RYAN HUGHES RETROSPECTIVE: HE LEFT IT ALL ON THE TRACK

By Eric Johnson

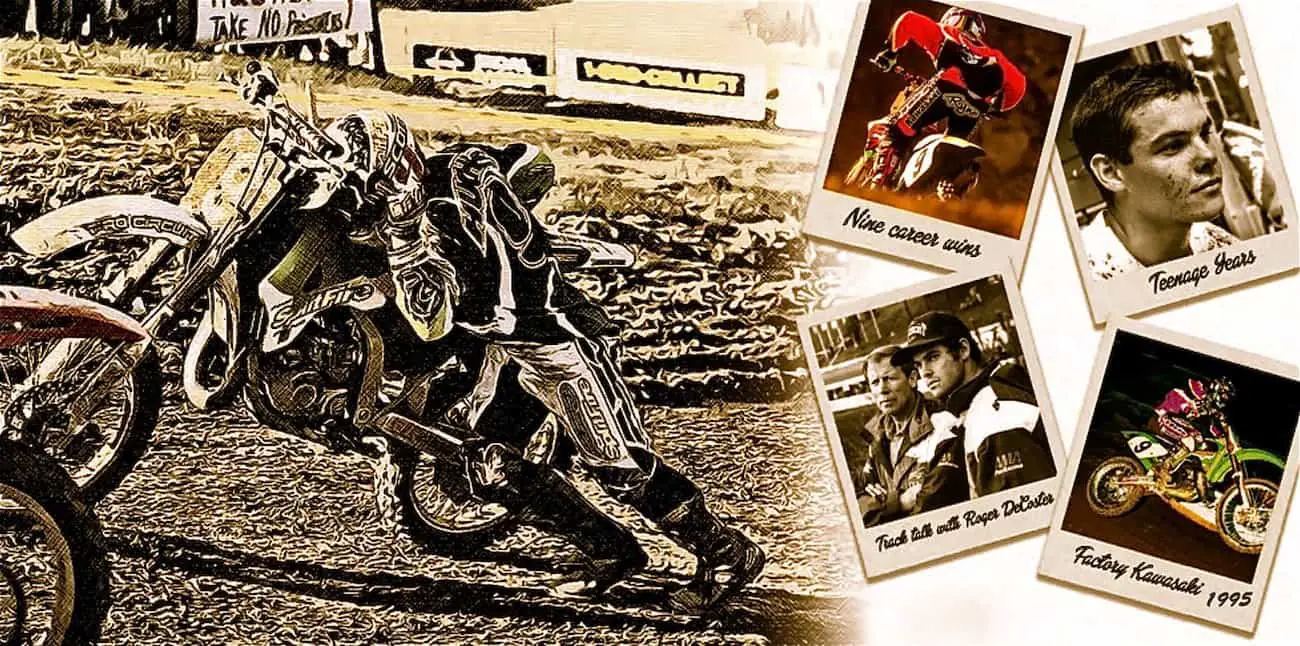

Driven both on and off the track by a desire to be the very best he could be, Ryan Hughes’ sheer guts still resonates with motocross fans the world over. With a gritty style of racing and a never-say-die attitude, Hughes threw down absolutely everything he had to get to the front. Sometimes he got there, sometimes he didn’t, but no one in the stands ever left the races without knowing that the man they called “Ryno” had left it all out on the track.

Ryan Hughes grew up in Escondido, California, a town of 140,000 inhabitants nestled in San Diego’s North County region and located some 30 miles northeast of downtown San Diego. His father Bill Hughes and brother got Ryan into riding and racing in the mid-1980s, a form of recreation he was initially very reluctant to participate in.

“For some reason I was always too scared to race,” said Hughes, who at age 11, hadn’t quite embarked on what would become a 30-year odyssey. “I was playing football at the time, and in my mind I was going to be a professional football player. When they finally got me out to the track one day, I wouldn’t get out of the truck. I was crying, ‘No, Dad! I don’t want to go, Dad! No! No!’ He finally got me out on the track. While I was riding, I fell down and some guy on a big bike stopped and helped get me going. In my mind, that was it. Click! ‘Wow! These guys are nice!’”

“MITCH WOULD CALL ME AT THE END OF THE DAY AND SAY, ‘HOW WAS IT?’ I’D SAY, ‘GOOD. I DID TWO 40-MINUTE MOTOS, WENT RUNNING AND THEN WENT CYCLING.’ MITCH WOULD SAY, ‘GOOD. MAYBE YOU SHOULD GO RUNNING AGAIN.’ SO, I WOULD!”

