1968 YAMAHA DT1: THE BEST THING THAT EVER HAPPENED TO MOTOCROSS

By Jody Weisel (with aid and support from Dave Holeman, the Fergus family, Ed Scheidler, Tom White and Yamaha)

The best thing that ever happened to the sport of motocross was the introduction of the 1968 Yamaha DT-1. Nothing like it existed before, and, more than likely, nothing like it will ever appear again. The 1968 DT-1 is not a bike you would look at today and immediately understand the inspiration that spawned it, but in those fledgling off-road years of the 1960s, the DT-1 was to motorcycling what the electric guitar was to rock ’n’ roll.

The startling impact of the 1968 Yamaha DT-1 is what lured you, me, your dad, your brothers and a host of American teenagers off of the baseball diamonds, out of the movie theaters and away from street corners for the thrill of a lifetime. It was a watershed piece of motocross history. How did it happen, and has it really meant that much?

THE CLOCKMAKER’S DREAM COMES TRUE

Torakusu Yamaha never saw a motorcycle. While part of his story involves an amazing 200-mile journey, it was on foot that he approached his place in history, not on a motorcycle. Born in 1851, Torakusu Yamaha worked as a skilled clockmaker and meticulous craftsman. His reputation as a man who could fix anything led to a job that was going to change his life and, in time, off-road motorcycling. In 1887 the city of Hamamatsu had gained possession of an American-made organ. This wondrous musical instrument was a rarity in 19th century Japan, and the people of Hamamatsu would gather in droves to hear it play on the one day a month that the city fathers allowed public recitals. As the crowds grew larger at every recital, you can imagine the scene when the organ broke down. Nobody in Hamamatsu had ever seen an organ, let alone repaired one. Enter Torakusu Yamaha. He not only repaired the organ, he also became so fascinated with the musical instrument that he built his own harmonium version from scratch (a harmonium is similar to an organ in that it makes sound by blowing air through reeds, which are tuned to different pitches to make musical notes). After months of work, Torakusu decided to take his instrument to the Japanese Music Certification Office in Tokyo. Unfortunately, the only way to get the instrument to Tokyo was to carry it 200 miles, which he did!

Yamaha’s harmonium failed to pass the music certification, but a year later his second version not only passed the test, it was declared to be of equal quality to any instrument, foreign or domestic, in Japan. Thus, Torakusu Yamaha went into the piano and organ business. He died in 1916. His company did not produce a motorcycle for another 40 years.

SINCEREST FLATTERY OF THE IMITATION KIND

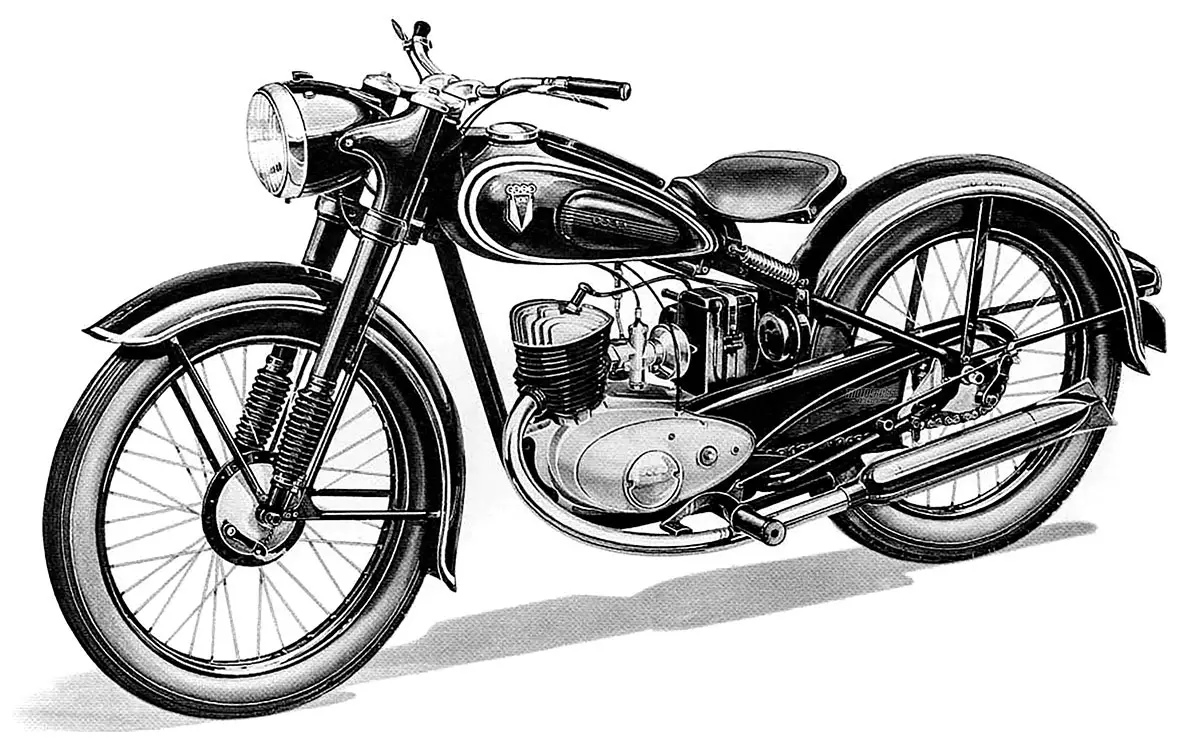

Look closely at this German-made DKW RT-125 and you will see where the YA1 came from.

