MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE GRANT LANGSTON’S AND RYAN HUGHES’ 2003 KTM 125SXs

By Tim Olson

Editor’s note: We sometimes get misty-eyed thinking about past bikes we loved, as well as ones that should remain forgotten. We decided to take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and forgotten in the MXA archives. We love reminiscing over a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our 2003 test of Grant Langston’s versus Ryan Hughes’ 2003 KTM 125SXs.

The final round of the 2003 125 National Motocross Championship at Troy, Ohio, could have been an epic battle that would have gone down in the annals of motocross. It didn’t happen. Fate, in the form of a massive rainstorm, stepped in and dealt a cruel blow to both riders. How could it have been cruel to both? Easily. While Grant Langston was happy to be handed the 125 motocross title on a technicality, he understood that his title would forever be marked by an asterisk. Hughes, on the other hand, had raced through pain and doubt to gain points lost when he broke his leg mid-season. The flooding in Ohio, and subsequent cancellation of the final round, left him feeling cheated.

THE FINAL RACE THAT NEVER WAS

I felt equally cheated, but unlike Grant and Ryan, I didn’t have to let it end like this. I could stage the final motocross showdown by myself. I didn’t need the AMA or a break in the weather. Shucks, I didn’t even need Grant or Ryno. Instead, I would take both of their factory KTM 125SXs, prepped for Troy, Ohio, but never used, and run my own 125 National motocross Championship final. It would be me versus me. Or, if you prefer, Grant Langston’s KTM 125SX versus Ryan Hughes’ KTM 125SX, with me playing both riders—minus the Boer accent.

FATE, IN THE FORM OF A MASSIVE RAINSTORM, STOPPED LANGSTON AND HUGHES FROM FIGHTING OUT THE 2003 125 CHAMPIONSHIP.

SO WE DID IT FOR THEM.

This was a banner year for KTM. The Austrians had never won an AMA National Motocross Championship before. In fact, they hadn’t even won a National until Budds Creek in 2000 (when Kelly Smith won in the mud). Grant Langston got KTM its first 125 Supercross victory and almost won the 125 National Championship in 2001, but he lost it at the final round at Steel City to Mike Brown when Langston’s rear wheel came apart.

THE BIKES ROLL OUT OF THE TRUCK

You may think it is stupid to test two KTM 125s against each other. After all, how different could they be? Surprisingly, it only took two seconds to realize that Langston and Hughes have completely different KTM 125s. Apart from the orange plastic and graphics, there are few similarities.

RATHER THAN A SINGLE-ENGINE SPEC FOR THE TEAM, KTM’S IN-HOUSE ENGINE TECH PROGRAM LISTENS TO THE DEMANDS OF ITS RIDERS AND BUILDS SPECIALIZED POWERBANDS FOR EACH.

What are the visible differences? (1) Langston runs Renthal Fatbars with Tag Metal grips. Hughes runs Renthal TwinWalls with Renthal soft-compound full-waffle grips. (2) Langston runs his bars low. Hughes runs his bars in the traditional position. (3) Langston runs his levers up. Hughes runs his levers slightly lower than level. (4) Langston runs KTM works footpegs. Hughes runs exceptionally humongous Fro footpegs. (5) Langston runs a Doma pipe and silencer. Hughes runs an FMF pipe and silencer.

And those are just the differences on the outside.

