TEN YEARS AGO TODAY! WE RIDE WORLD CHAMP ROMAIN FEBVRE’S 2015 YZ450FM

By Daryl Ecklund

I’ve never cared much about riding factory 450s. I take that back. When I was a pimple-faced teenager, I dreamed of riding a superstar’s bike, but now Eli Tomac’s KX450F, Ryan Dungey’s 450SXF or Cole Seely’s CRF450 would be my last choice to race on any given Sunday. After you’ve tested enough works bikes as an MXA test rider, the glamor fades away. I actually dread the days when I’m assigned to test the one-off machines of the factory stars. I’m a spoiled test rider, I know, but these bikes are no fun to ride. The suspension doesn’t move. The components ricochet off every nook and cranny. The powerbands are brutal. These bikes are set up for the harsh take-offs and landings of a Supercross track. I was once an AMA National Pro; maybe, just maybe, I would have been a factory rider if I had set my bike up so that it was hard to ride.

“IN RETROSPECT, MY FIRST FEW MOMENTS ON THE TRACK WERE FUNNY. WITH A PUNCH OF THE THROTTLE, THE REAR END CAME OUT TO SAY HELLO. I WASN’T EVEN HALFWAY DOWN THE START STRAIGHT WHEN TIME SLOWED DOWN AND I THOUGHT TO MYSELF, “I’M ABOUT TO CRASH A BIKE THAT COSTS MORE THAN MY HOUSE!”

Romain Febvre’s YZ450FM is the bike of the people. It has plush suspension, an easy-to-ride powerband, electric start and comfy ergonomics—once you get used to the funky bar bend and seat hump.

Romain Febvre’s YZ450FM is the bike of the people. It has plush suspension, an easy-to-ride powerband, electric start and comfy ergonomics—once you get used to the funky bar bend and seat hump.

Which leads me to testing Romain Febvre’s Factory Yamaha YZ450FM—not just riding it at the local track, but on the famous Maggiora race track. It is obvious that many of the European stars, such as Tony Cairoli, Jeffrey Herlings and Romain Febvre, have effortless riding styles. By comparison, American riders look as if they were working hard to go fast. I started to ponder, was it man or machine that was making it look so effortless? I would get my chance to find out at Maggiora. John Basher and I had been invited to rideall the Yamaha works bikes in Italy. I felt like a pimple-faced teenager again, and you would too. I was in Italy with my buddy John riding Yamaha works bikes on one of the most iconic racetracks in the world.

My assignment was to test the bike of 2015 FIM 450 World Champion and two-time MXDN winner Romain Febvre. It was a 230-pound, electric-start Yamaha YZ450FM. Before climbing aboard the Frenchman’s steed, I chatted with Yamaha GP team manager and Romain’s mechanic Massimo Rampant about Romain’s relationship with his YZ450FM. He was transparent about every detail. It was as if he had nothing to hide (unlike the secretive U.S teams).

“I’ve worked for seven or eight riders before Romain, but it was never easy like now,” said Massimo. “The first and most important thing is that Romain knows what he wants. He doesn’t change his mind. He likes to try many things, but only on practice days. When race day comes around, he doesn’t change a thing and focuses on the track.” When I asked him what Romain was particular about and what parts he was hard on, Massimo said, “He doesn’t like the rigid feel of new frames and is sensitive to the pull of the throttle cable, which he runs a lot of play in. Romain is very easy on the engine and clutch, although he is extremely hard on the rear brake pads. He can go through three pairs on race day, as he tends to drag the rear brake.”