Look closely at this German-made DKW RT-125 and you will see where the YA1 came from.

The first Yamaha motorcycle was a ripoff. In 1955, there were over 100 motorcycle manufacturers fighting over the Japanese market. Yamaha was just entering the motorcycle business and faced the wrath of the already established marques of Lilac, Marusha, Tohatsu, Showa, Meguro, Miyata and Honda. In order to guarantee that their machine would be competitive and successful, Yamaha’s management decided not to risk everything on an unproven Japanese design. Instead, Yamaha made a near copy of the historically significant, German-built DKW RT-125. DKW had been building two-stroke engines since 1919, and Yamaha’s 1955 YA1 was a 123cc Japanese version of Das Kleine Wunder (DKW).

When Yamaha won the 1955 Mount Asama Volcano race on this souped-up YA1, every motorcycle fan in Japan wanted to buy a “Red Dragonfly.”

When Yamaha won the 1955 Mount Asama Volcano race on this souped-up YA1, every motorcycle fan in Japan wanted to buy a “Red Dragonfly.”

But, how could they get the public to recognize Yamaha as a major player in the crowded Japanese motorcycle market? Yamaha decided to go racing. Yamaha won the first race it ever entered. In order to make its 1955 YA1 come to the immediate attention of the Japanese public, Yamaha entered a team of its bikes in the Mount Asama Volcano Race. The Asama Volcano Race was a 12.5-mile race up the shifting volcanic ash roads of a mountain situated 120 miles north of Tokyo. The fledgling Yamaha team shocked the other manufacturers by winning the Asama Volcano Race. Instant sales success! Young Japanese riders flocked to buy the YA1 “Red Dragonfly.”

YAMAHA COMES TO AMERICA…SANTA CATALINA TO BE EXACT

Fumio Itoh (33) and his Yamaha YD-B 250 twin on the starting line at the 1958 Catalina Grand Prix.

Fumio Itoh (33) and his Yamaha YD-B 250 twin on the starting line at the 1958 Catalina Grand Prix.

Thousands of miles away from Mount Asama lay Santa Catalina island. Catalina is a small resort island 23 miles off the coast of Southern California. In the 1950s, the island, owned by the Wrigley Chewing Gum heirs, had a reputation as a holiday playground for the rich. It was also the scene of one of the most unique motorcycle races in the world—the Catalina Grand Prix. The race course started in the seaside city of Avalon and wound its way up mountainous gravel roads before plunging back out of the hills and down into the island resort town.

It was at Catalina that Yamaha made its first overseas appearance. The year was 1958. The machine was the 249cc twin-cylinder Yamaha YD. The rider’s name was Fumio Itoh. The competition was BSA, NSU, DKW and Triumph. Winners of the Catalina Grand Prix included Feets Minert, Bud Ekins, Dave Ekins and, no, that list did not include Itoh and his YD. But, his sixth-place finish from dead last buoyed the hopes of Yamaha, and the plan to go racing outside of Japan was formulated.

SEALING YOUR OWN FATE

Husqvarna dropped Torsten Hallman from their factory team because he was too old. Yamaha snapped up the four-time World Champion to turn the DT-1 into a motocross bike.

Husqvarna dropped Torsten Hallman from their factory team because he was too old. Yamaha snapped up the four-time World Champion to turn the DT-1 into a motocross bike.

Corporate avarice can sometimes be beneficial. Torsten Hallman had earned Husqvarna four 250 World Championships in the rugged world of European motocross, but by 1970 Torsten was of little value to the Swedish manufacturer. An ailing back and 14 years of service at Husky meant that his championship hopes were waning. Husqvarna wanted to put its resources into young rising stars Heikki Mikkola and Hakan Andersson.

To get rid of Torsten, Husky offered Hallman a pittance of his previous contract, believing that he would turn it down and disappear into retirement. Torsten did turn Husqvarna’s offer down, just in time to receive a phone call from Yamaha. Yamaha asked the four-time champ to ride its new, untested prototype motocross bike for a one-time test session. Torsten rode the bike and told Yamaha that the bike needed a complete development program and he was their man. Torsten Hallman signed a three-year contract for more money than Husky ever paid him. Best of all, Torsten’s R&D work was going to culminate in the development of the first YZ and Yamaha’s first World Motocross Championship. Husky’s plan to dump its old, loyal employee paid off—for Yamaha.

GETTING SPIT OFF A CZ IS A GOOD THING

Hakan Andersson’s monoshock 250 World Championship YZ250.