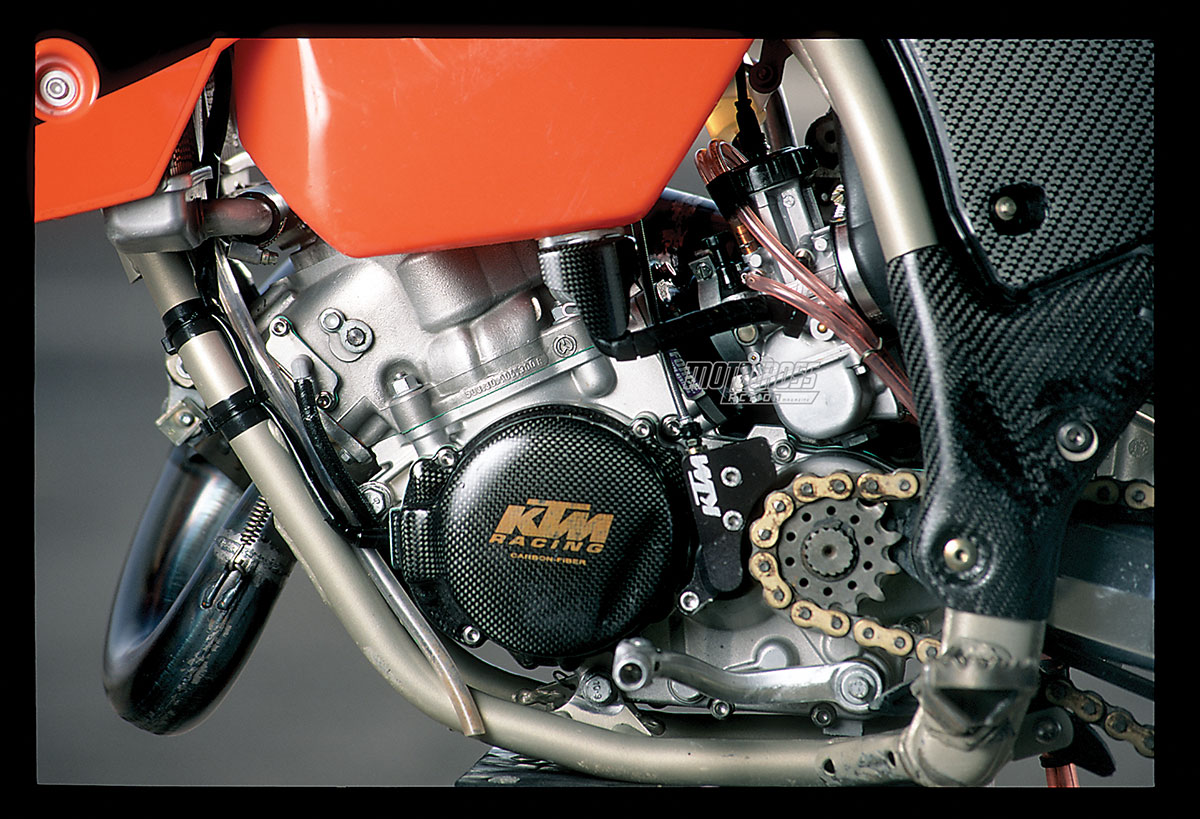

THE ENGINES OF THE KTM STARS

KTM has the most aggressive 125 engine program in the sport. The factory has not given up on two-strokes or handed the R&D over to a small team of back-room workers. It is an upfront project with massive management support. They want to build the best 125cc engine imaginable—and it shows.

