MXA RETRO TEST: WE RIDE MIKE KIEDROWSKI’S 1990 FACTORY HONDA CR125

We get misty-eyed sometimes thinking about past bikes we loved and those that should remain forgotten. We take you on a trip down memory lane with bike tests that got filed away and disregarded in the MXA archives. We reminisce on a piece of moto history that has been resurrected. Here is our test of Mike Kiedrowski’s 1990 factory Honda CR125.

There are industry insiders who insist that the production rule did nothing to lower the cost of professional racing. They claim that it just shifted the priorities of where the money was spent. When the teams had $50,000 one-off bikes, they had a plum that could guarantee them a great rider for less money. After all, a works bike was going to be worth a lot of purse and bonus money, so why not sign for less to get your hands on one? When the production rule passed and bikes had to be based on showroom-stock bikes, the riders’ salaries jumped significantly. They realized that if all the riders on the starting line were going to be on equal equipment, then great riders were worth more money than good riders. The cost of fielding a team didn’t change in the direction that the rule makers had hoped.

WE REMINISCE ON A PIECE OF MOTO HISTORY THAT HAS BEEN RESURRECTED. HERE IS OUR TEST OF MIKE KIEDROWSKI’S 1990 FACTORY HONDA CR125.

Compounding the cost factor was the reality that a great rider was no guarantee of victory; he still needed a great bike. Production bikes may be cheaper to start with, but when you try to turn one into a works bike after the fact, they begin to rival the cost of vacationing in Kuwait.

Honda had the best works bikes. Honda has the biggest racing budget. Honda has the best win-loss record in AMA competition. It’s logical to extrapolate that Honda spends the most money building works-like production bikes.

The MXA wrecking crew wanted to find out just how good a 1990 factory Honda is.

HOW COULD WE GET OUR HANDS ON ONE?

How could we get Team Honda to hand us over 1989 125 National Champion Mike Kiedrowski’s 1990 works Honda CR125? We plotted late into the night. First, we called Mitch Payton at Pro Circuit. Pro Circuit has the contract to run the factory Honda 125 effort for 1991. If anybody could get us a works Honda, it should be the guy in charge of them. We asked Mitch to use his influence over at the factory to open some doors. Next, we called Roger DeCoster. Roger is in charge of Honda’s worldwide motocross effort, and he had the power to hand-carry our request up to the head offices. Along the way, we mentioned that we had already ridden Damon Bradshaw’s Yamaha and Alex Puzar’s Suzuki. We were sure that Honda wouldn’t want us to leave them out.

ABOUT A WEEK LATER, ROGER CALLED. “MXA CAN RIDE MIKE’S BIKE. WE THINK IT WOULD BE GOOD TO GET MORE INPUT AND PUBLICITY. YOU NAME THE TRACK, AND WE’LL HAVE A BOX VAN AND MECHANIC THERE.”

About a week later, Roger called. “MXA can ride Mike’s bike. We think it would be good to get more input and publicity. You name the track, and we’ll have a box van and mechanic there.”

They did. Three days later, Mike Kiedrowski’s factory Honda mechanic Ron Wood drove through the gates of Perris Raceway. His instructions were to tell us anything we wanted to know, keep the bikes running as long as we liked, and help us dial in our own stock 1991 CR125. The MXA test crew was eager to ride a factory Honda, especially one with the #1 plate on it.

WHAT’S IT ALL ABOUT?