In the early 1970s Lucien Tilkens had a son who raced CZs, and Tilkens was depressed by how often his kid was pitched over the bars. Tilkens, a professor at Liege Engineering College in Belgium, believed he had a solution. Stealing a little design inspiration from Vincent road bikes of the early 1950s, Tilkens built his son a Monoshock CZ. Encouraged by the fact that his son was eating dirt less often on the single-shock CZ, Tilkens called on his friend Roger DeCoster, a factory Suzuki rider, to come over and test the machine. Roger did. He loved it. DeCoster called Suzuki and told them about Tilkens’ Monoshock design. Suzuki took a look at the Monoshock concept and told DeCoster that it was not a good idea. Immediately after Suzuki turned Tilkens down, Lucien Tilkens received a phone call from Yamaha. Two years later, Yamaha’s Monoshock YZ250 would win the 250 World Motocross Championship.

But, we are getting ahead of ourselves. Hallman, YZs, Monoshocks and World Championships were all instrumental in Yamaha’s success, but that success would not have been possible without the development of the Yamaha DT1.

This is what American off-road racers thought was the best bike made for the American desert—until the arrival of lightweight two-strokes.

In the early 1960s Americans were interested in riding motorcycles off-road. And there were lots of motorcycles for them to ride—if they could work with their hands, speak Spanish or knew which way to turn a Whitworth bolt. Triumph, Greeves, BSA, Bultaco, Montesa, DKW and all manner of street machines were modified to ride in the desert and trails of North America. Desert sleds were the order of the day, as California desert racers piloted 350-pound, twin-cylinder, British four-strokes across the Mojave. You either bought a one-off European race bike, which had very little parts support, or you modified a British sled and went racing.

One of the young motorcycle racers out in the desert in 1966 was a Yamaha employee named Dave Holeman. Holeman loved desert racing, and he talked a buddy of his at Yamaha into going out with him to a couple of races. Dave’s buddy was Jack Hoel, who just happened to be in charge of Research and Development at Yamaha USA. Jack was an accomplished rider, and his father, Pappy Hoel, was the founder of the Black Hills Rally. After Hoel and Holeman had spent some time in the desert and had seen the mix-and-match style of equipment being raced, they were convinced that Yamaha could produce a machine that would suit this market. Shades of the 1955 YA1, the 1966 Montesa Texas Scorpion 250 was the European bike that Yamaha copied when it decided to build a 250cc dual-purpose dirt bike.

Shades of the 1955 YA1, the 1966 Montesa Texas Scorpion 250 was the European bike that Yamaha copied when it decided to build a 250cc dual-purpose dirt bike.

What they needed, assessed Holeman and Hoel, was a lightweight, durable, 250cc motorcycle that you could ride to work Monday through Friday and strip down for racing on the weekends. But, the fact that the two Americans thought they had a great idea didn’t mean anyone else at Yamaha would believe them. This kind of bike had never been built by the Japanese, who preferred to take twin-cylinder, two-stroke and four-stroke street bikes, add up-pipes and a racy name (like Big Bear Scrambler) and sell those as dual-purpose bikes.

Before the DT-1 came along, this is what Yamaha thought was a dirt bike — the twin-cylinder YDS1 Scrambler.

Hoel approached his Japanese bosses in Los Angeles with the idea of a 250cc trail bike, and they liked the idea enough to suggest further study. Holeman and Hoel knew what they wanted, but neither of them knew how to build it, so they went looking for what was available from the European brands that fit the profile of a dual-purpose dirt bike. They looked at Bultaco Camperas, Matadors and Pursangs. They rode Greeves and DKWs. Their search continued until they found the best of the breed—the Montesa Texas Scorpion. The Texas, a Montesa spin-off from the Montesa Impala and LaCross 66, was intended for an American audience only. It was a 250cc, single-cylinder, four-speed, two-stroke that was street legal. The Texas came with dual-purpose tires, a pop-off headlight nacelle, aluminum rims and a double leading-shoe front drum brake. Strangely enough, the Montesa Texas Scorpion was only offered in Spain in 1966 as a 175cc model—and only 186 were made (compared to 2400 United States-bound Texas 250s). Hoel and Holeman knew that Montesa was no threat to sell enough Scorpions to scuttle their dual-purpose plans, since the Spanish did not have an extensive American dealer network.