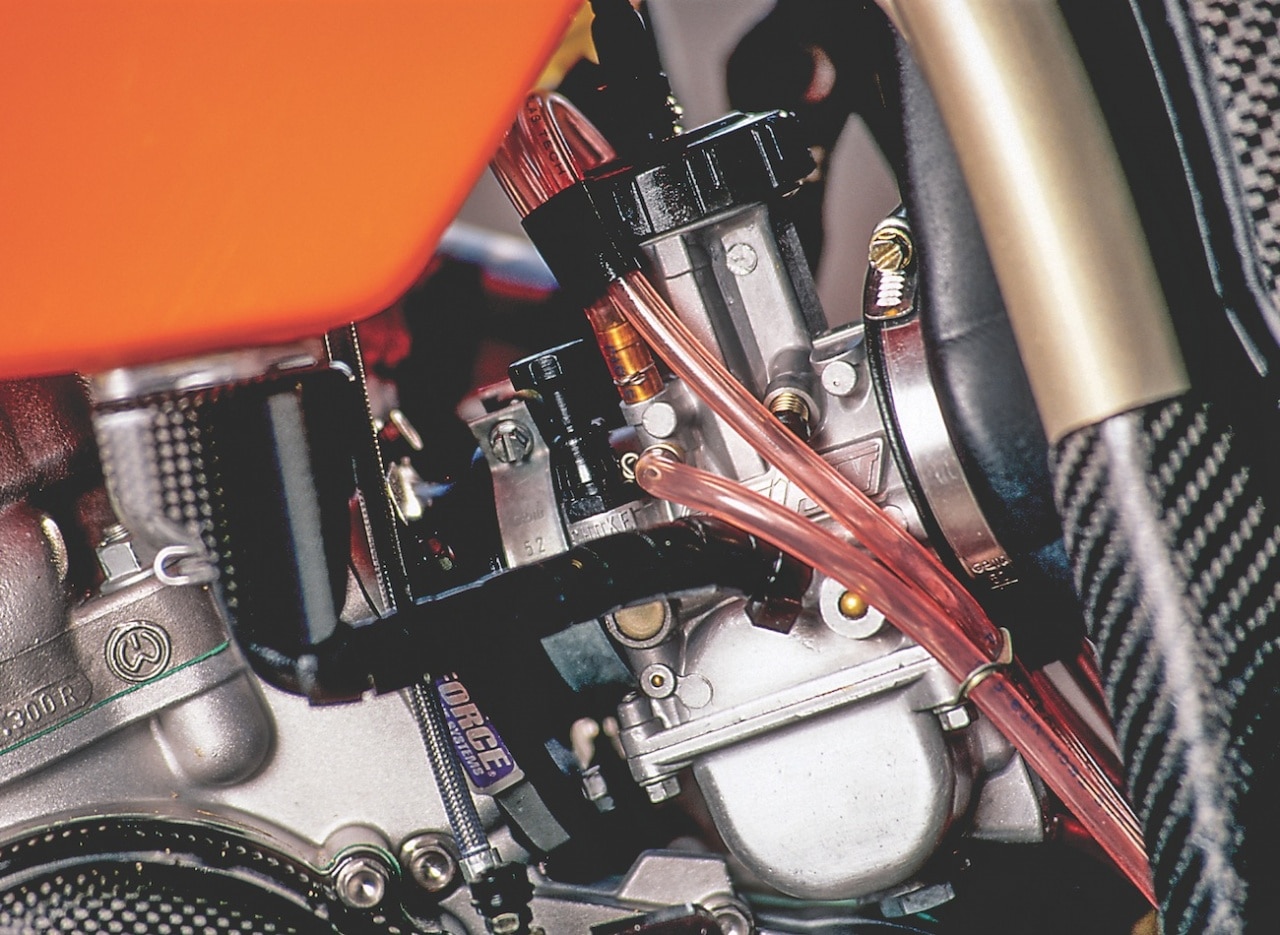

Rather than a single-engine spec for the team, KTM’s in-house engine tech program listens to the demands of its riders and builds specialized powerbands for each. What does that mean? Langston’s engine has completely different power characteristics from Hughes’ engine. The only thing they both share is a very impressive 40 horsepower on the dyno.

Langston’s powerband: I rode Grant Langston’s 125 National Championship-winning machine first. It’s a strange feeling to roll out on a track with another rider’s bike, number and decals, but it is by no means a bad thing. I was on cloud nine. The only other person to have ever ridden this bike was Grant—and when I kicked it to life, it was the first time the engine had run since it had been shut off at Steel City.

GRANT LANGSTON REALIZES THAT SUSPENSION IS SUPPOSED TO GO UP

AND DOWN. HE’S NOT PART OF THE RIGID BRIGADE.

