TEN YEARS AGO TODAY! PULLING BACK THE BLUE CURTAIN OF JODY’S PERSONAL 2014 YZ250

By Jody Weisel

My YZ250 experience goes back to before there was a YZ — to the DT-1 250. I have raced through the Yamaha twin-shock, monoshock, dog-bone and speedo-and-tach eras. I’ve ridden white, silver, yellow, magenta and blue Yamaha YZ250s. And although I didn’t like every YZ250, I did love some of them. To me, and maybe just to me, the greatest motocross bike ever made is the 2006-2024 Yamaha YZ250 two-stroke (yes they have gotten a little monotonous over the years, but good is good even if you’re tired of it). The YZ250 epitomizes the golden era of two-stroke motocross, with just enough high-tech wizardry to make it a sweet ride today.

I think my two-stroke decision has been smarter than most of the MXA gang’s four-stroke choices, because I am a two-stroke guy at heart—albeit one who makes his living racing and testing four-strokes. And I know it was easier for me to build a full-race Yamaha YZ250 than a money sucking four-stroke, because I have built many versions of this bike over my career. I know how to make a YZ250 suit me better in my sleep.

Plus, it doesn’t matter what year YZ250 you have, can get or are searching Craigslist to find. They are all good—from 2006 all the way to 2023. Now you might think that my YZ250 would be brand new, but what for? In the interest of truth, I do have a brand new 2024 Yamaha YZ250 test bike, but my personal YZ250 is a 2014 model — and the mods I made to it, apply to every YZ250 made over the last 16 years. With the caveat that some of them are made to suit my personal peccadilloes.

These are my steps, you don’t have to follow them and you don’t have to buy any parts—because in stock trim the YZ250 is a “buy-it and race-it” bike. This is just the stuff I chose to do to my bike based on years of YZ250 experience…not to mention experience with my own personal foibles.

Aftermarket exhausts are a quick and easy way to find a couple horsepower on a two-stroke.

Aftermarket exhausts are a quick and easy way to find a couple horsepower on a two-stroke.

It helps that I have ridden Broc Glover’s, Micky Dymond’s, Damon Bradshaw’s, Rick Johnson’s, Jeremy McGrath’s and Chad Reed’s works YZ250s. And, it also helped that I had a full-race Chad Reed YZ250 of my own back in 2008 (works suspension and everything). Unfortunately, I couldn’t handle the power of Chad Reed’s engine, so I detuned it—to the dismay of Mitch Payton who thought I was crazy.