MEANWHILE, BACK AT YAMAHA HEADQUARTERS

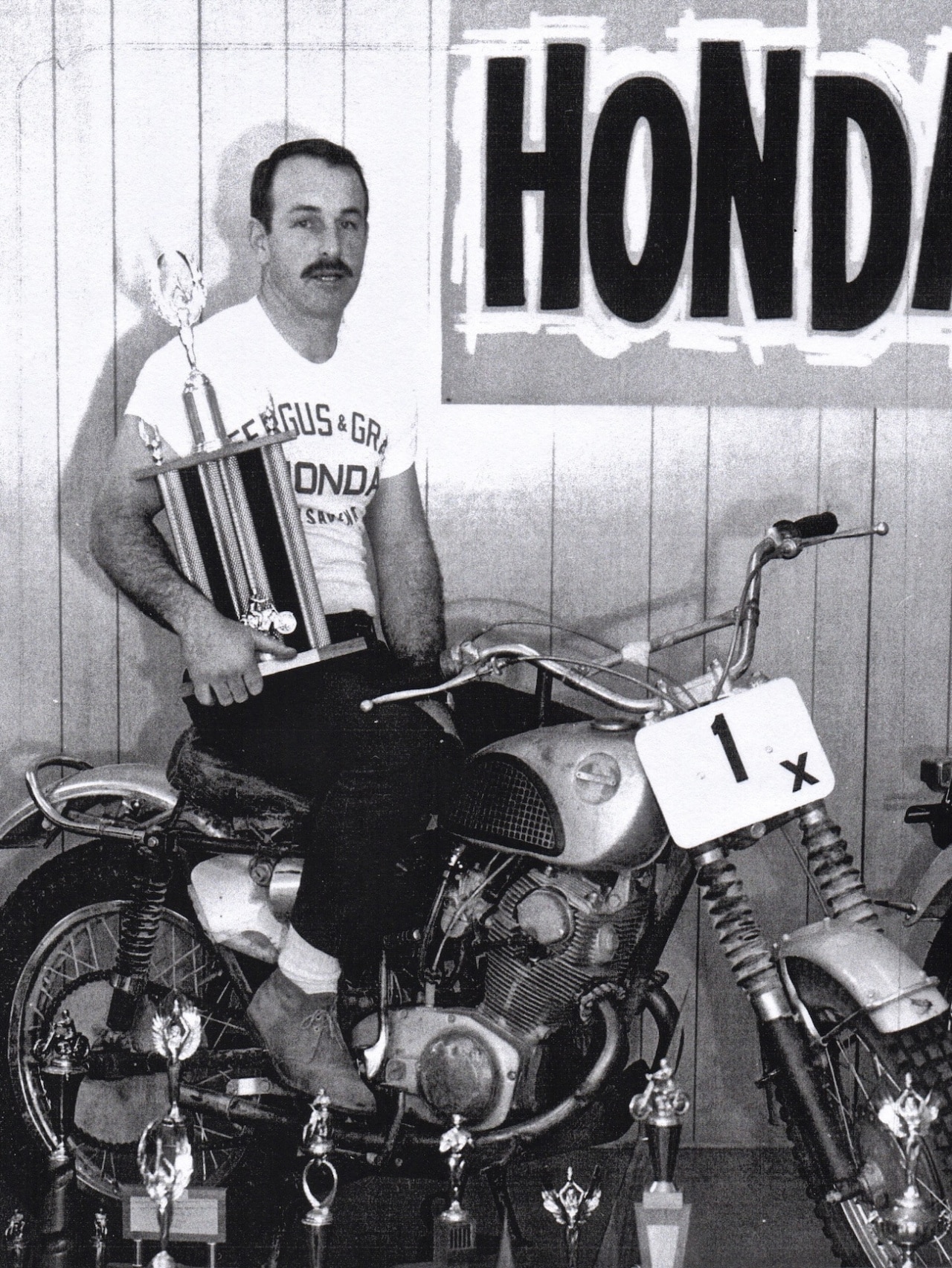

Neil Fergus was a desert racing star and number 1 rider. He rose to fame on a four-stroke, overhead cam, four-speed Honda Scrambler 250cc twin. He was the man Yamaha picked to test the first DT-1.

Neil Fergus was a desert racing star and number 1 rider. He rose to fame on a four-stroke, overhead cam, four-speed Honda Scrambler 250cc twin. He was the man Yamaha picked to test the first DT-1.

Back at Yamaha USA, Jack Hoel and Dave Holeman began cobbling together a prototype of what they wanted. They took some Yamaha parts and lots of Montesa Texas Scorpion parts (remember, Yamaha had proven with its YA1, née DKW RT125, that it was more than willing to emulate whatever worked). When Holeman and Hoel finished the proof-of-concept motorcycle, they had the beginnings of the 1968 DT1. It didn’t run, and lots of the parts were just dummied up, but the Americans were ready to approach the factory back in Hamamatsu with their proposal.

In the spring of 1966, the Americans made a presentation at Yamaha Motor headquarters in Japan, explaining the need for such a model. After sending the sample model to Japan, the design and engineering work for what would become the DT-1 began in October 1966. For its part, Yamaha wasn’t even clear what a trail bike was. To find out, they flew six engineers from Japan to California. Some spoke English; some didn’t. But, none of them had the slightest idea what an off-road race was. The Japanese engineers had never seen a desert sled, a desert tortoise, a cheeseburger or had the slightest idea what a Montesa Texas Scorpion was. Holeman and Hoel packed them into a van and headed for the massive Check Chase Desert Race. In 1966, desert racing was in its wild and woolly days. There were mass starts of 1000 motorcycles, black leather riding pants, a fun-loving club atmosphere and an aura of craziness. It was into this mix of the American wild west that the six amazed Japanese engineers were thrown. The sponsoring club started the race by exploding a giant dummy dressed in a rival club’s uniform with seven sticks of dynamite. Amid the dust, noise, mayhem, smoke and comings and goings stood the six bewildered and befuddled Japanese engineers.