Langston’s bike pulls your arms back the instant you jiggle the throttle. It continues to pull through the middle and on into the top. It is powerful. The KTM cracks 40 horsepower with ease, while most of the 125 field is lucky to get close to 39. What amazed me even more than the power, though, was how easy it was to ride. Even a 125 Beginner would have loved Langston’s powerband. It was, in a word, broad. It didn’t fall off the pipe, huff, puff or bog. All I had to do was shift up and go. It would always pull the next gear, no matter how ham-footed my technique.

Hughes’ powerband: If Langston’s key word was “broad,” then “hit” was a one-word description of Ryno’s power delivery. Unlike Langston’s 125SX, which pulled from the crack of the throttle, Ryno’s powerband skipped the bottom end and jumped right into the midrange. I couldn’t lug Ryno’s engine around like I could Grant’s. Instead, I slammed it into the corners, flicked the clutch and contorted my right wrist. Ryan’s bike wasn’t as easy to ride as Langston’s, but the excitement factor was off the charts. The midrange hit like a sledgehammer, and the top-end never wanted to end. Rather than upshifting early, as with Langston’s bike, I wrung Ryno’s engine out until dogs howled in the next county. Then, and only then, did I shift.

THE SUSPENSION OF THE ORANGE DUO

You shouldn’t be surprised to discover that two guys who have such different taste in powerbands also disagree on suspension setup.