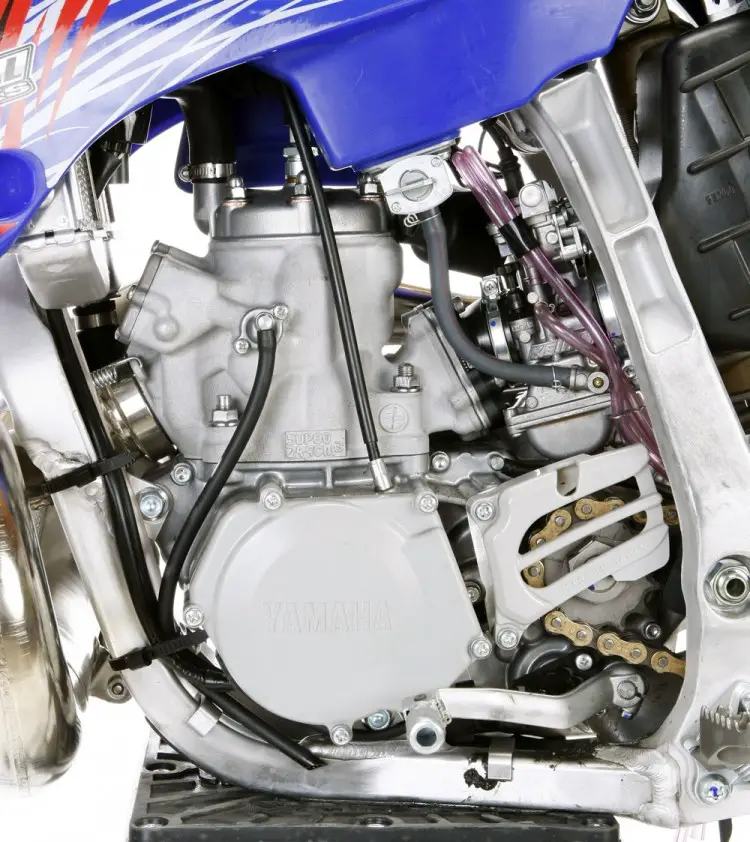

STEP ONE: For me, step one was to build an engine that was fast and powerful, but manageable. My Chad Reed YZ250 experience taught me that I didn’t need an explosive, race-gas-fueled works engine. So, when I asked Mitch to port my YZ250 engine, I turned him down when he offered to give me all the works trickery that I had back in 2008. Instead, I told him I wanted Pro Circuit’s custom porting mated to a milled cylinder head that could burn pump gas. Mitch did all the engine work himself, cost $379.95.

I try not to make my personal YZ250 a fire-breathing dragon.

I try not to make my personal YZ250 a fire-breathing dragon.

STEP TWO: In 2011, Yamaha went to a global spec on the YZ250. This meant less compression in the cylinder head and a 75mm-longer muffler—all in the name of making the bike run on gas in the Congo, as well as Beverly Hills gas. As it sits on the showroom floor, the 2013-23 Yamaha YZ250—and most of its clone-like brethren back to 2006 pump out around 46 horsepower—give or take a pony or two. I know I said that I wanted a more manageable powerband, but I didn’t want to give up four horses to a KTM 250SX or nine horses to a KX450F in the land rush to the first turn.

The porting and head mods were step one, but they were only part of my four-stage master YZ250 engine plan. The plan was simple and relatively cheap (compared to the cost of the same mods on a four-stroke). Stage two of my master plan was a Pro Circuit platinum pipe. (A younger and stupider me would have gone for the non-plated, raw-metal, Works pipe, but I don’t have the time to spend rubbing my pipe with a Scotch-Brite pad anymore.) I also added a Pro Circuit R304 silencer. It is one-half the size of the stock silencer, which is okay with me, because I don’t plan on racing in the Congo ever again after what happened last time I was there.

STEP THREE: I felt like I had money to burn, so for step three, I called Steve Tassinari and ordered up a Moto Tassinari VForce3 reed valve. This was a no-brainer, because I have historically relied on Moto Tassinari reeds when it comes to the YZ250. Plus, it (or a clone version of it) comes stock on the YZ250’s main competition, the KTM 250SX.

The unique VForce3 reed cage features double the reed-tip surface over the stock YZ250 reed. This means that the reed petals only travel half the distance for the same airflow, and they flutter less. The payoff is in an improved midrange and a better throttle response. At this point, I was still way below the price of a titanium four-stroke system—and there was only one step left in my four-stage engine plan.

STEP FOUR: One thing I learned during my Chad Reed days was that I don’t need bark as much as I need growl. I want to roll out of a turn with the throttle on and the rear wheel hooked up. As for the front wheel, it should gently paw at the air, not stand at attention. Past experience has told me that a 9-ounce Steahly flywheel weight would do the trick and since virtually every factory YZ250 racer ran a flywheel weight, I was in good company. It wouldn’t cost me any horsepower, but it would turn the rat-a-tat-tat power delivery of a ported 250 two-stroke into a broader, torquier and more tractable bike.

Since every factory YZ250 ran a flywheel weight, I knew it would smooth out the power without costing any power.

Since every factory YZ250 ran a flywheel weight, I knew it would smooth out the power without costing any power.

My total engine package (porting, head, pipe, silencer, reed and flywheel weight) cost a tad over a grand. Of course, I had a few more purchases in mind. I added one tooth to the rear sprocket (from 50 teeth to 51 teeth) and ran stiffer Pro Circuit clutch springs. It should be noted that I didn’t have an actual budget, and I was under no constraints to save money on this project. I could spend as much as I wanted, but I still didn’t want to waste money.

