MXA INTERVIEW: JEFF EMIG ON HOW EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES TOOK OVER HIS LIFE

BY JIM KIMBALL

JEFF, WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO THE ATTENTION OF THE SPORT? There was one win on minicycles that really stood out from the rest. I won the 80cc Stock class in Ponca City in 1986. That was a really coveted class win for the manufacturers, because it was on a production bike, so the OEMs loved that. I was not expected to win, but when I won that race and pulled off the track, my dad was crying because he was so happy. That became the springboard for my career.

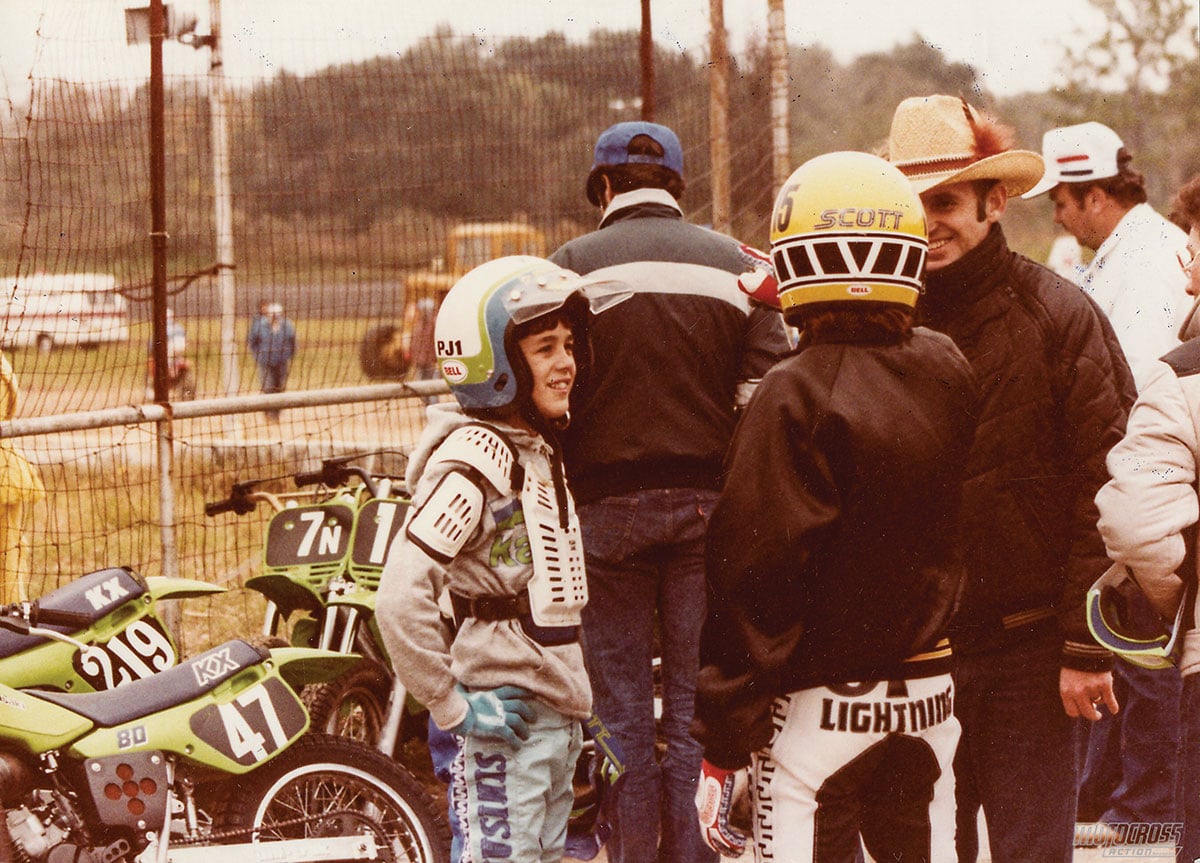

The early years of Jeff’s racing days.WERE YOU GETTING MUCH SUPPORT AT THAT TIME? Team Green was helping me. Mark Johnson was running Team Green at that time. Mark was from the Midwest, and my dad and Mark were really close. I got a Team Green deal for 1984, and I was there until I joined Factory Kawasaki in 1990.