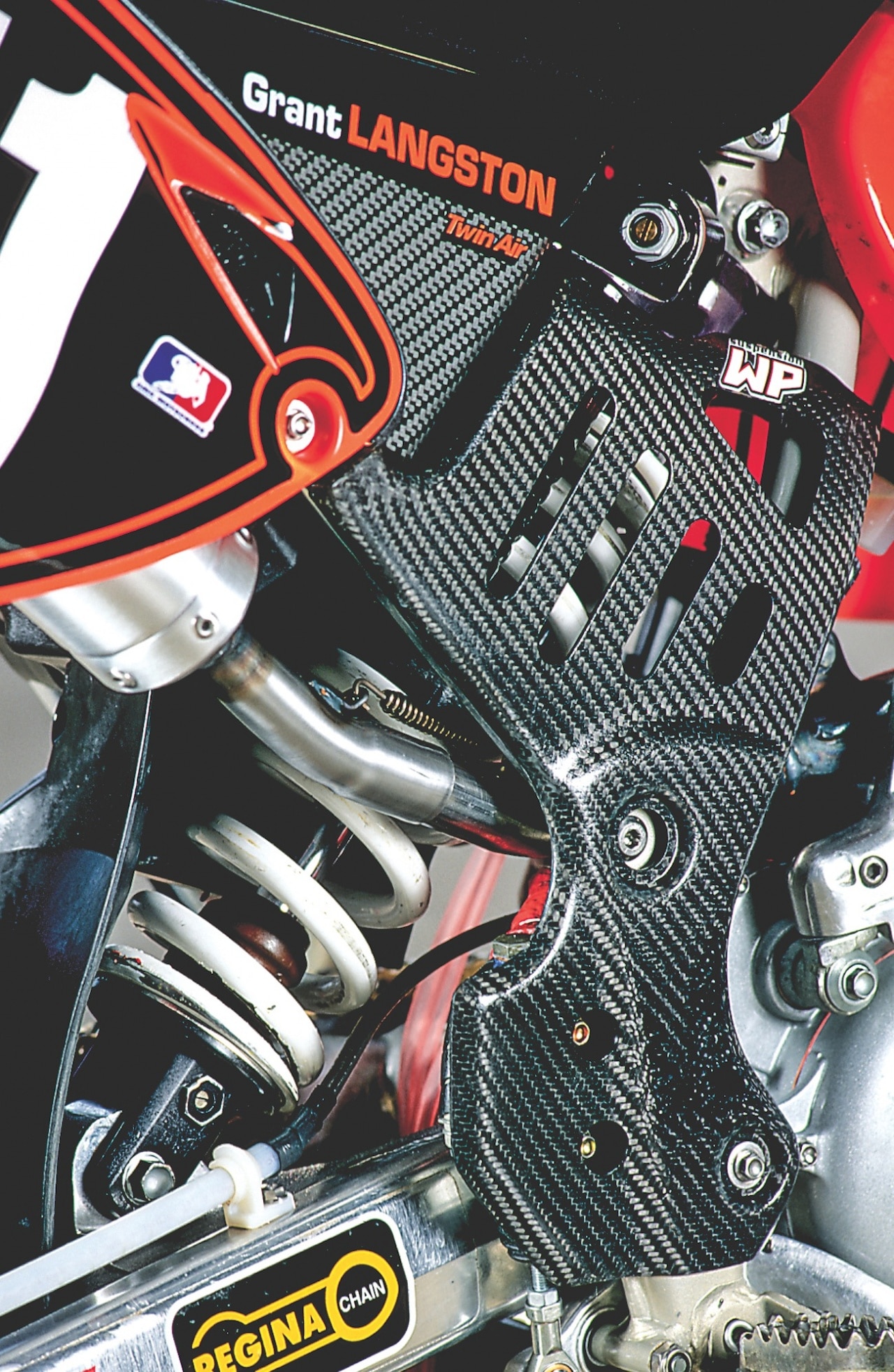

Langston’s suspension: I have to personally commend Grant Langston’s ability to select damping and spring rates. Unlike most factory riders, Grant realizes that suspension is supposed to go up and down. He’s not a part of the rigid brigade. Unfortunately, his exceptionally soft suspension settings are often the brunt of a few jokes around the KTM pits. They shouldn’t be. In my opinion, it is a lot easier to go fast on a bike that absorbs bumps than one that deflects off of them. Grant’s suspension is soft, but not to the point of bottoming. Instead, the suspension devours every small, medium and large bump (and still has room for extra large).

IF YOU ARE FAST ENOUGH, RYAN HUGHES’ SUSPENSION WORKS GREAT.

IF NOT, IT WILL BRUTALIZE YOU.

Hughes’ suspension: On the other hand, Ryan’s suspension was anything but soft. Oh, don’t get me wrong, it is very typical of the modern Pro setup. It stays high in the stroke, gets progressively stiffer through the mid-stroke and resists bottoming at all costs. If you are fast enough and, more important, in good-enough shape, Ryan’s suspension works great. It is predictable, doesn’t bottom and keeps the chassis from making radical geometry changes. If, however, you are not fast or strong enough to push the suspension into its envelope, it will brutalize you. At slow speeds, I felt every jolt through the bars and into my forearms. Ryan Hughes is a man who can handle this kind of suspension. I’m not.

RIDING THE MEN’S MACHINERY

In back-to-back tests, the sensations, vibes and effectiveness of both bikes were startling. The two bikes were so different, yet the two riders dueled each other to a standstill. It was obvious that these riders have different needs and these requirements are met by bikes that cater to their particular fancies. The question for me, and for me alone, was, which one could I have won my fantasy 125 National Championship showdown with?

For the first 10 minutes of a long moto, I was faster on Ryan Hughes’ machine. I loved the midrange hit, the rev-ability and the fact that I was dangling on the thin edge of the curve. But, as my test motos wore on to the halfway point, I suddenly started to go faster on Langston’s bike (or did Ryan’s all-or-nothing engine and suspension simply wear me out?). When I was fresh, I could get away with Ryan’s narrower powerband and stiffer suspension, but when push came to shove, Grant’s broader powerband, larger margin of error and plush suspension covered up my mistakes.

WHAT DO I REALLY THINK?

For me, Grant Langston’s bike did a lot of the work, while Ryan Hughes’ bike forced me to work harder. Which one would I pick? If I were in the same physical condition as Ryan Hughes, I’d choose his bike. I was much more comfortable with Hughes’ bars, grips, footpegs, riding position and engine characteristics. But, I’m not as fit as Ryno. Thus, my personal limitations demand Langston’s more forgiving setup.

Comments are closed.