Holeman and Hoel didn’t have the slightest idea what was going to happen when the six engineers got back to Japan with their stories of the American desert and the welded-up Yamaha/Montesa motorcycle sculpture. But, Jack and Dave had a list of things that the bike had to have. It had to be powered by a 250cc engine and look like a motocross bike but be able to be ridden on public roads, as well as mountain trails. The two Americans penciled out a request that listed the tire size, tread pattern, suspension travel, wheelbase, seat height, ground clearance and everything that they wanted. It wasn’t easy communicating between the American test crew and the Japanese development team, because only one side knew what was needed to ride off-road. But, they worked well together, and 60 days after the six engineers returned home, a crate arrived at Yamaha’s U.S. headquarters from Japan. When Holeman and Hoel opened it up, there sat two Yamaha DT1s. From this point on, the testing started in earnest.

Yamaha got desert star Neil Fergus to do the test riding on the two prototypes. Week in and week out, Fergus and riding partner Gary Griffin destroyed the DT-1s. Shocks faded, swingarms bent, frames broke and steering stems split down the middle. Hoel was kept busy sending detailed test reports, drawings, photos and components back to Japan, and the Japanese were steadily replacing parts so that Fergus could break them again. Finally, the prototype DT1 was done, and it was a happy day when the test unit was put in a crate and shipped to Japan to be duplicated. Imagine the test team’s surprise when a couple of days later the first pre-production models arrived on the American loading docks. How could Japan have turned the prototype into a production bike so quickly? They hadn’t. The Japanese were so committed to the project that they hadn’t waited for the Americans to finish testing the prototype. Instead, they took the reports, photos, drawings and memos that Jack Hoel had been sending them and set up a production line. The Fergus prototype was a much better motorcycle than the Japanese production model, but the die was cast—and the Yamaha DT1 was built.