Ryan (far right) with Kawasaki team manager Roy Turner, Mickael Pichon and Mitch Payton (far left).

Ryan (far right) with Kawasaki team manager Roy Turner, Mickael Pichon and Mitch Payton (far left).

“I started racing in 1984 in the 9–11 80 Beginner class, and I won my first six races at Barona Oaks,” Ryan recalls. “After I won my first race, it was like, ‘Bam! This is what I want to do! I’m going to be a professional motocross racer, because I can win on my own and I can lose on my own. That’s all I need.’”

By the time he was 16, Hughes was on the fast track to becoming a full-on factory-backed rider, nailing down the 125 A Modified and 250 A Modified titles for Team Green at the 1990 Loretta Lynn’s Amateur National Motocross Championship. Also making his professional debut in both the AMA 125cc National and 125cc West Region Supercross Series that summer, he placed inside the top 10 at every race.

“I had the ability that, if I put my mind to something, it would happen no matter what. I did everything I knew how to do the best I could. I didn’t have any fear. I wasn’t afraid to crash. I wasn’t afraid to get hurt. I wasn’t afraid to get beat. I just wanted to beat everybody so badly. I tried my hardest in every moto. Whatever my hardest was, that’s what it has always been for me.”

A LIFE CHANGING EVENT IN 1994

On Saturday night, January 12, 1991, in Orlando’s Citrus Bowl, sophomore rider Hughes came one turn away from winning the season-opening 125cc East Region Supercross main event over Brian Swink. After this promising start, his initial momentum would be slowed by a broken wrist at an exhibition race at the Fukuoka Dome in Japan. Other injuries collected along the way in 1992, and 1993 would haunt the Californian all the way to the start of the 1994 season. Once physically back up to speed for the start of the 1994 125 West Supercross series, there was another setback, one of an entirely different type—Ryan’s father was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

“He had terminal colon cancer, but at that time, it didn’t register with me what terminal was. I had blinders on. They told me my dad died when I got home from the opening round of the series at Houston. At the second race at Anaheim, I didn’t qualify.”

Brokenhearted, Hughes forged on and a week later inside Jack Murphy Stadium in his native San Diego, rode his SplitFire/Hot Wheels/Kawasaki KX125 to the first victory of his Professional career. It really couldn’t have come at a better time for the then-20-year-old. “I won that race, and it was the best thing that ever happened to me. My dad died the week before, and then I won the next race. That was a massive emotional roller coaster for me.”

The year 1994 would prove to be a breakout year for Hughes, as he would win Supercross main events in Seattle and Las Vegas, as well as the first two 125cc Nationals of his career at Unadilla and Washougal. That summer, he and SplitFire/Hot Wheels/Kawasaki team owner Mitch Payton, both extremely driven to win, would form a remarkable bond.

“I never had a problem with Mitch,” said Hughes. “It was easy to ride for Mitch. All you have to do is work hard and then you have full support from him. I’d train like crazy. I rode every day and trained every day. Mitch would call me at the end of the day and say, ‘How was it?’ I’d say, ‘Good. I did two 40-minute motos, went running and then went cycling.’ Mitch would say, ‘Good. Maybe you should go running again.’ So, I would!”

After placing second in the 1995 125cc West Supercross Series, Hughes and Payton spooled up their assault on the AMA 125cc National Championship with a convincing win at the Hangtown opener. Nineteen motos and four months later, the titanic fight for the title came down to the very last moto of the season at Steel City Raceway. By winning the opening moto of the day at Delmont, Hughes had managed to tie adversary Steve Lamson on points. The championship would be resolved in a winner-take-all 35-minute battle.

“The whole season came down to the last moto,” explained Hughes. “Steve Lamson got the holeshot, and I was third. Once I got around Mike Brown, Steve Lamson and I were 2 seconds apart for 35 minutes. I was going as fast as I could make that 125 go. Two corners from the end, we jumped and my chain broke. I already knew he had won the race, but I jumped off the bike and my mentality was, ‘Don’t stop until you get to the checkered flag.’ I pushed my bike up the hill. That’s just how I’m programmed. The chain didn’t lose me that championship, but I was full of emotion because I wanted to win that championship for my dad.”

