GP Monark works bikes from 1957 to 1960. As each of these bikes was used and abused, the parts from the original bikes were taken and used on the newer bikes. Each bike was individually designed by Monark; no two bikes were the same. Years after the factory shut down in 1960, a couple bikes were built from leftover parts. No bikes were ever sold to the public, and all that survived are accounted for today. There will never be a barn find of a Monark 500.

Only five Monark 500s were made. They sell for $100,000 apiece on the vintage bike market.

Sten Lundin’s 1960 Monark GP bike was built during the winter of 1959. The entire bike was made by hand by a handful of Monark engineers at the Monark factory in Varberg, Sweden. The facility was state of the art, and Monark had the resources to build the finest bike that anyone could conceive. Detailed scale drawings were made and extensive testing was done by Sten at a special track near the Varberg plant. The bike was very sleek, well balanced and parts were made from the highest-quality materials available. The swingarm, for example, was made from special, thin-wall, conical tubing to save weight. The rear brake rod was converted to a cable for reliability, so if any rider bumped it during a race, it would not bend. Even the chain adjusters received special attention. The attention to design and construction were amazing, and the final weight was 282 pounds.

This was the 1960 version of a motocross star — Sten Lundin. Photo: Sten Lundin Archive

The powerplant was the 498cc Albin engine originally developed for the Swedish army in 1942 (based on a design from 1935). The Albin engine was simple, reliable and very slim. It also allowed for tremendous performance potential. Behind the scenes at Albin was Nils-Olov (“Nisse”) Hedlund, a master engine builder and former road racer, whose influence on four-stroke engine design would later culminate in his own production 500cc racing engine.

On a strange historical note, the Swedish motocross industry owes a debt of gratitude to the 1956 Suez Canal crisis. When Great Britain was put on gas rationing because of the Suez Canal closing, BSA decided to pull out of European racing. With no BSA support in 1956 and 1957, a group of Swedish motocrossers decided that they could not rely on BSA any more and started to look for a homegrown product. The Swedish-built Albin engine was chosen, and an exhaustive effort was made — largely by Nisse Hedlund (working for Endfors & Sons) to de-stroke the old Albin engine and open up the bore to produce more horsepower (approximately 27 horsepower) with a very linear and torquey powerband. Not as fast as the Belgian FN engines, but with a much more controllable powerband, the Albin was a good Swedish engine for a Swedish bike. Hedlund would become a major player in the success of Monark, Lito and Husqvarna.

When Sten Lundin switched from Monark to Lito, he kept on racing his original Monark in Lito paint.

Monark was the first motorcycle manufacturer to chrome-plate the cylinder bore (this could only be done in Germany at the time). Different frames were tried, but Sten Lundin settled on the original design. If there was anything that wasn’t quite right, changes were made very quickly at the factory. It was also like this during the season. For example, the original BSA gearbox was changed to an AMC gearbox. There was a lot of vibration from the engine, and after a while, Sten’s hands would go numb. The factory solved this with the first-ever head stays that went from the frame to the valve covers.

This Monark drum brake was inadequate for stopping a 280-pound race bike, but was state of the art for the era.

Another time, the front forks broke during practice at an international race in Italy. Sten made a makeshift repair and still won the race. A local guy who was working at MV Augusta had seen the trouble Sten was having and offered to help. He told him that his grandfather owned a factory where they manufactured front forks. The young man invited Sten to the factory to meet his grandfather, Arturo Ceriani. Ceriani made Sten a special set of handmade forks. This was actually the first set of Ceriani front forks ever made for motocross. Also, the prestigious MV road racing factory took Sten’s bike and gusseted the front downtubes for strength. When performing this mod, the MV Agusta race team was so concerned about any of their race-shop equipment being seen that they would not allow Sten in the shop while the modification was being performed.

The Albin engine was a basic powerplant until worked on by Nisse Hedlund.

During the 1960 season, Monark race team manager Lennart Varborn unexpectedly died. As a result, Monark withdrew from Grand Prix racing. That may seem odd in today’s high-powered corporate environment where a team would just replace the manager and move forward, but it was originally Lennart’s decision for Monark to be involved in Grand Prix motocross racing. After his death, management decided not to replace him. This was a huge blow to all those involved with the Monark team, as they had worked very hard, had a winning combination, and it seemed their best years lay ahead. As a consolation, the Monark factory gave Sten Lundin his GP bike, but the sponsorship was over.