AND HISTORY WAS MADE

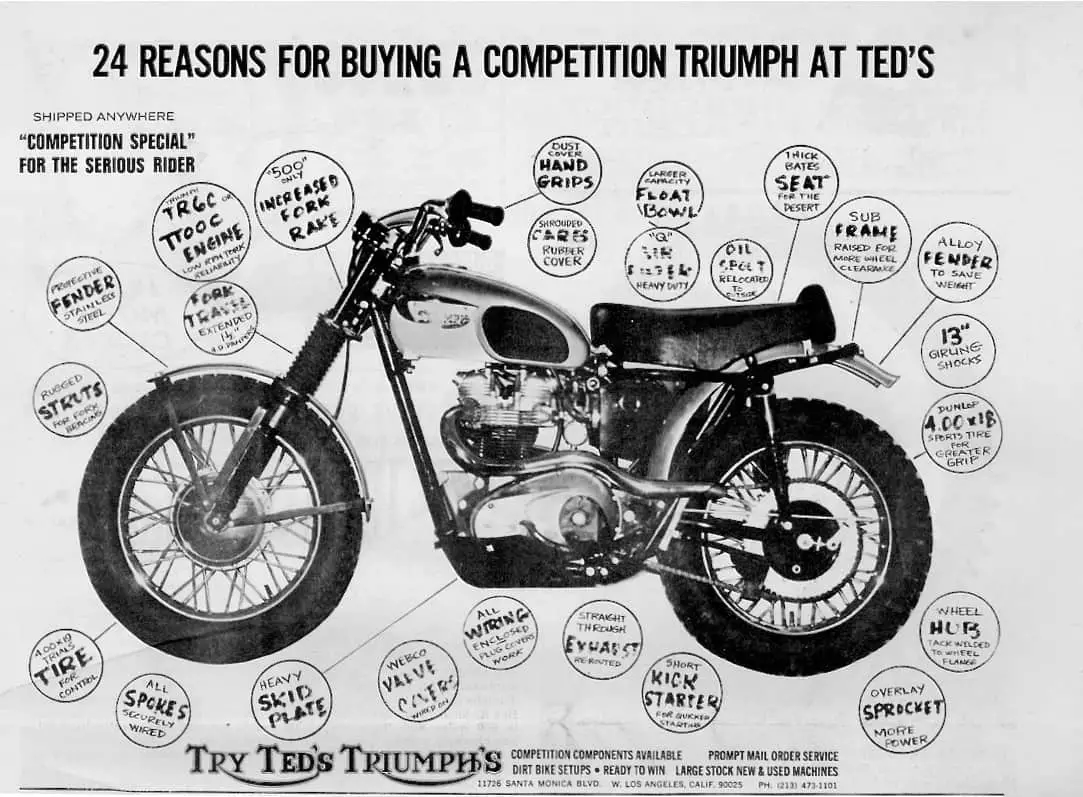

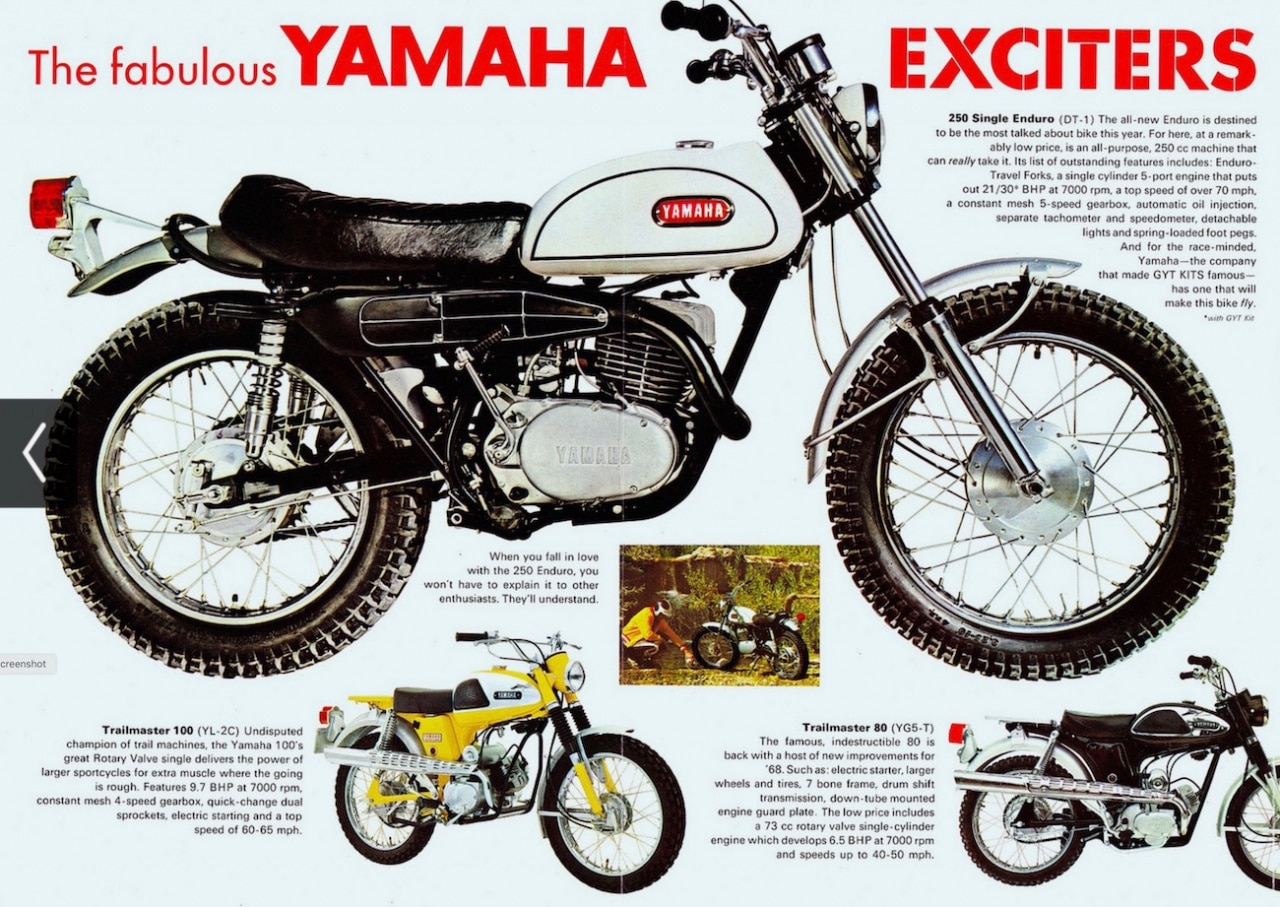

The first 1968 Yamaha DT-1 ad.

The first 1968 Yamaha DT-1 ad.

The 1966 Montesa Texas Scorpion helped the Japanese discover dirt bikes. Today, Montesa is owned by Honda.

The 1966 Montesa Texas Scorpion helped the Japanese discover dirt bikes. Today, Montesa is owned by Honda.

That is how the DT1 was born. In the winter of 1967, before the 1968 Yamaha DT1 was to be released to the public, Yamaha had to determine how many Yamaha DT1s should be produced for 1968. At that time, Yamaha only sold 4000 units a year in the USA. But, the enthusiasm, not just for the new bike but a new type of motorcycle (soon to be known as a “dirt bike”), inspired Yamaha to set the 1968 sales target at 12,000 units. Ambitious? Yes. Overly ambitious? No. The first batch of 8000 Yamaha DT1s that landed in America in March of 1968 sold out immediately. No European-built off-road motorcycle had ever seen the kind of phenomenal unit sales achieved by the original DT1. Production went into overdrive, and every DT-1 that rolled down the assembly line was headed for America.

The DT1 had been developed as an export-market model only, and no one at Yamaha thought that the Japanese market would have the slightest interest in an American dirt bike. They were wrong, but the domestic consumers had to wait while the American demand was met.