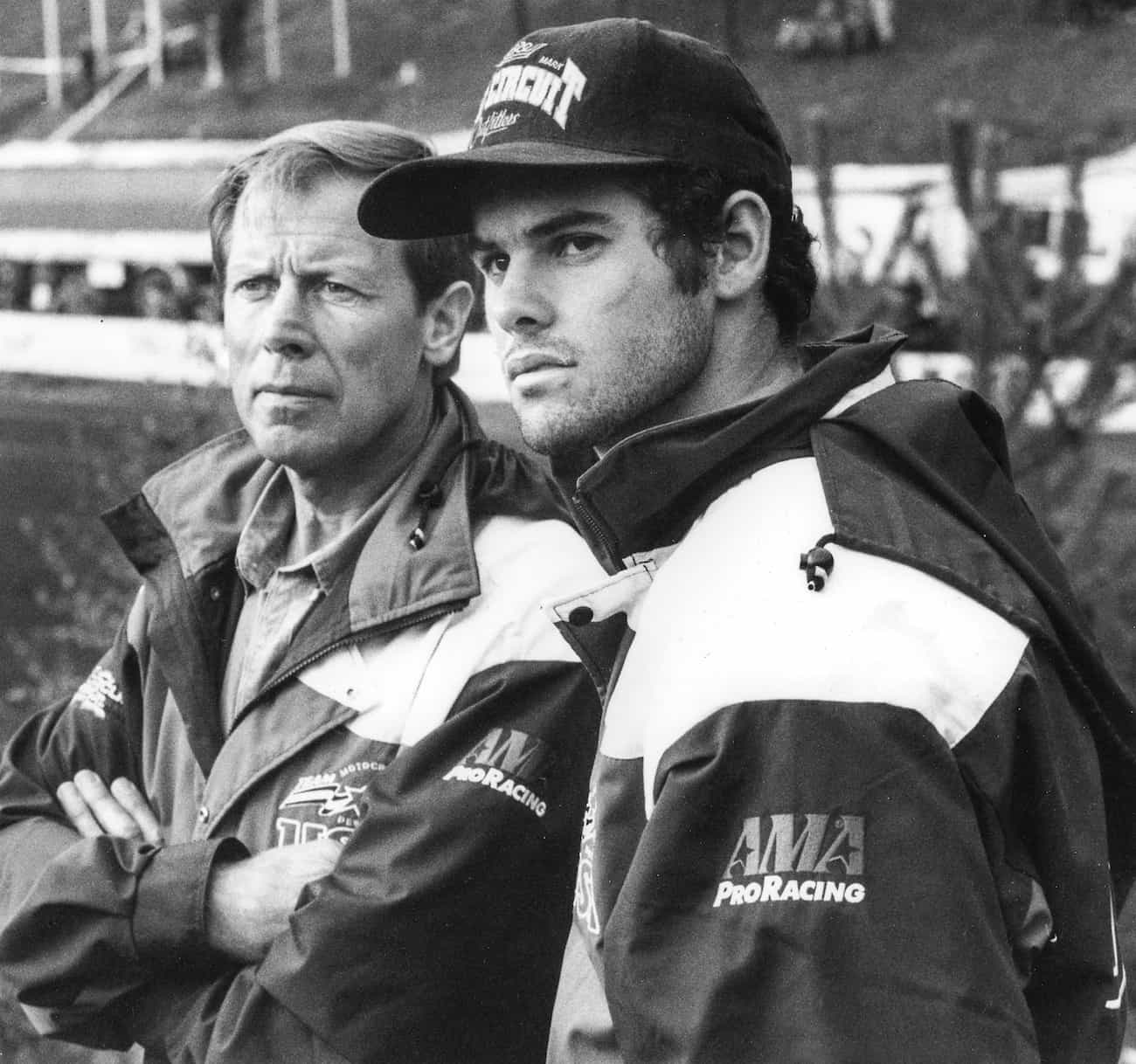

“WHEN I CAME IN FROM THE FIRST PRACTICE, I ASKED, ‘HOW DID I DO?’ ROGER DECOSTER SAID, ‘MAYBE WE MADE THE WRONG DECISION.’ I ALMOST STARTED CRYING, BECAUSE I’D NEVER BEEN 6 SECONDS SLOWER THAN ANYBODY, ANYWHERE!”

Exactly one week removed from the Steel City showdown, Ryan Hughes found himself at the Motocross des Nations in Sverepec, Slovakia. Together with teammates Jeff Emig and Steve Lamson, the trio would try to win back the Motocross des Nations title that Team USA had lost the year before in Switzerland. Bravely, Hughes, in essence a 125cc specialist at the time, had accepted the AMA’s assignment to contest the affair on a Kawasaki KX500.