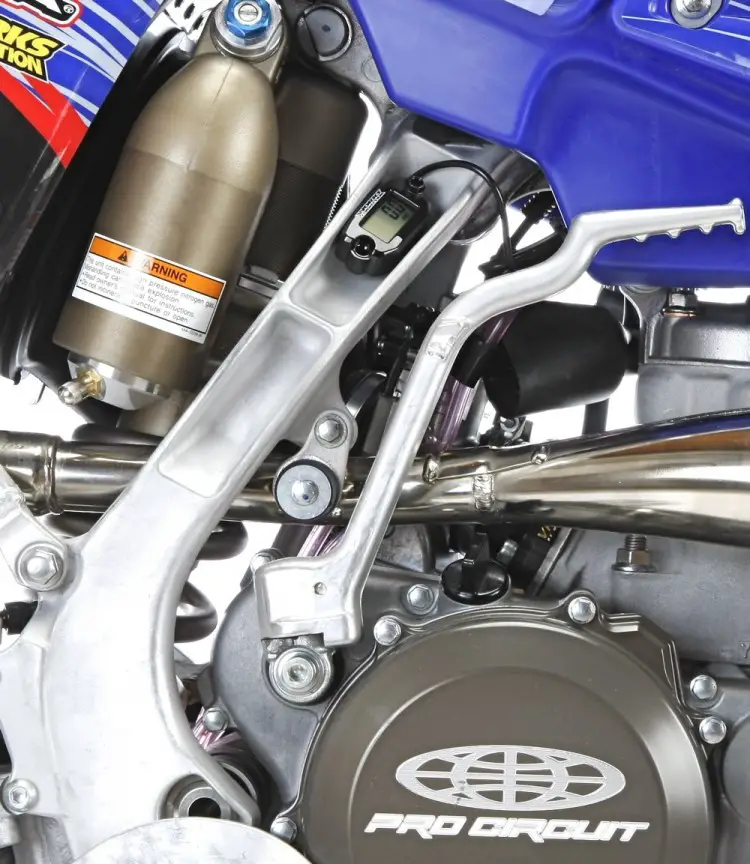

STEP FIVE: I think that the Kayaba SSS suspension is the cat’s meow of production suspension systems and on the YZ250 it is even better than on the four-strokes. Why? Because the YZ250 is only 218 pounds, and it got spec’d during a more generous R&D time at Yamaha, which meant an 18mm shock shaft and amazingly versatile damping specs.

The 2006-2024 Yamaha YZ250 has works-like suspension when compared to the stock KTM, Honda, Suzuki and Kawasaki. Many riders could buy the Yamaha and race it on the same day. But, I’m a little heavier than Yamaha’s ideal 175-pound target rider. Neither spring rate (front nor rear) will suffice for my body mass index. On the front, I can bottom the forks, and on the rear, I can’t get the proper race sag and free sag—which is a telltale sign that I need a different shock spring.

The plus for me was that I didn’t need to revalve the front or the rear. I had Pro Circuit’s Bones Bacon throw in a set of stiffer 0.45 fork springs while I went looking for a 4.9 kg/mm titanium shock spring. There was a problem. My usual source for titanium springs, DSP, was no longer carrying them. Instead, DSP had developed a new line of silicon-chromoly steel springs that had the properties of Ti and were half the price. I was thinking about going with the chromoly spring when my friend at DSP called and said that they found their last titanium spring on a dusty shelf in their warehouse. As luck would have it, it was a 4.9 kg/mm spring for a YZ250. If you could buy this spring, it would cost $600, but you can’t buy it. And since it was the last one, DSP gave it to me.

STEP SIX: Unlike you, a faster engine doesn’t make me faster; it just makes me shut off sooner. But on the off chance that I get up to speed, I need good brakes to bring me back to my senses. And “good brakes” does not mean stock Yamaha brakes. I want KTM-style pucker power, and the best way to get that is to go to an oversize rotor. I have had unbelievable luck with Moto-Master’s 270mm Flame rotor. With a larger rotor, the braking power is upped significantly across the complete friction curve, which means that there is more pucker power at low speeds and a lot more power at high speeds. It does lose some modulations, but its traded for a puckered orifice. Obviously buyers of late model YZ250’s get a 270mm rotor with each bike they buy.