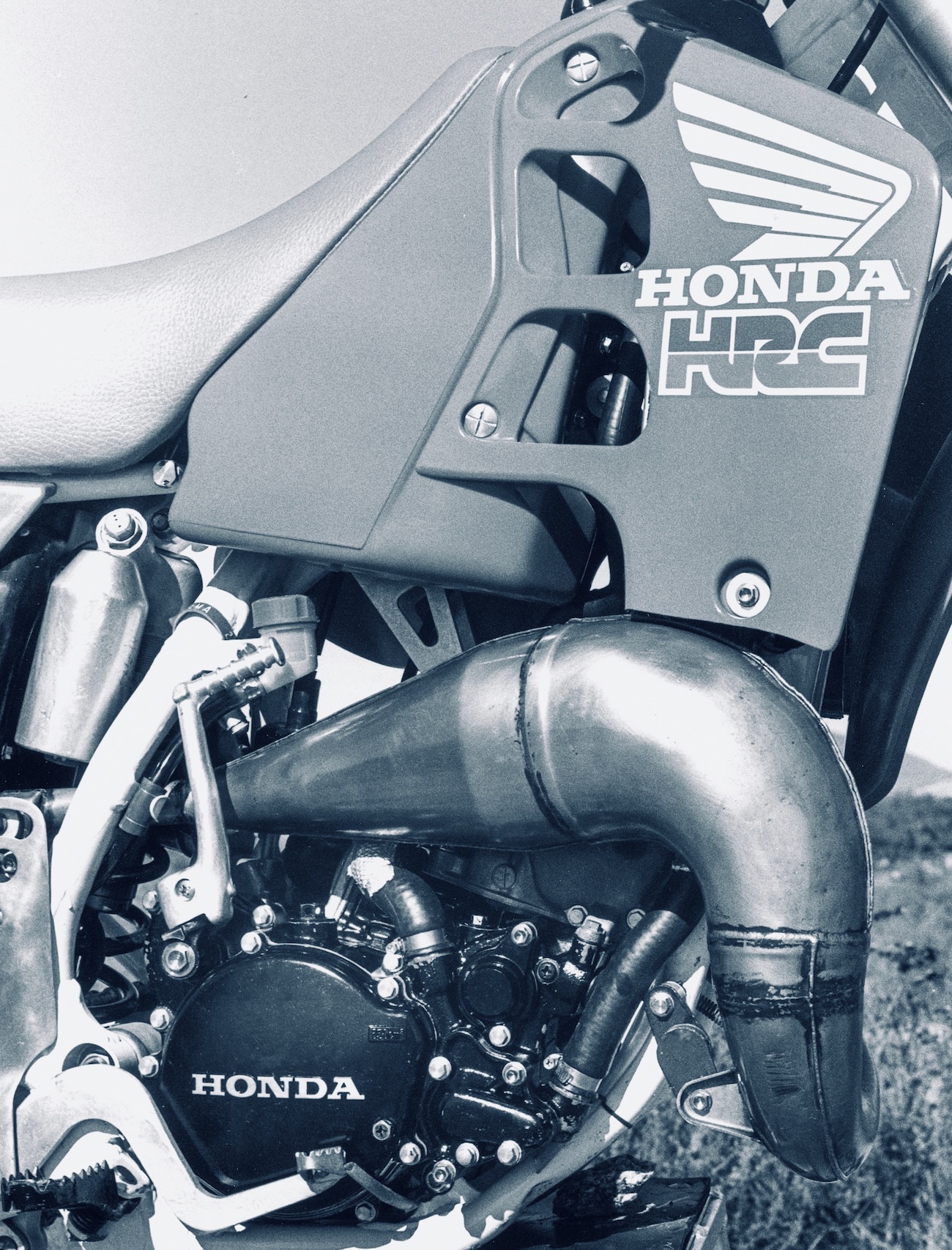

Before we threw a leg over Mike Kiedrowski’s factory CR125, we decided to take a tour of the bike from the front to back.

Tires: Mike’s main choice of rubber is a Dunlop K490 front tire with a K695 rear. For sand tracks, he switches to a Dunlop 752 or 701 (test tire).

Wheels: The rims are D.I.Ds laced to magnesium hubs. The mag hubs save 3 pounds per wheel when used with aluminum spoke nipples. We had expected to find titanium axles, but the factory Honda used steel axles with aluminum axle nuts and chain adjusters.

Brakes: There is nothing about the factory CR125 brakes that are stock. The master cylinder is a Nissin works unit. A braided-steel brake line leads down to a special set of calipers and brake pads. The rotors have the same diameter as stock but are made out of a higher grade of steel that has been specially ground.

The front brake lever is shorter than the stock unit and is wrapped with bicycle handlebar tape to improve the rider’s grip. Mike likes his front brake set up with a lot of play in the lever. Team Honda has a choice of three different-length rear brake pedals. Kiedrowski uses the medium-length pedal.

Forks: The forks are 45mm magnesium Showa works forks. Most of the bolts and hardware on the forks are titanium. The top triple clamp is cast out of magnesium also, but the lower triple clamp is aluminum.

The rider can choose the amount of offset he wants in his forks by switching the collar in the upper clamps.

Shock: Surprisingly, Mike Kiedrowski’s shock uses a stock Showa body but with totally re-valved internals. The rear spring was unpainted for no reason other than to save a little weight and to keep the paint from flaking off. The piggyback shock mounts to machined billet shock linkages. The linkage connects to a standard CR125 swingarm with a titanium pivot bolt. Steel bolts are used in the linkage itself, but they are special bolts manufactured to fit the machined link arms.

Carburetor: We had expected to find an ultra-trick magnesium carb, but a stock 36mm Keihin did the chores. The only visible modification to the carb was an enlarged float bowl to lessen fuel starvation at high speeds. The main jet was a 162.

Ron Wood had drilled large holes in the airbox and covered them with a screen to keep big chunks of dirt from hitting the Twin-Air filter.