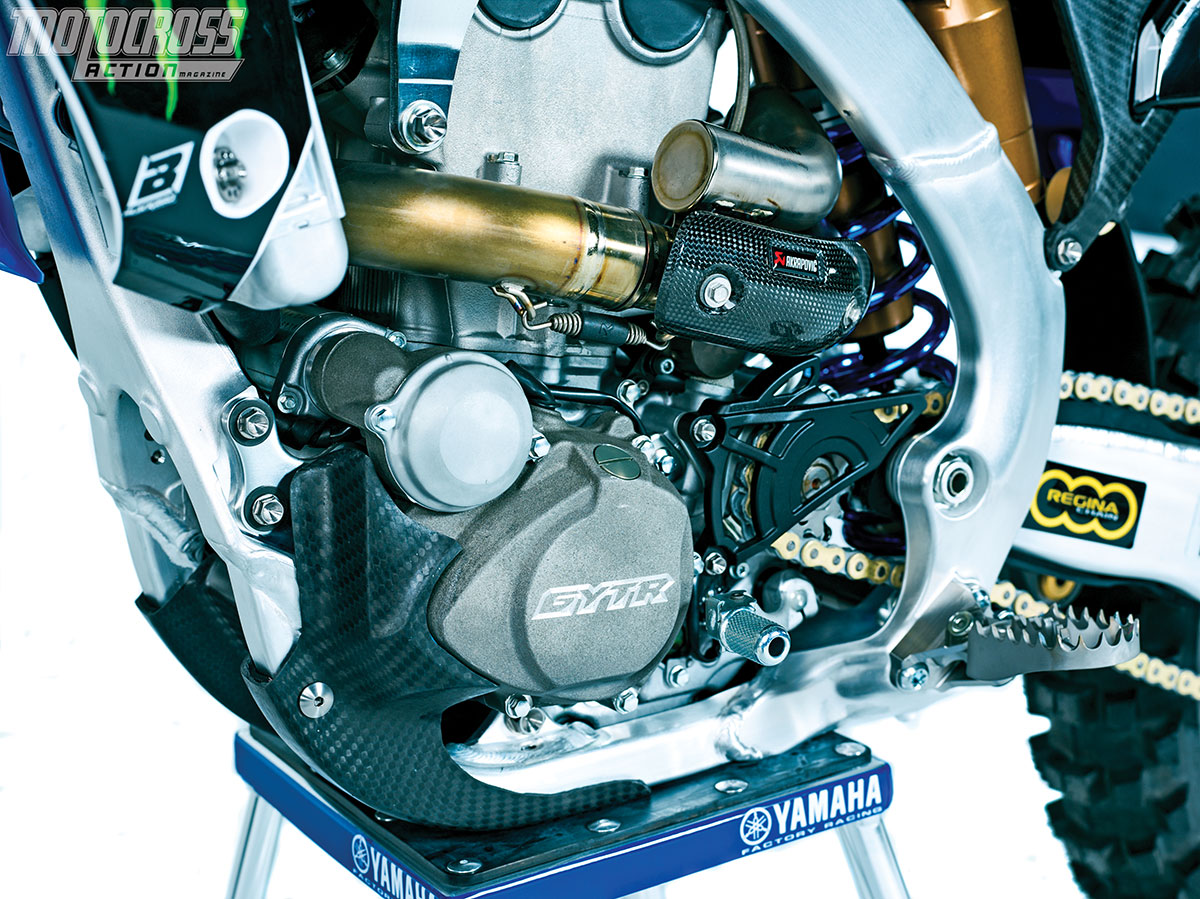

The bike itself is a work of art. All hardware, internal and external, is titanium, save for the axles (as the FIM rulebook bans Ti axles). The precious metal is accented by the carbon fiber gas tank and subframe. The total weight of the bike, without gas, is 8 pounds lighter than a standard YZ450F, and that’s with an electric starter and battery (it is, however, still 8 pounds heavier than a stock KTM 450SXF). Romain’s bike shed some weight by only using a four-speed transmission. The frame remained standard, although the rake was extended out 3mm to help with stability, and the swingarm was reinforced to add rigidity to the rear end.

When I swung a leg over the bike, the first few things I noticed were the sweptback bar bend and the hump in the seat, which I tended to sit directly on top of. Other than those two peccadilloes, all the controls were in a normal position. The pull of the Brembo hydraulic clutch was smooth, as was the throttle. For me, Romain’s desired free-play in the throttle felt incredibly strange. Overall, I felt that Romain’s setup was awkward. Having become accustomed to stereotyping these fine machines in the past, however, I was trying to have an open mind and not judge a book by its cover—at least until the rubber hit the dirt.

Riding the rough Maggiora MXDN track felt like riding in the clouds with Romain’s setup.

Riding the rough Maggiora MXDN track felt like riding in the clouds with Romain’s setup.

In retrospect, my first few moments on the track were funny. With a punch of the throttle, the rear end came out to say hello. I wasn’t even halfway down the start straight when time slowed down and I thought to myself, “I’m about to crash a bike that costs more than my house!” Unceremoniously, I slid out, with the only damage done to my ego. I turned right around and went straight back to the pits. Luckily, the pits were only 50 feet away. I thought maybe Massimo had forgotten to set the tire pressure, so I calmly asked him to set the pressure for me. “No,” Massimo replied.

Thinking that something was lost in the translation from English to Italian, I asked slower this time: “Could you set it for me, please.”

Massimo said, “No.”

I decided to try a new tack. “Can I set the tire pressure?” I asked.

“No,” said Massimo for the third time.

After the bib mousse tubes broke in, the rear end tracked to the ground like glue. The works Yamaha felt as if it had traction control.

After the bib mousse tubes broke in, the rear end tracked to the ground like glue. The works Yamaha felt as if it had traction control.