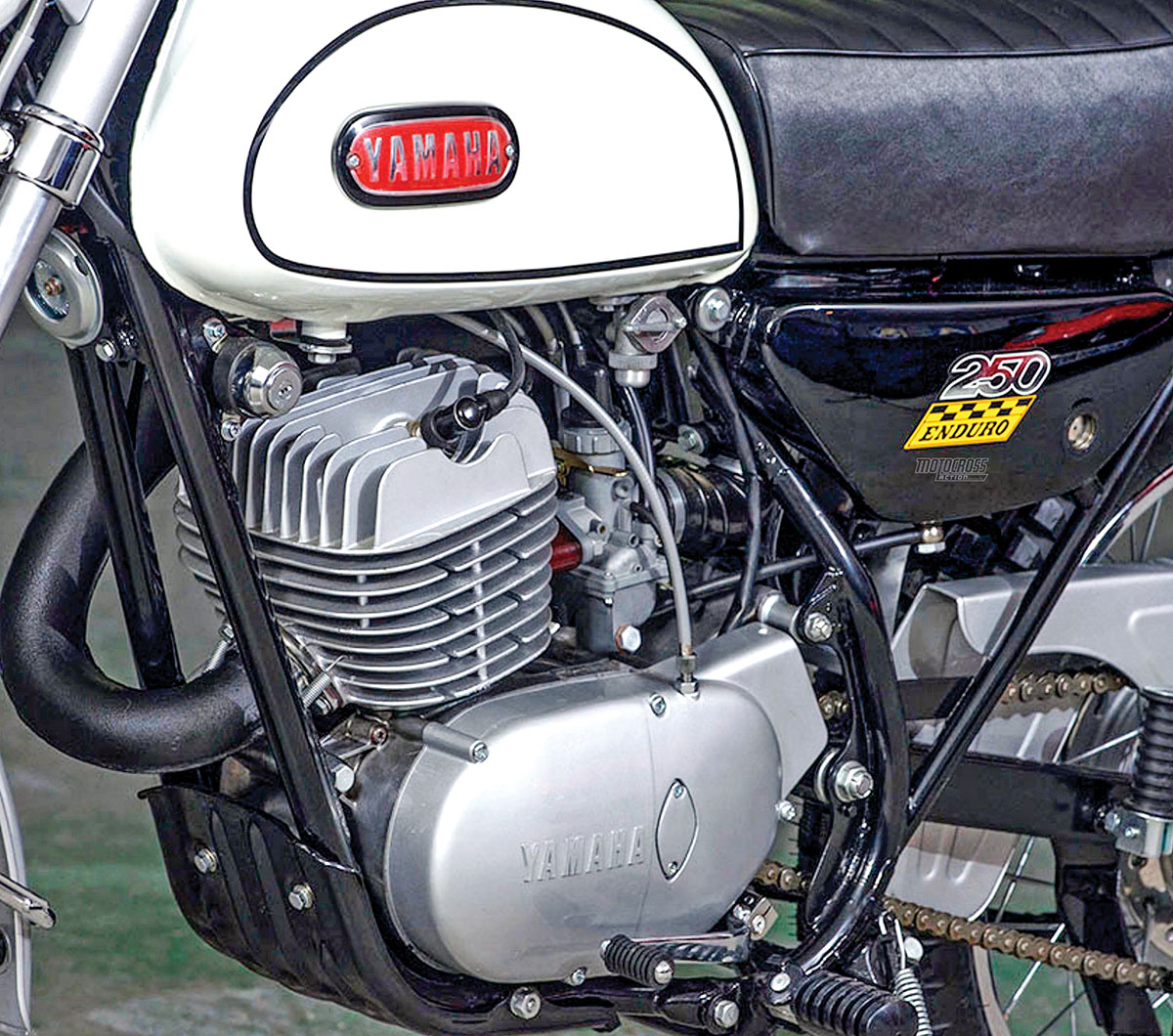

The bike wasn’t a radically advanced machine. In most ways, the Montesa Texas Scorpion was a far superior bike, with more horsepower, longer-travel suspension, less weight and great brakes. But even if the Yamaha DT1 did not plow new technological ground, it did supply the American public with an affordable ($700), reliable, 18.5-horsepower, 250cc, accessible off-road motorcycle that worked well. From that day on, the Japanese were here to stay in the world of off-road riding.

And perhaps because the Japanese hadn’t waited for the Neil Fergus test unit to be sent over, the DT1 wasn’t nearly as good as it could have been. Its frailties spawned the fledgling American off-road aftermarket business that included accessory forks (Ceriani and Betor), aftermarket shocks (Koni and Girling), aluminum rims (Akront and Boroni), plastic gas tanks, chromoly handlebars, hop-up pipes and plastic fenders. A whole new industry was launched with the introduction of the DT1. The early racing efforts, led by Keith Mashburn, Dennis Mahan, Neil Keen, Mike Patrick, Phil Bowers, and the Jones gang (Gary, Dewayne and Don) put the DT1 on the map in dirt track, desert and motocross. And, in an effort to fix the flaws of the rushed DT1, Yamaha pioneered the hop-up business with its GYT Kit (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) for the DT1. It consisted of a chromed cylinder, high-compression head, new piston, exhaust pipe and 30mm carb that added 10 horsepower. The DT1 250 was soon followed by the AT1 125, CT1 175, and RT1 360 (all with their own GYT kits).