WAS IT A NATURAL PROGRESSION TO GO TO FACTORY KAWASAKI? I wanted to ride Factory Kawasaki and be teammates with Jeff Ward. I was a Kawasaki kid from 13 years old, and that was my dream at the time. I moved from Team Green to the Factory Team to ride 125 Supercross in 1990. When I got to Factory Kawasaki, Roy Turner was the Team Manager. The team was Jeff Matiasevich, Johnny O’Mara and, of course, Jeff Ward. I filled the space as a pure 125 rider. It was a dream come true, having a box van and the whole factory team. It was very cool.

BUT YOU SWITCHED TO YAMAHA AFTER ONLY A SEASON AT KAWASAKI. WHY? I won two 125 West Supercross events, and my motocross riding was right there for Kawasaki in 1990. But Bevo Forte, who was a longtime sponsor of mine through Scott Goggles, helped guide me over to Team Yamaha. Keith McCarty was running the program. This was right about the time when Pro Circuit had its Peak Honda deal going. So, I went to Yamaha for the 1991 season to ride 125 Supercross and 125 Nationals. Unfortunately, the platform that we started with at Yamaha that year was not very good. Bob Oliver and Steve Butler, who was my mechanic, worked endlessly to get the bike up to speed, but it was tough, as the engine wasn’t the best. I struggled through 125 Supercross, but I won four races. I finished second to Jeremy McGrath by just three points.

“I GOT THROWN TO THE WOLVES IN THE 250 SUPERCROSS CLASS. I WASN’T PHYSICALLY MATURE ENOUGH AND CERTAINLY NOT MENTALLY MATURE ENOUGH. I NEEDED MORE TIME TO GROW.”

YOU QUICKLY MOVED UP TO THE 250 FOR SUPERCROSS FOR 1992? Yes, I pointed out of the 125 Supercross class, so I got thrown to the wolves in the 250 Supercross class. I wasn’t physically mature enough and certainly not mentally mature enough. I needed more time to grow. Unfortunately, because of the advancement point system, I got moved up before I was ready. Consequently, I would start up front only to get passed or crash. Supercross was bad for me in 1992, but in the 125 Nationals, I found my form as a professional racer. Halfway through the season, I started winning races and ended up winning the 125 National Championship in the final moto of the final race. I ended 1992 on a high note, winning the Motocross des Nations with Mike LaRocco and Billy Liles in Australia.

WHAT MADE YOU MOVE BACK TO KAWASAKI? After four years, I was right there, just behind Jeremy McGrath. But, I needed a change. I had been with Yamaha for a while. Off the bike, my lifestyle was really fun. We were having a good time and burning the candle at both ends. Keith McCarty and I were not really connecting on who I was as a person. He wanted me to clean up some things, have a little less fun, and be more serious about racing. I felt he wasn’t stoked on me. Yamaha gave me a great offer, but Kawasaki’s Roy Turner showed a lot of interest in me. When I signed that Kawasaki contract, it was the most money I had ever made in my career. Roy was excited to have signed me. I don’t remember Keith having that same feeling about me.

WAS THAT WHEN YOU TEAMED UP WITH JEREMY ALBRECHT? When I signed with Factory Kawasaki, I did not have a mechanic. I didn’t know what to do. Roy Turner suggested that I take a look at Jeremy Albrecht. He was mechanic at North County Yamaha. The rest is history. J-Bone and I had a great working relationship, and he also let me be me. We wanted to work hard for each other and consequently we had a really successful time at Kawasaki, winning three titles. The relationship and bond you have with your mechanic is really important, especially back then, because we didn’t have a trainer in play.

YOU WON THE 1997 SUPERCROSS CHAMPIONSHIP. WHAT HAPPENED IN 1998? From the middle of 1996 to the end of summer in 1997, I basically won everything. I was at the pinnacle of the sport, winning the 1997 Supercross and National Championships in the same year. I had been named to my sixth Motocross of Nations team and was the King of Bercy. I had the year of years. In reflection, I went in to 1998 coasting on what I had accomplished the previous year. Supercross was a real struggle, and I could not get focused. But, in the middle of summer in 1998, I regained my form. I won four outdoor Nationals and said, “Okay, things are getting back on track.” Then during practice at Millville, I rolled my right wrist forward and hurt my right thumb. I went on to win both motos that day. Then, a week later, my orthopedic surgeon said, “Your thumb is broken. We have to operate on it or you are going to mess it up even more.” I had Lasik surgery on my eyes and my thumb surgery. During this off time, I was just having fun.