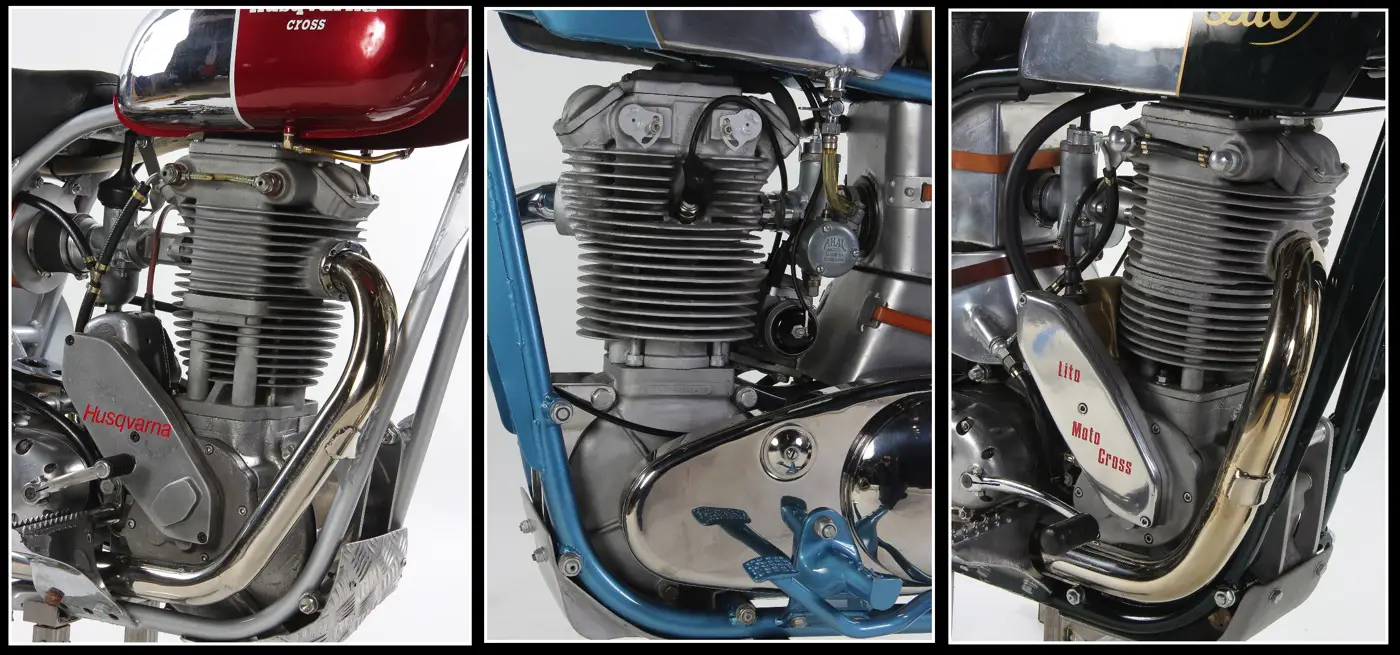

The Monark, Lito and Husqvarna were all fueled by Amal carburetors.