“I just wanted to race, so when they asked me if I’d be interested in doing the Motocross des Nations, I said, ‘Yeah.’ Then, when they told me I’d have to ride the 500, I said, ‘Let’s do it.’ I didn’t know most of the riders’ names I’d be racing against—and I didn’t care. Of course, I’d heard of Joel Smets; he was the World Champion on his big Husaberg four-stroke. I was so cocky, I felt that I was gonna smoke this guy.”

“When I came in from the first practice, I asked, ‘How did I do?’ Roger DeCoster said, ‘Maybe we made the wrong decision.’ I almost started crying, because I’d never been 6 seconds slower than anybody, anywhere! So Mike Hooker, who was working on my bike, changed the clutch on the bike, and I brought it down to 4 seconds. Then I was like, ‘Okay, I’ve got this.’ At the end of practice, I was down to 2 seconds.”

Hughes would finish second in the opening 125/500 moto, some 7 seconds adrift of winner Smets. As fate and official Motocross des Nations scoring would have it, the brawl for the right to leave town with the Peter Chamberlain trophy would boil down to the last few minutes of the last moto of the day. For Team USA to win it, a fast-closing Hughes would need to pass 500cc class-leader Smets. Slotted between the burly Belgian World Champ and the cocky American was British 250cc rider Kurt Nicoll. At that time, Nicoll was a man who wore his disdain for all things American motocross on his jersey sleeve. Nicoll did all he could to block Hughes and, in turn, allow Smets to escape. Then, with only a handful of laps remaining, it all came crashing down for Team USA.

“Smets was a little bit faster in the first moto, but in the second moto, I was all over him. I was chasing him down and was almost there by the end of the moto. At that time, it was Europe versus America, so Kurt Nicoll was blocking me the whole time. Then, as we were going up this big rocky hill, he swapped out and I T-boned him.”

Team USA would lose the Motocross des Nations by a single point to Belgium. So, if Hughes would not have been taken down by errant Englishman Nicoll, would he have caught and passed the booming Husaberg? “Yes. One hundred percent, because in one more lap I was going to boot Kurt out of the way,” said Ryan.

No doubt encouraged by Hughes’ brilliant form, Team Kawasaki signed him to a multi-year factory 250cc contract beginning in 1996. And, it went well in the beginning, as Hughes visited the podium on several occasions until a badly broken jaw suffered in Charlotte took him out of the mix. Furthermore, knee injuries and bike issues saw an out-of-sorts Hughes lose a significant amount of momentum throughout the 1997 and 1998 seasons. In the end, his results suffered, and he found himself on the outs with longtime benefactor Kawasaki.

“Some deals fell through with people in the USA, so I wanted to do something new in 1999. I wanted to do the GPs. Also, I always wanted to ride Hondas. I liked Pamo Honda team manager Paul Kasper, and I really liked the Pamo team,” said Ryan. Although Team Pamo Honda did not receive full factory support from Honda Japan in 1999, Hughes performed quite well and was an immediate challenger in the 250cc World Championship, finding his way onto the podium in 6 of the 12 Grands Prix run that season. Remarkably fit and in the best racing condition of his career, Hughes would enter the 2000 FIM 250 World Championship as the teammate of reigning 250cc World Champion Frederic Bolley. Both riders would be sent out aboard full-on HRC works bikes. Hughes would open the season with a dazzling moto win at Talavera, Spain, and looked to be well on his way to becoming a World Champion. That dream lasted one week before Ryan suffered a wrist injury at Agueda, Portugal.

All appeared lost for the 2000 season until a phone call from the AMA gave Hughes a reason for being. “The AMA called me and asked me if I wanted to race the Motocross des Nations at St. Jean D’Angely. I still had a cast on my hand, but I said, ‘Let’s do this! I’m in.’” Before 33,000 fans on a brilliant sunny day in France, Team USA, led by Hughes’ overall victory in the Open class, won the most prestigious motocross race in the world. “That was the best moment of my life,” smiled Hughes, who stood on the victory podium with teammates Travis Pastrana and Ricky Carmichael.

RYAN HUGHES WAS LURED BACK TO THE UNITED STATES TO RACE THE PROTOTYPE HONDA CRF450 FOUR-STROKE. “THE BIKE WAS A BIT OF A HANDFUL. I GOT INJURED SO MANY TIMES THAT SEASON AND ENDED UP WITH FOUR CONCUSSIONS.”