WHEN KAWASAKI FOUND OUT ABOUT THE ARREST, I WAS FIRED. TALK ABOUT A REALITY CHECK. THAT WAS THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED AND THE PARTY WAS OVER.”

IN 1999, YOUR LIFE TOOK A DRASTIC TURN, DIDN’T IT? Yes. The extracurricular activities were taking over my life. In the summer of 1999, I got in trouble at Lake Havasu when the police found some marijuana in my pocket. I got arrested. Now it is legal, but back then it wasn’t. It was pretty hard to take when Kawasaki found out about the arrest. Kawasaki’s Bruce Stjernstrom called me and said, “The Japanese bosses have left the decision up to me, and we are going to let you go.” I was fired. Talk about a reality check. That was the day the music died and the party was over. At the same time, Ricky Carmichael decided he was going to work at a level that nobody before had ever put in.

YOU MAY HAVE BEEN SUPERCROSS’ FIRST ROCK STAR. It is interesting that you use that terminology. I did not have long hair, smoke cigarettes or walk around with a bottle of Jack Daniels in my hand, but, in a way, that is what I wanted to do. I never really wanted to be a professional athlete; I always wanted to be a rock star. Later on in my career, when I got the tour bus and all that, it was my way of manifesting my desire to have that rock-star lifestyle. It was certainly fun, and I had a great time. Fans loved it. It created the image that I wanted, and I felt like it was pretty authentic to me. Ultimately, it was probably not the best career choice when you are trying to be a professional motocross rider.

THAT TIME IN MOTOCROSS IS CLASSIFIED AS THE “PARTY DAYS.” TRUE? It certainly was. Back then, Keith McCarty always talked about Bob Hannah and how hard he trained. Bob was certainly a legend, but I am not Bob Hannah. I wanted to be the first “Jeff Emig.” Having a mentor is good, and beneficial, but the greats just wanted to be themselves. They didn’t want to be somebody else. For better or for worse, I wanted to do things my way. I had to learn every lesson the hard way. You can tell me, but I don’t want to listen. I am close to 50 years old now. I am an old dog, and there are no new tricks.

HOW PERVASIVE WAS THE PARTYING IN THE PRO RANKS? Although I am not going to name names, we all drank Coors Light because as the marketing said, “Coors Light won’t slow you down.” We were drinking Captain Morgan by the gallon. Some people were smoking marijuana. Some people used Cocaine, some Ecstasy, and some were eating mushrooms. That was scattered throughout all of the guys. I don’t imagine Mike LaRocco was doing any of that; some of the guys were straight edge. The guys we were racing against were all our friends. We were all doing it, so it was a bit of a level playing field. If I was at the river having a good time and Jeremy McGrath was at the river and we had to race each other next weekend, you knew it was okay. But if he was home training, then I thought I should be at home training. That is just how the era was.

AFTER YOUR FIRING, HOW DID YOU GET YOUR LIFE BACK ON TRACK? It took a couple weeks to soak in. I went to a bachelor party in Vegas, and we had a Vegas weekend. It was like something from “The Hangover” movie. At that time, I had gotten a Yamaha and was going the privateer route. The very next weekend after the bachelor party was the first round of the World Supercross Triple Crown. There were going to be three races, and the first was in Paris. It was Wednesday morning, and my mechanic came to the house said, “Hey, are you going to practice this week before we go to Paris?” I was so tore up after the lost weekend that I replied, “I don’t think I can ride.” So, we went to Paris and I ended up getting a third. All the top guys were there. I actually kept the trophy. I remember having some sort of epiphany; really looking inside and questioning myself, “Okay, what am I doing with my life?” Right after that podium, I walked across the stadium to get back to the pits. The rain was coming down, and the lights were still on, but I was alone. It was only a third-place finish, but I was really proud of myself. I remember looking up at the sky and asking, “God, please give me a sign. What do I need to do?”

DID YOU QUIT PARTYING AFTER THE THIRD AT PARIS SUPERCROSS? No. I couldn’t seem to get away from the party scene. A friend suggested that I go to rehab. I was embarrassed to realize that I was at a place in my life where I needed to go to rehab. But I went through the program, and it forced me to look at what I wanted to do with my career. I was 28 years old, but my maturity was stuck at age 18. Once I realized that, lots of good things started happening. I started my own race team. I won the U.S. Open of Supercross; not the biggest race, but it was a really important race. That off-season was the best that I had ever ridden a motorcycle in my entire career. I was so ready for the 2000 season. I was so focused and so fit that that I was like, “Carmichael, McGrath, Vuillemin, you name them, bring it on. I am going to do it, and I am going to do it on a production bike.”