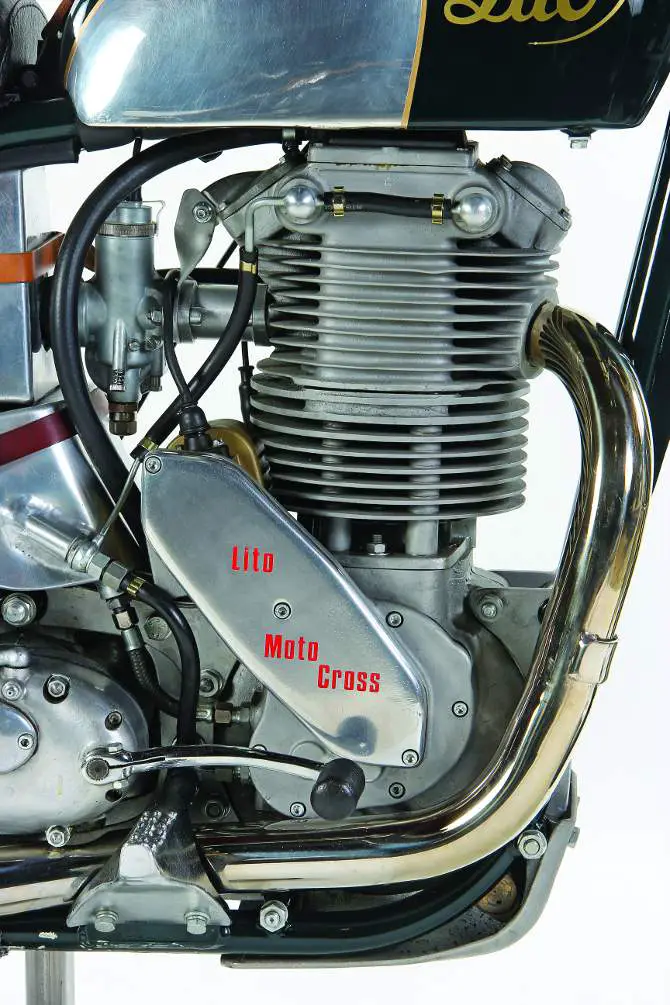

LITO 500 (1961-1964)

When the Monark team was shut down, another member of the Monark empire, Kaj Bornebusch, saw an opportunity to pick up where Monark had left off by building motocross bikes for non-factory riders so they could compete on the same level as the factory teams from Belgium and England. Kaj had competed in British Scrambles races while he was going to college in England. He named his new bike the Lito (after a company he owned that specialized in lithographs). The Litos would share many of the components of the works Monark, most notably the Albin engine. The Lito was a first-rate bike.

Just like Monark before them, Lito only made a handful of race bikes over its four-year life span.

Sten Lundin, now the sole owner of a works Monark, went to Kaj Bornebusch and made the proposal that if Lito sponsored him, he would paint his Monark green and race it with Lito logos. Kaj agreed. And on February 10, 1961, Sten Lundin signed a contract with Lito. His Monark was painted green in 1961 and became (in name only) a Lito. Lundin won the 1961 World Championship, took third in 1962, second in 1963 and third in 1964. He also won the overall at the Motocross des Nations in 1963 on his hybrid Lito.

The care taken in building the Lito is evident in the detail of the chain adjuster, rear brake arm and shock mount.

When the Litos went into production, only 35 machines were built between 1961 and 1965. The Litos were beautiful bikes with all the right components to be competitive in Grand Prix motocross. Sten Lundin did have one Lito-built machine, which he used in local Swedish motocross races, but for the 500 GPs, he raced his 1960 Monark (painted in Lito colors).

Monarks and Litos raced way before the development of long travel suspension, gas shocks, remote reservoirs or piggyback shocks.

The Litos were built on a made-to-order basis, and many of the top riders of the day used them, including 1957 and 1960 World Champion Bill Nilsson, Sylvain Geboers and Gunnar Johansson. The remaining stock of the 35 bikes went to privateer GP riders all over Europe. It was a works bike for the average guy.

Not surprisingly, since the Lito rose from the ashes of the Monark race team, the two bikes shared many parts, not the least of which was the Swedish-built Albin engine.

Today, many of these original Litos remain in collectors’ hands. There is even a registry for all the known remaining bikes. In the early 1990s, a group of Swedish enthusiasts built several replicas that are very close to the real thing. These bikes have a different serial-number sequence and are also very collectible.

Sten Lundin won the 1961 500 World Championship on his Monark/Lito hybrid.