Engine: Team Honda didn’t want us to look inside the cylinder to discover what kinds of tricks they were using to make National Championship-winning power. Luckily, we have used our belt-buckle camera enough times at the 125 Nationals to have a pretty good idea of the internal dimensions. The porting and HPP valves are perfectly mated to one another. The porting specs come directly from HRC of Japan, and Kiedrowski’s porting is different from teammate Jean-Michel Bayle’s. While Ron Wood was insistent that the bike used stock internals, we know that the rod is a specially made part. The reed block is HRC (the reed petals are stock), and the power-valve mechanism has turnbuckle-style adjusters that allow the valve to be degree’d to open and close at selected spots (a giveaway that something was different in the HPP valve mechanism is the sand-cast HRC power valve cover). It’s likely that the crank halves are also balanced and weighted to provide maximum inertia.

The clutch uses an HRC basket and special fiber plates.

The pipe is a stamped, built-in-Japan, HRC unit that is designed to suit Kiedrowski’s interest in midrange power.

ROGER HAD TOLD US THAT MIKE KIEDROWSKI’S BIKE WAS SET UP SPECIALLY FOR MIKE AND THAT IT WASN’T THE SAME POWERBAND THAT AS USED BY JEAN-MICHEL BAYLE.

Miscellaneous: Titanium bolts are everywhere, including the motor mount bolts. The footpegs are cast alloy and are, of course, wider than stock. AFAM provides the sprockets (Kiedrowski almost always runs 13-52 instead of the stock 13-51) and the chain is a DID. Daeco supplies the fuel, and Hondaline is the chemical supplier for Team Honda. Wood runs an NGK B8EV plug. Handlebars are Renthal 722s equipped with stock Honda grips that have the top shaved off with a razor blade.

Mike uses a stock Honda saddle but has a new one mounted every three races to keep the seat foam firm.

The ready-for-tech-inspection weight is 198 pounds.

LET’S RIDE IT

Roger had told us that Mike Kiedrowski’s bike was set up specially for Mike and that it wasn’t the same powerband that was used by Jean-Michel Bayle. The difference, Roger explained, was that Bayle liked a hard-hitting midrange and a ton of top-end, while Mike wanted his engine to hit lower and not rev as far. In all sincerity, Roger said that he would be interested in finding out what we thought about Mike’s engine.

To be perfectly honest, to you and to Roger, we weren’t totally in awe of Mike’s powerband choice. There is no doubt that Kiedrowski’s factory CR125 made competitive horsepower; after all, it won the Gainesville, Binghamton, Steel City and Budds Creek 125 Nationals. Every test rider remarked about the dead-center power, but we came away more impressed with Mike Kiedrowski than with the Honda’s engine. Ron Wood had worked hard to get the engine to run the way that Mike wanted it, so we have to assume that Mike can make it work better than we could.

When Roger called to find out what we thought about Mike’s bike, we babbled on about how great the suspension had been (it was unbelievably good). We told Roger how much quicker the handling felt than that of the stock bike. It wanted to turn in the corners, and it didn’t suffer from half the head-shake of a stocker. We thanked him for his efforts and tried to change the subject.

“What about the engine?” pursued Roger. “Who are we to complain about a National Champion’s bike?” we asked, and then started to complain. “The power is decidedly midrange, but it was soft on the bottom and signed off on top. When you came out of a turn and nailed the throttle perfectly, the bike was awesomely fast. It roosted, but if you bobbled a little or had some lag in the right wrist, it bogged. It was a mysterious powerband to us. We’d do a couple of laps absolutely ripping and then flog a few turns and feel like total spodes.”

“Was it fast?” asked Rog.

“Sure it was, but it wasn’t easy to ride,” we replied. “It signed off early, so we had to shift a lot. Even a stock CR125 is renowned for its ability to rev to the moon. Not Mike’s bike! The listless bottom, lack of top and shifting midrange power made Kiedrowski’s bike harder to ride fast. The faster you went, the better it worked, but it was easy to over-rev the powerband or shift too soon and miss the shifting midrange.”

“What do you mean shifting midrange?” questioned Roger defensively. We knew that we would hurt Honda’s feelings if we picked on their powerband, but Roger was asking.

“It was never in the same place twice,” we answered. “Sometimes the midrange would hook up early, and the next corner it wouldn’t grab until 1000 rpm later. It seemed to be load- and speed-sensitive. When you did it perfectly you could fly, but we weren’t perfect all the time. We really expected a factory Honda to hit super hard in the midrange and just blow out the cobwebs until the rod stretches. The shortness of the powerband seemed odd.”

“You would love Jean-Michel’s 125. It is more of a midrange-and-up bike. Mike prefers to have a midrange-only engine, and that was built just for him,” explained Roger.

WHAT’S IT ALL MEAN?

It means that Mike Kiedrowski is a rider of exceptional talent who not only knows how to ride but how he wants his bike to run. Luckily, a factory bike—and the cubic dollars that go into making one—gives a rider the freedom to fine-tune the machine to his personal tastes. Whether it’s the little things like a selection of rear brake pedals or expensive components like adjustable triple clamps, a factory effort is a thing of beauty. Great suspension, dialed-in handling and a personalized powerband.

Comments are closed.