I started laughing, because this wasn’t the first time at a test ride when the factory personnel wouldn’t let me adjust tire pressure—it has become standard procedure at test rides in Europe. I decided to press a little harder, “Why not?” I asked. That is when Massimo told me that he couldn’t change the tire pressure because Romain ran bib mousses front and rear.

I got back on the bike as Massimo told me to take a few laps to break in the new mousses. Only 50 percent of the track was fully prepped. The faces of the jumps, insides of corners and the hills were in raw form. I thought the track looked challenging from the pits; riding the track was a whole other story. The lips had huge kickers on them, while the landings were ultra-steep. I’ve ridden on a wide assortment of tracks around the world, and this one caught me off guard. But as the mousses got softer, I could feel the rear end start to grip the ground, and, nestled into Romain’s cockpit (instead of sitting on top of it), I picked up the pace.

Romain’s engine purrs like a kitten rather than roaring like a lion. The 2015 450 World Champ prefers a smooth easy-to-ride powerband over brute horsepower.[

Romain’s engine purrs like a kitten rather than roaring like a lion. The 2015 450 World Champ prefers a smooth easy-to-ride powerband over brute horsepower.[

The initial part of the stroke on the forks was super soft. They absorbed small chatter like it wasn’t even there. I was concerned about jumping the bigger jumps, as I feared the forks would blow through once I hit the mid-stroke. The more I twisted the throttle, the more I realized how slow the engine felt. It had no hit. But, after overshooting a few corners, I realized the smooth, linear powerband was deceiving. I was going faster than I thought I was. This kind of power was incredibly easy to ride. It almost felt like it had traction control. For a few laps I cased or over-jumped every jump on the track. I admit to doing a few of the unfamiliar jumps with my eyes closed and fingers crossed. When the 48mm Kayaba factory air forks hit the mid-stroke, the damping ramped up enough for me not to bottom out, ever. I was shocked. The forks were the best of both worlds—soft when I wanted it and stiff when I needed it. The rear shock worked in harmony with the forks. It held up well in its stroke without much movement, and the ride height had a stinkbug feel, even though I weigh more than Romain. It didn’t shimmy at speed, and it turned on a dime, so I felt it was a win-win, even though it felt weird.

WHEN I WAS DONE TESTING ROMAIN FEBVRE’S WORKS YAMAHA, I REALIZED THAT THIS BIKE WAS NOTHING LIKE ANY FACTORY 450 I HAD EVER RIDDEN BEFORE. IT WAS ALSO UNLIKE ANY YZ450F I HAD TESTED.

The cockpit of Romain’s bike was peculiar with its swept-back bars and massive play in the throttle.

The cockpit of Romain’s bike was peculiar with its swept-back bars and massive play in the throttle.

Once I got used to the seat hump, which was way forward on the bike, and the sweptback bars, I realized the turn-in was much better into corners. The bike went where I wanted to go with ease. I started to ride the track as if the kickers and bumps weren’t there. The bike did all the work underneath me. I even forgot about the massive amount of play in the throttle. It might have actually helped me avoid whiskey throttle, as the pull was incredibly easy.

When I was done testing Romain Febvre’s works Yamaha, I realized that this bike was nothing like any factory 450 I had ever ridden before. It was also unlike any YZ450F I had ever tested. The bike still had the wide feel at the tank, but everything else felt much different than a standard YZ450F. It was a bike that virtually anyone could ride—maybe not as fast as Romain, but faster than a production bike.

Maybe if I had been born in France my Pro career would have gone on without the financial hardships and injuries. I might have been more willing to break the mold of how a bike should be set up. Romain Febvre’s setup was everything people want in a bike, even though it felt strange at first. Are American Pro riders heading in the wrong direction? Are America’s steep jump faces and longer flights more demanding? Is there a better way to set up a bike than what we have fallen into? I understand that bike setup is a matter of personal preference, but Romain Febvre’s YZ450FM is the best factory 450 I have ever ridden hands down. Could a guy like Ryan Dungey win on Romain’s bike? Of course. Ryan could win on anything he threw a leg over. And the same goes for Romain. But, the concept is food for thought.

The factory KYB air forks were plush when you wanted them to be and stiff when you needed it. The best of both worlds.

The factory KYB air forks were plush when you wanted them to be and stiff when you needed it. The best of both worlds.

All of the championship-winning bikes that I have tested over the years were blazing fast, but riding Romain Febvre’s YZ450FM proves that there is more than one way to skin a cat (although I don’t know why anyone would want cat skin). Febvre’s success proves that star power alone doesn’t make a bike great. Sometimes a racer has to think outside the box to get his bike to work for him, even if it is just for him and him alone.

Comments are closed.