This LightSpeed carbon fiber rear brake scoop may seem like so much foof, but it is based on the scoop that Jean-Michel Bayle used on his works Honda 24 years ago. Brake draggers will understand how it works and what it does.

STEP SEVEN: If there was a motocross confessional, I’d be in there every Sunday confessing that I’m a brake dragger. It comes from decades of racing with pitiful drum brakes. I don’t need more powerful rear brakes; I need brakes that don’t chirp, squeal or fade. I have several brake-saving strategies.

(1) I set my rear brake pedal up so that I barely have any brakes at all at the start, because I know that a couple of turns into the race, my brake fluid will start to expand.

(2) I run the rear brake pedal as low as it will go. On some brands, that means cutting off some of the threaded master-cylinder plunger rod.

(3) I removed the disc guards. They are there to protect the rotors from damage, but I’ve never damaged a rear rotor in my career and prefer that the rotor spins in the breeze.

(4) I run a rare LightSpeed rear-caliper air duct. This carbon fiber air scoop directs air onto the rear rotor when the bike is moving. (You don’t need to worry about braking power when you are standing still.) Don’t scoff at the idea; Jean-Michel Bayle’s works Honda had an almost identical rear-brake air duct on it.

The biggest selling motocross bike of any year is a “used” Yamaha YZ250. As long as it has SSS suspension it’s ready to roost.

STEP EIGHT: I’m not much of a frills guy. It seems silly to race a practical and affordable two-stroke and then spend money on anodized doodads. I have a Pro Circuit aluminum throttle tube (the ground keeps jumping up and cracking the stock plastic one), a LightSpeed carbon fiber glide plate (not a big skid plate), a brake snake (to keep the pedal close to the frame in ruts), and a Works Connection hour meter (Tek-screwed inside the recesses of the YZ250’s aluminum frame).

But, I’m not above a little vanity. Look closely and you’ll see a carbon fiber fork lug guard on the right fork leg, a CNC-machined billet Pro Circuit clutch cover, and a left-over Cycra YZ front fender and number plate that were especially molded to allow Yamaha two-stroke owners to upgrade their bikes to the new-generation 2015 YZ250 front fender—well, it was new generation 10 years ago. (Even though I think the new fender is ugly, it is the one YZ250 plastic piece on my bike that isn’t ten years old.)

As a final step, after the bike was completed and raced a few times, I added a complete UFO Plastic’s YZ125/250 restyle kit. It was a bolt-on kit, including radiator shrouds, both fenders, front number plate and side panels, that mimicked the look of the 2013 Yamaha YZ250F plastic. The YZ250F plastic comes from a design school known as “arrow” design—because everything ends in a point.

This Jody’s bike, the same one as above, but with the complete UFO restyle kit, which mimics the 2015 model update.

STEP NINE: I knew before I built it that there was no way that I’d be going to the starting line with the fastest bike on the track—that wasn’t what I was looking for. (Remember, I already had that back in 2008.) Instead, I wanted the best all-around bike on the track. It had to have power, not fire-breathing power, but power that I could put to the ground and keep there until the job was done. So, with my ported-and-piped YZ250 engine, I pushed the horses up to 49 while broadening the spread out with a flywheel weight and a Moto Tassinari reed cage. It ran great, and by “great” I mean I could roll it on sooner and keep it on longer. It felt connected to the ground, but was still light and airy…like a two-stroke should be.

From a suspension standpoint, I never had a worry. The Kayaba SSS suspension was flawless, and with stiffer springs, better brakes and a broad powerband, it could go where other bikes couldn’t. Well, they could, but they kicked, wheel-hopped and, in general, looked squirrelly doing it.

In the end, I loved what I built and of course, I never saw the need to upgrade to a newer model. I don’t expect you to build the same bike because I built this one for me and me alone. Your style, taste and peccadillos are different than mine. In a sport that is 90 percent man and 10 percent machine. All I wanted was 11 percent…and that’s what I got.

The most current version with a Scalvini pipe. For a 2014 it still looks good.

The most current version with a Scalvini pipe. For a 2014 it still looks good.

Comments are closed.