WHAT WAS IT LIKE STARTING OVER AS A PRIVATEER? In the fall of 1999, I had formed my own team with support from North County Yamaha. I would drive to the Yamaha test track in my truck, with my bike in the back. That was it. No test bike, no race bike, no practice bike; I just had one bike. I had tried all the bikes, and I liked the Yamaha. I simply felt that whatever bike went through the whoops section the best was the bike that we needed to be on. I always hated whoops. My mechanic at the time, Tim Dixon, said, “If you want to be Supercross Champion again, you have to be the best guy through the whoops.” I went to Kayaba’s Ross Maeda and said, “I want you to set the chassis and suspension for me. Do what you think is best and I will figure out how to ride it. I am not going to give you input. I want you to tell me when it is going to go through the whoops the best.”

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT? My speed through the whoops improved by leaps and bounds. I would go to the Yamaha test track and Jeremy would set the fastest lap, and I would match it. I was amped to take on the world in 2000. Then a week before the first Supercross, I was riding at Stephane Roncada’s private Supercross track and I crashed. I came up short on a double and broke both wrists. This was one week before the first Supercross. I couldn’t believe it!

HOW LONG DID IT TAKE TO RECOVER? When I was in the hospital, I was really depressed. Initially I had the feeling that “this was it.” But I still had the race team with Bryan McGavran riding 125s and Phil Lawrence filling in for me on the 250. I went to the first Supercross and the fire inside of me said, “This is not how my story is going to end.” The physical therapy to get the scar tissue broken and to get the bones healed was intensely painful. But, ultimately, I got my wrists back in good shape. When I finally got back on a bike, I was focused on the 2000 AMA National Motocross Championships.

THAT LEADS US UP TO THE NATIONALS. First things first: Yamaha called because Jimmy Button, who was riding for Team Yamaha on the YZ426, suffered a really bad injury in Supercross. Yamaha wanted to give me his ride on the four-stroke. I felt that with my technique and style I would have gotten along well on the four-stroke. We tried to put together a deal but could not make the numbers work. I decided to stick with my production YZ250. Literally, less than one week later, I went to Glen Helen for the Thursday practice day. Everyone was there preparing for the Las Vegas Supercross, while the following week was the first AMA National at Glen Helen. On my third lap of practice, I came up to the finish-line tabletop pinned in third gear. When I shut the throttle off to scrub the jump, the throttle stuck. It launched me super high in the air. I took off like Superman and threw the bike away. I was so high in the air that when I landed I remember feeling all this tightness around my abdomen and back. I was looking at my boots, and I could not make my feet move. I recall thinking, “I just got paralyzed.”

WHAT WAS GOING ON IN YOUR MIND? Everyone was running up to me, and I was yelling, “Nobody touch me. I think I just broke my back. Don’t move me; I just got paralyzed.” I remember looking at the dirt and seeing every grain of sand—they looked like boulders. Then I started to feel pain in my right lower leg. What I know now is that I had a compound fracture 4 inches above my ankle. I quickly thought, “Pain is good, pain is good.” I started to wiggle my toes. I knew then I would eventually be okay, but said to myself, “I don’t want to do this anymore. It is over.”

WHAT EXACTLY WERE THE INJURIES THAT ENDED YOUR CAREER? I had to have a rod put in my lower leg and a titanium cage and rods in my back to fuse three vertebrae together.

YOU OFFICIALLY RETIRED FROM RACING, BUT YOU STILL HAD YOUR TEAM. We finished out the year on Yamahas. Then less than one year from when Bruce Stjernstrom fired me from Kawasaki, he signed my guys to be a Kawasaki support team. I think he was proud that I had taken full responsibility for my actions in Lake Havasu—publicly, personally and in magazine interviews. I did not put any blame on Kawasaki. I had signed a contract that said that I would represent myself and the company in a certain way, and I did not do that. Kawasaki had every right to fire me. I did not harbor any bad feelings. One year later, the same guy who fired me said, “Hey, we want you and your team to be back on Kawasakis.”