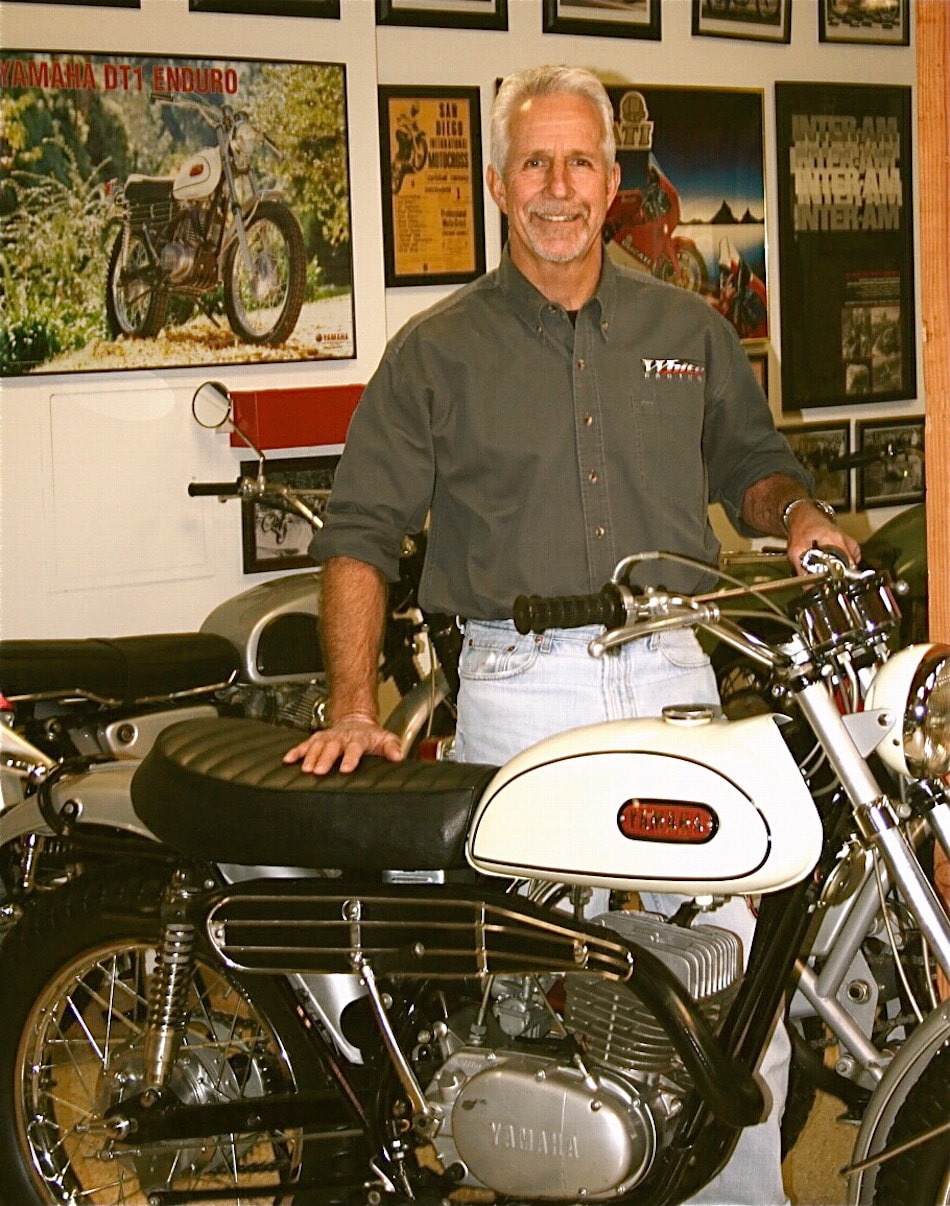

The late Tom White was an early adopter of the Yamaha DT-1, not only did he buy the first one that came to SoCal, but he made aftermarket parts for them. This is Tom with his spotless DT-1.

The late Tom White, founder of White Brothers Cycle Specialties, remembers what the DT1 did for the American motorcycle industry: “I first laid eyes on the Yamaha DT1 in December of 1967 at the annual Cycle World Motorcycle Show held in Anaheim. It was the star of the show. Nobody here had ever seen anything like it. I went to my dealer the next day and placed my order, and the bike finally arrived in April of 1968. Everybody was lining up to get this bike. It was a perfect combination for riding both on the street and off-road, and it had a very, very unique look and a very unique sound. It was a motorcycle that really changed the market here in America.”

From the DT1 came the current crop of off-road motorcycles and, unfortunately, out went the old-line European marques. The Montesa firm that built the Scorpion that Yamaha copied went out of business, and so did Bultaco, Greeves, BSA, Triumph, DKW, Norton, Matchless, Ossa, AJS and, for all practical U.S. motocross purposes, CZ, Husqvarna and Maico.

Torakusu Yamaha never saw a motorcycle, but if it hadn’t been for him, most of us may never have ridden one.

Comments are closed.