Racing the prototype 2001 Honda CRF450 during its exemption year was not a pleasant expertence.

Racing the prototype 2001 Honda CRF450 during its exemption year was not a pleasant expertence.

During the spring of 2001, Ryan Hughes was lured back to the United States to race the prototype Honda CRF450 four-stroke. “I was going to spend the rest of my career in Europe, but then Honda called me to help develop its new four-stroke in the United States. Everything was good in practice and testing, but the bike was a bit of a handful. We were always chasing our tails. It was too heavy and didn’t turn well. I got injured so many times that season and ended up with four concussions. It was after a bad crash at the Steel City National that I said, ‘I’m done. I retire. I quit.’”

After Ryan retired, he got a job as a test rider for KTM. But, he turned out to be faster than most of the team riders, so they gave him a deal for the 2003-2004 AMA 125 Nationals.

After Ryan retired, he got a job as a test rider for KTM. But, he turned out to be faster than most of the team riders, so they gave him a deal for the 2003-2004 AMA 125 Nationals.

Ryan’s retirement lasted less than a year. Having wandered into the role of helping KTM test its race bikes, Hughes found himself faster and fitter than the KTM team riders. One thing led to another, and before the start of the 2003 AMA 125cc National Championship, Hughes had a KTM contract in front of him. Ryan was the man assigned to race the prototype Honda CRF450 four-stroke in 2001.

“I told KTM that I wanted to race the 125 Nationals. They told me that they didn’t have much money. I told them to pay me in win bonuses. Right from the get-go, I got third at my first National at Glen Helen,” said Hughes. “Then we went to Hangtown and went 1-1. This was a big moment, because I dug myself out from retiring and into leading the AMA 125 National Championship.”

THE RAINS IN OHIO FALL MAINLY ON TROY

Ryan didn’t ride off into the sunset, after he retired from AMA racing he came back to win the World Vet Championship five times (2004, 2005, 2010, 2011 and 2012).

Ryan didn’t ride off into the sunset, after he retired from AMA racing he came back to win the World Vet Championship five times (2004, 2005, 2010, 2011 and 2012).

The 2003 AMA 125 National Championship saw veterans Hughes, Red Bull KTM teammate Grant Langston and Pro Circuit/Kawasaki’s Mike Brown at each others’ throats on a moto-by-moto basis. With one race to go in the series, Ryan Hughes found himself only eight points shy of points leader Grant Langston. The final race of the season was slated for Troy, Ohio. Hughes had a good shot at the crown. Unfortunately, heavy rains and flooding had besieged southern Ohio, and Kenworthy’s Motocross Park was literally under water. The AMA, also located in Ohio, held an emergency 11th-hour meeting and decided to cancel the final race, thus giving the title to Grant Langston.

Hughes would attempt another season with the Red Bull KTM team in 2004, an abbreviated privateer campaign in 2005 and two seasons in the WORCS races with the Team Suzuki/FMF Off-Road team before finally calling an end to his racing career in 2007. Although, Ryan never ever wanted to quit. He kept coming back to race the World Vet Championship every November—winning it five times.

Tom White interviews Ryan Hughes after he won his fifth and final World Vet Championship in 2012 at Glen Helen.

Tom White interviews Ryan Hughes after he won his fifth and final World Vet Championship in 2012 at Glen Helen.

“I started Ryno Power in 2010,” explained Hughes of the Ryno Power Sports Supplements business he helps oversee. “We started with $10,000 and built it from the ground floor up. Now we’re worldwide—Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, Japan and Canada. We focus on motorsports and motocross. We also focus on mountain biking and CrossFit. I’m also involved in the Ryno Power Gym, the Ryno Institute and a new company called Ryno Equipment.”

Although he never obtained that elusive championship he was so desperate for and does not enjoy Hall of Fame numbers when it comes to total career victories, Ryan Hughes does enjoy a rich legacy and will always be remembered as a fan favorite. And, that is truly saying something. “Maybe people weren’t so much fans of me as an individual but fans of my determination and work ethic,” said Ryan.

In the decade since retiring, Ryan Hughes has not really slowed down at all. His commitment to and passion for the sport were never more evident than we he pushed his bike across the Steel City finish in 1995.

In the decade since retiring, Ryan Hughes has not really slowed down at all. His commitment to and passion for the sport were never more evident than we he pushed his bike across the Steel City finish in 1995.

Comments are closed.