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE TEAM? Initially we had a fantastic deal with EdgeSports.com. They were ahead of their time during the dot-com boom. But, when the Silicon Valley bust happened, they got caught up in that. When we shut the team down, Edge Sports owed us $850,000 in payments. Our deal with them was for $750,000 a year—and we were only spending about $400,000. I thought, “This is too easy. Money grows on trees. No problem.” Then all of a sudden, money didn’t grow on trees. We were working on a deal with the U.S. Army for the 1992 season. We had multiple meetings with their marketing people, and at the last meeting we had with them, they were in.

WAS IT A HUGE MONEY DEAL? Our proposal with the Army was a three-year deal for three million dollars a year. At the time, it would have been one of the biggest budgets in the sport—and we were just a satellite team. I was like, “Wow, this is too easy.” So, we lost the sponsor that was supposed to pay us $750,000 a year and were going to pick up the U.S. Army for $3 million a year. We would have two semis, one for the race team and one for hospitality. If that sounds familiar, it’s because that is what teams do now. We would have had enough money to buy any rider we wanted. Then the call came down that they were dropping out of the deal, and when that deal did not materialize, I said, “I am done. I am shutting the team down. I just need to relax and be retired for a while.”

“DURING MY TIME AS A RACER, DAVID BAILEY WAS ALWAYS SO HARD ON ME WHEN HE WAS THE TV ANALYST. I GET IT NOW, AND I RESPECT HIS CHOICE OF HOW HE WANTED TO CALL THE RACES. LOOKING BACK, HE WAS RIGHT MOST OF THE TIME, UNFORTUNATELY.”

WHEN DID YOUR TV BROADCASTING CAREER START? I did some broadcasting in 2002. I joined the broadcast team as a pit reporter, but I did not want to do pit reporting. I wanted to be in the broadcast booth. As a pit reporter, I was really uncomfortable at times. I had not been away from the racing side of things long enough to really have perspective on the sport. I did that for one Supercross season, and it was not a memorable experience. Years later, around 2006, when the opportunity came to join the broadcast team, I jumped on it and started my career as a broadcaster. I did that for 12 seasons, and it was an amazing experience. We had such a fantastic chemistry with everyone on the broadcast, especially the last few years.

YOU BROUGHT A VERY GOOD PERSPECTIVE BECAUSE YOU WERE A FORMER CHAMP WHO COULD CRITIQUE THE RIDERS BUT NOT TALK NEGATIVELY ABOUT THEM. I am glad that you recognize that. I always felt that during my time as a racer, David Bailey was so hard on me when he was the TV analyst. I get it now, and I respect his choice of how he wanted to call the races. Looking back, he was right most of the time, unfortunately. I never wanted to say that the guy who got second was the first loser. No one on a Supercross track is a loser. A guy may finish 19th, but 19th against the best Supercross racers in the world is something to be proud of. I wanted to celebrate the guy who got 19th. How many people get to say something like that? Thankfully, during my time in the booth, the fans enjoyed what I brought to the broadcast.

DID RICKY CARMICHAEL TAKE YOUR JOB? Yes, that jerk took my job! No, I am kidding. Ricky is one of my dearest friends, and I wish him the best. When the broadcast contract moved from Fox Sports to NBC Sports, they decided to make some talent changes, I was not offered the position. If it was not going to be me, I would rather it be Ricky.

WHAT IS YOUR LIFE LIKE NOW? I am super busy. I am trying to work hard and create opportunities for myself business-wise in the future. I am on my 25th year with Fox Racing/Shift MX. I have my collaboration with ODI grips that has been a great partnership. I love doing the broadcast contracts that I have with the Motocross des Nations and the MXGP broadcasts. The last couple of years, Ricky Carmichael and I created a Podcast called “Real Talk 447,” so that gives me that outlet to still have a voice in the industry. We keep growing the podcast with each and every show. I do miss being on the Supercross broadcasts. I miss that family of co-workers, the excitement that comes with being in the broadcast booth, and the anticipation over what is going to happen.

ARE YOU STILL A FAN OF THE SPORT? It has been tough at times. I took a step back when I didn’t get signed to do Supercross broadcasts. I really needed to distance myself from it. Lately, I have been to more races. I still consider myself a racer. That is how I am going to identify myself for the rest of my life. It has been a full life, and hopefully I am going to make my life expectancy well past the 80s, so I can see my kids have kids and have more life experiences, but I am telling you, if it all ended today, I have been a lucky man.

Comments are closed.