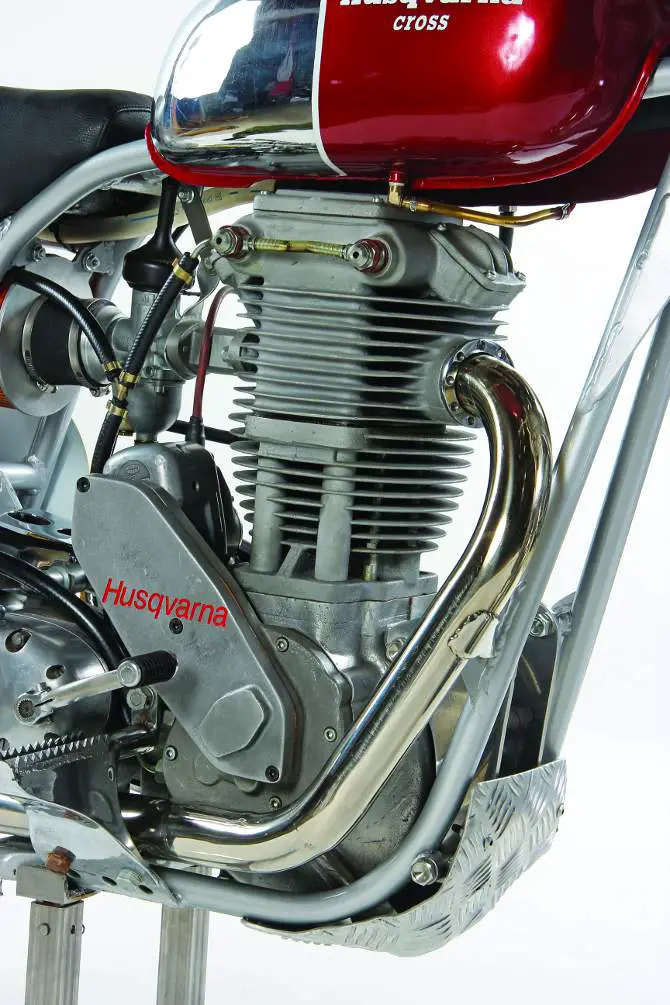

1960 HUSQVARNA ALBIN 500

Husqvarna, like Monark, was a very old company in Sweden that produced many things, including street and road race motorcycles. After having witnessed the huge success and publicity that Monark was getting from their motocross endeavor, Husky decided to enter the 500 World Championship for the 1960 season. They had a “start from scratch” works bike program, but with a much lower budget than Monark.

Before 1960, Husqvarna made large displacement four-stroke street bikes and road racers, but they became jealous of the publicity that Monark was getting in motocross and joined the fray.

The program was headed up by Ruben Helmin, and the bikes would be assembled by Morgan Hjalmarsson at the Husqvarna factory. Husqvarna designed their bike around the same basic powerplant as Monark — the ever reliable Albin 500 single. The front forks were Norton Roadholders from England, and the rear shocks were Girlings.

1960 500 World Champion Bill Nilsson.

Although Sten Lundin preferred Ceriani forks, the Huskys of Bill Nilsson and Rolf Tibblin used Norton Roadholder forks.

In a brilliant move, Husqvarna commissioned Nisse Hedlund, who had built a reputation with the Albin single, to build their engines. The 1957 World Champion Bill Nilsson was hired to ride the bike, along with Rolf Tibblin. Two bikes were built, with Nilsson getting the preferred support. In their debut 500 GP season, Nilsson and his 500cc Husqvarna four-stroke won the 1960 500cc World Championship, defeating Sten Lundin and his Monark by one point. Rolf Tibblin took a respectable third. Only three works Husqvarna Albin 500s were made, and none were sold to the public.

Husqvarna didn’t just use Hedlund-modified Albins; they also hired the young designer to ramrod the bikes through production.

HEDLUND HUSQVARNA 500 (1961-1962)

No leather straps for the Husqvarna, they built a metal strap that could double as a surgical scalpel in a crash.

The success Husqvarna had with Nilsson and Tibblin in 1960 prompted many requests for Grand Prix Huskys. Like Monark, Husqvarna had no intention of mass-producing such a machine. But, engine builder Nisse Hedlund had the same vision that Kaj Bornebush had when he started Lito, and Hedlund, with Husqvarna’s blessing, produced 16 replicas of Bill Nilsson’s 1960 World Championship bike for the 1961 season. Nisse Hedlund built the frames and engines himself and purchased the rest of the components. Like the Litos, these bikes were only sold to promising GP riders. Ten bikes were made in 1961, and six were made in 1962. Out of these 16 bikes, only three remain 50 years later.

THE GIANTS BECOME EXTINCT

These three works bikes — the Monark, Lito and Husqvarna — came and went in the blink of an eye. By 1965, the writing was on the wall, and it was written in two-stroke premix. By 1966, if you didn’t have a two-stroke, you didn’t win. The era of the booming singles was over — not to return for 40 years. Most of these unbelievable bikes were sold cheap once they became obsolete. Some were dismembered for their parts, and some were left to rot. So few examples remained that the sport owes a debt of gratitude to the men who preserved them. Whatever their reasons for holding on to these pieces of classic iron, they did all of us a huge favor by preserving an important part of the golden era of motocross. In MXA’s case, the late Tom White’s “Early Years of Motocross Museum” had one of each that we could photograph.

Comments are closed.